Ninurta

Teshup

Uranus

Ninurta

Ninurta (Nin Ur: God of War) in Sumerian and the Akkadian mythology of Assyria and Babylonia, was the god of Lagash, identified with Ningirsu with whom he may always have been identified. In older transliteration the name is rendered Ninib and Ninip, and in early commentary he was sometimes portrayed as a solar deity.

A number of scholars have suggested that either the god Ninurta or the Assyrian king bearing his name (Tukulti-Ninurta I) was the inspiration for the Biblical character Nimrod.

The cult of Ninurta can be traced back to the oldest period of Sumerian history. In the inscriptions found at Lagash he appears under his name Ningirsu, “the lord of Girsu”, Girsu being the name of a city where he was considered the patron deity.

In Nippur, Ninurta was worshiped as part of a triad of deities including his father, Enlil and his mother, Ninlil. In variant mythology, his mother is said to be the harvest goddess Ninhursag. The consort of Ninurta was Ugallu in Nippur and Bau when he was called Ningirsu.

In the late neo-Babylonian and early Persian period, syncretism seems to have fused Ninurta’s character with that of Nergal. The two gods were often invoked together, and spoken of as if they were one divinity.

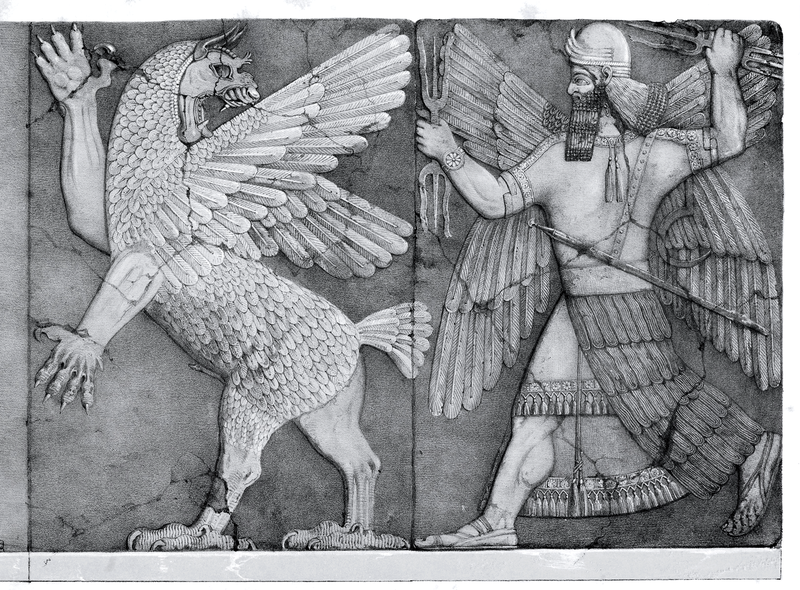

Ninurta often appears holding a bow and arrow, a sickle sword, or a mace named Sharur: Sharur is capable of speech in the Sumerian legend “Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta” and can take the form of a winged lion and may represent an archetype for the later Shedu.

Ninurta appears in a double capacity in the epithets bestowed on him, and in the hymns and incantations addressed to him. On the one hand he is a farmer and a healing god who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons; on the other he is the god of the South Wind as the son of Enlil, displacing his mother Ninlil who was earlier held to be the goddess of the South Wind.

In another legend, Ninurta battles a birdlike monster called Imdugud (Akkadian: Anzû); a Babylonian version relates how the monster Anzû steals the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil. The Tablets of Destiny were believed to contain the details of fate and the future.

Ninurta slays each of the monsters later known as the “Slain Heroes” (the Warrior Dragon, the Palm Tree King, Lord Saman-ana, the Bison-beast, the Mermaid, the Seven-headed Snake, the Six-headed Wild Ram), and despoils them of valuable items such as Gypsum, Strong Copper, and the Magilum boat). Eventually, Anzû is killed by Ninurta who delivers the Tablet of Destiny to his father, Enlil.

Enlil’s brother, Enki, was portrayed as Ninurta’s mentor from whom Ninurta was entrusted several powerful Mes, including the Deluge.

In the astral-theological system Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn, or perhaps as offspring or an aspect of Saturn. In his capacity as a farmer-god, there are similarities between Ninurta and the Greek Titan Kronos, whom the Romans in turn identified with their Titan Saturn.

Teshup and Uranus

Teshub was the Hurrian god of sky and storm. He was derived from the Hattian Taru. His Hittite and Luwian name was Tarhun (with variant stem forms Tarhunt, Tarhuwant, Tarhunta), although this name is from the Hittite root tarh- “to defeat, conquer”.

Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

According to Hittite myths, one of Teshub’s greatest acts was the slaying of the dragon Illuyanka. Myths also exist of his conflict with the sea creature (possibly a snake or serpent) Hedammu.

In the Hurrian schema, Teshub was paired with Hebat the mother goddess; in the Hittite, with the sun goddess Arinniti of Arinna – a cultus of great antiquity which has similarities with the venerated bulls and mothers at Çatalhöyük in the Neolithic era.

Teshub’s brothers are Aranzah (personification of the river Tigris), Ullikummi (stone giant) and Tashmishu. His son was called Sarruma, the mountain god.

The Hurrian creation myth of Teshub’s origin is similar to the Greek creation myth. In Hurrian religion, as in Sumeria mythology and later for Assyrians and Babylonians, Anu is the sky god and represented law and order.

His son Kumarbis bit off his genitals and spat out three deities, one of whom, Teshub, later deposed Kumarbis. As such it most likely shares a Proto-Indo-European cognate with the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony.

Uranus (Ouranos meaning “sky” or “heaven”) was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. His equivalent in Roman mythology was Caelus. In Ancient Greek literature, Uranus or Father Sky was the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth.

Most Greeks considered Uranus to be primordial, and gave him no parentage, believing him to have been born from Chaos, the primal form of the universe. However, in Hesiod’s Theogony, Hesiod claims Uranus to be the offspring of Gaia, the earth goddess, alone. Other sources cite Aether, known as Akmon or Acmon in Latin (possibly from the same route as “Acme”) one of the primordial deities, the first-born elementals, as his father.

Alcman and Callimachus elaborate that Uranus was fathered by Aether, the god of heavenly light and the upper air. Under the influence of the philosophers, Cicero, in De Natura Deorum (“Concerning the Nature of the Gods”), claims that he was the offspring of the ancient gods Aether and Hemera, Air and Day. According to the Orphic Hymns, Uranus was the son of Nyx, the personification of night.

Aether is the personification of the upper air. He embodies the pure upper air that the gods breathe, as opposed to the normal air (aer) breathed by mortals. Like Tartarus and Erebus, Aether may have had shrines in ancient Greece, but he had no temples and it is unlikely that he had a cult.

Uranus and Gaia were the parents of the first generation of Titans, and the ancestors of most of the Greek gods, but no cult addressed directly to Uranus survived into Classical times, and Uranus does not appear among the usual themes of Greek painted pottery. Elemental Earth, Sky and Styx might be joined, however, in a solemn invocation in Homeric epic.

In the Olympian creation myth, as Hesiod tells it in the Theogony, Uranus came every night to cover the earth and mate with Gaia, but he hated the children she bore him. Hesiod named their first six sons and six daughters the Titans, the three one-hundred-handed giants the Hekatonkheires, and the one-eyed giants the Cyclopes.

Uranus imprisoned Gaia’s youngest children in Tartarus, deep within Earth, where they caused pain to Gaia. She shaped a great flint-bladed sickle and asked her sons to castrate Uranus. Only Cronus, youngest and most ambitious of the Titans, was willing: he ambushed his father and castrated him, casting the severed testicles into the sea.

For this fearful deed, Uranus called his sons Titanes Theoi, or “Straining Gods.” From the blood that spilled from Uranus onto the Earth came forth the Giants, the Erinyes (the avenging Furies), the Meliae (the ash-tree nymphs), and, according to some, the Telchines. From the genitals in the sea came forth Aphrodite.

The learned Alexandrian poet Callimachus reported that the bloodied sickle had been buried in the earth at Zancle in Sicily, but the Romanized Greek traveller Pausanias was informed that the sickle had been thrown into the sea from the cape near Bolina, not far from Argyra on the coast of Achaea, whereas the historian Timaeus located the sickle at Corcyra; Corcyrans claimed to be descendants of the wholly legendary Phaeacia visited by Odysseus, and by circa 500 BCE one Greek mythographer, Acusilaus, was claiming that the Phaeacians had sprung from the very blood of Uranus’ castration.

After Uranus was deposed, Cronus re-imprisoned the Hekatonkheires and Cyclopes in Tartarus. Uranus and Gaia then prophesied that Cronus in turn was destined to be overthrown by his own son, and so the Titan attempted to avoid this fate by devouring his young. Zeus, through deception by his mother Rhea, avoided this fate.

These ancient myths of distant origins were not expressed in cults among the Hellenes. The function of Uranus was as the vanquished god of an elder time, before real time began.

After his castration, the Sky came no more to cover the Earth at night, but held to its place, and “the original begetting came to an end” (Kerényi). Uranus was scarcely regarded as anthropomorphic, aside from the genitalia in the castration myth. He was simply the sky, which was conceived by the ancients as an overarching dome or roof of bronze, held in place (or turned on an axis) by the Titan Atlas.

In formulaic expressions in the Homeric poems ouranos is sometimes an alternative to Olympus as the collective home of the gods; an obvious occurrence would be the moment in Iliad 1.495, when Thetis rises from the sea to plead with Zeus: “and early in the morning she rose up to greet Ouranos-and-Olympus and she found the son of Kronos …”

William Sale remarks that “… ‘Olympus’ is almost always used of [the home of the Olympian gods], but ouranos often refers to the natural sky above us without any suggestion that the gods, collectively live there”.

Sale concluded that the earlier seat of the gods was the actual Mount Olympus, from which the epic tradition by the time of Homer had transported them to the sky, ouranos. By the sixth century, when a “heavenly Aphrodite” (Urania) was to be distinguished from the “common Aphrodite of the people”, ouranos signifies purely the celestial sphere itself.

It is possible that Uranus was originally an Indo-European god, to be identified with the Vedic Váruṇa, the supreme keeper of order who later became the god of oceans and rivers, as suggested by Georges Dumézil, following hints in Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912).

Another possibility is that the Iranian supreme God Ahura Mazda is a development of the Indo-Iranian vouruna-mitra. Therefore this divinity has also the qualities of Mitra, which is the god of the falling rain.

The ancient Greeks and Romans knew of only five ‘wandering stars’: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Following the discovery of a sixth planet in the 18th century, the name Uranus was chosen as the logical addition to the series: for Mars (Ares in Greek) was the son of Jupiter, Jupiter (Zeus in Greek) the son of Saturn, and Saturn (Cronus in Greek) the son of Uranus. What is anomalous is that, while the others take Roman names, Uranus is a name derived from Greek in contrast to the Roman Caelus.

Filed under: Uncategorized