An

In Sumerian mythology, Anu (also An; from Sumerian An, “sky, heaven”) was a sky-god, the god of heaven, lord of constellations, king of gods, spirits and demons, and dwelt in the highest heavenly regions. It was believed that he had the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and that he had created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the royal tiara. His attendant and minister of state was the god Ilabrat.

In Sumerian, the designation “An” was used interchangeably with “the heavens” so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted. The Akkadians inherited An as the god of heavens from the Sumerian as Anu-, and in Akkadian cuneiform, the DINGIR character may refer either to Anum or to the Akkadian word for god, ilu-, and consequently had two phonetic values an and il. Hittite cuneiform as adapted from the Old Assyrian kept the an value but abandoned il.

The Hurrians found the small state (or states) of Urkesh & Nawar, based on the two cities of the same name in northern Mesopotamia. Nawar seems to fall under the control of the Akkadian empire for a period, with the city serving as an administrative centre. The names of five of the kings of Urkesh and Nawar are known for this period, but there are certainly others whose names have been lost. Uniquely, the people of Urkesh use the term ‘endan’ to refer to the early kings.

Dingir

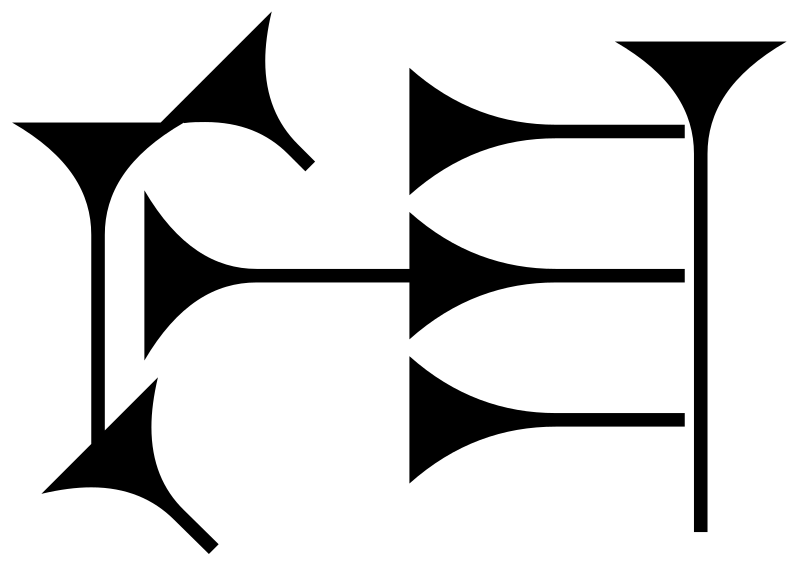

Dingir (usually transliterated diĝir) is a cuneiform sign, most commonly the determinative for “deity” although it has related meanings as well. As a determinative, it is not pronounced, and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript “D” as in e.g. DInanna. Generically, dingir can be translated as “god” or “goddess”.

The sign in Sumerian cuneiform (DIĜIR) by itself represents the Sumerian word an (“sky” or “heaven”), the ideogram for An or the word diĝir (“god”), the supreme deity of the Sumerian pantheon. In Assyrian cuneiform, it (AN, DIĜIR) could be either an ideogram for “deity” (ilum) or a syllabogram for an, or ìl-. In Hittite orthography, the syllabic value of the sign was again an.

The concept of “divinity” in Sumerian is closely associated with the heavens, as is evident from the fact that the cuneiform sign doubles as the ideogram for “sky”, and that its original shape is the picture of a star. The original association of “divinity” is thus with “bright” or “shining” hierophanies in the sky.

The Sumerian sign DIĜIRoriginated as a star-shaped ideogram indicating a god in general, or the Sumerian god An, the supreme father of the gods. Dingir also meant sky or heaven in contrast with ki which meant earth. Its emesal pronunciation was dimer.

NIN

The Sumerian word NIN (from the Akkadian pronunciation of the sign EREŠ) was used to denote a queen or a priestess, and is often translated as “lady”. Other translations include “queen”, “mistress”, “proprietress”, and “lord”.

Many goddesses are called NIN, such as NIN.GAL (“great lady”), É.NIN.GAL (“lady of the great temple”), EREŠ.KI.GAL, and NIN.TI. The compound form NIN.DINGIR (“divine lady” or “lady of [a] god”), from the Akkadian entu, denotes a priestess.

NIN originated as a ligature of the cuneiform glyphs of MUNUS and TÚG; the NIN sign was written as MUNUS.TÚG in archaic cuneiform, notably in the Codex Hammurabi. The syllable nin, on the other hand, was written as MUNUS.KA in Assyrian cuneiform. MUNUS.KU = NIN means “sister”.

Ninsun (NIN.SÚN) is the mother of Gilgamesh in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The other personage using NIN is the god Ninurta (NIN.URTA). The other major usage is for the Akkadian word eninna (nin as in e-nin-na, but also other variants). Eninna is the adverb “now”, but it can also be used as a conjunction, or as a segue-form (a transition form).

Filed under: Uncategorized