Scorpions and Rosette

Steatite, Stamp seal, North Mesopotamia, Gawra period, c.3300 BC

Cult scene: the worship of the sun-god, Shamash. Limestone cylinder-seal, Mesopotamia

Ram in a Thicket, Ur, Southern Iraq, 2600-2400 BC

Puabi (Akkadian: “Word of my father”), Ur, during the First Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2600 BCE)

Queen Pu-abi’s attendants, who were sacrificed to serve her in the afterlife

A shell plaque found in Queen Pu-abi’s tomb

- It shows ibexes rearing up on their hind legs to feed on the leaves of a high branch.

Note the eight-pointed rosette in the cente

Scorpion macehead

Narmer Palette

Rosette designs from Meyer’s Handbook of Ornament

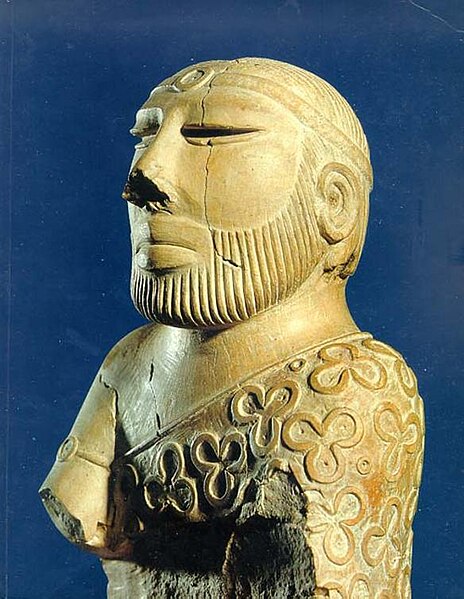

Mohenjo-daro Priest

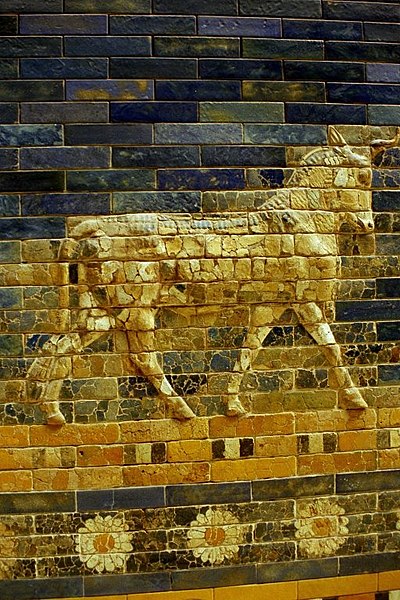

Sitting bull

- Black marble (formerly inlaid), found in Warka (ancient city of Uruk), Djemdet-Nasr period (ca. 3000 BC)

Mycenaean Jug

Phaistos Disc, Phaistos, Minoan Crete, ca. 1700 BC

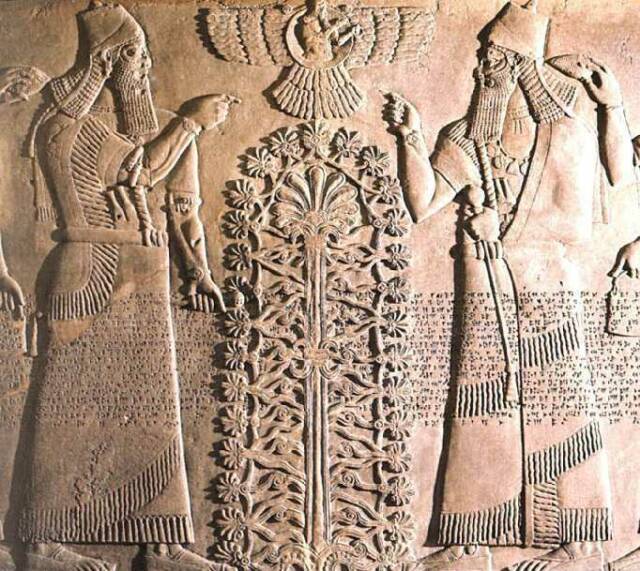

Assyrian Tree of Life

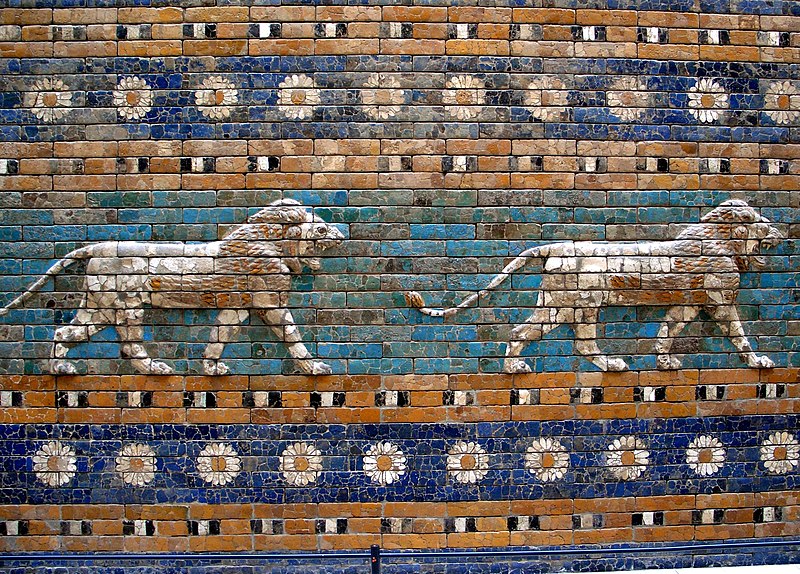

The Ishtar Gate, Babylon, 575 BC

Rosette design at the bottom of a statue of the Buddha, Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, circa 1st century CE

A rosette is a round, stylized flower design, used extensively in sculptural objects from antiquity. Appearing in Mesopotamia and used to decorate the funeral stele in Ancient Greece. Adopted later in Romaneseque and Renaissance, and also common in the art of Central Asia, spreading as far as India where it is used as a decorative motif in Greco-Buddhist art.

The rosette derives from the natural shape of a rosette in botany, formed by leaves radiating out from the stem of a plant and visible even after the flowers have withered. The formalised flower motif is often in carved in stone or wood to create decorative ornaments for architecture and furniture. It was a common motif in metalworking, jewelry design and the applied arts at the intersection of two materials, or to form a decorative border.

This motif was widespread throughout Europe and the Near East. Rosette decorations have been used for formal military awards. They are also used to decorate musical instruments, such as around the perimeter of sound holes of guitars.

One of the earliest appearances of the rosette in ancient art is in early fourth millennium BC Mesopotamia. It’s not know for certain what particular symbolism the Sumerians attached to the eight-pointed rosette, but it occurs throughout their cultural history. It can be seen on shell plaques, on the headdresses, and on many other artifacts.

Inanna’s symbol is an eight-pointed star or a rosette. She was associated with lions – even then a symbol of power – and was frequently depicted standing on the backs of two lionesses. Her cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds, representing the doorpost of the storehouse (and thus fertility and plenty).

Inanna was associated with the celestial planet Venus. There are hymns to Inanna as her astral manifestation. It also is believed that in many myths about Inanna, including Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld and Inanna and Shukaletuda, her movements correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.

Also, because of its positioning so close to Earth, Venus moves rather irregularly across the sky, and never travels all the way across the dome of the sky as most celestial bodies do, instead, Venus rises in the East and the West in both the morning and evening.

Because of Venus’ erratic movements (it disappears behind the sun from 90–3 days at a time and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as single entity, but rather two separate stars on each horizon as the morning and evening star.

The Mesopotamians, however, most likely understood that the planet was one entity. A cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period expresses the knowledge that both morning and evening stars were the same celestial entity.

The erratic movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna’s erratic nature. Like Venus, Inanna seems unpredictable in her actions, being both the goddess of love and war, having both masculine and feminine qualities, and occasionally having temper tantrums. However, Mesopotamian literature takes this comparison one step further, explaining Inanna’s physical movements in mythology as similar to the movements of Venus in the sky.

Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld explains how Inanna is able to, unlike any other deity, descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East.

In Inanna and Shukaletuda, in search of her attacker, Inanna makes several movements throughout the myth that correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky. An introductory hymn explains Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be, the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West. Shukaletuda also is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly to the eastern and western horizons.

Inanna was associated with the eastern fish of the last of the zodiacal constellations, Pisces. Her consort Dumuzi was associated with the contiguous first constellation, Aries.

Seal impressions from the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3100–2900 BC) show a fixed sequence of city symbols including those of Ur, Larsa, Zabalam, Urum, Arina, and probably Kesh. It is likely that this list reflects the report of contributions to Inanna at Uruk from cities supporting her cult.

A large number of similar sealings were found from the slightly later Early Dynastic I phase at Ur, in a slightly different order, combined with the rosette symbol of Inanna, that were definitely used for this purpose. They had been used to lock storerooms to preserve materials set aside for her cult. Inanna’s primary temple of worship was the Eanna, located in Uruk (c.f. Worship).

In Egypt the Scorpion macehead (also known as the Major Scorpion macehead) is a decorated ancient Egyptian macehead found by British archeologists James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green in what they called the main deposit in the temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis during the dig season of 1897/1898.

It is made of limestone, is pear-shaped, and is attributed to the Scorpion II (Ancient Egyptian: possibly Selk or Weha), also known as King Scorpion, referring to the second of two kings or chieftains of that name during the Protodynastic Period of Upper Egypt, due to the glyph of a scorpion engraved close to the image of a king wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt.

Little is left of this macehead and its imagery: A king wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, sitting on a throne below a canopy, holding a flail. Beside his head, in the upper right corner, there is a image of a scorpion and a rosette. Facing him is a falcon who may be holding an end of a rope in one of its claws – a motif also present on the Narmer Palette.

On the macehead the king sporting a bull’s tail is standing by a body of water, probably a canal, holding a hoe. He is wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt and is followed by two fan bearers. A scorpion and a rosette are depicted close to his head. He is facing a man holding a basket and men holding standards. A number of men are busy along the banks of the canal. In the rear of the king’s retinue are some plants, a group of women clapping their hands and a small group of people, all of them facing away from the king. In the top register there is a row of nome standards. A bird is dangling from each of them, strung up by its neck.

A second, smaller macehead fragment showing Scorpion wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt is referred to as the Minor Scorpion macehead. Little is left of this macehead and its imagery: A king wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, sitting on a throne below a canopy, holding a flail. Beside his head images of a scorpion and a rosette. Facing him is a falcon who may be holding an end of a rope in one of its claws – a motif also present on the Narmer Palette.

It is believed the rosette was a symbol for kingly authority. The origin of this symbolism is unknown. Other of many examples are the famous Narmer palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, created as a memorial to a victorious campaign by that early king, also carries the rosette motif.

The Narmer Palette is a significant Egyptian archeological find, dating from about the 31st century BC, containing some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever found. It is thought by some to depict the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the king Narmer.

On one side, the king is depicted with the bulbed White Crown of Upper (southern) Egypt, and the other side depicts the king wearing the level Red Crown of Lower (northern) Egypt.

A large picture in the center of the Palette depicts Narmer wielding a mace wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt (whose symbol was the flowering lotus). To his left is a man bearing the king’s sandals, once again flanked by a rosette symbol.

Along with the Scorpion Macehead and the Narmer Maceheads, also found together in the Main Deposit at Nekhen, the Narmer Palette provides one of the earliest known depictions of an Egyptian king.

The Palette shows many of the classic conventions of Ancient Egyptian art, which must already have been formalized by the time of the Palette’s creation. The Egyptologist Bob Brier has referred to the Narmer Palette as “the first historical document in the world”.

The Palette, which has survived five millennia in almost perfect condition, was discovered by British archeologists James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green, in what they called the Main Deposit in the Temple of Horus at Nekhen, during the dig season of 1897–1898. Also found at this dig were the Narmer Macehead and the Scorpion Macehead.

The exact place and circumstances of these finds were not recorded very clearly by Quibell and Green. In fact, Green’s report placed the Palette in a different layer one or two yards away from the deposit, which is considered to be more accurate on the basis of the original excavation notes.

It has been suggested that these objects were royal donations made to the temple. Nekhen, or Hierakonpolis, was the ancient capital of Upper Egypt during the pre-dynastic Naqada III phase of Egyptian history.

Palettes were typically used for grinding cosmetics, but this palette is too large and heavy (and elaborate) to have been created for personal use and was probably a ritual or votive object, specifically made for donation to, or use in, a temple. One theory is that it was used to grind cosmetics to adorn the statues of the gods.

The rosette continued to have a royal symbolism of dignity and authority down into later times. A Hittite tomb stela from the 8th century BC portrays a wonderful example of this symbol hovering over a princess and her attendant. What appears to be a sun-disk contains an eight-pointed rosette with two highly detailed and very bird-like wings stretching out on either side. A light gray steatite Hittite spool seal dating from 1500 BC has a stag on one side and a rosette on the other. The seal is drilled in the center of each.

Another early Mediterranean occurrence of the rosette design derives from Minoan Crete; for example, the rosette design has been found on the famed Phaistos Disc, recovered from the Phaistos archaeological site in southern Crete.

Its purpose and meaning, and even its original geographical place of manufacture, remain disputed, making it one of the most famous mysteries of archaeology. It is made of clay and now is on display at the Archaeological Museum of Herakleion. The exact date of manufacture is uncertain; some archaeologists ascribe it to the 17th century BC.

The Phaistos Disc captured the imagination of amateur and professional archeologists, and many attempts have been made to decipher the code behind the disc’s signs. While it is not clear that it is a script, most attempted decipherments assume that it is; most additionally assume a syllabary, others an alphabet or logography.

Attempts at decipherment are generally thought to be unlikely to succeed unless more examples of the signs are found, as it is generally agreed that there is not enough context available for a meaningful analysis.

The Phaistos disk was found in 1908 in a building at the Minoan palace site of Phaistos, near Hagia Triada, on the south coast of Crete. The disk is 16 centimeters in diameter (or 6 inches, approximately the size of the palm of your hand). It is about 15 cm (5.9 in) in diameter and covered on both sides with a spiral of stamped symbols.

Many, including Benjamin Schwartz, who in his work on decipherment refers to the Phaistos Disc as “the first movable type”, regard it as the first example of printing, since the embedded impressions (figures) were placed there by some form of prepared punch. How such symbolic tools were used otherwise is unknown, since similar examples have never been discovered.

In his popular science book Guns, Germs and Steel, Jared Diamond describes the disc as an example of a technological advancement that did not become widespread because it was made at the wrong time in history, and contrasts this with Gutenberg’s printing press.

The inscription was apparently made by pressing pre-formed hieroglyphic “seals” into the soft clay, in a clockwise sequence spiraling towards the disc’s center. It was then fired at high temperature. The unique character of the Phaistos Disc stems from the fact that the entire text was inscribed in this way, reproducing a body of text with reusable characters.

The German typesetter and linguist Herbert Brekle, in his article “The typographic principle” in the Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, argues that the Phaistos Disc is an early document of movable type printing, since it meets the essential criteria of typographic printing, that of type identity:

An early clear incidence for the realization of the typographic principle is the notorious Phaistos Disc (ca. 1800–1600 BC). If the disc is, as assumed, a textual representation, we are really dealing with a “printed” text, which fulfills all definitional criteria of the typographic principle.

The spiral sequencing of the graphematical units, the fact that they are impressed in a clay disc (blind printing!) and not imprinted are merely possible technological variants of textual representation. The decisive factor is that the material “types” are proven to be repeatedly instantiated on the clay disc.

Eight-petaled rosettes similar to those on the Disk and on the various ancient gameboards appeared also on many other objects. They were generally a symbol for the sun, or more precisely its cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and so indicated the passages from one state of existence into another.

We might question the origin of the rosette images. Consider an eight-leaf rosette carved through an ivory disk from a child’s burial at the European Gravettian burial site in Sungir, situated about 200 km east of Moscow, on the outskirts of Vladimir, near the Klyazma River in Russia, dated to about 28,000 years ago, the earliest example found up to now, and one of the most beautiful. Clearly the rosette has a very old history, dating back to the times of the Cave Paintings of Europe, and the Great Flood, or earlier.

It was found in a child’s burial at the site, and its funerary context suggests that it may have been associated with the rebirth- and- renewal cluster of ideas already back then.

Whatever this rosette may have meant to its maker, its pierced design evokes to modern eyes the concept of “passage” or “transition” through its central opening even more powerfully than any flat shape could.

Closer to us in time, and less open to doubt about its meaning, are the many ancient Egyptian pictures that show the young sun god being born in a lotus blossom with eight leaves. This image reflects a sunrise over the flooded lands of the Delta where lotus, which grows as the Nile rises, covered the waters to the horizon. It was therefore a fitting sign for that daily rebirth and new beginning.

On the other hand, the association of that flower with birth was not unique to Egypt because in India, various gods, and particularly the Buddha, also emerged into the world from that same eight-petaled lotus.

The Egyptian “Book of the Dead” calls the king of the gods Re in Chapter 15 “the golden youth who came forth from the lotus”, and in Chapter 81 the deceased utters the desire to be transformed into a sacred lotus2.

The typical copy of that book also included a vignette of the cow-headed sky-goddess Hathor, the “mother of light”, emerging from the burial mound with an eight-leaved rosette on her neck. Right next to her, the tomb owner rises from his coffin and clutches two “Life” signs in his hands, leaving no doubt about the meaning of the scene.

Similarly, a painted portrait from Tutankhamun’s tomb shows him rising out of a lotus blossom with eight petals that grows from his coffin and so illustrates his resurrection.

Such images led the symbolist Manfred Lurker to propose in his illustrated Dictionary “The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt” that the rosette represented the sun breaking forth after the night and the defeat of the abysmal darkness.

The Bronze Age Cretans, too, decorated many objects with eight-leaved rosettes, including the ceiling of the “Throne Room” in the palace at Knossos. Like the later Philistines and Canaanites, they used that rosette as one of their favorite pottery ornaments.

The presence of golden eight-leaf rosettes in tombs at Mochlos, Crete, from around 2,000 BCE, and in Mycenaean graves from more than half a millennium later, attests that in these cultures, too, this sign was associated with a symbolism of death to be followed by rebirth.

Some of the wigs on the human-shaped clay coffins from Philistine-occupied Beth-Shean bear lotus flowers, and the sarcophagus of king Ahiram from the Phoenician city of Byblos, dated to about the time of Solomon, displays a ceremonial scene common in Phoenician art which shows him holding a lotus flower as a sign of his rebirth and apotheosis.

The Classical Greeks were equally fond of the eight-leaved rosette motif. One particularly revealing stone sculpture at the former site of the Eleusinian mystery cult shows an initiate emerging from the center of a giant eight-petaled flower bud that is marked all over with eight-leaf rosettes. The context leaves here no doubt that this sculpture illustrated the spiritual rebirth which the initiate to those mysteries was said to achieve7.

In the sun cults of ancient Northern Europe, a wheel with eight spokes represented the sun and its regenerative powers but appeared also as a symbol of death and destruction.

Similarly, the symbolic meaning of the Near Eastern rosette included death, as on a fragment from the throne of pharaoh Thutmosis IV where that sign marks an enemy crushed by the king’s foot.

On Greek vase paintings of battles, or of Theseus killing the Minotaur, an eight-leaf rosette often conveyed that the combat ended in death. For instance, a vase painting from about 660 BCE shows a clash between the warriors on two ships. Where their spears meet over the opposing bows, the ancient painter placed the eight-leaf rosette the way a modern comic book artist would put there a graphically enhanced “Zap” or “Pow”.

In Minotaur-slaying scenes, the rosette marks sometimes that monster to announce its upcoming death. At other times, it decorates Theseus and can be seen as a sign that he will return from his excursion into the labyrinth, a symbol of the underworld, and will thereby be regenerated.

In India, and in a few cases also in ancient Mesopotamia, an eight- leaf rosette adorned the memorial stelae of widow- burning victims who had been killed in their husbands’ funeral pyres.

In general, the contexts in which we find the eight-leaf rosette suggest that it represented the birth, death, and rebirth of the sun (and/or of the planet Venus), in many of the ancient Near Eastern religions which could have influenced the maker of the Disk.

This direction-reversing track on each side of the Disk resembles the paths on a group of gameboards for race games from India. These also begin with a counterclockwise tour around the border of their board and then make a U-turn to spiral clockwise to the center.

A geographical distance like that between India and Crete does not rule out the possibility of faraway connections through which people far from each other often shared common symbols or their expressions such as, for instance, this unique and characteristic game path of a counterclockwise outer turn followed by a clockwise spiral inward.

India was an active part of the same cultural complex that produced the civilizations of the Fertile Crescent and their many common basic beliefs. The people of the Indus Valley, or Harappan, civilization shared a common cultural matrix with the Cretans and many other peoples of their time. That matrix included, for instance, bull cults and snake worship which are both attested in both India and Crete and in some of the areas between them.

In addition, both emphasized maritime trade since Crete is an island, and practically all the Harappan cities were built on the seashore or on navigable rivers. The ruins of Harappa and of Knossos also happened to reveal some of the most advanced sanitary plumbing systems of their time.

There can be no doubt about the existence of ancient trading contacts between Bronze Age Crete and Harappan India, however indirect these may have been through middlemen from Mari or elsewhere. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who excavated many of the principal Indus Valley sites, points out that two segmented faience beads, one from Knossos and the other from Harappa, did not only have the same shape but were also identical in composition, as shown by spectrographic analysis25.

Despite the miles and mountains that separated those civilizations, many of their beliefs spread also among them. For instance, Indian Vedic gods such as Mitra, Varuna, and Indra witnessed the oaths of kings in Hurrian Mitanni which is now in Syria. Also, most of the Hurrian words for horse craft were derived from Sanskrit, a major language of ancient India.

Moreover, in Ugarit on the Syrian coast, one of the words for “fire” was the name of Agni, the Indian Vedic god of fire who led to Latin “ignis” and so provided English speakers with “ignition” as well as the cozy “inglenook” by the fireplace.

As another example of such wide diffusion for certain ideas, the Classical Labyrinth design with seven circuits is first attested in the above doodle on the back of a book-keeping tablet from Pylos in Greece, dated to about 1200 BCE.

This labyrinth was also strongly associated with nearby Crete where it appeared in both round and square forms on coins from about the sixth century BCE on. However, that same intricate and unmistakable design is also reported from early southern India, among many other times and places.

Similarly, board games travel easily and spread widely, like most other number-related traditions, and they are often found distributed in almost identical form over large regions or in widely separated areas.

An excellent example is the ancient game of “Five Lines” which is still played in Crete and, of all other places, also in Northern India. A board for this game, shaped like a five-pointed star, was also found chiseled into the roofing slabs of a temple at Kurna in Egypt, completed during the 14th century BCE.

It takes therefore no stretch of the imagination to suspect possible relationships between board games played in distant areas of the same cultural complex, particularly if these share an otherwise unusual trait such as that U-turn after the first counterclockwise go-around.

Graves 1 and 2 at Sunghir are described as “the most spectacular” among burials. The adult male was buried in what is called Grave 1 and the two adolescent children in Grave 2, placed head to head, together with an adult femur filled with red ochre.

The settlement area was found to have four burials: the remains of an older man and two adolescent children are particularly well-preserved, and the nature of the rich and extensive burial goods suggests they belonged to the same class. In addition, a skull and two fragments of human femur were also found at the settlement area, and two human skeletons outside the settlement area without cultural remains.

The three individuals buried at Sungir were all adorned with elaborate grave goods that included ivory-beaded jewelry, clothing, and spears. More than 13,000 beads were found (which would have taken 10,000 hours to produce). Red ochre, an important ritual material associated with burials at this time, covered the burials.

The children are considered a twin burial, thought to have ritual purpose, likely sacrifice. The findings of such complete skeletons are rare in late Stone Age, and indicate the high status of the male adult and related children. The children had the same MtDNA, which may indicate the same maternal lineage, but more would need to be known about other individuals in the settlement.

The site is one of the earliest examples of ritual burials and constitutes important evidence of the antiquity of human religious practices. The extraordinary collection of grave goods, the position of the bodies, and other factors all indicate it was a burial of high importance. Two other remains at the site are partial skeletons.

The remains are held by the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of RAS, Moscow. In 2004, the International Seminar, “Upper Paleolithic People from Sunghir, Russia,” was hosted by the Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, UK. It is the second of two major conferences about this site.

Two books have been published in Moscow about the findings. Upper Palaeolithic Site Sungir (graves and environment) (1998) was the first complete publication about the site, including an inventory of artifacts, reconstruction of the Paleolithic man’s clothes, archaic counting and calendar. The second part of the book displays the reconstruction of the environment by geological, palinological, zoological data.

The second book, Homo Sungirensis (2000) edited by T.I. Aexeeva et al., includes articles published since the first book, and new anthropological data derived from morphology, palaeopathology, X-ray study, histology, trace elements and molecular genetic analyses. It has an illustrated catalogue of all the skeletal materials.

Sungir – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rosettes of the Tree of Life around the Second Garden

Tree of Life in Crete and Cyprus

Rosettes of the Tree of Life in Crete and Cyprus

Tree of Life around the Second Garden

Rosettes of the Tree of Life around the Second Garden

Tree of Life around Lake Van and Mount Ararat

Rosettes of the Tree of Life around Lake Van and Mount Ararat

Rosettes of the Tree of Life in Persia

Filed under: Uncategorized