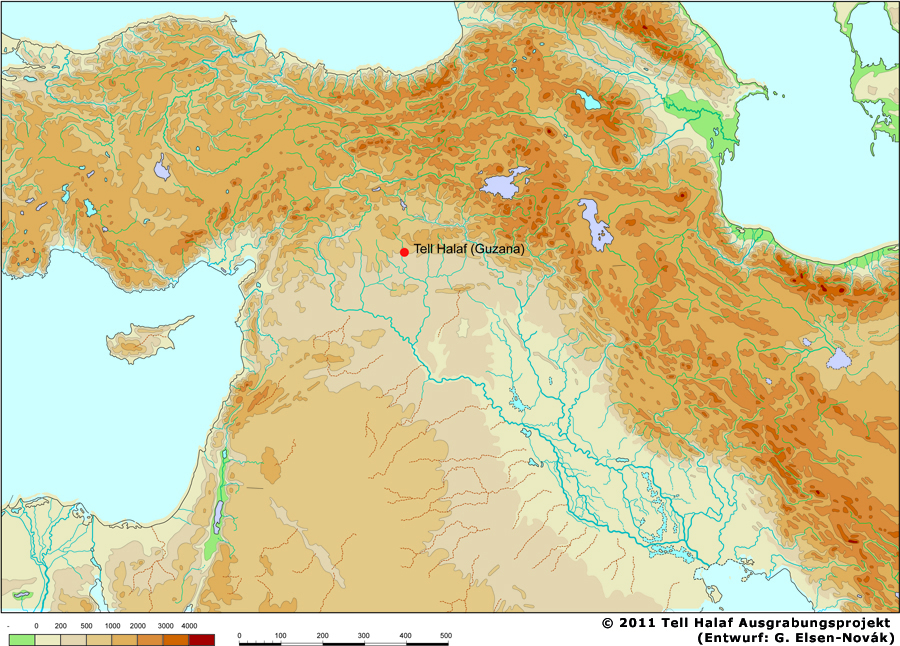

In the period 6500–5500 B.C., a farming society emerged in northern Mesopotamia and Syria which shared a common culture and produced pottery that is among the finest ever made in the Near East. This culture is known as Halaf, after the site of Tell Halaf in northeastern Syria where it was first identified.

The Halaf potters used different sources of clay from their neighbors and achieved outstanding elaboration and elegance of design with their superior quality ware. Some of the most beautifully painted polychrome ceramics were produced toward the end of the Halaf period. This distinctive pottery has been found from southeastern Turkey to Iran, but may have its origins in the region of the River Khabur (modern Syria).

The Halaf culture, which lasted between about 6100 and 5500 BC., is a continuous development out of the earlier Pottery Neolithic and is located primarily in south-eastern Turkey, Syria, and northern Iraq, although Halaf-influenced material is found throughout Greater Mesopotamia.

The term «Proto-Halaf period» refers to the gradual emergence of the Halaf culture. It reformulates the «Halafcultural package» as this has been traditionally understood, and it shows that the Halaf emerged rapidly, but gradually, at the end oftheseventh millennium cal BC. The term refers to a distinct ceramic assemblage characterised by the introduction of painted Fine Ware within the later Pre-Halafceramic assemblage. Although these new wares represent changes in ceramic technology and production, other cultural aspects continue without abrupt change.

The recent discoveries at various Late Neolithic sites in Syrian and elsewhere that have been reviews here are really changing the old, traditional schemes, which often presupposed abrupt transitions from one culture-historical entity to another. At present, there is growing evidence for considerable continuity during the seventh and sixth millennium BC.

At the northern Syrian sites, where theProto-Halaf stage was first defined,there is no perceptible break and at several sites (Tell Sabi Abyad, Tell Halula) the Proto-Halafceramic assemblage appears tobe closely linked to the preceding late Pre-Halaf. The key evidence for the Proto-Halaf period is the appearance of new ceramic categories that did not existed before, manufactured according to high technological standards and complexly decorated.

The similarities ofthese new painted wares from one Proto-Halafsiteto another points to strong relationships between different communities. On the other hand, the evidence oflocal variety in ceramic production would indicate acertain level of independence of local groups.

Although this new stage deservesto be studied much more, it appears to be the case that apart from the ceramicsmost other aspects of the material culture show a gradual, not abrupt evolution from the precedent stage, such as the production of lithic tools, property markers such as stamp seals, the architecture and burial practices.

The discovery of Proto-Halaf layers at Tell Halula, Tell Sabi Abyad and Tell Chagar Bazar has added much insight into the origins of the Halaf and its initial development, and shows that the Halaf resulted from a gradual, continuous process of cultural change. It also seems to be clear that the origins of the Halaf were regionally heterogeneous.

The Halaf culture as it is traditionally understood appears to have evolved over a very large area, which comprises the Euphrates valley (until recently considered to be a peripheral area), the Balikh valley and the Khabur in Syria but also northern Iraq, southern Turkey and the Upper Tigris area.

Hassuna or Tell Hassuna is an ancient Mesopotamian site situated in what was to become ancient Assyria, and is now in the Ninawa Governorate of Iraq west of the Tigris river, south of Mosul and about 35 km southwest of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh.

By around 6000 BC people had moved into the foothills (piedmont) of northernmost Mesopotamia where there was enough rainfall to allow for “dry” agriculture in some places. These were the first farmers in northernmost Mesopotamia. They made Hassuna style pottery (cream slip with reddish paint in linear designs). Hassuna people lived in small villages or hamlets ranging from 2 to 8 acres (32,000 m2).

At Tell Hassuna, adobe dwellings built around open central courts with fine painted pottery replace earlier levels with crude pottery. Hand axes, sickles, grinding stones, bins, baking ovens and numerous bones of domesticated animals reflect settled agricultural life. Female figurines have been related to worship and jar burials within which food was placed related to belief in afterlife. The relationship of Hassuna pottery to that of Jericho suggests that village culture was becoming widespread.

Shulaveri-Shomu culture is a Late Neolithic/Eneolithic culture that existed on the territory of present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Armenian Highlands. The culture is dated to mid-6th or early-5th millennia BC and is thought to be one of the earliest known Neolithic cultures. The Shulaveri-Shomu culture begins after the 8.2 kiloyear event which was a sudden decrease in global temperatures starting ca. 6200 BC and which lasted for about two to four centuries.

Shulaveri culture predates the Kura-Araxes culture and surrounding areas, which is assigned to the period of ca. 4000 – 2200 BC, and had close relation with the middle Bronze Age culture called Trialeti culture (ca. 3000 – 1500 BC).[3] Sioni culture of Eastern Georgia possibly represents a transition from the Shulaveri to the Kura-Arax cultural complex.

In around ca. 6000–4200 B.C the Shulaveri-Shomu and other Neolithic/Chalcolithic cultures of the Southern Caucasus use local obsidian for tools, raise animals such as cattle and pigs, and grow crops, including grapes. Many of the characteristic traits of the Shulaverian material culture (circular mudbrick architecture, pottery decorated by plastic design, anthropomorphic female figurines, obsidian industry with an emphasis on production of long prismatic blades) are believed to have their origin in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Hassuna, Halaf).

The Halaf period was succeeded by the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period (~5500 – 5200 cal. BCE) and then by the Ubaid period (~5200 – 4000 cal. BCE). The Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period (ca. 5500/5400 to 5200/5000 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. It lies chronologically between the Halaf period and the Ubaid period. It is a very poorly understood period and was created to explain the gradual change from Halaf style pottery to Ubaid style pottery in North Mesopotamia.

Archaeology Archaeologically the period is defined more by absence then data as the Halaf appears to have ended before 5500/5400 cal. BC and the Ubaid begins after 5200 cal. BC. There are only two sites that run from the Halaf until the Ubaid. The first of these, Tepe Gawra, was excavated in the 1930s when stratigraphic controls were lacking and it is difficult to re-create the sequence. The second, Tell Aqab remains largely unpublished.

This makes definitive statements about the period difficult and with the present state of archaeological knowledge nothing certain can be claimed about the Halaf-Ubaid transitional except that it is a couple of hundred years long and pottery styles changed over the period.

The Ubaid period (ca. 6500 to 3800 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from the tell (mound) of al-`Ubaid west of nearby Ur in southern Iraq’s Dhi Qar Governorate where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvium although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.

In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughoutMesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. During this time, the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was established at Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI), ca. 5300 BC, by farmers who brought with them the Hadji Muhammed culture, which first pioneered irrigation agriculture. It appears this culture was derived from the Samarran culture from northern Mesopotamia.

The Samarran Culture is primarily known for its finely-made pottery decorated against dark-fired backgrounds with stylized figures of animals and birds and geometric designs. This widely-exported type of pottery, one of the first widespread, relatively uniform pottery styles in the Ancient Near East, was first recognized at Samarra. The Samarran Culture was the precursor to the Mesopotamian culture of the Ubaid period.

Hadji Muhammed was a small village in Southern Iraq which gives its name to a style of painted pottery and the early phase of what is the Ubaid culture. The pottery is painted in dark brown, black or purple in an attractive geometric style. Sandwiched between the earliest settlement of Eridu and the later “classical” Ubaid style, the culture is found as far north as Ras Al-Amiya. The Hadji Muhammed period saw the development of extensive canal networks from major settlements.

Irrigation agriculture, which seem to have developed first at Choga Mami (4700–4600 BC), a Samarra ware archaeological site of Southern Iraq in the Mandali region which shows the first canal irrigation in operation at about 6000 BCE, and rapidly spread elsewhere, from the first required collective effort and centralised coordination of labour. Buildings were of wattle and daub or mud brick.

Joan Oates has suggested on the basis of continuity in configurations of certain vessels, despite differences in thickness of others that it is just a difference in style, rather than a new cultural tradition.

It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. Eridu remained an important religious center when it was gradually surpassed in size by the nearby city of Uruk. The story of the passing of the me (gifts of civilisation) to Inanna, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect this shift in hegemony.

It appears that this early culture was an amalgam of three distinct cultural influences: peasant farmers, living in wattle and daub or clay brick houses and practicing irrigation agriculture; hunter-fishermen living in woven reed houses and living on floating islands in the marshes (Proto-Sumerians); and Proto-Akkadian nomadic pastoralists, living in black tents.

Sumer (from Akkadian Šumeru; Sumerian ki-en-ĝir, approximately “land of the civilized kings” or “native land”) was an ancient civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq, during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age.

Although the earliest historical records in the region do not go back much further than ca. 2900 BC, modern historians have asserted that Sumer was first settled between ca. 4500 and 4000 BC by a non-Semitic people who may or may not have spoken the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc. as evidence).

These conjectured, prehistoric people are now called Ubaidians, and are theorized to have evolved from the Chalcolithic Samarra culture (ca 5500–4800 BC) of northern Mesopotamia (Assyria) identified at the rich site of Tell Sawwan, where evidence of irrigation—including flax—establishes the presence of a prosperous settled culture with a highly organized social structure.

The Ubaidians were the first civilizing force in Sumer, draining the marshes for agriculture, developing trade, and establishing industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery. Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods.

Sumer (from Akkadian Šumeru; Sumerian ki-en-ĝir, approximately “land of the civilized kings” or “native land”) was an ancient civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern-day southern Iraq and Kuwait, during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age.

Although the earliest forms of writing in the region do not go back much further than c. 3500 BC, modern historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled between c. 5500 and 4000 BC by a non-Semitic people who may or may not have spoken the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc. as evidence).

These conjectured, prehistoric people are now called “proto-Euphrateans” or “Ubaidians”, and are theorized to have evolved from farmers who brought with them the Hadji Muhammed culture, which first pioneered irrigation agriculture. It appears this culture was derived from the Samarran culture from northern Mesopotamia.

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. During this time, the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was established at Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI), c. 5300 BC.

It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. Eridu remained an important religious center when it was gradually surpassed in size by the nearby city of Uruk.

The story of the passing of the me (gifts of civilisation) to Inanna, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect this shift in hegemony.

It appears that this early culture was an amalgam of three distinct cultural influences: peasant farmers, living in wattle and daub or clay brick houses and practicing irrigation agriculture; hunter-fishermen living in woven reed houses and living on floating islands in the marshes (Proto-Sumerians); and Proto-Akkadian nomadic pastoralists, living in black tents.

The Ubaidians were the first civilizing force in Sumer, draining the marshes for agriculture, developing trade, and establishing industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.

However, some scholars such as Piotr Michalowski and Gerd Steiner, contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language. It has been suggested by them and others, that the Sumerian language was originally that of the hunter and fisher peoples, who lived in the marshland and the Eastern Arabia littoral region, and were part of the Arabian bifacial culture.

The Sumerian city of Eridu, on the coast of the Persian Gulf, was the world’s first city, where three separate cultures fused – that of peasant Ubaidian farmers, living in mud-brick huts and practicing irrigation; that of mobile nomadic Semitic pastoralists living in black tents and following herds of sheep and goats; and that of fisher folk, living in reed huts in the marshlands, who may have been the ancestors of the Sumerians.

Reliable historical records begin much later; there are none in Sumer of any kind that have been dated before Enmebaragesi (c. 26th century BC). Professor Juris Zarins believes the Sumerians were the people living in Eastern Arabia coast of the Persian Gulf region before it flooded at the end of the Ice Age. Sumerian literature speaks of their homeland being Dilmun.

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods. During the 3rd millennium BC, a close cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians (who spoke a language isolate) and the Semitic Akkadian speakers, which included widespread bilingualism.

The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the 3rd millennium BC as a sprachbund.

The ancient Halaf culture existed just before and during the Ubaid period at around the same time had Swastikas on their pottery and other items. These people eventually gave rise to the ancient Sumerians, who also used the Swastika symbol. The ancient Vinca culture (5500 BC) was the first appearance of the swastika in history, not what you’re reading above. The Tartaria culture of Romainia (4000 BC) had similar symbols.

Then later the Merhgarh Culture, which later became the Harappan culture of the Great Indus Valley Civilization (which is where “The Vedas” came from) also exhibited the Swastika symbolism. Then even later the legendary Xia Dynasty held the swastika symbol in high regard. Even ancient Native American Indians knew this symbol. If you’ve noticed all these cultures were exactly 1000 years apart, bringing the Swastika symbol west to east from the Balkans to China and even beyond. Look it up, do the research.

Hamoukar is a large archaeological site located in the Jazira region of northeastern Syria near the Iraqi border (Al Hasakah Governorate) and Turkey.

The Excavations have shown that this site houses the remains of one of the world’s oldest known cities, leading scholars to believe that cities in this part of the world emerged much earlier than previously thought.

Traditionally, the origins of urban developments in this part of the world have been sought in the riverine societies of southern Mesopotamia (in what is now southern Iraq). This is the area of ancient Sumer, where around 4000 BC many of the famous Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk emerged, giving this region the attributes of “Cradle of Civilization” and “Heartland of Cities.”

Following the discoveries at Hamoukar, this definition may have to extended further up the Tigris River to include that part of northern Syria where Hamoukar is located.

This archaeological discovery suggests that civilizations advanced enough to reach the size and organizational structure that was necessary to be considered a city could have actually emerged before the advent of a written language.

Previously it was believed that a system of written language was a necessary predecessor of that type of complex city. Most importantly, archaeologists believe this apparent city was thriving as far back as 4000 BC and independently from Sumer.

Until now, the oldest cities with developed seals and writing were thought to be Sumerian Uruk and Ubaid in Mesopotamia, which would be in the southern one-third of Iraq today.

The discovery at Hamoukar indicates that some of the fundamental ideas behind cities -including specialization of labor, a system of laws and government, and artistic development – may have begun earlier than was previously believed. The fact that this discovery is such a large city is what is most exciting to archaeologists.

While they have found small villages and individual pieces that date much farther back than Hamoukar, nothing can quite compare to the discovery of this size and magnitude. Discoveries have been made here that have never been seen before, including materials from Hellenistic and Islamic civilizations.

Excavation work undertaken in 2005 and 2006 has shown that this city was destroyed by warfare by around 3500 BC – probably the earliest urban warfare attested so far in the archaeological record of the Near East. Contiuned excavations in 2008 and 2010 expand on that.

Eye Idols made of alabaster or bone have been found in Tell Hamoukar. Eye Idols have also been found in Tell Brak, the biggest settlement from Syria’s Late Chalcolithic period.

Tell Brak, ancient Nagar, is a tell, or settlement mound, in the Upper Khabur area in Al-Hasakah Governorate, northeastern Syria. The site was occupied between the sixth and second millennia BC. A small settlement existed at the site as early as 6000 BCE, and materials from the Late Neolithic Halaf culture have been found there.

Occupation continued into the succeeding Ubaid and Uruk periods. Excavations and surface survey of the site and its surroundings reveal a city that developed from the early 4th millennium BCE (Late Chalcolithic 3 Period) contemporaneously with (or even slightly earlier than) better known cities of southern Mesopotamia, such as Uruk.

From ca 3500 BCE, Brak, along with many other settlements in northern Mesopotamia, was partly colonised by immigrants from Late Uruk southern Mesopotamia. Among extensive Late Uruk materials found at Brak is a standard text for educated scribes (the “Standard Professions” text, known from Uruk IV), part of the standardized education taught in the 3rd millennium BCE over a wide area of Syria and Mesopotamia.

The most famous of the Late Chalcolithic features is the 4th millennium BCE “Eye Temple”, which was excavated in 1937–38. The temple, built around 3500–3300 BCE, was named for the hundreds of small alabaster “eye idol” figurines, which were incorporated into the mortar with which the mudbrick temple was constructed.

The building’s surfaces were richly decorated with clay cones, copper panels and gold work, in a style comparable to contemporary temples of southern Mesopotamia, or Sumer.

The most dramatic discoveries during recent excavations (2007-8) are a series of mass graves dating to circa 3800–3600 BCE, which suggest that the process of urbanization was accompanied by internal social stress and an increase in the organization of warfare.

Third millennium BCE cuneiform texts from the city of Ebla and from Brak itself identify Nagar (Brak’s ancient name) as the major point of contact between the cities of the northern Levant, eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia. Nagar’s active commercial and cultural interchanges with Ebla are also recorded, as its power over the intervening city of Nabada (Tell Beydar).

The archaeological transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift from painted pottery domestically produced on a slow wheel to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on fast wheels.

By the time of the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC calibrated), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified, temple-centered cities (with populations of over 10,000 people) where centralized administrations employed specialized workers.

It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labor captured from the hill country, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts. Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area – from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as Central Iran.

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists (like that found at Tell Brak), had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.

Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and were most likely headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women. It is quite possible that the later Sumerian pantheon was modeled upon this political structure.

There was little evidence of institutionalized violence or professional soldiers during the Uruk period, and towns were generally unwalled. During this period Uruk became the most urbanised city in the world, surpassing for the first time 50,000 inhabitants.

The ancient Sumerian king list includes the early dynasties of several prominent cities from this period. The first set of names on the list is of kings said to have reigned before a major flood occurred. These early names may be fictional, and include some legendary and mythological figures, such as Alulim and Dumizid.

The end of the Uruk period coincided with the Piora oscillation, a dry period from c. 3200 – 2900 BC that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, called the Holocene climatic optimum.

In the late 3rd millennium BCE, Nagar lay at the northern edge of the Akkadian sphere of influence. The palace-stronghold of Naram-Sin of the 22nd century BCE, built at a time when Nagar was a northern administrative center of the Akkadian Empire, was more of a depot for the storage of collected tribute and agricultural produce than a residential seat. To the north, the nearby city of Urkesh may have retained some form of independence.

The excavators do not credit the Akkadians with political control of the city, and the political significance of cuneiform administrative documents in Akkadian retrieved from the palace are open to interpretation.

At the end of the Early Bronze Age, the site shrank in size, contemporary with a region-wide settlement disruption that some scholars have attributed to dramatic climate change.

The Shengavit Settlement is an archaeological site in present day Yerevan, Armenia located on a hill south-east of Lake Yerevan. It was inhabited during a series of settlement phases from approximately 3200 BC cal to 2500 BC cal in the Kura Araxes (Shengavitian) Period of the Early Bronze Age and irregularly re-used in the Middle Bronze Age until 2200 BC cal.

The town occupied an area of six hectares. It appears that Shengavit was a societal center for the areas surrounding the town due to its unusual size, evidence of surplus production of grains, and metallurgy, as well as its monumental 4 meter wide stone wall.

Four smaller village sites of Moukhannat, Tepe, Khorumbulagh, and Tairov have been identified and were located outside the walls of Shengavit. Its pottery makes it a type site of the Kura-Araxes or Early Transcaucasian Period and the Shengavitian culture area.

Archaeologists so far have uncovered large cyclopean walls with towers that surrounded the settlement. Within these walls were circular and square multi-dwelling buildings constructed of stone and mud-brick.

Inside some of the residential structures were ritual hearths and household pits, while large silos located nearby stored wheat and barley for the residents of the town. There was also an underground passage that led to the river from the town. Earlier excavations had uncovered burial mounds outside the settlement walls towards the south-east and south-west. More ancient graves still remain in the same vicinity.

A popular press source unfortunately has been cited misstating information from a 2010 press conference in Yerevan. In that conference Rothman described the Uruk Expansion trading network, and the likelihood that raw materials and technologies from the South Caucasus had reached the Mesopotamian homeland, which somehow was misinterpreted to say that Armenian culture was a source of Mesopototamian culture, which is not true. The Kura Araxes (Shengavitian) cultures and societies are a unique mountain phenomenon, evolved parallel to but not the same as Mesopotamian cultures.

The Bronze Age in the ancient Near East began in the 4th millennium BC. Cultures in the ancient Near East (often called, “the cradle of civilization”) practised intensive year-round agriculture, developed a writing system, invented the potter’s wheel, created a centralized government, law codes, and empires, and introduced social stratification, slavery, and organized warfare. Societies in the region laid the foundations for astronomy and mathematics.

The Hurrians had a reputation in metallurgy. The Sumerians borrowed their copper terminology from the Hurrian vocabulary. Copper was traded south to Mesopotamia from the highlands of Anatolia.

The Khabur Valley had a central position in the metal trade, and copper, silver and even tin were accessible from the Hurrian-dominated countries Kizzuwatna and Ishuwa situated in the Anatolian highland.

Gold was in short supply, and the Amarna letters inform us that it was acquired from Egypt. Not many examples of Hurrian metal work have survived, except from the later Urartu. Some small fine bronze lion figurines were discovered at Urkesh.

The Maykop culture (also spelled Maikop), ca. 3700-3000 BC, was a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia. It extends along the area from the Taman Peninsula at the Kerch Strait to near the modern border of Dagestan and southwards to the Kura River. The culture takes its name from a royal burial found in Maykop in the Kuban River valley.

In the south it borders the approximately contemporaneous Kura-Araxes culture (3500-2200 BC), which extends into eastern Anatolia and apparently influenced it. To the north is the Yamna culture, including the Novotitorovka culture (3300-2700), which it overlaps in territorial extent. It is contemporaneous with the late Uruk period in Mesopotamia.

The Kuban River is navigable for much of its length and provides an easy water-passage via the Sea of Azov to the territory of the Yamna culture, along the Don and Donets River systems. The Maykop culture was thus well-situated to exploit the trading possibilities with the central Ukraine area.

After the discovery of the Leyla-Tepe culture in the 1980s it was suggested that elements of the Maykop culture migrated to the south-eastern slopes of the Caucasus in modern Azerbaijan.

New data revealed the similarity of artifacts from the Maykop culture with those found recently in the course of excavations of the ancient city of Tell Khazneh in northern Syria, the construction of which dates back to 4000 BC.

The new high dating of the Maikop culture essentially signifies that there is no chronological hiatus separating the collapse of the Chalcolithic Balkan centre of metallurgical production and the appearance of Maikop and the sudden explosion of Caucasian metallurgical production and use of arsenical copper/bronzes.

More than forty calibrated radiocarbon dates on Maikop and related materials now support this high chronology; and the revised dating for the Maikop culture means that the earliest kurgans occur in the northwestern and southern Caucasus and precede by several centuries those of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) cultures of the western Eurasian steppes (cf. Chernykh and Orlovskaya 2004a and b).

The calibrated radiocarbon dates suggest that the Maikop ‘culture’ seems to have had a formative influence on steppe kurgan burial rituals and what now appears to be the later development of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) culture on the Eurasian steppes (Chernykh and Orlovskaya 2004a: 97).

In other words, sometime around the middle of the 4th millennium BCE or slightly subsequent to the initial appearance of the Maikop culture of the NW Caucasus, settlements containing proto-Kura-Araxes or early Kura-Araxes materials first appear across a broad area that stretches from the Caspian littoral of the northeastern Caucasus in the north to the Erzurum region of the Anatolian Plateau in the west.

For simplicity’s sake these roughly simultaneous developments across this broad area will be considered as representing the beginnings of the Early Bronze Age or the initial stages of development of the KuraAraxes/Early Transcaucasian culture.

The archaeological record seems to document a movement of peoples north to south across a very extensive part of the Ancient Near East from the end of the 4th to the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Although migrations are notoriously difficult to document on archaeological evidence, these materials constitute one of the best examples of prehistoric movements of peoples available for the Early Bronze Age.

The inhumation practices of the Maikop culture were characteristically Indo-European, typically in a pit, sometimes stone-lined, topped with a kurgan (or tumulus). Stone cairns replace kurgans in later interments. The Maykop kurgan was extremely rich in gold and silver artifacts; unusual for the time. The Maykop culture is believed to be one of the first to use the wheel.

The Maykop nobility enjoyed horse riding and probably used horses in warfare. It should be noted that the Maykop people lived sedentary lives, and horses formed a very low percentage of their livestock, which mostly consisted of pigs and cattle.

Archaeologists have discovered a unique form of bronze cheek-pieces, which consists of a bronze rod with a twisted loop in the middle and a thread through her nodes that connects with bridle, halter strap and headband. Notches and bumps on the edges of the cheek-pieces were, apparently, to fix nose and under-lip belts.

The culture has been described as, at the very least, a “kurganized” local culture with strong ethnic and linguistic links to the descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. It has been linked to the Lower Mikhaylovka group and Kemi Oba culture, and more distantly, to the Globular Amphora and Corded Ware cultures, if only in an economic sense.

Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, whose views are somewhat controversial, suggest that the Maykop culture (or its ancestor) may have been a way-station for Indo-Europeans migrating from the South Caucasus and/or eastern Anatolia to a secondary Urheimat on the steppe. This would essentially place the Anatolian stock in Anatolia from the beginning, and at least in this instance, agrees with Colin Renfrew’s Anatolian hypothesis.

Considering that some attempt has been made to unite Indo-European with the Northwest Caucasian languages, an earlier Caucasian pre-Urheimat is not out of the question. However, most linguists and archaeologists consider this hypothesis highly unlikely, and prefer the Eurasian steppes as the genuine IE Urheimat.

In the early 20th century, researchers established the existence of a local Maykop animal style in the found artifacts. This style was seen as the prototype for animal styles of later archaeological cultures: the Maykop animal style is more than a thousand years older than the Scythian, Sarmatian and Celtic animal styles. Attributed to the Maykop culture are petroglyphs which have yet to be deciphered.

The construction of artificial terrace complexes in the mountains is evidence of their sedentary living, high population density, and high levels of agricultural and technical skills. The terraces were built around the fourth millennium BC. They are among the most ancient in the world, but they are little studied. The longevity of the terraces (more than 5000 years) allows us to consider their builders unsurpassed engineers and craftsmen.

Filed under: Uncategorized