Cybele has a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük (in the Konya region) where the statue of a pregnant goddess seated on a lion throne was found in a granary.

The Lion Gate (detail) of Mycenae – two lionesses flank the central column.

Cybele (perhaps “Mountain Mother”) was an originally Anatolian mother goddess; she is Phrygia’s only known goddess, and was probably its state deity.

Samson and the lions, Saint Trophime Church Portal (12th century).

The Storting (Norwegian: Stortinget, “the great thing” or “the great council”) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo.

Unbelievable real images behind the constellations

The lion

The lion has been an icon for humanity for thousands of years, appearing in cultures across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Despite incidents of attacks on humans, lions have enjoyed a positive depiction in culture as strong and noble.

A common depiction is their representation as “king of the jungle” or “king of beasts”; hence, the lion has been a popular symbol of royalty and stateliness, as well as a symbol of bravery.

Representations of lions date back to the early Upper Paleolithic. The lioness-headed ivory carving from Vogelherd cave in the Swabian Alb in southwestern Germany, dubbed Löwenmensch (lion-human) in German.

The sculpture has been determined to be at least 32,000 years old from the Aurignacian culture, but it may date to as early as 40,000 years ago. The sculpture has been interpreted as anthropomorphic, giving human characteristics to an animal, but it may represent a deity.

Two lions were depicted mating in the Chamber of Felines in 15,000-year-old Paleolithic cave paintings in the Lascaux caves. Cave lions also are depicted in the Chauvet Cave in the Ardèche region of southern France, where lionesses are depicted hunting for the pride in much the same strategy as contemporary lions, discovered in 1994; this has been dated at 32,000 years of age, though it may be of similar or younger age to Lascaux.

Rrepresentations of lions are common in Sumerian art and was significant in Sumerian mythology. In ancient Mesopotamia (from Sumer up to Assyrian and Babylonian times) it was a prominent symbol, where it was strongly associated with kingship. The classic Babylonian lion motif, found as a statue, carved or painted on walls, is often referred to as the striding lion of Babylon. It is in Babylon that the biblical Daniel is said to have been delivered from the lion’s den.

There are lions at the entrances of cities and sacred sites. Lions have been widely used in sculpture and statuary to provide a sense of majesty and awe, especially on public buildings. This usage dates back to the origin of civilization.

There are lions at the entrances of cities and sacred sites from Mesopotamian cultures. Notable examples include the Lion Gate of ancient Mycenae in Greece that has two lionesses flanking a column that represents a deity, and the gates in the walls of the Hittite city of Hattusa (Hittite: Ḫa-at-tu-ša, read “Ḫattuša”, Turkish: Hattuşaş), the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age.

The “Lion of Menecrates” is a funerary statue of a crouching lion, found near the cenotaph of Menecrates. The lion is Work of a famous Corinthian sculptor of the Archaic Greece, end of the 7th century BC, and is found at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu.

Lions are known in many cultures as the king of animals, which can be traced to the classical book Physiologus. The lion is featured in several fables of the sixth century BC Greek storyteller Aesop. In his fables, the famed Greek story teller Aesop utilized the lion’s symbolism of power and strength in The Lion and the Mouse and Lion’s Share.

In Socrates’ model of the psyche (as described by Plato), the bestial, selfish nature of humanity is described metaphorically as a lion, the “leontomorphic principle”.

Lions have been extensively used in ancient Persia as sculptures and on the walls of palaces, in fire temples, tombs, on dishes and jewellery; especially during the Achaemenid Empire. The gates were adorned with lions. Evidences are found in Persepolis, Susa, Hyrcania, etc.

A lion-faced figurine is usually associated with the Mithraic mysteries. Without any known parallel in classical, Egyptian or middle-eastern art, what this figure is meant to represent is currently unknown. Some have interpreted it to be a representation of Ahriman, of the aforementioned gnostic Demiurge, or of some similar malevolent, tyrannical entity, but it has also been interpreted as some sort of time or season deity or even a more positive symbol of enlightenment and spiritual transcendence.

In gnostic traditions, the Demiurge is depicted as a lion-faced figure (“leontoeides”). The gnostic concept of the Demiurge is usually that of a malevolent, petty creator of the physical realm, a false deity responsible for human misery and the gross matter than traps the spiritual essence of the soul, and thus an “animal-like” nature.

As a lion-headed figure, the Demiurge is associated with devouring flames, destroying the souls of humans after they die, as well as with arrogance and callousness.

Several Biblical accounts document the presence of lions, and cultural perception of them in ancient Palestine. The best known Biblical account featuring lions comes from the Book of Daniel (chapter 6), where Daniel is thrown into a den of lions and miraculously survives.

A lesser known Biblical account features Samson who kills a lion with his bare hands, later sees bees nesting in its carcass, and poses a riddle based on this unusual incident to test the faithfulness of his fiancee (Judges 14).

The prophet Amos said (Amos, 3, 8): “The lion hath roared, who will not fear? the Lord GOD hath spoken, who can but prophesy?”, i.e., when the gift of prophecy comes upon a person, he has no choice but to speak out. In 1 Peter 5:8, the Devil is compared to a roaring lion “seeking someone to devour.”

In Christian tradition, Mark the Evangelist, the author of the second gospel is symbolized by a lion – a figure of courage and monarchy. It also represents Jesus’ Resurrection (because lions were believed to sleep with open eyes, a comparison with Christ in the tomb), and Christ as king.

Some Christian legends refer to Saint Mark as “Saint Mark The Lionhearted”. These probably false legends say that he was fed to the Lions and the animals refused to attack or eat him. Instead the Lions slept at his feet, while he petted them. When the Romans saw this, they released him, spooked by the sight.

The lion is the biblical emblem of the tribe of Judah and later the Kingdom of Judah. In the modern state of Israel, the lion remains the symbol of the capital city of Jerusalem, emblazoned on both the flag and coat of arms of the city.

It is contained within Jacob’s blessing to his fourth son in the penultimate chapter of the Book of Genesis, “Judah is a lion’s whelp; On prey, my son have you grown. He crouches, lies down like a lion, like the king of beasts—who dare rouse him?” (Genesis 49:9).

Unlike Christianity, in Judaism, The Lion has positive connotations. For instance, in every synagogue there is an ark with a depiction in which lions face each other like bookends with the torah in the middle, as if they were protecting it.

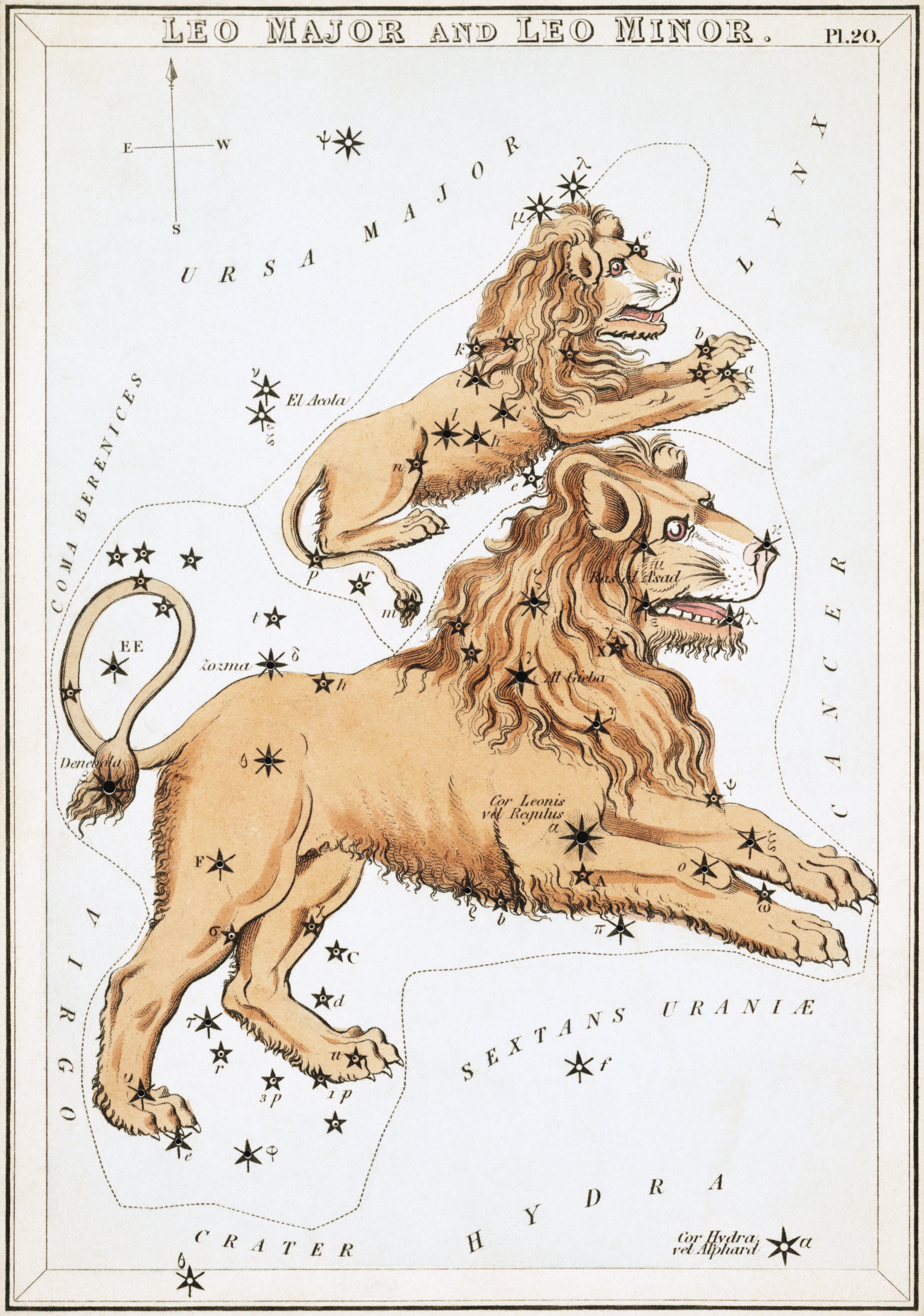

Leo

Leo is the fifth astrological sign of the zodiac, originating from the constellation of Leo. It spans the 120-150th degree of the Tropical zodiac, between 125.25 and 152.75 degree of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac, the Sun transits this area on average between July 23 and August 27 each year, and under the sidereal zodiac, the Sun currently transits this area from approximately August 16 to September 17.

Leo is one of the constellations of the zodiac, lying between Cancer to the west and Virgo to the east. Its name is Latin for lion, and to the ancient Greeks represented the Nemean Lion, the most notable lion of Ancient Greek mythology, that lived at Nemea and was killed by the mythical Greek hero Heracles (known to the ancient Romans as Hercules), who subsequently bore the pelt as an invulnerable magic cloak, barehanded as one of his twelve labors.

The Nemean Lion would take women as hostages to its lair in a cave, luring warriors from nearby towns to save the damsel in distress, to their misfortune. The Lion was impervious to any weaponry; thus, the warriors’ clubs, swords, and spears were rendered useless against it. Realizing that he must defeat the Lion with his bare hands, Hercules slipped into the Lion’s cave and engaged it at close quarters.

When the Lion pounced, Hercules caught it in midair, one hand grasping the Lion’s forelegs and the other its hind legs, and bent it backwards, breaking its back and freeing the trapped maidens. Zeus commemorated this labor by placing the Lion in the sky.

The Roman poet Ovid called it Herculeus Leo and Violentus Leo. Bacchi Sidus (star of Bacchus or star of Dionysus) was another of its titles, the god Bacchus always being identified with this animal. However, Manilius called it Jovis et Junonis Sidus (Star of Jupiter and Juno).

Leo is one of the most easily recognizable constellations due to its many bright stars and a distinctive shape that is reminiscent of the crouching lion it depicts. The lion’s mane and shoulders also form an asterism, a pattern of stars recognized in the Earth’s night sky or a part of an official constellation or it may be composed of stars from more than one constellation, known as “the Sickle,” which to modern observers may resemble a backwards “question mark.”

The glyph is generally thought to represent the tail of the lion. In ancient Dionysian mysteries it was considered to be a phallus. It can also symbolize the heat or creative energy of the Sun.

Leo is commonly represented as if the sickle-shaped asterism of stars is the back of the Lion’s head. The sickle is marked by six stars: Epsilon Leonis, Mu Leonis, Zeta Leonis, Gamma Leonis, Eta Leonis, and Alpha Leonis. The lion’s tail is marked by Beta Leonis (Denebola) and the rest of his body is delineated by Delta Leonis and Theta Leonis.

In astrology, Leo is considered to be a “masculine”, positive (extrovert) sign. It is also considered a fire sign and is one of four fixed signs ruled by the Sun. The Sun is the ruling planet of Leo and is exalted in Aries while Neptune is the ruling planet of Pisces and is exalted in Leo.

The Leo constellation is connected in almost every way to the sun. On entering the sign Leo, the Sun is said to exemplify cosmic splendor. The meaning attached to this seems to be that both the good and bad characteristics associated with Leo are perpetual.

In the zodiac, Leo is a fire sign and represents those born in the summer months. In ancient times, the constellation lined up almost perfectly with the summer solstice. Leo’s brightest star, Regulus, was often called the “Red Flame” and was thought to contribute to the heat of summer.

Through the ages, Leo has signified the coming of the high growing season and thus reflects the abundant generosity of life. In this aspect Leo is seen as the ordained provider, a role which many astrological lions would take on quite willingly.

It’s not entirely clear where the Egyptians believed the constellation to have come from directly, but the lion in Egypt is represented as an important animal to the livelihood of the Egyptians. Basically, the Egyptians relied on the Nile River to flood every year and nurture the land for the harvest.

During the summer months, the heat in the desert would be so great that the lions of the plains would move closer to the Nile to stay cool and have access to water. This coincided with the river’s yearly inundation – an event so crucial to the survival of the Egyptians that festivals were held to the gods regularly in hopes that the inundation would be good.

The war goddess Sekhmet typically was depicted as woman with a lioness head or, just as a lioness. The Egyptians held that a sacred lioness was responsible for the annual flooding of the Nile. Statues depicting lion heads can be found along building by the Nile.

Leo was one of the earliest recognized constellations, with archaeological evidence that the Mesopotamians had a similar constellation as early as 4000 BCE. The Persians called Leo Ser or Shir; the Turks, Artan; the Syrians, Aryo; the Jews, Arye; the Indians, Simha, all meaning “lion”.

Some mythologists believe that in Sumeria, Leo represented the monster Khumbaba, who was killed by Gilgamesh. In Babylonian astronomy, the constellation was called UR.GU.LA, the “Great Lion”; the bright star Regulus was known as “the star that stands at the Lion’s breast.” Regulus also had distinctly regal associations, as it was known as the King Star.

The Roman poet Ovid called it Herculeus Leo and Violentus Leo. Bacchi Sidus (star of Bacchus) was another of its titles, the god Bacchus always being identified with this animal. However, Manilius called it Jovis et Junonis Sidus (Star of Jupiter and Juno).

H.A. Rey has suggested an alternative way to connect the stars, which graphically shows a lion walking. Yet there is an even more fascinating approach to the lion constellation image then the one given in the diagram to the right.

In spring 2015 hobby astronomer evader from Germany discovered a stunning “realistic” lion image in the stars around the Leo constellation. For this purpose he used a computer generated skymap that shows more stars then are usually visible.

Regulus

Regulus (α Leo, α Leonis, Alpha Leonis) is the brightest star in the constellation Leo and one of the brightest stars in the night sky, lying approximately 79 light years from Earth. Regulus is a multiple star system composed of four stars that are organized into two pairs. Alpha (α) Leo, Regulus, is a triple star, 1.7, 8.5, and 13, flushed white and ultramarine in the Lion.

Rēgulus is Latin for ‘prince’ or ‘little king’. The Greek variant Basiliscus is also used. It is known as Qalb al-Asad, from the Arabic قلب الأسد, meaning ‘the heart of the lion’. This phrase is sometimes approximated as Kabelaced and translates into Latin as Cor Leōnis. It is known in Chinese as the Fourteenth Star of Xuanyuan, the Yellow Emperor. In Hindu astronomy, Regulus corresponds to the Nakshatra Magha (“the bountiful”).

Babylonians called it Sharru (“the King”), and it marked the 15th ecliptic constellation. In India it was known as Maghā (“the Mighty”), in Sogdiana Magh (“the Great”), in Persia Miyan (“the Centre”) and also as Venant, one of the four ‘royal stars’ of the Persian monarchy. It was one of the fifteen Behenian stars known to medieval astrologers, associated with granite, mugwort, and the kabbalistic symbol .

In MUL.APIN, Regulus is listed as LUGAL, meaning “the star that stands in the breast of the Lion: the King.” Lugal is the Sumerian cuneiform sign for leader from the two signs, LÚ.GAL (“man, big”), and was one of several Sumerian titles that a ruler of a city-state could bear (alongside en and ensi, the exact difference being a subject of debate).

The sign eventually became the predominant Sumerian term for a King in general. In the Sumerian language, lugal is used to mean an owner (e.g. of a boat or a field) or a head (of a unit such as a family). The cuneiform sign LUGAL serves as a determinative in cuneiform texts (Sumerian, Akkadian and Hittite), indicating that the following word is the name of a king. In Akkadian orthography, it may also be a syllabogram šàr, acrophonically based on the Akkadian for “king”, šarrum.

Regulus was so called by Polish astronomer Copernicus (1473-1543), as a diminutive of the earlier Rex, equivalent to the (Greek) Basiliskos (translated “Little King”) of the second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy.

This was from the belief that it ruled the affairs of the heavens, a belief current, till three centuries ago, from at least 3000 years before our era. Thus, as Sharru, the King, it marked the 15th ecliptic constellation of Babylonia; in India it was Magha, the Mighty; in Sogdiana (a Persian people), Magh, the Great, Miyan, the Centre; among the Turanian races, Masu, the Hero; and in Akkadia it was associated with the 5th antediluvian King-of-the-celestial-sphere, Amil-gal-ur, (Greek) Amegalaros. A Ninevite tablet has: “If the star of the great lion is gloomy the heart of the people will not rejoice.”

In Arabia it was Malikiyy, Kingly; in Greece, basiliskos aster (Little King star); in Rome, Basilica Stella; with Pliny (23-79 A.D.), Regia; in the revival of European astronomy, Rex; and with the 16th century Danish astronomer Tycho, Basiliscus.

So, too, it was the leader of the Four Royal Stars of the ancient Persian monarchy, the Four Guardians of Heaven. Dupuis, referring to this Persian character, said that the four stars marked the cardinal points, assigning Hastorang, as he termed it, to the North; Venant to the South; Tascheter to the East; and Satevis to the West: but did not identify these titles with the individual stars.

Flammarion does so, however, with Fomalhaut, Regulus, and Aldebaran for the first three respectively, so that we may consider Satevis as Antares. This same scheme appeared in India, although the authorities are not agreed as to these assignments and identifications; but, as the right ascensions are about six hours apart, they everywhere probably were used to mark the early equinoctial and solstitial colures, four great circles in the sky, or generally the four quarters of the heavens. At the time that these probably were first thought of, Regulus lay very near to the summer solstice, and so indicated the solstitial colure.

Early English astrologers made it a portent of glory, riches, and power to all born under its influence; Wyllyam Salysbury, of 1552, writing, but perhaps from Proclus:

“The Lyon’s herte is called of some men, the Royall Starre, for they that are borne under it, are thought to have a royall nativitie.” And this title, the Lion’s Heart, has been a popular one from early classical times, seen in the Kardia Leontos of Greece and the Cor Leonis of Rome, and adopted by the Arabians as Al Kalb al Asad, this degenerating into Kalbelasit, Kalbeleced, Kalbeleceid, Kalbol asadi, Calb-elez-id, Calb-elesit, Calb-alezet, and Kale Alased of various bygone lists.

The Persian astronomer Al Biruni (973-1048 A.D.) called it the Heart of the Royal Lion, which “rises when Suhail rises in Al Hijaz (in Saudi Arabia).

The 17th century German astronomer Bayer and others have quoted, as titles for Regulus, the strange Tyberone and Tuberoni Regia; but these are entirely wrong, and arose from a misconception of Pliny’s (23-79 A.D.) Stella Regia appellata Tuberoni in pectore Leonis, rendered “the star called by Tubero (Lucius Tubero, friend of Cicero) the Royal One in the Lion’s breast”. Holland’s translation reading: “The cleare and bright star, called the Star Royal, appearing in the breast of the signe Leo, Tubero mine author saith.”

Naturally sharing the character of its constellation as the Domicilium Solis, in Euphratean astronomy it was Gus-ba-ra, the Flame, or the Red Fire, of the House of the East; in Khorasmia, Achir, Possessing Luminous Rays; and throughout classical days the supposed cause of the summer’s heat, a reputation that it shared with the Dog-star. Horace (65-8 B.C.) expressed this in his Stella vesani Leonis.

It was of course prominent among the lunar-mansion stars, and chief in the 8th nakshatra (Hindu Moon Mansion) that bore its name, Magha, made up by all the components of the Sickle; and it marked the junction with the adjoining station Purva Phalguni; the Pitares, Fathers, being the regents of the asterism, which was figured as a House.

In Arabia, with gamma (γ Algieba), zeta (ζ Adhafera), and eta (η Al Jabhah) of the Sickle, it was the 8th manzil (Arabic Moon Mansion), Al Jabhah, the Forehead. In China, however, the 8th sieu (Chinese Moon Mansion) lay in Hydra; but the astronomers of that country referred to Regulus as the Great Star in Heen Yuen, a constellation called after the imperial family, comprising alpha (α Regulus), gamma (γ Algieba), epsilon (ε Ras Elased Australis), eta (η Al Jabhah), lambda (λ Alterf), zeta (ζ Adhafera), chi (χ), nu (ν), omicron (ο Subra), rho (ρ), and others adjacent and smaller reaching into the constellation Leo Minor. Individually it was Niau, the Bird, and so representative of the whole quadripartite zodiacal group.

Rix

Rí, or very commonly ríg (genitive), is an ancient Gaelic word meaning “king”. It is used in historical texts referring to the Irish and Scottish kings, and those of similar rank. While the Modern Irish word is exactly the same, in modern Scottish Gaelic it is rìgh, apparently derived from the genitive.

It also figures prominently as second element in Gothic names, Latinized as -rix, and often anglicized as -ric, e.g. in Theoderic (Þiuda-reiks). The use of the suffix extended into the Merovingian dynasty, with kings given names such as Childeric, and it survives in modern German names such as Ulrich, Dietrich.

Cognates include Gaulish Rix, Latin rex (genitive rēgis), Sanskrit raja, and German Reich English reign, Gothic reiks, modern German Reich and modern Dutch rijk etc., originally denoting heads of petty kingdoms and city states. It is believed to be ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European *hrēǵs, a vrddhi formation to the root *hreǵ- “to straighten, to order, to rule”.

The Sanskrit n-stem is secondary in the male title, apparently adapted from the female counterpart rājñī which also has an -n- suffix in related languages, compare Old Irish rígain and Latin regina. Rather common variants in Rajasthani, Marathi and Hindi, used for the same royal rank in parts of India include Rana, Rao, Raol, Rawal and Rawat.

Raja, the top title Thakore and many variations, compounds and derivations including either of these were used in and around South Asia by most Sinhalese Hindu, Muslim and some Buddhist, Jain and Sikh rulers, while Muslims also used Nawab or Sultan, and still is commonly used in India.

Raja means King in Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri is the Prince lineage of King’s generation in Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri title is aristocracy of the Kandiyan Kingdom in Sri Lanka. In Pakistan, Raja is still used by Muslim Rajput clans as hereditary titles. Raja is also used as a given name by Hindus and Sikhs. Most notably Raja is used in Hazara division of Pakistan for the descendants of Turk dynasty. These Rajas ruled that part of Pakistan for decades and they still possess huge land in Hazara division of Pakistan and actively participate in the politics of the region.

The Latin equivalent of Reich is not imperium, but rather regnum. Both terms translate to “rule, sovereignty, government”, usually of monarchs (kings or emperors), but also of gods, and of the Christian God. The German version of the Lord’s Prayer uses the words Dein Reich komme for “ἐλθέτω ἡ βασιλεία σου” (usually translated as “thy kingdom come” in English). Himmelreich is the German term for the concept of “kingdom of heaven”.

The German noun Reich is derived from Old High German rīhhi, which together with its cognates in Old English rīce Old Norse rîki (modern Scandinavian rike/rige) and Gothic reiki is from a Common Germanic *rīkijan. The English noun is extinct, but persists in composition, in bishop-ric.

The German adjective reich, on the other hand, has an exact cognate in English rich. Both the noun (*rīkijan) and the adjective (*rīkijaz) are derivations based on a Common Germanic *rīks “ruler, king”, reflected in Gothic as reiks, glossing ἄρχων “leader, ruler, chieftain”. It is probable that the Germanic word was not inherited from pre-Proto-Germanic, but rather loaned from Celtic (i.e. Gaulish rīx) at an early time.

Reiks is a Gothic title for a tribal ruler, often translated as “king”. In the Gothic Bible, it translates the Greek árchōn. It is presumably translated as basiliskos (“petty king”) in the Passio of Sabbas the Goth.

The Gothic Thervingi were divided into subdivisions of territory and people called kunja (singular kuni, cognate with English kin), by a reiks. In times of a common threat, one of the reiks would be selected as a kindins, or head of the Empire (translated as “judge”, Latin iudex, Greek δικαστής).

Herwig Wolfram suggested the position was different from the Roman definition of a rex (“king”), and is better described as that of a tribal chief. A reiks had a lower order of optimates or megistanes (μεγιστάνες, presumably translating mahteigs) beneath him, on whom he could call on for support.

The English term king is derived from the Anglo-Saxon cyning, which in turn is derived from the Common Germanic *kuningaz. The Common Germanic term was borrowed into Estonian and Finnish at an early time, surviving in these languages as kuningas. It is a derivation from the term *kunjom “kin” (Old English cynn) by the -inga- suffix. The literal meaning is that of a “scion of the [noble] kin”, or perhaps “son or descendant of one of noble birth”.

Aries

Kingu, also spelled Qingu, meaning “unskilled laborer,” was a god in Babylonian mythology, and — after the murder of his father Abzu — the consort of the goddess Tiamat, his mother, who wanted to establish him as ruler and leader of all gods before she was killed by Marduk.

Tiamat gave Kingu the 3 Tablets of Destiny, which he wore as a breastplate and which gave him great power. She placed him as the general of her army. However, like Tiamat, Kingu was eventually killed by Marduk.

Marduk mixed Kingu’s blood with earth and used the clay to mold the first human beings, while Tiamat’s body created the earth and the skies. Kingu then went to live in the underworld kingdom of Ereshkigal, along with the other deities who had sided with Tiamat.

The constellation of Aries was orignally named after unskilled labourers, Kingu or Qingu. The constellation was not considered important until the vernal equinox moved from Taurus to Aries. Inanna (Venus) was associated with the vernal equinox and hence Taurus. Thus Inanna or Ishtar became associated with Kingu, whose name changed to Dumuzi /Tammuz the shepherd king.

Dumuzi/Tammuz frees Inanna from the underworld and in return he and his sister both spend 6 months in the underworld in Inanna’s place. This symbolises the Vernal equinox when the Heavenly Bull was the first husband of Ereshkigal Goddess of the underworld and Inanna’s opposite. Tammuz replaces the bull of heaven as the sacrificial sign.

The MUL.APIN was a comprehensive table of the risings and settings of stars, which likely served as an agricultural calendar. In the description of the Babylonian zodiac given in the clay tablets known as the MUL.APIN, the constellation now known as Aries was the final station along the ecliptic. Modern-day Aries was known as LÚ.ḪUN.GÁ, “The Agrarian Worker” or “The Hired Man”.

Although likely compiled in the 12th or 11th century BC, the MUL.APIN reflects a tradition which marks the Pleiades as the vernal equinox, which was the case with some precision at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age.

The earliest identifiable reference to Aries as a distinct constellation comes from the boundary stones that date from 1350 to 1000 BC. On several boundary stones, a zodiacal ram figure is distinct from the other characters present. The shift in identification from the constellation as the Agrarian Worker to the Ram likely occurred in later Babylonian tradition because of its growing association with Dumuzi the Shepherd.

By the time the MUL.APIN was created—by 1000 BC—modern Aries was identified with both Dumuzi’s ram and a hired laborer. The exact timing of this shift is difficult to determine due to the lack of images of Aries or other ram figures.

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Aries was associated with the god Amon-Ra, who was depicted as a man with a ram’s head and represented fertility and creativity. Because it was the location of the vernal equinox, it was called the “Indicator of the Reborn Sun”.

During the times of the year when Aries was prominent, priests would process statues of Amon-Ra to temples, a practice that was modified by Persian astronomer centuries later. Aries acquired the title of “Lord of the Head” in Egypt, referring to its symbolic and mythological importance.

In ancient Greece the constellation of Aries is associated with the golden ram of Greek mythology that rescued Phrixos and Helle on orders from Hermes, taking him to the land of Colchis, and represented the Golden Fleece of the winged Ram. The ram was sacrificed to Poseidon who in ancient time ruled the underworld and the Golden Fleece was symbolic of that sacrifice. The Golden Fleece symbolised authority and kingship to the Greeks.

After arriving, Phrixos sacrificed the ram to Zeus and gave the Fleece to Aeëtes of Colchis, who rewarded him with an engagement to his daughter Chalciope. Aeëtes hung its skin in a sacred place where it became known as the Golden Fleece and was guarded by a dragon.

In the Old Testament Abram (noble father) and Sarai (princess) may represent Tammuz and Inanna who become (Abraham) father of many and (Sarah) mother of nations. Abraham’s son Isaac was too be used as a sacrificial lamb/ram until Abraham found the Ram presented by God.

Tammuz or Dumuzid means faithful son. In Sumerian tradition kings were married to Inanna as part of a ritual marriage of the land which is common of many cultures. Isaac’s wife Rebecca (tied up) representing Inanna in the underworld. The pure ram was the chosen sacrifice of the Hebrews and the Shofar (Ram’s horn) the sacred musical instrument of the temple.

Aegis

The aegis or aigis, as stated in the Iliad, is a goatskin shield or breastplate carried by Athena and Zeus, but its nature is uncertain. It had been interpreted as an animal skin or a shield, sometimes bearing the head of a Gorgon. At the center of Athena’s shield was the head of Medusa. There may be a connection with a deity named Aex or Aix, a nymph with a beautiful body and a horrible face. Aex was a daughter of Helios and a nurse of Zeus or alternatively a mistress of Zeus (Hyginus, Astronomica 2. 13).

The modern concept of doing something “under someone’s aegis” means doing something under the protection of a powerful, knowledgeable, or benevolent source. The word aegis is identified with protection by a strong force with its roots in Greek mythology and adopted by the Romans; there are parallels in Norse mythology and in Egyptian mythology as well, where the Greek word aegis is applied by extension.

Virgil imagines the Cyclopes in Hephaestus’ forge, who “busily burnished the aegis Athena wears in her angry moods—a fearsome thing with a surface of gold like scaly snake-skin, and he linked serpents and the Gorgon herself upon the goddess’s breast—a severed head rolling its eyes”, furnished with golden tassels and bearing the Gorgoneion (Medusa’s head) in the central boss.

Some of the Attic vase-painters retained an archaic tradition that the tassels had originally been serpents in their representations of the aegis. When the Olympian deities overtook the older deities of Greece and she was born of Metis (inside Zeus who had swallowed the goddess) and “re-born” through the head of Zeus fully clothed, Athena already wore her typical garments.

When the Olympian shakes the aegis, Mount Ida is wrapped in clouds, the thunder rolls and men are struck down with fear. “Aegis-bearing Zeus”, as he is in the Iliad, sometimes lends the fearsome aegis to Athena.

In the Iliad, when Zeus sends Apollo to revive the wounded Hector of Troy, Apollo holding the aegis, charges the Achaeans, pushing them back to their ships drawn up on the shore.

According to Edith Hamilton’s Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, the Aegis is the breastplate of Zeus, and was “awful to behold”. However, Zeus is normally portrayed in classical sculpture holding a thunderbolt or lightning, bearing neither a shield nor a breastplate.

The original meaning may have been #1, and Ζεὺς Αἰγίοχος = “Zeus who holds the aegis” may have originally meant “Sky/Heaven, who holds the thunderstorm”. The transition to the meaning “shield” or “goat-skin” may have come by folk-etymology among a people familiar with draping an animal skin over the left arm as a shield.

The aegis also appears in Ancient Egyptian mythology. The goddess Bast sometimes was depicted holding a ceremonial sistrum in one hand and an aegis in the other – the aegis usually resembling a collar or gorget embellished with a lioness head. Plato drew a parallel between Athene and the ancient Libyan and Egyptian goddess Neith, a war deity who also was depicted carrying a shield.

In Norse mythology, the dragon Fafnir (best known in the form of a dragon slain by Sigurðr) bears on his forehead the Ægis-helm (ON ægishjálmr), or Ægir’s helmet, or more specifically the “Helm of Terror”.

However, some versions would say that Alberich was the one holding a helm, named as the Tarnkappe, which has the power to make the user invisible. It may be an actual helmet or a magical sign with a rather poetic name.

Ægir is an Old Norse word meaning “terror” and the name of a destructive giant associated with the sea; ægis is the genitive (possessive) form of ægir and has no direct relation to Greek aigis.

Sacred marriage

In Mesopotamian Religion (Sumerian, Assyrian, Akkadian and Babylonian), Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the ocean, mating with Abzû (the god of fresh water) to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation, depicted as a woman who represents the beauty of the feminine, depicted as the glistening one. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.

Tiamat was the “shining” personification of salt water who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Apsu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is “Ummu-Hubur who formed all things”.

Tiamat was later known as Thalattē (as a variant of thalassa, the Greek word for “sea”) in the Hellenistic Babylonian writer Berossus’ first volume of universal history. It is thought that the name of Tiamat was dropped in secondary translations of the original religious texts (written in the East Semitic Akkadian language) because some Akkadian copyists of Enûma Elish substituted the ordinary word for “sea” for Tiamat, since the two names had become essentially the same due to association.

Thorkild Jacobsen and Walter Burkert both argue for a connection with the Akkadian word for sea, tâmtu, following an early form, ti’amtum. Burkert continues by making a linguistic connection to Tethys. Tiamat also has been claimed to be cognate with Northwest Semitic tehom (תהום) (the deeps, abyss), in the Book of Genesis 1:2.

It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos, the first in which Tiamat is a creator goddess, through a Hieros gamos or Hierogamy (“holy marriage”) between salt and fresh water, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second “Chaoskampf” Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” a Sumerian primeval goddess, corresponding to Tiamat in Babylonian mythology, was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Nammu is not well attested in Sumerian mythology. She may have been of greater importance prehistorically, before Enki took over most of her functions. An indication of her continued relevance may be found in the theophoric name of Ur-Nammu, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur.

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

According to the Neo-Sumerian mythological text Enki and Ninmah, Enki is the son of An and Nammu. Nammu is the goddess who “has given birth to the great gods”. It is she who has the idea of creating mankind, and she goes to wake up Enki, who is asleep in the Apsu, so that he may set the process going.

The cosmogenic myth common in Sumer was that of the hieros gamos, a sacred marriage where divine principles in the form of dualistic opposites came together as male and female to give birth to the cosmos.

This mingling of waters was known in Sumerian as Nammu, and was identified as the mother of Enki. It is thought that female deities are older than male ones in Mesopotamia and Tiamat may have begun as part of the cult of Nammu, a female principle of a watery creative force, with equally strong connections to the underworld, which predates the appearance of Ea-Enki.

In the epic Enki and Ninhursag, Enki, as lord of Ab or fresh water (also the Sumerian word for semen), is living with his wife in the paradise of Dilmun. Despite being a place where “the raven uttered no cries” and “the lion killed not, the wolf snatched not the lamb, unknown was the kid-killing dog, unknown was the grain devouring boar”, Dilmun had no water and Enki heard the cries of its Goddess, Ninsikil, and orders the sun-God Utu to bring fresh water from the Earth for Dilmun.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water'”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

Hieros gamos refers to a sexual ritual that plays out a marriage between a god and a goddess, especially when enacted in a symbolic ritual where human participants represent the deities. The notion of hieros gamos does not presuppose actual performance in ritual, but is also used in purely symbolic or mythological context, notably in alchemy and hence in Jungian psychology.

In Hinduism, Devadasi tradition (“servant of god”) is a religious tradition in which girls are “married” and dedicated to a deity (deva or devi) or to a Hindu temple and includes performance aspects such as those that take place in the temple as well as in the courtly and mujuvani [Telugu] or home context.

Originally, in addition to this and taking care of the temple and performing rituals, these women learned and practiced Sadir, Odissi and other classical Indian artistic traditions and enjoyed a high social status. Though traditionally, they carry out dances in the praise of lord, they also evolved into Sacred Marriage over time.

Sacred prostitution was common in the Ancient Near East as a form of “Sacred Marriage” or hieros gamos between the king of a Sumerian city-state and the High Priestess of Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and warfare.

Along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers there were many shrines and temples dedicated to Inanna. The temple of Eanna ((Sumerian: e-anna; Cuneiform: E.AN, meaning “house of heaven”) in Uruk was the greatest of these where sacred prostitution was a common practice.

In addition, according to Leick 1994 persons of asexual or hermaphroditic bodies and feminine men were particularly involved in the worship and ritual practices of Inanna’s temples. The deity of this fourth-millennium city was probably originally An. After its dedication to Inanna the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.

The temple housed Nadītu, priestesses of the goddess. The high priestess would choose for her bed a young man who represented the shepherd Dumuzid, consort of Inanna, in a hieros gamos or sacred marriage, celebrated during the annual Akitu (New Year) ceremony, at the spring Equinox or the annual Duku ceremony, just before Invisible Moon, with the autumn Equinox (Autumnal Zag-mu Festival).

According to Samuel Noah Kramer in The Sacred Marriage Rite, in late Sumerian history (end of the third millennium) kings established their legitimacy by taking the place of Dumuzi in the temple for one night on the tenth day of the New Year festival. A Sacred Marriage to Inanna may have conferred legitimacy on a number of rulers of Uruk. Gilgamesh is reputed to have refused marriage to Inanna, on the grounds of her misalliance with such kings as Lugalbanda and Damuzi.

In Greek mythology the classic instance is the wedding of Zeus and Hera celebrated at the Heraion of Samos, and doubtless its architectural and cultural predecessors. Some scholars would restrict the term to reenactments, but most accept its extension to real or simulated union in the promotion of fertility: such an ancient union of Demeter with Iasion, enacted in a thrice-plowed furrow, a primitive aspect of a sexually-active Demeter reported by Hesiod, is sited in Crete, origin of much early Greek myth.

In actual cultus, Walter Burkert found the Greek evidence “scanty and unclear”: “To what extent such a sacred marriage was not just a way of viewing nature, but an act expressed or hinted at in ritual is difficult to say” the best-known ritual example surviving in classical Greece is the hieros gamos enacted at the Anthesteria by the wife of the Archon basileus, the “Archon King” in Athens, originally therefore the queen of Athens, with Dionysus, presumably represented by his priest or the basileus himself, in the Boukoleion in the Agora.

The brief fertilizing mystical union engenders Dionysus, and doubled unions, of a god and of a mortal man on one night, result, through telegony, in the semi-divine nature of Greek heroes such as Theseus and Heracles among others.

Archon basileus was a Greek title, meaning “king magistrate”: the term is derived from the words archon “magistrate” and basileus “king” or “sovereign”. It is believed the archon basileus ’s wife, the basilinna, had to marry and have intercourse with the god Dionysos during a festival at the Boukoleion in Athens, to ensure the city’s safety.

It is uncertain how this was enacted. However, this was an important role for a woman who, according to Plutarch and Solon, would otherwise be confined to the house and be of little importance. During antiquity, women in Greece served as priestesses and presented oracles such as those issued at Delphi.

The white horse

The zodiac sign Leo creatively redrawn fits astonishingly to the chalk lines of the galloping White Horse of Uffington, one of the oldest chalk figures in England (there are dozens throughout the UK), according to the most recent tests dating from the late-bronze age, about 1200 BCE.

This result was obtained by using a technique which allowed soil sealed under the figures chalk in-fill to be compared to surrounding samples to determine how long it has been sealed from the atmosphere.

The discovery was done in the late winter of 2014, Leo high in the sky, spring approaching, by the Bavarian hobby astronomer and scientist Josef Krem from Germany, Munich, exploring the zodiac stars and other constellations cycling through the year upon similarity to Celtic coinage’s symbols, the horse being found very often.

Lengyel describes the horse on Celtic coinage meaningful as the dynamic symbol of human existence from procreation via life to death and resurrection (horse from dock in the east to muzzle showing west), ever repeating.

The French archaeologist Patrice Méniel has demonstrated based on examination of animal bones from many archaeological sites, a lack of hippophagy (horse eating) in ritual centres and burial sites in Gaul, although there is some evidence for hippophagy from earlier settlement sites in the same region.

The White Horse was possibly a place of seasonal celebrations more than 3000 years ago associated with the unknown Celtic zodiac sign of the horse. Due to the earth’s axial precession Regulus in the horse had its midnight culmination around winter solstice about 3400 years ago. Nowadays this position nearly is taken by the Winter Hexagon with the brightest star Sirius.

A very different creative connection of Leo’s stars reveals an almost realistic horse, obviously a mare. Around the first century an artist of the Celtic tribe Uneller at Contentin Peninsula, created a coin showing a low prancing female horse most naturalistic, some mystic symbols added.

This coin is treasured in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France (BnF), Cabinet des Medailles, there described officially as “Aigle sur une Jument” – Eagle on a Mare, but the riding bird also resembles much a raven, being the mediator between life and death closely connected to witchcraft.

Observing Leo in a moonless springtime night reveals a horse and a lion as well, after some contemplation. The lion is found with the Mesopotamian Inanna / Ishtar together with the owl, the horse belongs to Epona obviously conjoined with raven or eagle.

Horse worship

Horse worship is a spiritual practice with archaeological evidence of its existence during the Iron Age and, in some places, as far back as the Bronze Age. The horse was seen as divine, as a sacred animal associated with a particular deity, or as a totem animal impersonating the king or warrior.

While horse worship has been almost exclusively associated with Indo-European culture, by the Early Middle Ages it was also adopted by Turkic peoples. Horse worship still exists today in various regions of South Asia.

White horses (which are rarer than other colours of horse) have a special significance in the mythologies of cultures around the world. Though some mythologies are stories from earliest beliefs, other tales, though visionary or metaphorical, are found in liturgical sources as part of preserved, on-going traditions.

They are often associated with the sun chariot, with warrior-heroes, with fertility (in both mare and stallion manifestations), or with an end-of-time saviour, but other interpretations exist as well.

From earliest times white horses have been mythologized as possessing exceptional properties, transcending the normal world by having wings (e.g. Pegasus from Greek mythology), or having horns (the unicorn).

As part of its legendary dimension, the white horse in myth may be depicted with seven heads (Uchaishravas) or eight feet (Sleipnir), sometimes in groups or singly. There are also white horses which are divinatory, who prophesy or warn of danger.

As a rare or distinguished symbol, a white horse typically bears the hero- or god-figure in ceremonial roles or in triumph over negative forces. Herodotus reported that white horses were held as sacred animals in the Achaemenid court of Xerxes the Great (ruled 486-465 BC), while in other traditions the reverse happens when it was sacrificed to the gods.

In more than one tradition, the white horse carries patron saints or the world saviour in the end times (as in Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam), is associated with the sun or sun chariot (Ossetia) or bursts into existence in a fantastic way, emerging from the sea or a lightning bolt.

In Celtic mythology, Rhiannon, a mythic figure in the Mabinogion collection of legends, rides a “pale-white” horse. Because of this, she has been linked to the Romano-Celtic fertility horse goddess Epona and other instances of the veneration of horses in early Indo-European culture.

The Book of Zechariah twice mentions colored horses; in the first passage there are three colors (red, dappled, and white), and in the second there are four teams of horses (red, black, white, and finally dappled) pulling chariots. The second set of horses are referred to as “the four spirits of heaven, going out from standing in the presence of the Lord of the whole world.” They are described as patrolling the earth and keeping it peaceful.

In the New Testament, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse include one seated on a white horse and one on a pale horse – the “white” horse carried the rider Conquest (traditionally, Pestilence) while the “pale” horse carried the rider, Death.

However, the Greek word chloros, translated as pale, is often interpreted as sickly green or ashen grey rather than white. Later in the Book of Revelation, Christ rides a white horse out of heaven at the head of the armies of heaven to judge and make war upon the earth.

Two Christian saints are associated with white steeds: Saint James, as patron saint of Spain, rides a white horse in his martial aspect. Saint George, the patron saint of horsemen among other things, also rides a white horse. In Ossetia, the deity Uastyrdzhi, who embodied both the warrior and sun motifs often associated with white horses, became identified with the figure of St. George after the region adopted Christianity.

Islamic culture tells of a white horse named Al-Buraq who brought Muhammad to Jannah during the Night Journey. Al-Buraq was also said to transport Abraham (Ibrâhîm) when he visited his wife Hagar (Hājar) and son Ishmael (Ismâ`îl).

According to tradition, Abraham lived with one wife, Sarah in Syria, but the Buraq would transport him in the morning to Mecca to see his family there, and take him back to his Syrian wife in the evening. Al-Burāq (“lightning”) isn’t mentioned in the Quran but in some hadith (“tradition”).

Solar chariot

A “solar barge” (also “solar bark”, “solar barque”, “solar boat” and “sun boat”) is a mythological representation of the sun riding in a boat. The “Khufu ship”, a 43.6-meter-long vessel that was sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque.

This boat was rediscovered in May 1954 when archeologist Kamal el-Mallakh and inspector Zaki Nur found two ditches sealed off by about 40 blocks weighing 17 to 20 tonnes each. This boat was disassembled into 1,224 pieces and took over 10 years to reassemble. A nearby museum was built to house this boat. Other sun boats were found in Egypt dating to different pharonic dynasties.

Examples include the Neolithic petroglyphs, which (it has been speculated) show solar barges, the many early Egyptian goddesses who are related as sun deities and the later gods Ra and Horus depicted as riding in a solar barge (in Egyptian myths of the afterlife, Ra rides in an underground channel from west to east every night so that he can rise in the east the next morning), the Nebra sky disk, which is thought to show a depiction of a solar barge, and Nordic Bronze Age petroglyphs, including those found in Tanumshede often contains barges and sun crosses in different constellations.

Proto-Indo-European religion has a solar chariot, a mythological representation of the sun traversing the sky in a chariot. The concept is younger than that of the solar barge, and typically Indo-European, corresponding with the Indo-European expansion after the invention of the chariot in the 2nd millennium BC. The sun itself also was compared to a wheel, possibly in Proto-Indo-European, Greek hēliou kuklos, Sanskrit suryasya cakram, Anglo-Saxon sunnan hweogul (PIE *swelyosyo kukwelos).

In Norse mythology the chariot of the goddess Sól is drawn by Arvak and Alsvid. The Trundholm sun chariot dates to the Nordic Bronze Age, more than 2,500 years earlier than the Norse myth, but is often associated with it. Greek Helios riding in a chariot. Sol Invictus depicted riding a quadriga on the reverse of a Roman coin. Vedic Surya riding in a chariot drawn by seven horses.

In Germanic mythology the Sun is female and the Moon is male. The corresponding Old English name is Siȝel, continuing Proto-Germanic *Sôwilô or *Saewelô. The Old High German Sun goddess is Sunna.

In the Norse traditions, every day, Sól rode through the sky on her chariot, pulled by two horses named Arvak (Old Norse “early awake”) and Alsvid (Old Norse “very quick”). Sól also was called Sunna and Frau Sunne, from which are derived the words “sun” and “Sunday”. It is said that the gods fixed bellows underneath the two horses’ shoulders to help cool them off as they rode.

In Norse mythology, Odin’s eight-legged horse Sleipnir, “the best horse among gods and men”, is described as gray. Sleipnir is also the ancestor of another gray horse, Grani, who is owned by the hero Sigurd.

The antiquity of the myth that the Sun is pulled by horses is not definitely from the Nordic religion. Many other mythologies and religions contain a solar deity or carriage of the Sun pulled by horses. In Persian and Phrygian mythology, Mithras and Attis perform this task.

In Greek mythology, Apollo performs this task, although it was previously performed by Helios, occasionally referred to as Titan. The white winged horse Pegasus was the son of Poseidon and the gorgon Medusa. Poseidon was also the creator of horses, creating them out of the breaking waves when challenged to make a beautiful land animal.

In Slavic mythology, the war and fertility deity Svantovit owned an oracular white horse; the historian Saxo Grammaticus, in descriptions similar to those of Tacitus centuries before, says the priests divined the future by leading the white stallion between a series of fences and watching which leg, right or left, stepped first in each row.

One of the titles of God in Hungarian mythology was Hadúr, who, according to an unconfirmed source, wears pure copper and is a metalsmith. The Hungarian name for God was, and remains “Isten” and they followed Steppe Tengriism.

The ancient Magyars sacrificed white stallions to him before a battle. Additionally, there is a story (mentioned for example in Gesta Hungarorum) that conquering Magyars paid a white horse to Moravian chieftain Svatopluk I (in other forms of the story, it is instead the Bulgarian chieftain Salan) for a part of the land that later became the Kingdom of Hungary.

Actual historical background of the story is dubious because Svatopluk I was already dead when the first Hungarian tribes arrived. On the other hand, even Herodotus mentions in his Histories an Eastern custom, where sending a white horse as payment in exchange for land means casus belli. This custom roots in the ancient Eastern belief that stolen land would lose its fertility.

In Zoroastrianism, one of the three representations of Tishtrya, the hypostasis of the star Sirius, is that of a white stallion (the other two are as a young man, and as a bull).

The divinity takes this form during the last 10 days of every month of the Zoroastrian calendar, and also in a cosmogonical battle for control of rain. In this latter tale (Yasht 8.21-29), which appears in the Avesta’s hymns dedicated to Tishtrya, the divinity is opposed by Apaosha, the demon of drought, which appears as a black stallion.

White horses are also said to draw divine chariots, such as that of Aredvi Sura Anahita, who is the Avesta’s divinity of the waters. Representing various forms of water, her four horses are named “wind”, “rain”, “clouds” and “sleet” (Yasht 5.120).

Ashva is the Sanskrit word for a horse, one of the significant animals finding references in the Vedas as well as later Hindu scriptures. The corresponding Avestan term is aspa. The word is cognate to Latin equus, Greek ίππος (hippos), Germanic *ehwaz and Baltic *ašvā all from PIE *hek’wos.

There are repeated references to the horse in the Vedas (1500-500 BC). In particular the Rigveda has many equestrian scenes, often associated with chariots. The Ashvins are divine twins named for their horsemanship. The earliest undisputed finds of horse remains in South Asia are from the Swat culture (1500-500 BC).

White horses appear many times in Hindu mythology. In the Puranas, one of the precious objects that emerged while the devas and demons were churning the milky ocean was Uchaishravas (“long-ears” or “neighing aloud”), a snow-white seven-headed flying horse considered the best of horses, prototype and king of horses. A white horse of the sun is sometimes also mentioned as emerging separately.

Mahabharata mentions that Uchchaihshravas rose from the Samudra manthan (“churning of the milk ocean”) and Indra, the god-king of heaven, seized it and made it his vehicle (vahana). He rose from the ocean along with other treasures like goddess Lakshmi – the goddess of fortune, taken by god Vishnu as his consort and the amrita – the elixir of life.

Uchaishravas was at times ridden by Indra, the god-king of heaven and the lord of the devas, but is also recorded to be the horse of Bali, the king of demons. Indra is depicted as having a liking for white horses in several legends – he often steals the sacrificial horse to the consternation of all involved, such as in the story of Sagara, or the story of King Prithu.

Uchchaihshravas is also mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita (10.27, which is part of the Mahabharata), a discourse by god Krishna, an Avatar of Vishnu, to Arjuna. When Krishna declares to the source of the universe, he declares that among flying horses, he is Uchchaihshravas, who is born from the amrita.

The legend states that the first horse emerged from the depth of the ocean during the churning of the oceans. It was a horse with white color and had two wings. It was known by the name of Uchchaihshravas.

The legend continues that Indra, king of the devas, took away the mythical horse to his celestial abode, the svarga (heaven). Subsequently, Indra severed the wings of the horse and presented the same to the mankind. The wings were severed to ensure that the horse would remain on the earth (prithvi) and not fly back to Indra’s svarga.

The chariot of the solar deity Surya is drawn by seven horses, alternately described as all white, or as the colours of the rainbow. The charioteer of Surya is Aruna, who is also personified as the redness that accompanies the sunlight in dawn and dusk. The sun god is driven by a seven-horsed Chariot depicting the seven days of the week.

Hayagriva the Avatar of Vishnu is worshipped as the God of knowledge and wisdom, with a human body and a horse’s head, brilliant white in color, with white garments and seated on a white lotus. Kalki, the tenth incarnation of Vishnu and final world saviour, is predicted to appear riding a white horse, or in the form of a white horse.

Kanthaka was a white horse that was a royal servant and favourite horse of Prince Siddhartha, who later became Gautama Buddha. Siddhartha used Kanthaka in all major events described in Buddhist texts prior to his renunciation of the world. Following the departure of Siddhartha, it was said that Kanthaka died of a broken heart.

In ancient Roman religion, the October Horse (Latin Equus October) was an animal sacrifice to Mars carried out on October 15, coinciding with the end of the agricultural and military campaigning season. The rite took place during one of three horse-racing festivals held in honor of Mars, the others being the two Equirria on February 27 and March 14.

Two-horse chariot races (bigae) were held in the Campus Martius, the area of Rome named for Mars, after which the right-hand horse of the winning team was transfixed by a spear, then sacrificed. The horse’s head (caput) and tail (cauda) were cut off and used separately in the two subsequent parts of the ceremonies: two neighborhoods staged a fight for the right to display the head, and the freshly bloodied cauda was carried to the Regia for sprinkling the sacred hearth of Rome.

Ancient references to the Equus October are scattered over more than six centuries: the earliest is that of Timaeus (3rd century BC), who linked the sacrifice to the Trojan Horse and the Romans’ claim to Trojan descent, with the latest in the Calendar of Philocalus (354 AD), where it is noted as still occurring, even as Christianity was becoming the dominant religion of the Empire. Most scholars see an Etruscan influence on the early formation of the ceremonies.

The October Horse is the only instance of horse sacrifice in Roman religion; the Romans typically sacrificed animals that were a normal part of their diet. The unusual ritual of the October Horse has thus been analyzed at times in light of other Indo-European forms of horse sacrifice, such as the Vedic ashvamedha and the Irish ritual described by Giraldus Cambrensis, both of which have to do with kingship.

Although the ritual battle for possession of the head may preserve an element from the early period when Rome was ruled by kings, the October Horse’s collocation of agriculture and war is characteristic of the Republic. The sacred topography of the rite and the role of Mars in other equestrian festivals also suggest aspects of initiation and rebirth ritual. The complex or even contradictory aspects of the October Horse probably result from overlays of traditions accumulated over time.

Hayagriva

Horse cults and horse sacrifice was originally a feature of Eurasian nomad cultures. In India, Horse worship in the form of worship of Hayagriva (haya=horse, grīva=neck/face), a horse-headed avatar of the Lord Vishnu in Hinduism, dates back to 2000 BC, when the Indo-Aryan people started to migrate into the Indus valley.

Origins about the worship of Hayagriva have been researched, some of the early evidences dates back to 2,000 BCE, when Indo-Aryan people worshiped the horse for its speed, strength, intelligence. To this day, the worship of Hayagriva exists among the followers of Hinduism.

In Hinduism, Hayagriva is also considered an avatar of Vishnu. He is worshipped as the God of knowledge and wisdom, with a human body and a horse’s head, brilliant white in color, with white garments and seated on a white lotus. Symbolically, the story represents the triumph of pure knowledge, guided by the hand of God, over the demonic forces of passion and darkness.

He is also hailed as Hayasirsa (haya=horse, śirṣa=head). Hayagriva is referred to as the “Horse necked one”, Defender of faith”, the “Terrible executioner”, the “Excellent Horse”, and the “Aerial horse”. In several other sources he is a white horse who pulls the sun into the sky every morning, bringing light to darkness.

Hayagriva’s consort is Marichi (Marishi-Ten) and/or Lakshmi (possibly an avatar of Marichi or Kan’non), the goddess of the rising sun, more accurately the sun’s light which is the life force of all things, and which is seen as the female [in, yin] aspect of Hayagriva.

Marichi represents the essence of the power of creation of the cosmos, and is the in/yin half of Dainichi Nyôrai whereas Hayagriva represents the other yang/yô aspect that of the manifestation of the power of yin/in as action.

In other words, Hayagriva represents the manifestation of yin/in as the power and action of the cosmos manifested as action. This is the very definition of tantra, that of action.

In others such as the great epic Taraka-battle where the gods are fallen on and attacked by the danava’s [demons], Vishnu appears as a great ferocious warrior called Hayagriva when he comes to their aid.

There are many other references to Hayagriva throughout the Mahabharata. It is said that Vishnu comes from battle as a conqueror in the magnificent mystic form of the great and terrible Hayagriva.

Invariably, Hayagriva is depicted seated, most often with his right hand either blessing the supplicant or in the vyākhyā mudrā pose of teaching. The right hand also usually holds a akṣa-mālā (rosary), indicating his identification with meditative knowledge. His left holds a book, indicating his role as a teacher. His face is always serene and peaceful, if not smiling.

Unlike his Buddhist counterpart, there is no hint of a fearsome side in the Hindu description of this deity. Indeed, the two deities seem to be totally unrelated to one another.

Hayagriva is sometimes worshiped in a solitary pose of meditation, as in the Thiruvanthipuram temple. This form is known as Yoga-Hayagriva. However, he is most commonly worshipped along with his consort Lakshmi and is known as Lakshmi-Hayagriva. Hayagriva in this form is the presiding deity of Mysore’s Parakala Mutt, a significant Sri Vaishnavism monastic institution.

A legend has it that during the creation, the demons Madhu-Kaitabha stole the Vedas from Brahma, and Vishnu then took the Hayagriva form to recover them. The two bodies of Madhu and Kaitabha disintegrated into twelve pieces (two heads, two torsos, four arms and four legs). These are considered to represent the twelve seismic plates of the Earth. Yet another legend has it that during the creation, Vishnu compiled the Vedas in the Hayagrīva form.

Some consider Hayagriva to be one of the Dashavataras of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He along with Śrī Krishna, ShrīRama and Shri Narasimha is considered to be an important avatar of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

Hayagriva is one of the prominent deity in Vaishnava tradition. His blessings are sought when beginning study of both sacred and secular subjects. Special worship is conducted on the day of the full moon in August (Śravaṇa-Paurṇamī) (his avatāra-dina) and on Mahanavami, the ninth day of the Navaratri festival.

The divine twins

The Ashvins is or Ashwini Kumaras in Hindu mythology, are two Vedic gods, divine twin horsemen in the Rigveda, sons of Saranyu (daughter of Vishwakarma), a goddess of the clouds and wife of Surya in his form as Vivasvant. They symbolise the shining of sunrise and sunset, appearing in the sky before the dawn in a golden chariot, bringing treasures to men and averting misfortune and sickness.

They are the doctors of gods and are devas of Ayurvedic medicine. They are represented as humans with head of a horse. In the epic Mahabharata, King Pandu’s wife Madri is granted a son by each Ashvin and bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva who, along with the sons of Kunti, are known as the Pandavas.

They are also called Nasatya (dual nāsatyau “kind, helpful”) in the Rigveda; later, Nasatya is the name of one twin, while the other is called Dasra (“enlightened giving”). By popular etymology, the name nāsatya is often incorrectly analysed as na+asatya “not untrue”=”true”.

Various Indian holy books like Mahabharat, Puranas etc., relate that Ashwini Kumar brothers, the twins, who were RajVaidhya (Royal Physicians) to Devas during Vedic times, first prepared Chyawanprash formulation for Chyawan Rishi at his Ashram on Dhosi Hill near Narnaul, Haryana, India, hence the name Chyawanprash.

The Ashvins can be compared with the Dioscuri (the twins Castor and Pollux) of Greek and Roman mythology, to the divine twins Ašvieniai of the ancient Baltic religion, and the Germanic Alcis.

The Ashvins are mentioned 376 times in the Rigveda, with 57 hymns specifically dedicated to them. The Nasatya twins are invoked in a treaty between Suppiluliuma and Shattiwaza, kings of the Hittites and the Mitanni respectively.

Ashvini is the first nakshatra (lunar mansion) in Hindu astrology having a spread from 0°-0′-0″ to 13°-20′, corresponding to the head of Aries, including the stars β and γ Arietis.

The name aśvinī is used by Varahamihira (6th century). The older name of the asterism, found in the Atharvaveda (AVS 19.7; in the dual) and in Panini (4.3.36), was aśvayúj “harnessing horses”.

Ashvini is ruled by Ketu, the descending lunar node. In electional astrology, Asvini is classified as a Small constellation, meaning that it is believed to be advantageous to begin works of a precise or delicate nature while the moon is in Ashvini.

Asvini is ruled by the Ashvins, the heavenly twins who served as physicians to the gods. Personified, Asvini is considered to be the wife of the Asvini Kumaras. Ashvini is represented either by the head of a horse, or by honey and the bee hive.

Traditional Hindu given names are determined by which pada (quarter) of a nakshatra the moon was in at the time of birth. In the case of Ashvini, the given name would begin with the following syllables:

In Greek and Roman mythology, Castor and Pollux or Polydeuces were twin brothers, together known as the Dioskouri. Their mother was Leda, but Castor was the mortal son of Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, and Pollux the divine son of Zeus, who seduced Leda in the guise of a swan. Though accounts of their birth are varied, they are sometimes said to have been born from an egg, along with their twin sisters and half-sisters Helen of Troy and Clytemnestra.

In Latin the twins are also known as the Gemini or Castores. When Castor was killed, Pollux asked Zeus to let him share his own immortality with his twin to keep them together, and they were transformed into the constellation Gemini. The pair was regarded as the patrons of sailors, to whom they appeared as St. Elmo’s fire, and were also associated with horsemanship. They are sometimes called the Tyndaridae or Tyndarids, later seen as a reference to their father and stepfather Tyndareus.

Both Dioscuri were excellent horsemen and hunters who participated in the hunting of the Calydonian Boar and later joined the crew of Jason’s ship, the Argo. Castor and Pollux aspired to marry the Leucippides (“daughters of the white horse”), Phoebe and Hilaeira, whose father was a brother of Leucippus (“white horse”).

Both women were already betrothed to cousins of the Dioscuri, the twin brothers Lynceus and Idas of Thebes, sons of Tyndareus’s brother Aphareus. Castor and Pollux carried the women off to Sparta wherein each had a son; Phoebe bore Mnesileos to Pollux and Hilaeira bore Anogon to Castor. This began a family feud among the four sons of the brothers Tyndareus and Aphareus.

Castor and Pollux are consistently associated with horses in art and literature. They are widely depicted as helmeted horsemen carrying spears. The Pseudo-Oppian manuscript depicts the brothers hunting, both on horseback and on foot.

Horse sacrifice

Many Indo-European religious branches show evidence for horse sacrifice, and comparative mythology suggests that they derive from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) ritual. Some scholars, including Edgar Polomé, however, regard the reconstruction of a PIE ritual as unjustified due to the difference between the attested traditions.

Often horses are sacrificed in a funerary context, and interred with the deceased, a practice called horse burial. There is evidence but no explicit myths from the three branches of Indo-Europeans of a major horse sacrifice ritual based on a mythical union of Indo-European kingship and the horse. The Indian Aśvamedha is the clearest evidence preserved, but vestiges from Latin and Celtic traditions allow the reconstruction of a few common attributes.

The Gaulish personal name Epomeduos is from ek’wo-medhu- (“horse + mead”), while aśvamedha is either from ek’wo-mad-dho- (“horse + drunk”) or ek’wo-mey-dho- (“horse + strength”).

The reconstructed myth involves the coupling of a king with a divine mare which produced the divine twins. A related myth is that of a hero magically twinned with a horse foaled at the time of his birth (for example Cuchulainn, Pryderi), suggested to be fundamentally the same myth as that of the divine twin horsemen by the mytheme of a “mare-suckled” hero from Greek and medieval Serbian evidence, or mythical horses with human traits (Xanthos), suggesting totemic identity of the Indo-European hero or king with the horse.

The Indian Ashvamedha involves the sacrifice of a grey or white stallion and is connected with the elevation or inauguration of a member of the warrior caste. The ceremony took place in springtime and the stallion selected was one which excelled at the right side of the chariot. It was bathed in water and sacrificed alongside a hornless ram and a he-goat. It was dissected and its portions awarded to various deities.

The Roman Equus October ceremony involved a horse dedicated to Mars, the Roman god of war. The sacrifice took place on the Ides of October, but through ritual reuse was used in a spring festival (the Parilia). Two-horse chariot races determined the victim, which was the right-hand horse of the winning team. The horse is dismembered: the tail (cauda, possibly a euphemism for the penis) is taken to the Regia, the king’s residence, while two factions battle for possession of the head as a talisman for the coming year.

Among the Irish the ceremony was done in relation the the installation of a new king. In the presence of all the people a white mare is brought into their midst. Thereupon he who is to be elevated steps forward. Right thereafter the mare is killed and boiled piecemeal in water, and in the same water a bath is prepared for him. He gets into the bath and eats of the flesh that is brought to him, with his people standing around and sharing it with him. He also imbibes the broth in which he is bathed, not from any vessel, nor with his hand, but only with his mouth. When this is done right according to such unrighteous ritual, his rule and sovereignty are consecrated.

The Norse ceremony according to the description in Hervarar saga of the Swedish inauguration of Blot-Sweyn, the last or next to last pagan Germanic king, c. 1080: the horse is dismembered for eating and the blood is sprinkled on the sacred tree at Uppsala.

The Völsa þáttr mentions a Norse pagan ritual involving veneration of the penis of a slaughtered stallion. A freshly cut horse head was also used in setting up a nithing pole for a Norse curse.

The primary archaeological context of horse sacrifice are burials, notably chariot burials, but graves with horse remains reach from the Eneolithic well into historical times. Herodotus describes the execution of horses at the burial of a Scythian king, and Iron Age kurgan graves known to contain horses number in the hundreds. There are also frequent depositions of horses in burials in Iron Age India. The custom is by no means restricted to Indo-European populations, but is continued by Turkic tribes.

The Vedic horse sacrifice or Ashvamedha was a fertility and kingship ritual involving the sacrifice of a sacred gray or white stallion. Similar rituals may have taken place among Roman, Celtic and Norse people, but the descriptions are not so complete.

Psychopomp

The role of a psychopomp (literally meaning the “guide of souls”), creatures, spirits, angels, or deities in many religions whose responsibility is to escort newly deceased souls from Earth to the afterlife, is not to judge the deceased, but simply to provide safe passage.

Frequently depicted on funerary art, psychopomps have been associated at different times and in different cultures with horses, whip-poor-wills, ravens, dogs, crows, owls, sparrows, cuckoos, and harts. When seen as birds, they are often seen in huge masses, waiting outside the home of the dying.

Classical examples of a psychopomp in Greek, Roman and Egyptian mythology are Charon, Vanth, Hermes, Hecate, Mercury and Anubis. In many beliefs, when a spirit is being taken to the underworld, they will be violently ripped from their bodies.

In Jungian psychology, the psychopomp is a mediator between the unconscious and conscious realms. It is symbolically personified in dreams as a wise man or woman, or sometimes as a helpful animal. In many cultures, the shaman also fulfills the role of the psychopomp. This may include not only accompanying the soul of the dead, but also vice versa: to help at birth, to introduce the newborn child’s soul to the world.

Rhiannon and Epona

Rhiannon, a major and classic figure in the earliest prose literature and mythology of Britain, the Mabinogi, or Epona (“Great Mare”), in Gallo-Roman religion a protector of horses, donkeys, and mules, is the corresponding horse goddess of fertility or even mother goddess, associated with both, sun and moon.

Epona and her horses might also have been leaders of the soul in the after-life ride, or psychopomps, with parallels in Rhiannon of the Mabinogion.

Like some other figures of British/ Welsh literary tradition, Rhiannon may be a reflex of an earlier Celtic deity. Her name appears to derive from the reconstructed Brittonic form *Rīgantōna, a derivative of *rīgan- “queen”. In the First Branch Rhiannon is strongly associated with horses, and so is her son Pryderi. She is often considered to be related to the Gaulish horse goddess Epona.

The resemblance is her horse affinity, and her son’s, as mare and foal; also a paradoxical way of sitting on her horse in a calm, static way, like a key image of Epona. While this is generally accepted connection among scholars of the Mabinogi and Celtic studies, Ronald Hutton as a general historian, is sceptical.

The worship of Epona, “the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself”, was widespread in the Roman Empire between the first and third centuries AD; this is unusual for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities.

Epona is mentioned in The Golden Ass by Apuleius, where an aedicular niche with her image on a pillar in a stable has been garlanded with freshly picked roses. In his Satires, the Roman poet Juvenal also links the worship and iconography of Epona to the area of a stable. Small images of Epona have been found in Roman sites of stables and barns over a wide territory.

The probable date of c. 1400 BC ascribed to the giant chalk horse carved into the hillside turf at Uffington, in southern England, is too early to be directly associated with Epona a millennium and more later, but clearly represents a Bronze Age totem of some kind.