A composition of the Four Living Creatures into one tetramorph. Matthew the man, Mark the lion, Luke the ox, and John the eagle.

A 13th century Cluniac ivory carving of Christ in Majesty surrounded by the creatures of the tetramorph.

Letter resh – The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek Rho (Ρ), Etruscan Etruscan  , Latin R, and Cyrillic Р.

, Latin R, and Cyrillic Р.

Nr: 4 – 4 seasons – 4 elements in astrology – the Tetramorph

An excursus on the Egyptian word nTr

An Assyrian lamassu dated 721 BC.

According to the Talmudists, the emblem of Nergal was a cockerel and Nergal means a “dunghill cock”, although standard iconography pictured Nergal as a lion. The word “Gallus” is also the Latin word for rooster. A play upon his name—separated into three elements as Ne-uru-gal (light of the great Ûru; lord of the great dwelling)—expresses his position at the head of the nether-world pantheon.

Lahmu

Janus

Odin – the husband of the goddess Frigg

Óðr again leaves the grieving Freyja

Enki / Isimud – Saturn / Janus – Odin / Odr

Uranus

T – Tyr

Algiz – Heimdall

The symbol, reversed, might be used to access the realm of the dead, giants, and the unconscious.

Life and death

According to Macrobius who cites Nigidius Figulus and Cicero, Janus and Jana (Diana) are a pair of divinities, worshipped as Apollo or the sun and moon, whence Janus received sacrifices before all the others, because through him is apparent the way of access to the desired deity.

A similar solar interpretation has been offered by A. Audin, who interprets the god as the issue of a long process of development starting with the Sumerian culture from two solar pillars located on the eastern side of temples, each of them marking the direction of the rising sun at the dates of the two solstices. The southeastern corresponding to the Winter and the northeastern to the Summer solstice.

These two pillars would be at the origin of the theology of the divine twins, one of whom is mortal (related to the NE pillar, as confining with the region where the sun does not shine) and the other is immortal (related to the SE pillar and the region where the sun always shines). Later these iconographic models evolved in the Middle East and Egypt into a single column representing two torsos and finally a single body with two heads looking at opposite directions.

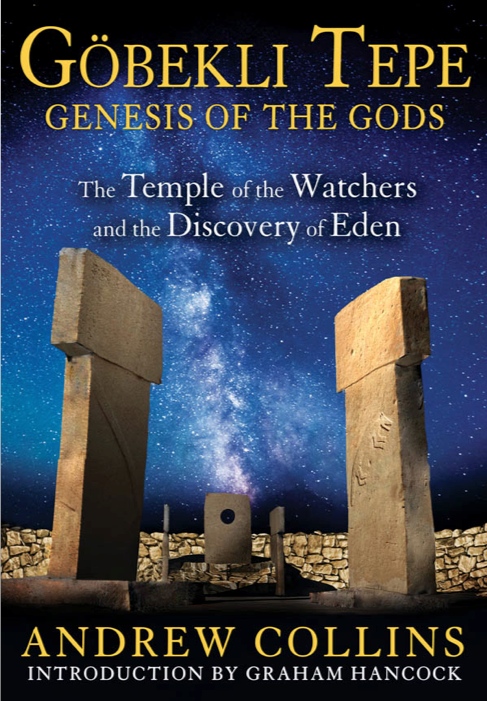

Göbekli Tepe, Turkish for “Potbelly Hill”, is an archaeological site in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, approximately 12 km (7 mi) northeast of the city of Şanlıurfa. The tell includes two phases of use believed to be of a social or ritual nature dating back to the 10th–8th millennium BCE.

During the first phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected – the world’s oldest known megaliths. More than 200 pillars in about 20 circles are currently known through geophysical surveys. Each pillar has a height of up to 6 m (20 ft) and weighs up to 10 tons. They are fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the bedrock.

In the second phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. The site was abandoned after the PPNB. Younger structures date to classical times.

The details of the structure’s function remain a mystery. It was excavated by a German archaeological team under the direction of Klaus Schmidt from 1996 until his death in 2014. Schmidt believed that the site was a sanctuary where people from a wide region periodically congregated, not a settlement.

Gobekli Tepe’s hilltop site was not defensive or residential and the indications are that it was a sacred area and that the two pillars outside the entrance of some of the circles represented a gateway between secular and religious ground.

Three layers could be distinguished up to now at the site. The oldest Layer III (10th millenium BC) is characterized by monolithic T-shaped pillars weighing tons, which were positioned in circle-like structures. The pillars were interconnected by limestone walls and benches leaning at the inner side of the walls. In the centre of these enclosures there are always two bigger pillars, with a height of over 5 m. The circles measure 10-20 m.

Two huge central pillars are surrounded by a circle formed by – at current state of excavation – 11 pillars of similar T-shape. Most of these pillars are decorated with depictions of animals, foxes, birds (e.g. cranes, storks and ducks), and snakes being the most common species in this enclosure, accompanied by a wide range of figurations including the motives of boar, aurochs, gazelle, wild donkey and larger carnivores.

In particular these central pillars of Enclosure D allow demonstrating the anthropomorphic appearance of the T-shaped pillars. They might have been gods who had T-shapes instead of heads because it was forbidden to see their faces. The T-shaped stones around the circle may have been their companions.

Gobekli Tepe’s hilltop site was not defensive or residential and the indications are that it was a sacred area and that the two pillars outside the entrance of some of the circles represented a gateway between secular and religious ground.

According to Andrew Collins the central pillars of Enclosure D target Deneb, the brightest star in the constellation of Cygnus, also known as the celestial bird, or swan, and one of the brightest stars in the night sky and one corner of the Summer Triangle, as it extinguishes on the north-northwestern horizon. Other structures at Göbekli Tepe were built perhaps with different considerations in mind. Enclosure B’s central pillars are unlikely to have targeted Deneb during the epoch in question.

The twin pillars marking the entrance to the apse in Enclosure A were orientated almost exactly northwest to southeast, while those in Enclosure F (a smaller, much later structure west of the main group) are aligned east-northeast or west-southwest, very close to the angle at which the sun rises on the summer solstice and sets on the winter solstice.

Though he was usually depicted with two faces looking in opposite directions as Janus Geminus (twin Janus) or Bifrons, in some places he was Janus Quadrifrons, or the four-faced. The Janus quadrifrons, although having a different meaning, seems to be connected to the same theological complex, as its image purports an ability to rule over every direction, element and time of the year. It did not give rise to a new epithet though.

Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, and endings, who is usually depicted as having two faces, since he looks to the future and to the past. Numa in his regulation of the Roman calendar called the first month Januarius after Janus, according to tradition considered the highest divinity at the time.

The lamassu (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒆗, an.kal; Sumerian: dlammař; Akkadian: lamassu; sometimes called a lamassus) is an Assyrian protective deity, often depicted as having a human head, the body of a bull or a lion, and bird wings. In some writings, it is portrayed to represent a female deity. A less frequently used name is shedu (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒆘, an.kal×bad; Sumerian: dalad; Akkadian, šēdu), which refers to the male counterpart of a lamassu. Lammasu represent the zodiacs, parent-stars or constellations.

The lamassu is a celestial being from ancient Mesopotamian religion bearing a human head, bull’s body, sometimes with the horns and the ears of a bull, and wings. It appears frequently in Mesopotamian art. In Assyro-Babylonian ecclesiastical art the great lion-headed colossi serving as guardians to the temples and palaces seem to symbolise Nergal, just as the bull-headed colossi probably typify Ninurta.

The lamassu and shedu were household protective spirits of the common Babylonian people, becoming associated later as royal protectors, and were placed as sentinels at entrances. In Sumerian times Laḫmu may have meant “the muddy one”. Lahmu guarded the gates of the Abzu temple of Enki at Eridu. He and his sister Laḫamu are primordial deities in the Babylonian Epic of Creation Enuma Elis and Lahmu may be related to or identical with “Lahamu”, one of Tiamat’s creatures in that epic.

Laḫmu is depicted as a bearded man with a red sash – usually with three strands – and four to six curls on his head and they are also depicted as monsters, which each encompasses a specific constellation. He is often associated with the Kusarikku or “Bull-Man”. Lahamu is sometimes seen as a serpent, and sometimes as a woman with a red sash and six curls on her head.

Ur(i)dimmu, the reading is uncertain, meaning “Mad/howling Dog” or Langdon’s “Gruesome Hound”, Sumerian UR.IDIM and giš.pirig.gal = ur-gu-lu-ú = ur-idim-[mu] in the lexical series ḪAR.gud = imrû = ballu, was an ancient Mesopotamian mythical creature in the form of a human headed dog-man or lion-man whose first appearance might be during the Kassite period, if the Agum-Kakrime Inscription proves to be a copy of a genuine period piece.

He is pictured standing upright, wearing a horned tiara and holding a staff with an uskaru, or lunar crescent, at the tip. The lexical series ḪAR-ra=ḫubullu describes him as a kalbu šegû, “rabid dog”, but due to the propensity for Sumerian culture to group canines and felines together (ur.maḫ, big dog = lion) and Akkadian to separate them (nēšu, labbu = lion), the issue remains unresolved although the prominent genitalia on the few extant representations argues for a canine interpretation.

His appearance was essentially the opposite, or complement of that of Ugallu, with a human head replacing that of an animal and an animal’s body replacing that of a human. He appears in later iconography paired with Kusarikku, “Bull-Man”, a similar anthropomorphic character, as attendants to the god Šamaš. He is carved as a guardian figure on a doorway in Aššur-bāni-apli’s north palace at Nineveh.

He appears as an intercessor with Marduk and Zarpanītu for the sick in rituals. He was especially revered in the Eanna in Uruk during the neo-Babylonian period where he seems to have taken on a cultic role, where the latest attestation was in the 29th year of Darius I.

As one of the eleven spawn of Tiamat in the Enûma Eliš vanquished by Marduk, he was displayed as a trophy on doorways to ward off evil and later became an apotropaic figurine buried in buildings for a similar purpose. He became identified as MUL- or dUR.IDIM with the constellation known by the Greeks as Wolf (Lupus).

Lupus is a constellation located in the deep Southern Sky. Its name is Latin for wolf. It is often found in association with the sun god and another mythical being called the Bison-man, which is supposedly related to the Greek constellation of Centaurus, a bright constellation in the southern sky.

In ancient times, the constellation was considered an asterism within the neighboring constellation Centaurus, and was considered to have been an arbitrary animal, killed, or about to be killed, on behalf of, or for, Centaurus. An alternative visualization, attested by Eratosthenes, saw this constellation as a wineskin held by Centaurus.

It was not separated from Centaurus until Hipparchus of Bithynia named it Therion (meaning beast) in the 2nd century BC. No particular animal was associated with it until the Latin translation of Ptolemy’s work identified it with the wolf.

Most of the brightest stars in Lupus are massive members of the nearest OB association, Scorpius-Centaurus, which is the nearest OB association to the Sun. This stellar association is composed of three subgroups (Upper Scorpius, Upper Centaurus–Lupus, and Lower Centaurus–Crux).

The Akkadians associated the god Papsukkal with a lamassu and the god Išum with shedu. Papsukkal was syncretized with Ninshubur, the messenger of the goddess Inanna. Much like Iris or Hermes in later Greek mythology, Ninshubur served as a messenger to the other gods. Hermes is identified with the Roman god Mercury.

In the Roman syncretism, Mercury was equated with the Celtic god Lugus, and in this aspect was commonly accompanied by the Celtic goddess Rosmerta, a goddess of fertility and abundance, her attributes being those of plenty such as the cornucopia.

Although Lugus may originally have been a deity of light or the sun (though this is disputed), similar to the Roman Apollo, his importance as a god of trade made him more comparable to Mercury, and Apollo was instead equated with the Celtic deity Belenus.

Romans also associated Mercury with the Germanic god Wotan or Odin. The day of the week Wednesday bears his name in many Germanic languages, including English. Mercury is the ruling planet of Gemini and is exalted in Virgo and/or Aquarius.

Odin is a frequent subject of study in Germanic studies, and numerous theories have been put forward regarding his development. Some of these focus on Odin’s particular relation to other figures; for example, the fact that Freyja’s husband Óðr appears to be something of an etymological doublet of the god, whereas Odin’s wife Frigg is in many ways similar to Freyja, and that Odin has a particular relation to the figure of Loki.

Isimud (also Isinu; Usmû; Usumu (Akkadian) is a minor god, the messenger of the god Enki, in Sumerian mythology. In ancient Sumerian artwork, Isimud is easily identifiable because he is always depicted with two faces facing in opposite directions in a way that is similar to the ancient Roman god Janus.

Isimud plays a similar role to Ninshubur, Inanna’s sukkal. Ninshubur (also known as Ninshubar, Nincubura or Ninšubur) was the sukkal or second-in-command of the goddess Inanna in Sumerian mythology. Her name means “Queen of the East” in ancient Sumerian. Much like Iris or Hermes in later Greek mythology, Ninshubur served as a messenger to the other gods.

Ishum is a minor god in Akkadian mythology, the brother of Shamash and an attendant of Erra. He may have been a god of fire and, according to texts, led the gods in war as a herald but was nonetheless generally regarded as benevolent. He developed from the Sumerian figure of Endursaga, the herald god in the Sumerian mythology. He leads the pantheon, particularly in times of conflict.

In Babylonian astronomy, the stars Castor and Pollux were known as the Great Twins (MUL.MASH.TAB.BA.GAL.GAL). The Twins were regarded as minor gods and were called Meshlamtaea and Lugalirra, meaning respectively ‘The One who has arisen from the Underworld’ and the ‘Mighty King’.

Both names can be understood as titles of Nergal, the major Babylonian god of plague and pestilence, who was king of the Underworld. Nergal is a deity that was worshipped throughout ancient Mesopotamia (Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia) with the main seat of his worship at Cuthah represented by the mound of Tell-Ibrahim. Other names for him are Erra and Irra.

He is a son of Enlil and Ninlil, along with Nanna (the moon) and Ninurta. Nergal seems to be in part a solar deity, sometimes identified with Shamash, but only representative of a certain phase of the sun. Portrayed in hymns and myths as a god of war and pestilence, Nergal seems to represent the sun of noontime and of the summer solstice that brings destruction, high summer being the dead season in the Mesopotamian annual cycle. He has also been called “the king of sunset”.

Over time Nergal developed from a war god to a god of the underworld. In the mythology, this occurred when Enlil and Ninlil gave him the underworld. Nergal was also the deity who presides over the netherworld. In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person.

In the late Babylonian astral-theological system Nergal is related to the planet Mars. As a fiery god of destruction and war, Nergal doubtless seemed an appropriate choice for the red planet, and he was equated by the Greeks to the war-god Ares (Latin Mars).

Amongst the Hurrians and later Hittites Nergal was known as Aplu, a name derived from the Akkadian Apal Enlil, (Apal being the construct state of Aplu) meaning “the son of Enlil”. Aplu may be related with Apaliunas who is considered to be the Hittite reflex of *Apeljōn, an early form of the name Apollo.

The national divinity of the Greeks, Apollo has been variously recognized as a god of music, truth and prophecy, healing, the sun and light, plague, poetry, and more. Apollo is the son of Zeus and Leto, and has a twin sister, the chaste huntress Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals and chastity in the ancient Greek religion and myth. Artemis is the Moon and Apollo is the Sun.

Many depictions use a female version of the widespread ancient motif of the male Master of Animals, showing a central figure with a human form grasping two animals, one to each side. The oldest depiction has been discovered in Çatalhöyük. Potnia Theron (“The Mistress of the Animals”) is a term first used (once) by Homer and often used to describe female divinities associated with animals.

According to Macrobius who cites Nigidius Figulus and Cicero, Janus and Jana (Diana) are a pair of divinities, worshipped as Apollo or the sun and moon, whence Janus received sacrifices before all the others, because through him is apparent the way of access to the desired deity.

In Germanic mythology, Týr (Old Norse), Tíw (Old English), and Ziu (Old High German) is a god. Stemming from the Proto-Germanic deity *Tīwaz and ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European deity *Dyeus, little information about the god survives beyond Old Norse sources. Due to the etymology of the god’s name and the shadowy presence of the god in the extant Germanic corpus, some scholars propose that Týr may have once held a more central place among the deities of early Germanic mythology.

Týr is the namesake of the Tiwaz rune, a letter of the runic alphabet corresponding to the Latin letter T. By way of the process of interpretatio germanica, the deity is the namesake of Tuesday (‘Týr’s day’) in Germanic languages, including English.

Interpretatio romana, in which Romans interpret other gods as forms of their own, generally renders the god as Mars, the ancient Roman war god, and it is through that lens that most Latin references to the god occur. For example, the god may be referenced as Mars Thingsus (Latin ‘Mars of the Thing’) on 3rd century Latin inscription, reflecting a strong association with the Germanic thing, a legislative body among the ancient Germanic peoples still in use among some of its modern descendants.

In Norse mythology, from which most narratives about gods among the Germanic peoples stem, Týr sacrifices his arm to the monstrous wolf Fenrir, who bites off his limb while the gods bind the animal. Týr is foretold to be consumed by the similarly monstrous dog Garmr during the events of Ragnarök. In Old Norse sources, Týr is alternately described as the son of the jötunn Hymir (in Hymiskviða) or of the god Odin (in Skáldskaparmál).

The Old Norse theonym Týr has cognates including Old English tíw and tíʒ, and Old High German Ziu. A cognate form appears in Gothic to represent the T rune (discussed in more depth below). Like Latin Jupiter and Greek Zeus, Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz ultimately stems from the Proto-Indo-European theonym *Dyeus. Outside of its application as a theonym, the Old Norse common noun týr means ‘(a) god’ (plural tívar). In turn, the theonym Týr may be understood to mean “the god”.

According to Tacitus’s Germania (AD 98), Tuisto (or Tuisco) is the divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and comparisons to figures in later (particularly Norse) Germanic mythology.

The Germania manuscript corpus contains two primary variant readings of the name. The most frequently occurring, Tuisto, is commonly connected to the Proto-Germanic root *twai – “two” and its derivative *twis – “twice” or “doubled”, thus giving Tuisto the core meaning “double”.

Any assumption of a gender inference is entirely conjectural, as the tvia/tvis roots are also the roots of any number of other concepts/words in the Germanic languages. Take for instance the Germanic “twist”, which, in all but the English has the primary meaning of “dispute/conflict”.

The second variant of the name, occurring originally in manuscript E, reads Tuisco. One proposed etymology for this variant reconstructs a Proto-Germanic *tiwisko and connects this with Proto-Germanic *Tiwaz, giving the meaning “son of Tiu”. This interpretation would thus make Tuisco the son of the sky-god (Proto-Indo-European *Dyeus) and the earth-goddess.

Connections have been proposed between the 1st century figure of Tuisto and the hermaphroditic primeval being Ymir in later Norse mythology, attested in 13th century sources, based upon etymological and functional similarity. Meyer (1907) sees the connection as so strong, that he considers the two to be identical.

Lindow (2001), while mindful of the possible semantic connection between Tuisto and Ymir, notes an essential functional difference: while Ymir is portrayed as an “essentially… negative figure” – Tuisto is described as being “celebrated” (celebrant) by the early Germanic peoples in song, with Tacitus reporting nothing negative about Tuisto.

Tacitus relates that “ancient songs” (Latin carminibus antiquis) of the Germanic peoples celebrated Tuisto as “a god, born of the earth” (deum terra editum). These songs further attributed to him a son, Mannus, who in turn had three sons, the offspring of whom were referred to as Ingaevones, Herminones and Istaevones, living near the Ocean (proximi Oceano). The names Mannus and Tuisto/Tuisco seem to have some relation to Proto-Germanic Mannaz, “man” and Tiwaz, “Tyr, the god”.

Dyēus or Dyēus Phter (Proto-Indo-European: *dyḗws, also *Dyḗus Ph2tḗr or Dyēus Pətḗr, alternatively spelled dyēws) is believed to have been the chief deity in Proto-Indo-European mythology. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in Proto-Indo-European society.

Dīs Pater was a Roman god of the underworld. Dis was originally associated with fertile agricultural land and mineral wealth, and since those minerals came from underground, he was later equated with the chthonic deities Pluto (Hades) and Orcus.

The name Ploutōn came into widespread usage with the Eleusinian Mysteries, in which Pluto was venerated as a stern ruler but the loving husband of Persephone. The couple received souls in the afterlife, and are invoked together in religious inscriptions. Hades, by contrast, had few temples and religious practices associated with him, and he is portrayed as the dark and violent abductor of Persephone.

In De Natura Deorum, Cicero derives the name of Dīs Pater from the Latin dives (“wealth, riches”), suggesting a meaning of “father of riches” (Pater is “father” in Latin), directly corresponding to the name Pluto, Pluto simply being how Plouton (“the rich one”) in Greek is spelled is Latin. Alternatively, he may be a secondary reflex of the same god as Jupiter (Proto-Indo-European Dyeus Ph₂ter or “Zeus-Pater”).

Dingir (𒀭, usually transliterated DIĜIR, Sumerian pronunciation: [tiŋiɾ]) is a Sumerian word for “god.” Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript “D” as in e.g. DInanna.

The cuneiform sign by itself was originally an ideogram for the Sumerian word an (“sky” or “heaven”); its use was then extended to a logogram for the word diĝir (“god” or goddess) and the supreme deity of the Sumerian pantheon An, and a phonogram for the syllable /an/. Akkadian took over all these uses and added to them a logographic reading for the native ilum and from that a syllabic reading of /il/. In Hittite orthography, the syllabic value of the sign was again only an.

The concept of “divinity” in Sumerian is closely associated with the heavens, as is evident from the fact that the cuneiform sign doubles as the ideogram for “sky”, and that its original shape is the picture of a star. The original association of “divinity” is thus with “bright” or “shining” hierophanies in the sky.

Adapa was a Mesopotamian mythical figure who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story, commonly known as “Adapa and the South Wind”, is known from fragmentary tablets from Tell el-Amarna in Egypt (around 14th century BC) and from finds from the Library of Ashurbanipal, Assyria (around 7th century BC).

Adapa was an important figure in Mesopotamian religion. His name would be used to invoke power in exorcism rituals. He also became an archetype for a wise ruler. In that context, his name would be invoked to evoke favorable comparisons. Some scholars conflate Adapa and the Apkallu known as Uanna. There is some evidence for that connection, but the name “adapa” may have also been used as an epithet, meaning “wise”.

Adapa was a mortal man, a sage or priest of temple of Enki in the city of Eridu. He had been given the gift of great wisdom by the god Enki, but not eternal life. While carrying out his duties, he was fishing the Persian Gulf. The sea became rough by the strong wind, and his boat was capsized. Angry, Adapa “broke the wings of the south wind” preventing it from blowing for seven days.

The god Anu called Adapa to account for his action, but the god Ea aided him by instructing Adapa to gain the sympathy of Tammuz and Gishzida[b], who guard the gates of heaven and not to eat or drink there, as such food might kill him. When offered garments and oil, he should put on the clothes on and anoint himself.

Adapa puts on mourning garments, and when he meets Tammuz and Gishzida, he claims to be in mourning because they have disappeared from the land. Adapa is then offered the “food of life” and “water of life” but will not eat or drink. Then garments and oil are offered, and he does what he had been told. He is brought before Anu, who asks why he will not eat or drink. Adapa replies that Enki told him not to.

Anu laughs at Enki’s actions, and passes judgment on Adapa by asking rhetorically, “What ill has he [Adapa] brought on mankind?” He adds that men will suffer disease as a consequence, which Ninkarrak (Nintinugga), a Babylonian goddess of healing, the consort of Ninurta, may ally. Adapa is then sent back down to earth.

Algiz (also Elhaz) is the name conventionally given to the “z-rune” ᛉ of the Elder Futhark runic alphabet. Its transliteration is z, understood as a phoneme of the Proto-Germanic language, the terminal *z continuing Proto-Indo-European terminal *s. The shape of the rune may be derived from that a letter expressing /x/ in certain Old Italic alphabets (𐌙), which was in turn derived from the Greek letter Ψ which had the value of /kʰ/ (rather than /ps/) in the Western Greek alphabet.

Because this specific phoneme was lost at an early time, the Elder Futhark rune underwent changes in the medieval runic alphabets. In the Anglo-Saxon futhorc it retained its shape, but it was given the sound value of Latin x. This is a secondary development, possibly due to runic manuscript tradition, and there is no known instance of the rune being used in an Old English inscription.

In Proto-Norse and Old Norse, the Germanic *z phoneme developed into an R sound, perhaps realized as a retroflex approximant [ɻ], which is usually transcribed as ʀ. This sound was written in the Younger Futhark using the Yr rune ᛦ, the Algiz rune turned upside down, from about the 7th century. This phoneme eventually became indistinguishable from the regular r sound in the later stages of Old Norse, at about the 11th or 12th century.

Algiz is the rune of higher vibrations, the divine plan and higher spiritual awareness. The energy of Algiz is what makes something feel sacred as opposed to mundane. It represents the worlds of Asgard (gods of the Aesir), Ljusalfheim (The Light Elves) and Vanaheim (gods of the Vanir), all connecting and sharing energies with our world, Midgard.

It is a powerful rune, because it represents the divine might of the universe. The white elk was a symbol to the Norse of divine blessing and protection to those it graced with sight of itself. The symbol, reversed, might be used to access the realm of the dead, giants, and the unconscious.