Lepenski Vir (Лепенски Вир, Lepen Whirl) is an important Mesolithic archaeological site located in Serbia in the central Balkan peninsula. It consists of one large settlement with around ten satellite villages. The evidence suggests the first human presence in the locality around 7000 BC with the culture reaching its peak between 5300 BC and 4800 BC. Numerous piscine sculptures and peculiar architecture are testimony to a rich social and religious life led by the inhabitants and the high cultural level of these early Europeans.

Warmer global temperatures resulted in increased movement among human populations. The climate in southern Europe became warmer and wetter, and new plants began to flourish. In addition, people in the Balkan region began to develop better hunting methods which enabled larger groups of people to cooperate and live together. Most importantly, people in western Asia began to experiment with agricultural methods which enabled them to settle in one place for extended periods of time because of a surplus of food.

Due to gradual global warming, some of these people began to settle in southeastern Europe. The ice, which had isolated various human populations, was no longer a barrier. The influx of people from settled villages in South West Asia resulted in an increase in genetic variation as these different groups began to breed with one another. In addition, it resulted in a free exchange of ideas, and Europe began a slow process of change. People gradually moved from a life of hunting and gathering in small groups, to living in settled villages and raising crops.

One of the earliest settled communities in Europe was at Lepenski Vir in the former Yugoslavia. Today, it is located in Eastern Serbia, and the archaeological evidence of this early civilization closely corresponds with the genetic fingerprint of the I1b haplogroup. Lepenski Vir became a settled community about 8,500 years ago, and it was comprised of approximately 60 permanent homes that were built along the banks of the Danube River.

Archaeological excavations reveal that each of these homes housed characteristic stone carvings of “fish gods”. It is believed that the Danube provided these people with much of their food, but the remains of homes built of stone and wood indicates that they were among Europe’s earliest farming communities.

In reality, Lepenski Vir was only one of many farming communities that sprang up along the Danube River during the Mesolithic period otherwise known as the Middle Stone Age. Residents of this settlement traded pottery and food with neighboring communities. Over time, however, Lepenski Vir came to be the ritual center for what would become known as the Starcevo-Cris Culture.

This ancient culture overlapped the ancestral home of haplogroup I1b which had become established in the Balkan region many thousands of years earlier. Moreover, Starcevo culture appears to have been somewhat of an outgrowth of the earlier Gravettian culture. Perhaps the most notable similarity connecting the two ancient cultures is the continued obsession with fertility demonstrated in “Venus figurines”. A website pertaining to this early farming culture has been found at Ancient.

It is noted that “The Starcevo Culture covered a huge area, including today’s Slovakia, western Ukraine, Romania, eastern Hungary, Bulgaria, Serbia, and northeast Bosnia. In Croatia, it extended at least as far as Vucedol (near Vukovar) and Sarvas (near Osijek)”.

Archaeological findings in the surrounding area show evidence of temporary settlements, probably built for the purpose of hunting and gathering of food or raw materials. This suggests a complex semi-nomadic economy with managed exploitation of resources in the area not immediately surrounding the village, something remarkable for the traditional view of Mesolithic people of Europe. More complexity in an economy leads to professional specialization and thus to social differentiation.

This is clearly evident in the layout of the Lepenski Vir Ia-e settlement. The village is well planned. All houses are built according to one complex geometric pattern. These remains of houses constitute the distinct Lepenski Vir architecture, one of the important achievements of this culture. The main layout of the village is clearly visible. The dead were buried outside the village in an elaborate cemetery. The only exceptions were apparently a few notable elders who were buried behind the fireplaces in houses, according to a religious ritual.

The complex social structure was dominated by a religion which probably served as a binding force for the community and a means of coordination of activity for its members. Numerous sacral objects that were discovered in this layer support this theory. The most remarkable examples are piscine sculptures, unique to the Lepenski Vir culture, which represent one of the first examples of monumental sacral art on European soil.

The Lepenski Vir culture was a fascinating prehistoric culture in Europe. They lived a pretty sedentary lifestyle compared to their contemporaries. The group seems to have migrated from present day Czech Republic and settled along the banks of the Danube in today’s Serbia. They became a river people. They built their houses by the river. They fished the river. And they began to worship the river.

The Lepenski Vir culture was advanced for its time. They planned their villages in an organized way. Their houses were built using advanced techniques. Once they had their houses built and their fish done fished they turned to religion. They created a fairly complex religion. The evidence comes from a lavish grave site outside of the village, ceremonial burials of what appear to be elders in the fireplaces of some homes, and the sculptures. The sculptures are crosses between humans and fish.

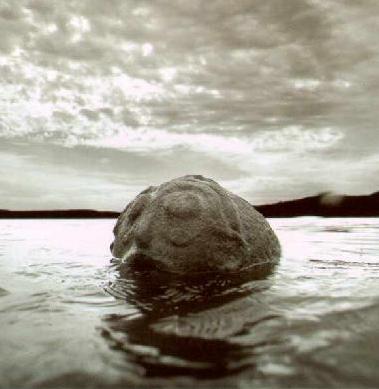

The earliest sculptures found on the site date to the time of Lepenski Vir Ib settlement. They are present in all the following layers until the end of the distinct Lepenski vir culture. All the sculptures were carved from round sandstone cobbles found on the river banks.

The sculptures can be separated in two distinct categories, one with simple geometric patterns and the other representing humanoid figures. The latter are the most interesting. All of these figural sculptures were modeled in a naturalistic and strongly expressionistic manner. Only the head and face of the human figures were modeled realistically, with strong brow arches, an elongated nose, and a wide, fish-like mouth.

Hair, beard, arms and hands can be seen on some of the figures in a stylized form. Many fish-like features can be noticed. Along with the position which these sculptures had in the house shrine, they suggest a connection with river gods.

Lepenski Vir – a Mesolithic site on the Iron Gates Gorge of the Danube

Ertebølle and Lepenski Vir at the Neolithic frontier

A Remarkable Message on History

Prehistoric sites in Serbia – Wikipedia

Enki and Adapa – Sumer

Enki and later Ea were apparently depicted, sometimes, like Adam, as a man covered with the skin of a fish, and this representation, as likewise the name of his temple E-apsu, “house of the watery deep”, points decidedly to his original character as a god of the waters.

Around the excavation of the 18 shrines found on the spot, thousands of carp bones were found, consumed possibly in feasts to the god. Of his cult at Eridu, which goes back to the oldest period of Mesopotamian history, nothing definite is known except that his temple was also associated with Ninhursag’s temple which was called Esaggila, “the lofty head house” (E, house, sag, head, ila, high; or Akkadian goddess = Ila), a name shared with Marduk’s temple in Babylon, pointing to a staged tower or ziggurat (as with the temple of Enlil at Nippur, which was known as E-kur (kur, hill)), and that incantations, involving ceremonial rites in which water as a sacred element played a prominent part, formed a feature of his worship.

This seems also implicated in the epic of the hieros gamos or sacred marriage of Enki and Ninhursag (above), which seems an etiological myth of the fertilisation of the dry ground by the coming of irrigation water (from Sumerian a, ab, water or semen).

The early inscriptions of Urukagina in fact go so far as to suggest that the divine pair, Enki and Ninki, were the progenators of seven pairs of gods, including Enki as god of Eridu, Enlil of Nippur, and Su’en (or Sin) of Ur, and were themselves the children of An (sky, heaven) and Ki (earth).

The pool of the Abzu at the front of his temple was adopted also at the temple to Nanna (Akkadian Sin) the Moon, at Ur, and spread from there throughout the Middle East. It is believed to remain today as the sacred pool at Mosques, or as the holy water font in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.

Whether Eridu at one time also played an important political role in Sumerian affairs is not certain, though not improbable. At all events the prominence of “Ea” led, as in the case of Nippur, to the survival of Eridu as a sacred city, long after it had ceased to have any significance as a political center. Myths in which Ea figures prominently have been found in Assurbanipal’s library, and in the Hattusas archive in Hittite Anatolia.

As Ea, Enki had a wide influence outside of Sumer, being equated with El (at Ugarit) and possibly Yah (at Ebla) in the Canaanite ‘ilhm pantheon, he is also found in Hurrian and Hittite mythology, as a god of contracts, and is particularly favourable to humankind. Amongst the Western Semites, it is thought that Ea was equated to the term *hyy (life), referring to Enki’s waters as life giving. Enki/Ea is essentially a god of civilization, wisdom, and culture. He was also the creator and protector of man, and of the world in general.

Traces of this view appear in the Marduk epic celebrating the achievements of this god and the close connection between the Ea cult at Eridu and that of Marduk. The correlation between the two rises from two other important connections: (1) that the name of Marduk’s sanctuary at Babylon bears the same name, Esaggila, as that of a temple in Eridu, and (2) that Marduk is generally termed the son of Ea, who derives his powers from the voluntary abdication of the father in favour of his son.

Accordingly, the incantations originally composed for the Ea cult were re-edited by the priests of Babylon and adapted to the worship of Marduk, and, similarly, the hymns to Marduk betray traces of the transfer to Marduk of attributes which originally belonged to Ea.

It is, however, as the third figure in the triad (the two other members of which were Anu and Enlil) that Ea acquires his permanent place in the pantheon. To him was assigned the control of the watery element, and in this capacity he becomes the shar apsi; i.e. king of the Apsu or “the deep”.

The Apsu was figured as the abyss of water beneath the earth, and since the gathering place of the dead, known as Aralu, was situated near the confines of the Apsu, he was also designated as En-Ki; i.e. “lord of that which is below”, in contrast to Anu, who was the lord of the “above” or the heavens.

The cult of Ea extended throughout Babylonia and Assyria. We find temples and shrines erected in his honour, e.g. at Nippur, Girsu, Ur, Babylon, Sippar, and Nineveh, and the numerous epithets given to him, as well as the various forms under which the god appears, alike bear witness to the popularity which he enjoyed from the earliest to the latest period of Babylonian-Assyrian history.

The consort of Ea, known as Ninhursag, Ki, Uriash Damkina, “lady of that which is below”, or Damgalnunna, “big lady of the waters”, originally was fully equal with Ea, but in more patriarchal Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times plays a part merely in association with her lord.

Generally, however, Enki seems to be a reflection of pre-patriarchal times, in which relations between the sexes were characterised by a situation of greater gender equality. In his character, he prefers persuasion to conflict, which he seeks to avoid if possible.

Vishaps – Armenia

The unique monuments of prehistoric Armenia, XE “višap” vishaps (Arm. višap ‘serpent, dragon’ an Iranian borrwing) or “dragon stones” are spread in many provinces of historical Armenia – Gegharkunik, Aragatsotn, Javakhk, Tayk, etc. They are cigar-shaped huge stones, 10-20 feet tall, usually situated in the mountains, near the sources of rivers and lakes.

Many of them are in the shape of fish; they have a bull’s skin (complete with head and feet) carved into them; there is also a stream of water flowing from the mouth of the bull’s skin and some vishaps have images of water birds carved below the bull’s head. The earliest višap XE “višap” stelae would be dated, probably, from the 18th-16th centuries BC; an Urartian inscription in a višap from Garni testifies that they were created in pre-Urartian times (before the 8th century BC).

Vishapakar, The Unique Megaliths of the Armenian Plateau

Filed under: Uncategorized