The most frequent haplotype in a samle of Armenians was seen against the background of HG1 Y chromosomes. It occurred in all Armenian groups, at frequencies ~5-14%. According to YHRD, the same haplotype defined over more loci (14 13 29 24 11 13 12 11,14) was also the most frequent one, occurring in 3% of Armenians (*). According to Whit Athey’s haplogroup predictor, this is suggestive of haplogroup R1b, also known as the Armenian modal haplotype.

A search for the haplotype in YHRD produced the following result: The geographical distribution of this haplotype is such that it is shared by Armenians and two other populations from the Caucasus. Moreover, it is lacking in most other populations from the Caucasus, as well as in the other populations from further east. On the other hand, it is more frequently found in Europe, where as we know, haplogroup R1b tends to have higher frequencies as well.The Armenian modal haplotype is also the modal R1b3 haplotype observed by Cinnioglu in Anatolia. According to him, apparently it entered Anatolia from Europe in Paleolithic times, and diffused again from Anatolia in the Late Upper Paleolithic.

An alternative explanation may be that the particular haplotype may have been associated with the movement of the Phrygians into Asia Minor. The Phrygians were an Indo-European people of the Balkans who settled in Asia Minor, and the Armenians were reputed to be descended from them. It would be interesting to thoroughly study the populations of modern Thrace, Anatolia, and Armenia, and to investigate whether a subgroup of R1b3 chromosomes linked by the Armenian modal haplotype may represent the signature of a back-migration into Asia of Balkan Indo-European peoples.

(*) Since this is an extended haplotype which includes some fast mutating markers, it is expected that it would occur at a lower frequency than the 6-locus haplotype reported by Weale et al.

XXX

Armenia has been little-studied genetically, even though it is situated in an important area with respect to theories of ancient Middle Eastern population expansion and the spread of Indo-European languages.

We screened 734 Armenian males for 11 biallelic and 6 microsatellite Y chromosome markers, segregated them according to paternal grandparental region of birth within or close to Armenia, and compared them with data from other population samples. We found significant regional stratification, on a level greater than that found in some comparisons between different ethno-national identities.

A diasporan Armenian subsample (collected in London) was not sufficient to describe this stratified haplotype distribution adequately, warning against the use of such samples as surrogates for the non-diasporan population in future studies.

The haplotype distribution and pattern of genetic distances suggest a high degree of genetic isolation in the mountainous southern and eastern regions, while in the northern, central and western regions there has been greater admixture with populations from neighbouring Middle Eastern countries.

Georgia, to the north of Armenia, also appears genetically more distinct, suggesting that in the past Trans-Caucasia may have acted as a genetic barrier. A Bayesian full-likelihood analysis of the Armenian sample yields a mean estimate for the start of population growth of 4.8 thousand years ago (95% credible interval: 2.0–11.1), consistent with the onset of Neolithic farming.

The more isolated southern and eastern regions have high frequencies of a microsatellite defined cluster within haplogroup 1 that is centred on a modal haplotype one step removed from the Atlantic Modal Haplotype, the centre of a cluster found at high frequencies in England, Friesland and Atlantic populations, and which may represent a remnant paternal signal of a Paleolithic migration event.

XXX

Armenians have a strong and distinct ethnic and cultural identity that unites them as an ethno-national group. The present-day country (size approx. 30,000 km2, population approx. 3.7 million) is situated in southern Trans-Caucasia between the Black and Caspian Seas at the boundaries of the Middle East, Northern Asia and Central Asia, although many self-identified Armenians continue to live in neighbouring countries or did so until recently.

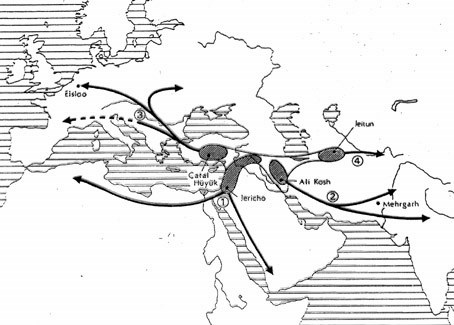

Armenia occupies an important location in the context of theories of early human population expansion and language development. Neolithic farming in Western Asia began between 8000 and 6000 BC in the Fertile Crescent some 500 km to the south, initiating a major but uneven population expansion that may have spread to other parts of Asia, including the Indian sub-continent and Europe (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994).

Archaeological evidence suggests that farming may have started in Armenia within the same period (Kushnareva 1990), with an increase in the local density of settlements occurring primarily in the Early Bronze Age (Kuro-Araxian culture) c. 3500–2500 BC (Badalyan 1986). It has been suggested that cranial similarities between modern Armenians and Armenian inhabitants of 1600–700 BC indicate a genetic continuity with ancient populations (Movsessyan and Kotchar 2000).

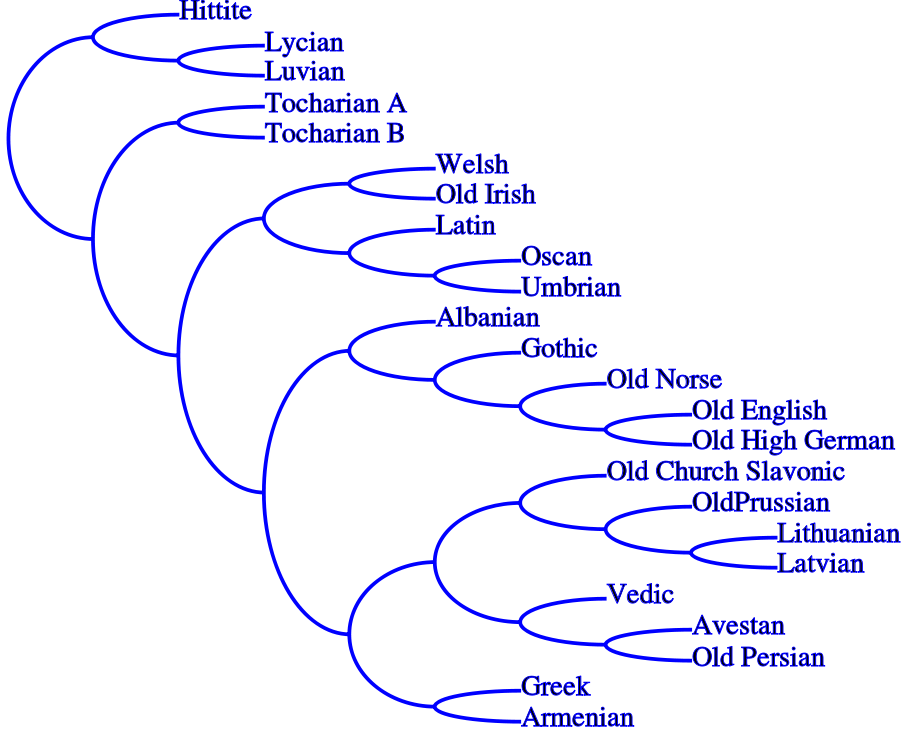

The Armenian language is an isolated branch, with uncertain affiliation, of Indo-European, the language group spoken today in most of Europe and east of Armenia throughout Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (Djahukian 1987). The origins of the hypothesised Proto-Indo-European language remain controversial.

While the first records of Indo-European languages appear in western Anatolia c. 1900–1700 BC (Hittite, Palaic, Luwian), the Proto-Indo-European homeland has been variously placed in the Ukraine (Mallory 1989), Anatolia (Renfrew 1987) and Armenia (Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1984) among others. The relative role of the Balkans (west of the Black Sea) and Trans-Caucasia (east of the Black Sea) as routes for early migrations that would have spread Indo-Euro-pean languages to the north or south remains uncertain (Mallory 1989).

The first evidence of Indo-European speaking people in the Armenian region dates to between 1300 and 700 BC. These people eventually replaced the non-Indo-European speaking Hurrians and later Urartians by 600 BC (Bournutian 1993; Hovannisian 1997; Redgate 1998). The Kingdom of Armenia reached its greatest extent by the first century BC, stretching southwest from present-day Armenia to the northeastern Mediterranean. In 301 AD Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity as the state religion.

For most of the period from the first century AD to the present day Armenia has been subject to the hegemony of more powerful neighbours, although a notable exception was the Armenian Bagratid dynasty of the ninth to eleventh centuries.

External powers that have ruled or exerted dominant political influence over Armenia include the Romans, Parthians (and later Persians), Byzantium, Seljuk Turks, Mongols (thirteenth to early fifteenth centuries), the Ottoman and Russian Empires, and most recently (until 1991) the Soviet Union. Forced and voluntary dispersions over the years have led to a large worldwide Armenian diaspora.

Georgia appears genetically isolated not only from Armenia but also from all other data sets in our comparison. It has two high-frequency haplotypes in hg2 (haplotype 78, 16.2%; and haplotype 134, 8.8%) found at high frequency in no other data set in this study. In contrast, Turkey has much higher genetic affinities with other data sets.

This supports the hypothesis that patterns of migration into or out of the Middle East occurred to a much larger extent via Anatolia and to the west of the Black Sea than via Georgia to the east of the Black Sea. Further resolution of these migration patterns will require more extensive sampling of populations to the north and east of Armenia.

Criticism

Against the Anatolian hypothesis stands the argument that PIE contains words for technologies that make their first appearance in the archaeological record in the Late Neolithic, in some cases bordering on the early Bronze Age, and that some of these words belong to the oldest layers of PIE.

The lexicon includes words relating to agriculture (dated to 7500 BCE), metallurgy (7500 BCE), stockbreeding (6500 BCE) the plow (4500 BCE), gold (4500 BCE), domesticated horses (4000–3500 BCE) and wheeled vehicles (4000–3400 BCE).

Horse breeding is thought to have originated with the Sredny Stog culture, semi-nomadic pastoralists living in the forest steppe zone in present-day Ukraine. Wheeled vehicles are thought to have originated with Funnelbeaker culture in what is now Poland, Belarus, and parts of Ukraine.

Most estimates from Indo-Europeanists date PIE between 4500 and 2500 BC, with the most probable date falling right around 3700 BC. It is unlikely that late PIE (even after the separation of the Anatolian branch) post-dates 2500 BC, since Proto-Indo-Iranian is usually dated to just before 2000 BC. On the other hand, it is not very likely that early PIE predates 4500 BC, because the reconstructed vocabulary strongly suggests a culture of the terminal phase of the Neolithic bordering on the early Bronze Age.

New evidence supports Anatolia hypothesis for origins of English

Language Continuity: Colin Renfrew. The Anatolian Hypothesis

Filed under: Uncategorized