Semitic languages

There are several locations proposed as possible sites for prehistoric origins of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia, the Levant, Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa, with the most recent Bayesian studies indicating Semitic originated in the Levant circa 3800 BC, and was later also introduced to the Horn of Africa in approximately 800 BC.

Semitic languages were spoken across much of the Middle East and Asia Minor during the Bronze Age and Iron Age, the earliest attested being the East Semitic Akkadian of the Mesopotamian and south eastern Anatolian polities of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia, and the also East Semitic Eblaite language of the kingdom of Ebla in the north eastern Levant.

The 5.9 kiloyear event was one of the most intense aridification events during the Holocene, the current geological epoch that began after the last glacial period approximately 11,650 years before present.

It occurred around 3900 BC, ending the Neolithic Subpluvial, or the Holocene Wet Phase, an extended period from about 7500–7000 BCE to about 3500–3000 BCE of wet and rainy conditions in the climate history of northern Africa both preceded and followed by much drier periods.

The 5.9 kiloyear event is associated with the last round of the Sahara pump theory, and probably initiated the most recent desiccation of the Sahara, as well as a five century period of colder climate in more northerly latitudes.

It triggered human migration to the Nile, which eventually led to the emergence of the first complex, highly organized, state-level societies in the 4th millennium BC. It may have contributed to the decline of Old Europe and the first Indo-European migrations into the Balkans from the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

For some reason, all the earlier arid events (including the 8.2 kiloyear event) were followed by recovery, as is attested by the wealth of evidence of humid conditions in the Sahara between 10,000 and 6,000 BP. However, it appears that the 5.9 kiloyear event was followed by a partial recovery at best, with accelerated desiccation in the millennium that followed.

For example, Cremaschi (1998) describes evidence of rapid aridification in Tadrart Acacus of southwestern Libya, in the form of increased aeolian erosion, sand incursions and the collapse of the roofs of rock shelters.

In the eastern Arabian Peninsula, the 5.9 kiloyear event may have contributed to an increase in relatively greater social complexity and have corresponded to an end of the local Ubaid period and the emergence of the first state societies at the lower end of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in southern Mesopotamia.

In central North Africa it triggered human migration to the Nile, which eventually led to the emergence of the second complex, highly organized, state-level societies in the 4th millennium BC.

By causing a period of cooling in Europe, it may have contributed to the decline of Old Europe and the first Indo-European migrations into the Balkans from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. Around 4200–4100 BCE a climate change occurred, manifesting in colder winters in Europe.

Between 4200–3900 BCE many tell settlements in the lower Danube Valley were burned and abandoned, while the Cucuteni-Tripolye culture showed an increase in fortifications, meanwhile moving eastwards towards the Dniepr. Steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

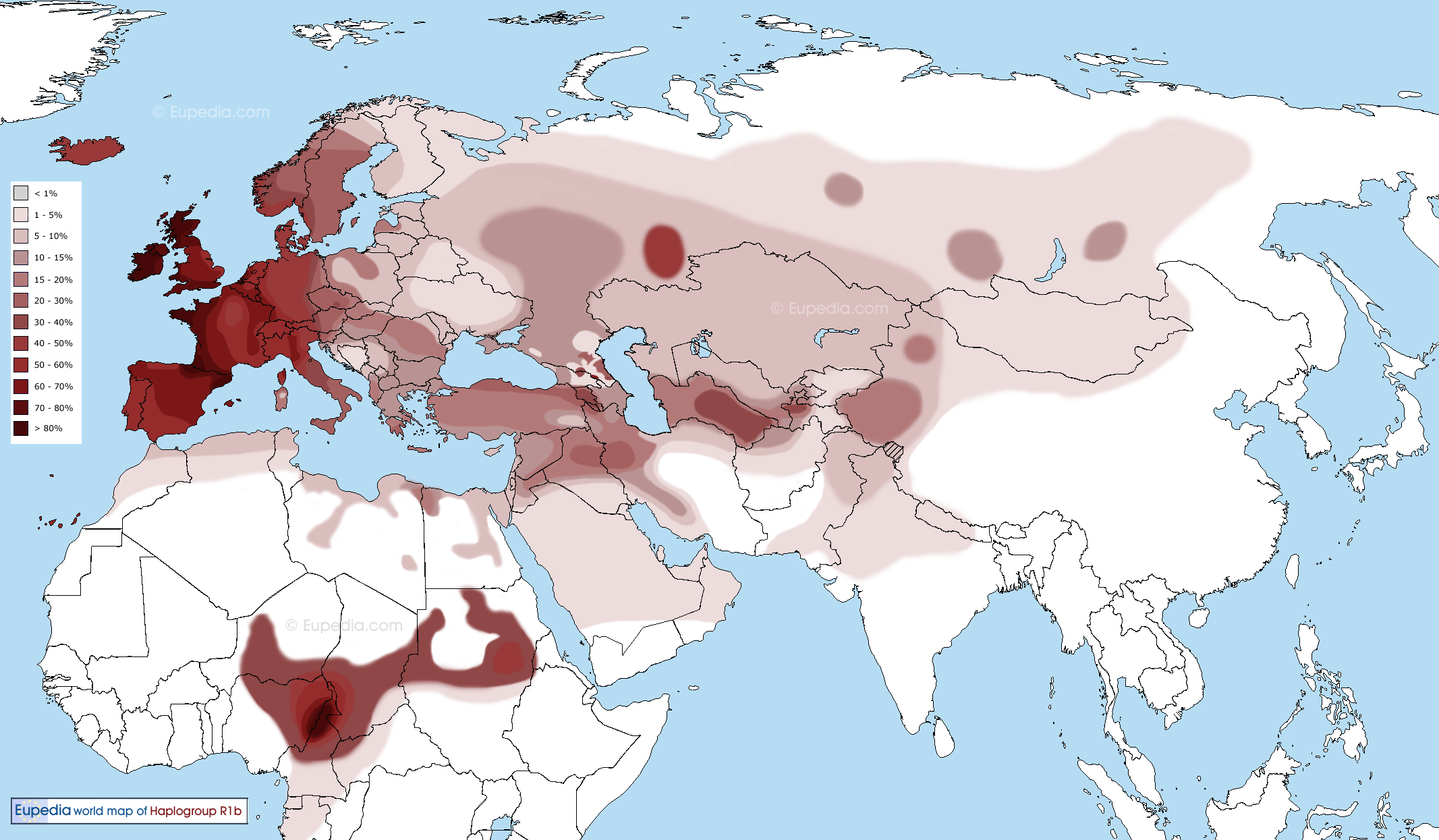

The Levantine & African branch of R1b (V88)

It has been hypothetised that R1b people (perhaps alongside neighbouring J2 tribes) were the first to domesticate cattle in northern Mesopotamia some 10,500 years ago. The oldest forms of R1b (M343, P25, L389) are found dispersed at very low frequencies from Western Europe to India, a vast region where could have roamed the nomadic R1b hunter-gatherers during the Ice Age.

The three main branches of R1b1 (R1b1a, R1b1b, R1b1c) all seem to be associated with the domestication of cattle in northern Mesopotamia. The southern branch, R1b1c (V88), is found mostly in the Levant and Africa. The northern branch, R1b1a (P297), seems to have originated around the Caucasus, eastern Anatolia or northern Mesopotamia, then to have crossed over the Caucasus, from where they would have invaded Europe and Central Asia. R1b1b (M335) has only been found in Anatolia.

Both R1b-M269 and R1b-V88 probably split soon after cattle were domesticated, approximately 10,500 years ago (8,500 BCE). R1b-V88 migrated south towards the Levant and Egypt. The R-V88 coalescence time was estimated at 9200–5600 kya, in the early mid Holocene. The migration of R1b people can be followed archeologically through the presence of domesticated cattle, which appear in central Syria around 8,000-7,500 BCE (late Mureybet period), then in the Southern Levant and Egypt around 7,000-6,500 BCE (e.g. at Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba).

Cattle herders subsequently spread across most of northern and eastern Africa. The Sahara desert would have been more humid during the Neolithic Subpluvial period (c. 7250-3250 BCE), and would have been a vast savannah full of grass, an ideal environment for cattle herding.

Evidence of cow herding during the Neolithic has shown up at Uan Muhuggiag in central Libya around 5500 BCE, at the Capeletti Cave in northern Algeria around 4500 BCE. But the most compelling evidence that R1b people related to modern Europeans once roamed the Sahara is to be found at Tassili n’Ajjer in southern Algeria, a site famous pyroglyphs (rock art) dating from the Neolithic era. Some painting dating from around 3000 BCE depict fair-skinned and blond or auburn haired women riding on cows.

The oldest known R1b-V88 sample in Europe is a 6,200 year-old farmer/herder from Catalonia. Autosomally this individual was a typical Near Eastern farmer, possessing just a little bit of Mesolithic West European admixture. After reaching the Maghreb, R1b-V88 cattle herders could have crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Iberia, probably accompanied by G2 farmers, J1 and T1a goat herders. These North African Neolithic farmers/herders could have been the ones who established the Almagra Pottery culture in Andalusia in the 6th millennium BCE.

Nowadays small percentages (1 to 4%) of R1b-V88 are found in the Levant, among the Lebanese, the Druze, and the Jews, and almost in every country in Africa north of the equator. Higher frequency in Egypt (5%), among Berbers from the Egypt-Libya border (23%), among the Sudanese Copts (15%), the Hausa people of Sudan (40%), the Fulani people of the Sahel (54% in Niger and Cameroon), and Chadic tribes of northern Nigeria and northern Cameroon (especially among the Kirdi), where it is observed at a frequency ranging from 30% to 95% of men.

R-V88 is a paternal genetic record of the proposed mid-Holocene migration of proto-Chadic Afroasiatic speakers through the Central Sahara into the Lake Chad Basin, and geomorphological evidence is consistent with this view.

A date 6000 BC was estimated for the L3f3 sub-haplogroup, which is in good agreement with the supposed migration of Chadic speaking pastoralists and their linguistic differentiation from other Afro-Asiatic groups of East Africa. This is consistent with the date for V88 proposed at 7,200-3,600 BC, and is also a very close match for the arrival of the Neolithic in Africa.

R1b-V88 would have crossed the Sahara between 7,200 and 3,600 BC, and is most probably associated with the diffusion of Chadic languages, a branch of the Afroasiatic languages that is spoken in parts of the Sahel. They include 150 languages spoken across northern Nigeria, southern Niger, southern Chad, Central African Republic and northern Cameroon. The most widely spoken Chadic language is Hausa, a lingua franca of much of inland Eastern West Africa.

Several modern genetic studies of Chadic speaking groups in the northern Cameroon region have observed high frequencies of the Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R1b in these populations (specifically, of R1b’s R-V88 variant). This paternal marker is common in parts of West Eurasia, but otherwise rare in Africa. Cruciani et al. (2010) thus propose that the Proto-Chadic speakers during the mid-Holocene (5000 BC) migrated from the Levant to the Central Sahara, and from there settled in the Lake Chad Basin.

V88 would have migrated from Egypt to Sudan, then expanded along the Sahel until northern Cameroon and Nigeria. However, R1b-V88 is not only present among Chadic speakers, but also among Senegambian speakers (Fula-Hausa) and Semitic speakers (Berbers, Arabs).

The only Afro-Asiatic speaking group that the Chadic speakers plot closely to is Cushitic, which will probably make Blench happy, as he claims Chadic speakers are a split-off from Cushitic speaking pastoralists. It’s fairly obvious that the male line of Chadic speakers followed a path into Africa via the Sinai, then down the West bank of the Nile and then struck out West to Lake Chad, acquiring wives as they went.

The only issue is the exact date. Holocene or Neolithic? Whatever the exact date, this brings the argument for an Asian origin for Afro-Asiatic out again, as (from the DNA here) the odds are 50% that it followed the male line in from Asia.

Chadic has cognates for sheep and goats that look like they share a root with Cushitic and Egyptian, which would at least date proto Chadic to the Neolithic, making the mt DNA date of 8,000 more likely to be close to the actual date for V88 to enter Africa.

R1b-V88 is found among the native populations of Rwanda, South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau. The wide distribution of V88 in all parts of Africa, its incidence among herding tribes, and the coalescence age of the haplogroup all support a Neolithic dispersal. In any case, a later migration out of Egypt would be improbable since it would have brought haplogroups that came to Egypt during the Bronze Age, such as J1, J2, R1a or R1b-L23.

The maternal lineages associated with the spread of R1b-V88 in Africa are mtDNA haplogroups J1b, U5 and V, and perhaps also U3 and some H subclades.

The origin and development of the African haplogroup R1b

Genetic substrates in Afro-Asiatic language speaking populations

The relation between Egypt and Southwest Asia

From the Levant to the Great Rift Valley (Savanna Pastoral Neolithic)

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, around 8500-5500 BCE) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic), as the domestication of plants and animals was in its formative stages, having possibly been induced by the Younger Dryas. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2 kiloyear event, a cool spell centred on 6200 BCE that lasted several hundred years.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic is divided into Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA 8500 BCE – 7600 BCE) and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB 7600 BCE – 6000 BCE). These were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). The Pre-Pottery Neolithic precedes the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). At ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan the culture continued a few more centuries as the so-called Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture.

Around 8000 BCE during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) the world’s first town Jericho appeared in the Levant. PPNB differed from PPNA in showing greater use of domesticated animals, a different set of tools, and new architectural styles. The period is dated to between ca. 10,700 and ca. 8,000 BP or 7000 – 6000 BCE. Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Mesolithic Natufian culture. However, it shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of north eastern Anatolia.

The culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BCE, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries. In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of the Ghassulian culture.

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period, which existed between 8,200 and 7,900 BP. Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6200 BCE, partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon animal domesticates, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in Southern Palestine, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B fossils that were analysed for ancient DNA were found to carry the Y-DNA (paternal) haplogroups E1b1b (2/7; ~29%), CT (2/7; ~29%), E (xE2, E1a, E1b1a1a1c2c3b1, E1b1b1b1a1, E1b1b1b2b) (1/7; ~14%), T(xT1a1,T1a2a) (1/7; ~14%), and H2 (1/7; ~14%). The CT clade was also observed in a Pre-Pottery Neolithic C specimen (1/1; 100%). Maternally, the rare basal haplogroup N* has been found among skeletal remains belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, as have the mtDNA clades L3 and K.

Ancient DNA analysis has also confirmed ancestral ties between the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture bearers and the makers of the Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian culture of the Maghreb, the Mesolithic Natufian culture of the Levant, the Early Neolithic Ifri n’Amr or Moussa culture of the Maghreb, the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of East Africa, the Late Neolithic Kelif el Boroud culture of the Maghreb, and the Ancient Egyptian culture of the Nile Valley, with fossils associated with these early cultures all sharing a common genomic component.

The A-Group culture was an ancient civilization that flourished between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Nubia. It lasted from c. 3800 BC to c. 3100 BC. The A-Group makers maintained commercial ties with the Ancient Egyptians. They traded commodities like incense, ebony and ivory, which were gathered from the southern riverine area. They also bartered carnelian from the Western Desert as well as gold mined from the Eastern Desert in exchange for Egyptian products, olive oil and other items from the Mediterranean basin.

The A-Group culture came to an end around 3100 BC, when it was quashed by the First Dynasty rulers of Egypt. Reisner originally identified a B-Group culture, however this theory became obsolete when H.S. Smith demonstrated that the “B-Group” was an impoverished manifestation of the A-Group culture

Dental trait analysis of A-Group fossils found that they were closely related to Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting Northeast Africa and the Maghreb. Among the ancient populations, the A-Group people were nearest to the Kerma culture bearers and Kush populations in Upper Nubia, followed by the Meroitic, X-Group and Christian period inhabitants of Lower Nubia and the Kellis population in the Dakhla Oasis, as well as C-Group and Pharaonic era skeletons excavated in Lower Nubia and ancient Egyptians (Naqada, Badari, Hierakonpolis, Abydos and Kharga in Upper Egypt; Hawara in Lower Egypt).

Among the recent groups, the A-Group makers were morphologically closest to Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa, followed by the Shawia and Kabyle Berber populations of Algeria as well as Bedouin groups in Morocco, Libya and Tunisia. The A-Group skeletons and these ancient and recent fossils were also phenotypically distinct from those belonging to recent Negroid populations in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The C-Group culture was an ancient civilization centered in Nubia, which existed from ca. 2400 BCE to ca. 1550 BCE. The C-Group arose after Reisner’s A-Group and B-Group cultures, and around the time the Old Kingdom was ending in Ancient Egypt.

While today many scholars see A and B as actually being a continuation of the same group, C-Group is more distinct. The C-Group is marked by its distinctive pottery, and for its tombs. Early C-Group tombs consisted of a simple “stone circle” with the body buried in a depression in the centre. The tombs later became more elaborate with the bodies being placed in a stone lined chamber, and then the addition of an extra chamber on the east: for offerings.

The origins of the C-Group are still uncertain. Some scholars see it largely being evolved from the A/B-Group. Others think it more likely that the C-Group was brought by invaders or migrants that mingled with the local culture, with the C-Group perhaps originating in the then rapidly drying Sahara.

The C-Group were farmers and semi-nomadic herders keeping large numbers of cattle in an area that is today too arid for such herding. Most of what is known about the C-Group peoples comes from Lower Nubia, due to the extensive archaeological work conducted in that region. The northern border of the C-Group was around Kubaniek. The southern border is still uncertain, but C-Group sites have been found as far south as Eritrea.

During the Egyptian Sixth Dynasty, Lower Nubia is described of consisting of a number of small states, three of which are named: Setju, Wawat, and Irjet. At this same time in Upper Nubia the Kingdom of Kerma was emerging. The exact relation between the C-Group and Kerma are uncertain, but early Kerma shows definite similarities to the C-Group culture.

Under the Middle Kingdom much of the C-Group lands in Lower Nubia were conquered by Egypt; after the Egyptians left, Kerma expanded north controlling the region. With the conquest of Nubia by Egypt under Tuthmosis I in the late 16th century BCE, the C-Group disappears, merged, along with Kerma, into the Egyptianized Kush.

Dental trait analysis of C-Group fossils found that they were closely related to other Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting Northeast Africa and the Maghreb. Among the ancient populations, the C-Group people were nearest to the ancient Egyptians (Naqada, Badari, Hierakonpolis, Abydos and Kharga in Upper Egypt; Hawara in Lower Egypt) and Pharaonic era skeletons excavated in Lower Nubia, followed by the A-Group culture bearers of Lower Nubia, the Kerma and Kush populations in Upper Nubia, the Meroitic, X-Group and Christian period inhabitants of Lower Nubia, and the Kellis population in the Dakhla Oasis.

Among the recent groups, the C-Group markers were morphologically closest to the Shawia and Kabyle Berber populations of Algeria as well as Bedouin groups in Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, followed by other Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa. The C-Group skeletons and these ancient and recent fossils were also phenotypically distinct from those belonging to recent Negroid populations in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Linguistic evidence indicates that the C-Group peoples spoke Afro-Asiatic languages of the Berber branch. The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of Berber origin, including the terms for sheep and water (e.g., Nile). This in turn suggests that the C-Group population — which, along with the Kerma Culture, inhabited the Nile Valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers — spoke Afro-Asiatic languages.

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia), as well as the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and parts of the African Great Lakes region (Tanzania and Kenya).

Historical linguistic analysis and archaeogenetics indicate that the languages spoken in the ancient Kerma Culture of present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan, as well as those spoken in the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture (formerly known as the Stone Bowl Culture) of the Great Lakes region, a collection of ancient societies that appeared in the Rift Valley of East Africa and surrounding areas during a time period known as the “Pastoral Neolithic”, likely spoke South Cushitic languages of the Afroasiatic family.

The Kerma culture or Kerma kingdom was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BCE to 1500 BCE in ancient Nubia, located in Upper Egypt and northern Sudan. The polity seems to have been one of a number of Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

In the Kingdom of Kerma’s latest phase, lasting from about 1700–1500 BCE, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Sai and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt. Around 1500 BCE, it was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. By the eleventh century BCE, the more-Egyptianized Kingdom of Kush emerged, possibly from Kerma, and regained the region’s independence from Egypt.

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt between circa 2050 BC and 1710 BC, stretching from the reunification of Egypt under the impulse of Mentuhotep II of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty.

Some scholars also include the Thirteenth Dynasty of Egypt wholly into this period as well, in which case the Middle Kingdom would finish c. 1650, while others only include it until Merneferre Ay c. 1700 BC, last king of this dynasty to be attested in both Upper and Lower Egypt. During the Middle Kingdom period, Osiris became the most important deity in popular religion.

The Kingdom of Kush or Kush was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, located at the confluences of the Blue Nile, White Nile and the Atbarah River in what are now Sudan and South Sudan. Geographically, Kush referred to the region south of the first cataract in general. Mentuhotep II (21st century BC founder of the Middle Kingdom) is recorded to have undertaken campaigns against Kush in the 29th and 31st years of his reign. This is the earliest Egyptian reference to Kush; the Nubian region had gone by other names in the Old Kingdom.

The Kushite era of rule in Nubia was established after the Late Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt. Kush was centered at Napata during its early phase. After Kashta (“the Kushite”) invaded Egypt in the 8th century BC, the monarchs of Kush were also the pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, until they were expelled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire under the rule of Esarhaddon a century later.

Writing was introduced to Kush in the form of the Egyptian-influenced Meroitic alphabet circa 700–600 BC, although it appears to have been wholly confined to the royal court and major temples. During classical antiquity, the Kushite imperial capital was located at Meroë. According to partially deciphered Meroitic texts, the name of the city was Medewi or Bedewi. The Kingdom of Kush which housed the city of Meroë represents one of a series of early states located within the middle Nile. It is one of the earliest and most impressive states found south of the Sahara.

The culture of Meroë developed from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, which originated in Kush. The importance of the town gradually increased from the beginning of the Meroitic Period, especially from the reign of Arakamani (c. 280 BCE) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë from Napata (Gebel Barkal). In the fifth century BCE, Greek historian Herodotus described it as “a great city…said to be the mother city of the other Ethiopians.”

In early Greek geography, the Meroitic kingdom was known as Aethiopia. The Kingdom of Kush with its capital at Meroe persisted until the 4th century AD, when it weakened and disintegrated due to internal rebellion. The seat was eventually captured and burnt to the ground by the Kingdom of Aksum. The collapse of their external trade with other Nile Valley states may be considered as one of the prime causes of the decline of royal power and disintegration of the Meroitic state in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE.

Meroitic is an extinct language that is properly called Kushite after the attested autonym, k3š. “Meroitic” should properly be understood as a specific period (c. 300 BC – c. 350 AD) when Meroë was the royal capital of the Kingdom of Kush and a period in which the Kushite language was spoken and written. It is a similar circumstance with “Kerman” (c. 2500 BC – c. 1500 BC) and “Napatan” (664 BC – c. 300 BC).

During the Meroitic Period, the Kushite language was spoken from the area of the 1st Cataract of the Nile to the Khartoum area of Sudan. The Kushite language, by way of names, is possibly attested as early as Middle Kingdom Egypt’s 12th Dynasty (c. 2000 BC) in the Egyptian Execration texts concerning Kerma.

Both the Meroitic Period and the Kingdom of Kush itself ended with the fall of Meroë (c. 350 AD), but use of the Kushite language continued for a time after that event. The language likely became fully extinct by the 6th century when it was supplanted by Byzantine Greek, Coptic, and Old Nubian.

The Kushite language, during the Meroitic period, was written in two forms of the Meroitic alphasyllabary: Meroitic Cursive, which was written with a stylus and was used for general record-keeping; and Meroitic Hieroglyphic, which was carved in stone or used for royal or religious documents. The last known Meroitic inscription is written in Meroitic Cursive and dates to the 5th century. The Kushite language is poorly understood, owing to the scarcity of bilingual texts.

Ancient DNA analysis of a Savanna Pastoral Neolithic fossil excavated at the Luxmanda site in Tanzania likewise found that the specimen carried a large proportion of ancestry related to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture of the Levant, similar to that borne by modern Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting the Horn of Africa.

This suggests that the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture bearers may have been Cushitic speakers, who were gradually absorbed by neighboring hunter-gatherer communities in the lacustrine region. Through archaeology, historical linguistics and archaeogenetics, they conventionally have been identified with the area’s first Afroasiatic-speaking settlers. Archaeological dating of livestock bones and burial cairns has also established the cultural complex as the earliest center of pastoralism (cattle, goats and sheep) and stone construction in the region.

The makers of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture are believed to have arrived in the Rift Valley sometime during the Pastoral Neolithic period (c. 3,000 BCE-700 CE). Through a series of migrations from Northeast Africa, these early Cushitic-speaking pastoralists brought cattle and caprines southward from the Sudan and/or Ethiopia into northern Kenya, probably using donkeys for transportation.

According to archaeological dating of associated artifacts and skeletal material, they first settled in the lowlands of Kenya between 3,200 and 1,300 BC, a phase referred to as the Lowland Savanna Pastoral Neolithic. They subsequently spread to the highlands of Kenya and Tanzania around 1,300 BC, which is consequently known as the Highland Savanna Pastoral Neolithic phase.

The region was at the time of their arrival inhabited by Khoisan hunter-gatherers who spoke Khoisan languages and practiced an Eburran blade industry.[3] Early Nilotic settlers, who are thought to have spoken Southern Nilotic languages and been responsible for the pastoralist Elmenteitan culture, are also believed to have lived in the Rift Valley during that period.

A number of extinct populations are thought to have spoken Afroasiatic languages of the Cushitic branch. Christopher Ehret (1998) proposes that among these languages were the now extinct Tale and Bisha languages, which were identified on the basis of loanwords. These early Cushitic speakers in the region largely disappeared following the Bantu Expansion.

The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of proto-Highland East Cushitic origin, including the terms for sheep/goatskin, hen/cock, livestock enclosure, butter and milk. This in turn suggests that the Kerma population — which, along with the C-Group culture, inhabited the Nile Valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers — spoke Afroasiatic languages.