Kurgan stelae, or Balbals (supposedly from a Turkic word balbal meaning “ancestor” or “grandfather” or the Mongolic word “barimal” which means “handmade statue”) are anthropomorphic stone stelae, images cut from stone, installed atop, within or around kurgans (i.e. tumuli), in kurgan cemeteries, or in a double line extending from a kurgan. The stelae are also described as “obelisks” or “statue menhirs”.

Such stelae are found in large numbers in Southern Russia, Ukraine, Prussia, southern Siberia, Central Asia and Mongolia. Spanning more than three millennia, they are clearly the product of various cultures.

The earliest are associated with the Kura Araxes and Maykop culture, but they are more synonymous with the Pit Grave, or Yamna, culture of the Pontic-Caspian steppe. There are Iron Age specimens are identified with the Scythians and medieval examples with Turkic peoples.

The R1b people from the Middle East migrated across the Caucasus and established the Maykop culture, before expanding throughout the Pontic-Caspian Steppes and mixing with the indigenous R1a steppe people.

The tradition of burial mounds did not originated in the Pit-Grave culture from the steppes because new radiocarbon dating seemingly points that the burial mounds from the Maykop culture actually predate those found in the steppes.

Those of Maykop could trace their origins back to the Levant and Mesopotamia, two regions with relatively high levels of R1b, where the oldest subclades of R1b are to be found.

The R1b people brought both bronze working and the burial customs to the steppes. In that case, it becomes increasingly likely that the Proto-Indo-European language itself was also brought by the more advanced and dominant partner (R1b), and adopted by the R1a population at the same time as the rest of the cultural package from Maykop.

But it seems that the Satem branch of Indo-European languages (associated with R1a) diverged from the original Centum (R1b) because of the influence of the original R1a languages, which altered the pronunciation of IE words (namely, the sound change by which palatovelars became fricatives and affricates in satem languages).

Obviously Centum languages were later influenced by, and adopted words from the Chalcolithic people of Southeast Europe, then of Central and Western Europe. The languages evolve faster when new people were integrated into a linguistic community, bringing their own idioms with them.

Thirteen stelae, never before seen in Anatolia or the Near East, were found in 1998 in their original location at the centre of Hakkari, a city in the southeastern corner of Turkey. The stelae were carved on upright flagstone-like slabs measuring between 0.7 m to 3.10 m in height.

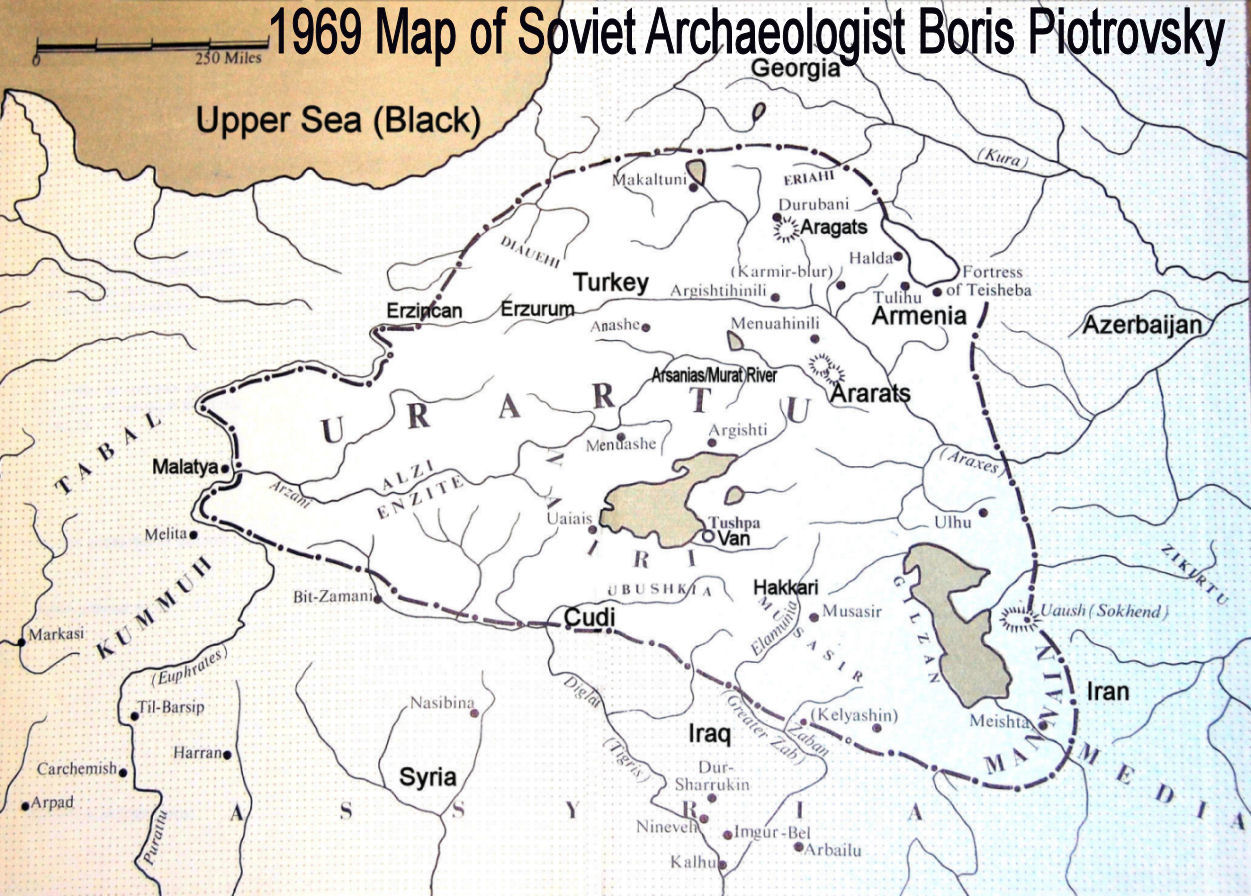

Many scholars believe that the Hakkâri region in the southeastern Turkish town of Hakkâri is the location of an independent kingdom known as Hubushkia, centered on the headwaters of the Great Zap River, that appears in the Assyrian annals of the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.

The names of some kings of Hubushkia, such as Kaki and Data or Dadi, are preserved in the Assyrian texts, which also record the relations between the Assyrian Empire and Hubushkia during the ninth century.

Assyrian expeditions crossed Hubushkia several times, receiving tribute from its kings, or taking it by force when they resisted. Disputed by Assyria to the southeast and the kingdom of Urartu to the northwest, Hubushkia eventually lost its independence.

The Hakkâri stelae may have belonged to the rulers of Hubushkia while it was an independent state. Certainly the complete lack of any Assyrian influence on the style of the reliefs indicates that they must have been produced prior to the last quarter of the ninth century B.C.

The stones contain only one cut surface, upon which human figures are chiseled. The theme of each stele reveals the foreview of an upper human body. The legs are not represented. Eleven of the stelae depict naked warriors with daggers, spears, and axes – masculine symbols of war. They always hold a drinking vessel made of skin in both hands. Two stelae contain female figures without arms. The stelae may have been carved by different craftsmen using different techniques.

Stylistic differences shift from bas relief to a more systematic linearity. The earliest stelae are in the style of bas relief while the latest ones are in a linear style. They were made during a period from the fifteenth century BC to the eleventh century BC in Hakkari. The best parallels for the Hakkâri stelae are found in the seventh-century B.C. through twelfth-century A.D. Kurgan stalae of the Eurasian steppe.

Stelae with this type of relief are not common in the ancient Near East however there are many close parallels between these and those produced by a variety of peoples from the Eurasian steppes between the third millennium BC and the eleventh century AD.

They may indicate a very early connection between this area and the Eurasian steppe. The Eurasian examples are connected to graves and cults of the dead. It is even thought that the balbal represent victims killed by the person who is buried in that particular grave.

A second excavation revealed a chamber tomb only about 50 feet from where stelae had been found. This chamber, which had been partly destroyed, appeared to have been in use for several hundred years from the mid-second millennium B.C. onward. Approximately 50 human skeletons were retrieved from this grave, along with a vast quantity of pottery, bronze daggers, ornamental pins, and gold and silver earrings.

Although it appears that this tomb had already gone out of use before the stelae were erected, there is a strong possibility that there may be other tombs found in the area. If excavation of the stelae site, planned for this summer, reveals nearby, contemporary chamber tombs, it might mean that the stelae are related to a cult of the dead.

For the moment, we may state that for whatever reason they were erected, it is certain that these stelae, which may represent the rulers of the kingdom of Hubushkia, were created under the influence of a Eurasian steppe culture that had infiltrated into the Near East.

Filed under: Uncategorized