Sumer: An (sky god) – Enlil (north)/ Enki south)

Assyrians – Ashur (north)/ Babylonians – Marduk (south)

The rise to power

According to Babylonian myths, Marduk was not always the head god. At one time, all the gods were equal. But there was fighting amongst the gods. One in particular, Tiamat, was evil and hated the rest of the gods. Now Tiamut was very powerful and the other gods were afraid of her.

One of the other gods developed a plan. Ea, the water god, knew that Marduk could defeat Tiamut. So Ea went to Marduk and asked if he would be willing to fight Tiamut. Marduk thought about it. While he figured he could beat Tiamat, what if something went wrong? What if she captured him or even killed him? It had to be worth his efforts. So Marduk came back to Ea with a deal. He would fight Taimat if the rest of the gods would make him the head god forever.

Ea could not make that deal on his own. He had to get the rest of the gods to agree and he knew that some of them would oppose this idea, some because they were afraid of what would happen if Tiamat won and others because they didn’t want another god to be able to boss them around. But Ea was a very smart god. He had a plan.

Ea called all the gods together in an assembly. Ea provided the food, entertainment, and most of all the sweet, strong date wine so many of the gods loved. After allowing the rest of the gods to feast and drink lots of date wine, Ea put the idea to them. They agreed. So Ea went back to Marduk and let him know that if Marduk defeated Tiamat he would be the head god forever.

Marduk took a bow and arrows, his thunder club, his storm net, and his trademark – a lightning dagger – and set out to defeat Tiamat. The fighting that followed was stupendous. The battle raged for days with Marduk killing monster and demon left and right. Finally he got close enough to Tiamat that he was able to throw his net over her.

Trapped, Tiamat turned to destroy Marduk with a magical killing scream. Marduk was faster and shot an arrow down her throat killing her. He then cut her body in half and put half of it in the heavens guarded by the twinkling lights we call stars and made sure that the moon was there to watch over her. The rest he turned into the earth. Now that Tiamat was dead, Marduk was the leader of all the gods. In the first millennium, he was often referred to as Bel, the Akkadian word for “Lord.”

One of the best-known literary texts from ancient Mesopotamia describes Marduk’s dramatic rise to power: Assyriologists refer to this composition by its ancient title Enūma eliš, Akkadian for “When on high”. It is often called “The Babylonian Epic of Creation,” which is rather a misnomer as the main focus of the story is the elevation of Marduk to the head of the pantheon, for which the creation story is only a vehicle.

In this narrative, the god Marduk battles the goddess Tiamat, the deified ocean, often seen to represent a female principle, whereas Marduk stands for the male principle. Marduk is victorious, kills Tiamat, and creates the world from her body. In gratitude the other gods then bestow 50 names upon Marduk and select him to be their head. The number 50 is significant, because it was previously associated with the god Enlil, the former head of the pantheon, who was now replaced by Marduk.

This replacement of Enlil is already foreshadowed in the prologue to the famous Code of Hammurabi, a collection of “laws,” issued by Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE), the most famous king of the first dynasty of Babylon. In the prologue, Hammurabi mentions that the gods Anu and Enlil determined for Marduk to receive the “Enlil-ship” (stewardship) of all the people, and with this elevated him into the highest echelons of the Mesopotamian pantheon.

Another important literary text offers a different perspective on Marduk. The composition, one of the most intricate literary texts from ancient Mesopotamia, is often classified as “wisdom literature,” and ill-defined and problematic category of Akkadian literature. Assyriologists refer to this poem as Ludlul bēl nēmeqi “Let me praise the Lord of Wisdom,” after its first line, or alternatively as “The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer”.

The literary composition, which consists of four tablets of 120 lines each, begins with a 40-line hymnic praise of Marduk, in which his dual nature is described in complex poetic wording: Marduk is powerful, both good and evil, just as he can help humanity, he can also destroy people. The story then launches into a first-person narrative, in which the hero tells us of his continued misfortunes. It is this element that has often been compared to the Biblical story of Job.

In the end the sufferer is saved by Marduk and ends the poem by praising the god once more. In contrast to Enūma eliš the “Poem of the Righteous Sufferer” offers insights into personal relationships with Marduk. The highly complicated structure and unusual poetic language make this poem part of an elite and learned discourse.

It is interesting to note that Marduk had to get the consent of the assembly of gods to take on Tiamat. This is a reflection of how the people of Babylon governed themselves. The government of the gods was arranged in the same way as the government of the people. All the gods reported to Marduk just as all the nobles reported to the king. And Marduk had to listen to the assembly of gods just as the king had to listen to the assembly of people.

Marduk

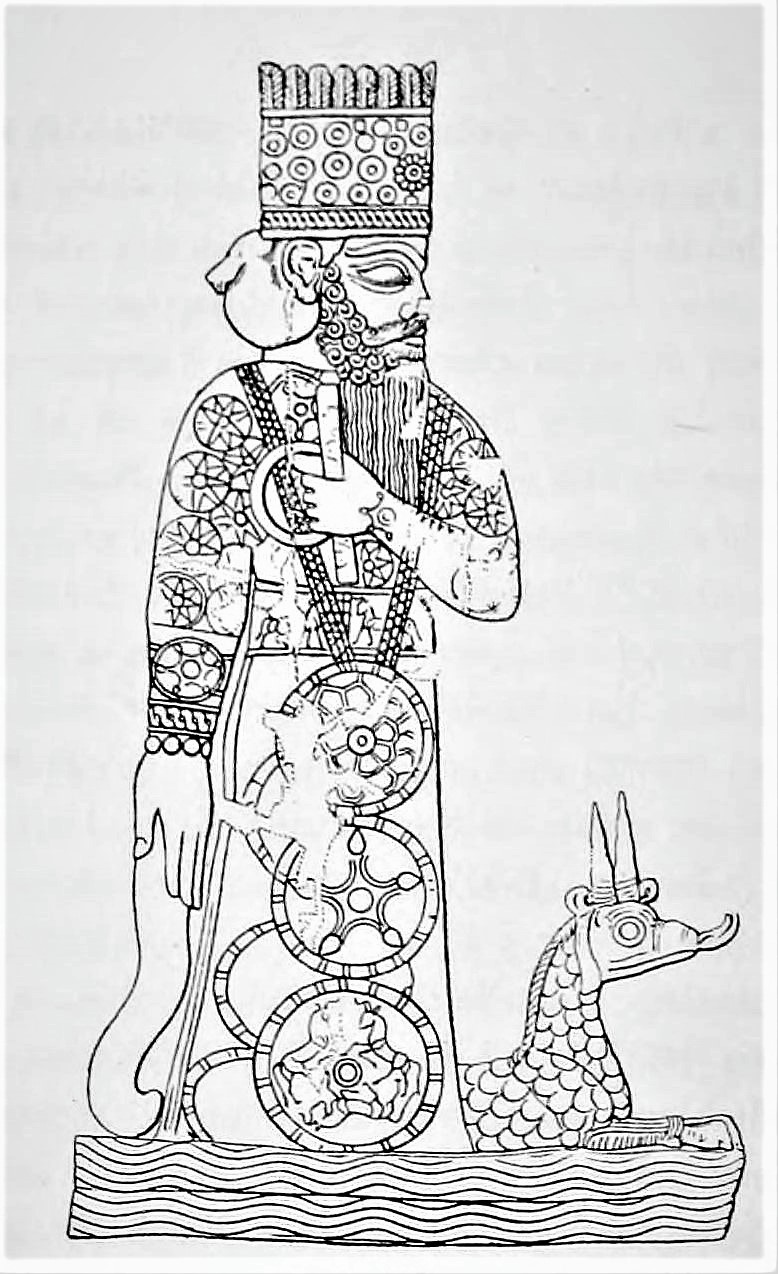

Marduk (Sumerian spelling in Akkadian: AMAR.UTU “solar calf”) was a late-generation god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. Marduk was depicted as a human, often with his symbol the snake-dragon which he had taken over from the god Tishpak. Another symbol that stood for Marduk was the spade.

According to The Encyclopedia of Religion, the name Marduk was probably pronounced Marutuk. “Marduk” is the Babylonian form of his name. The etymology of the name Marduk is conjectured as derived from amar-Utu (“bull calf of the sun god Utu”).

The origin of Marduk’s name may reflect an earlier genealogy, or have had cultural ties to the ancient city of Sippar (whose god was Utu, the sun god), dating back to the third millennium BC. Although the spelling of Marduk’s name (see below) appears to affiliate him with the sun god Utu, there is no evidence that he was ever considered to be the sun god’s son.

When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of Hammurabi (18th century BC), he slowly started to rise to the position of the head of the Babylonian pantheon, a position he fully acquired by the second half of the second millennium BC. In the city of Babylon, he resided in the temple Esagila. In the perfected system of astrology, the planet Jupiter was associated with Marduk by the Hammurabi period.

Marduk rose from an obscure deity in the third millennium BCE to become one of the most important gods and the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon in the first millennium. He was the patron god of the city of Babylon, where his temple tower, the ziggurat Etemenanki (“Temple (that is) the foundation of the heavens and the earth”) served as the model for the famous “tower of Babel.”

Marduk’s original character is obscure but he was later associated with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic. He was regarded as the son of Ea (Sumerian Enki) and Damkina and the heir of Anu. Whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to people of the time imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who in an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon.

There are particularly two gods – Ea and Enlil – whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk. In the case of Ea, the transfer proceeded pacifically and without effacing the older god. Marduk took over the identity of Asarluhi, the son of Ea and god of magic, so that Marduk was integrated in the pantheon of Eridu where both Ea and Asarluhi originally came from. Father Ea voluntarily recognized the superiority of the son and hands over to him the control of humanity.

Asalluhi is the son of Enki/Ea and a god of incantations and magic, sometimes merged with Marduk. The etymology and meaning of his name are unclear.The syncretism with Asalluhi is mentioned in a Sumerian literary letter to the goddess Ninsinna, in which Asalluhi is described as the “king of Babylon.”

This association of Marduk and Ea, while indicating primarily the passing of the supremacy once enjoyed by Eridu to Babylon as a religious and political centre, may also reflect an early dependence of Babylon upon Eridu, not necessarily of a political character but, in view of the spread of culture in the Euphrates valley from the south to the north, the recognition of Eridu as the older centre on the part of the younger one.

While the relationship between Ea and Marduk is marked by harmony and an amicable abdication on the part of the father in favour of his son, Marduk’s absorption of the power and prerogatives of Enlil of Nippur was at the expense of the latter’s prestige.

Babylon became independent in the early 19th century BC, and was initially a small city state, overshadowed by older and more powerful Mesopotamian states such as Isin, Larsa and Assyria.

However, after Hammurabi forged an empire in the 18th century BC, turning Babylon into the dominant state in the south, the cult of Marduk eclipsed that of Enlil; although Nippur and the cult of Enlil enjoyed a period of renaissance during the over four centuries of Kassite control in Babylonia (c. 1595 BC–1157 BC), the definite and permanent triumph of Marduk over Enlil became felt within Babylonia.

The only serious rival to Marduk after ca. 1750 BC was the god Aššur (Ashur) (who had been the supreme deity in the northern Mesopotamian state of Assyria since the 25th century BC) which was the dominant power in the region between the 14th to the late 7th century BC. In the south, Marduk reigned supreme. He is normally referred to as Bel “Lord”, also bel rabim “great lord”, bêl bêlim “lord of lords”, ab-kal ilâni bêl terêti “leader of the gods”, aklu bêl terieti “the wise, lord of oracles”, muballit mîte “reviver of the dead”, etc.

When Babylon became the principal city of southern Mesopotamia during the reign of Hammurabi in the 18th century BC, the patron deity of Babylon was elevated to the level of supreme god. In order to explain how Marduk seized power, Enûma Elish was written, which tells the story of Marduk’s birth, heroic deeds and becoming the ruler of the gods. This can be viewed as a form of Mesopotamian apologetics. Also included in this document are the fifty names of Marduk.

In Enûma Elish, a civil war between the gods was growing to a climactic battle. The Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call and was promised the position of head god.

To prepare for battle, he makes a bow, fletches arrows, grabs a mace, throws lightning before him, fills his body with flame, makes a net to encircle Tiamat within it, gathers the four winds so that no part of her could escape, creates seven nasty new winds such as the whirlwind and tornado, and raises up his mightiest weapon, the rain-flood. Then he sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths. In his lips he holds a spell and in one hand he grasps a herb to counter poison.

First, he challenges the leader of the Anunnaki gods, the dragon of the primordial sea Tiamat, to single combat and defeats her by trapping her with his net, blowing her up with his winds, and piercing her belly with an arrow. Then, he proceeds to defeat Kingu, who Tiamat put in charge of the army and wore the Tablets of Destiny on his breast, and “wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his” and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

After six generations of gods, in the Babylonian “Enuma Elish”, in the seventh generation, (Akkadian “shapattu” or sabath), the younger Igigi gods, the sons and daughters of Enlil and Ninlil, go on strike and refuse their duties of keeping the creation working.

Abzu, the god of fresh water, co-creator of the cosmos, threatens to destroy the world with his waters, and the Gods gather in terror. Enki promises to help and puts Abzu to sleep, confining him in irrigation canals and places him in the Kur, beneath his city of Eridu.

But the universe is still threatened, as Tiamat, angry at the imprisonment of Abzu and at the prompting of her son and vizier Kingu, decides to take back the creation herself. The gods gather again in terror and turn to Enki for help, but Enki who harnessed Abzu, Tiamat’s consort, for irrigation refuses to get involved.

The gods then seek help elsewhere, and the patriarchal Enlil, their father, God of Nippur, promises to solve the problem if they make him King of the Gods. In the Babylonian tale, Enlil’s role is taken by Marduk, Enki’s son, and in the Assyrian version it is Asshur.

After dispatching Tiamat with the “arrows of his winds” down her throat and constructing the heavens with the arch of her ribs, Enlil places her tail in the sky as the Milky Way, and her crying eyes become the source of the Tigris and Euphrates.

Samuel Noah Kramer believes that behind this myth of Enki’s confinement of Abzu lies an older one of the struggle between Enki and the Dragon Kur (the underworld).

But there is still the problem of “who will keep the cosmos working”. Enki, who might have otherwise come to their aid, is lying in a deep sleep and fails to hear their cries. His mother Nammu (creatrix also of Abzu and Tiamat) “brings the tears of the gods” before Enki and says: “Oh my son, arise from thy bed, from thy (slumber), work what is wise. Fashion servants for the Gods, may they produce their bread.”

Enki then advises that they create a servant of the gods, humankind, out of clay and blood. Against Enki’s wish the Gods decide to slay Kingu, and Enki finally consents to use Kingu’s blood to make the first human, with whom Enki always later has a close relationship, the first of the seven sages, seven wise men or “Abgallu” (Ab = water, Gal = great, Lu = Man), also known as Adapa. Enki assembles a team of divinities to help him, creating a host of “good and princely fashioners”.

He tells his mother “Oh my mother, the creature whose name thou has uttered, it exists. Bind upon it the will of the Gods; Mix the heart of clay that is over the Abyss, The good and princely fashioners will thicken the clay. Thou, do thou bring the limbs into existence; Ninmah (the Earth-mother goddess (Ninhursag, his wife and consort) will work above thee. Ninti (goddess of birth) will stand by thy fashioning; Oh my mother, decree thou its (the new born’s) fate.

Adapa, the first man fashioned, later goes and acts as the advisor to the King of Eridu, when in the Sumerian Kinglist, the “Me” of “kingship descends on Eridu”. Babylonian texts talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, “the holy city, the dwelling of their [the other gods] delight”.

The Atrahasis-Epos has it that Enlil requested from Nammu the creation of humans. And Nammu told him that with the help of Enki (her son) she can create humans in the image of gods.

Sarpanit

His consort was the goddess Sarpanit. Her name means “the shining one”, and she is sometimes associated with the planet Venus. By a play on words her name was interpreted as zēr-bānītu, or “creatress of seed”, and is thereby associated with the goddess Aruru, who, according to Babylonian myth, created mankind.

Her marriage with Marduk was celebrated annually at New Year in Babylon. She was worshipped via the rising moon, and was often depicted as being pregnant. She is also known as Erua. She may be the same as Gamsu, Ishtar, and/or Beltis.

Nabu

Nabu was originally a West Semitic god of wisdom from Ebla. His cult was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites after 2000 BCE. He Nabu was assimilated into Marduk’s cult, where he became known as Marduk’s minister, Ea’s grandson and Marduk’s son with Sarpanitum, and co-regent of the Mesopotamian pantheon. He is the Assyrian and Babylonian god of wisdom and writing. His consorts were Tashmetum and Nissaba.

Due to his role as Marduk’s minister and scribe, Nabu became the god of wisdom and writing, (including all works of science, religion and magic) taking over the role from the Sumerian goddess Nisaba. He was also worshipped as a god of fertility, a god of water, and a god of vegetation. He was also the keeper of the Tablets of Destiny, which recorded the fate of mankind and allowed him to increase or diminish the length of human life. He rides on a winged dragon known as Sirrush which originally belonged to his father Marduk.

His symbols are the clay tablet and stylus. In Babylonian astrology, Nabu was identified with the planet Mercury. As the god of wisdom and writing, Nabu was identified by the Greeks with Hermes, by the Romans with Mercury, and by the Egyptians with Thoth.

Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian: Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern city on the east bank of the Euphrates river, located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah in Iraq’s Babil Governorate, some 60 km north of Babylon and 30 km southwest of Baghdad. As was often the case in Mesopotamia, it was part of a pair of cities, separated by a river. Sippar was on the east side of the Euphrates, while its sister city, Sippar-Amnanum (modern Tell ed-Der), was on the west.

Despite the fact that thousands of cuneiform clay tablets have been recovered at the site, relatively little is known about the history of Sippar, which has been suggested as the location of the Biblical Sepharvaim in the Old Testament, i.e., “the two Sipparas,” or “the two booktowns”, which alludes to the two parts of the city in its dual form. The Sippara on the east bank of the Euphrates is now called Abu-Habba; that on the other bank was Akkad, the old capital of Sargon I, where he established a great library.

The chief deity of Sippar-Amnanum was Annunitum (or Anunit), the daughter of Enlil and a warlike aspect of Istar favored by the Akkadians, while Sippar was the centre of the worship of the god Adramelech or Adar-malik, a form of sun god related to Moloch. The melech element means “King” in Hebrew (representing Semitic מלך m-l-k, a Semitic root meaning “king”). Moloch worship was practiced by the Canaanites, Phoenicians, and related cultures in North Africa and the Levant.

Like many pagan gods, Adramelech is considered a demon in some Judeo-Christian traditions. So he appears in Milton’s Paradise Lost, where Adramelech is a fallen angel, vanquished by Uriel and Raphael. According to Collin de Plancy’s book on demonology, Adramelech became the President of the Senate of the demons. He is also the Chancellor of Hell and supervisor of Satan’s wardrobe.

Adramelech is generally depicted with a human torso and head, and the limbs of a mule or peacock. A poet’s description of Adramelech can be found in Robert Silverberg’s short story “Basileus”. Adramelech is described as “The enemy of God, greater in ambition, guile and mischief than Satan. A fiend more curst — a deeper hypocrite”.

They also worshipped the lunar deity Anamelech, meaning “Anu is king.” In Christian demonology, Anamelech is an Assyrian goddess later claimed by Christian sources to be a demon worshipped alongside Adramelech, the sun god. She takes the form of a quail.

Sepharvaim was according to the Old Testament in 2 Kings 17:24; 18:34; 19:13; Isa. 37:13 taken by a king of Assyria, probably Sargon II. According to (II Kings 17:31) the cult was brought by the Sepharvite colonists into Samaria: “the Sepharvites burnt their children in the fire to Adrammelech and Anammelech, the gods of Sepharvaim”.

The recent discovery of cuneiform inscriptions at Tel el-Amarna in Egypt consisting of official despatches to Pharaoh Amenophis IV and his predecessor from their agents in Palestine leads some Egyptologists to conclude that in the century before the Exodus an active literary intercourse was carried on between these nations, and that the medium of the correspondence was the Babylonian language and script.

However, it has not been conclusively proven which Egyptian Pharaoh the Amarna Letters reference or that the Judean Exodus necessarily occurred after these letters. After the deportation of the Israelite tribes, at least some of the residents of this city were brought to Samaria to repopulate it with other Gentile settlers.

Filed under: Uncategorized