At present, Göbekli Tepe raises more questions for archaeology and prehistory than it answers. We do not know how a force large enough to construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was mobilized and paid or fed in the conditions of pre-Neolithic society.

This is the site of the worlds currently known oldest shrine or temple complex in the world, and the planet’s oldest known example of monumental architecture. It has also produced the oldest known life-size figure of a human.

Nevali Cori

Head of a large human sculpture – At the back of the head there is a snake-like curl.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic (10,000-8000 BC)

Nevali Cori

Relief with a turtle (symbol of fertility) between dancing human figures.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic (10,000-8000 BC)

-

-

-

The region of Upper-Mesopotamia provides a lot of sites that have the greatest importance for the understanding of the archaeology of this region. Especially the area of Southeast Anatolia within this region turns out to have an eminent position that has been revealed by the excavations and researches during the last decade.

The importance of Southeast Anatolia can not be minimized, especially when dealing with Neolithic sites. Among the remarkable sites of Çayönü and Göbekli Tepe (Turkish: “Potbelly Hill”) or Portasar (Armenian: Պորտասար), there is a third Neolithic site that also deserves the attention: Nevalı Çori in the province of Şanlıurfa.

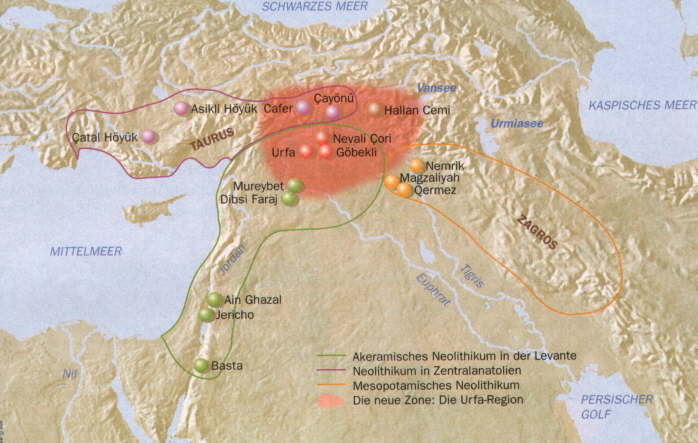

The term “Fertile Crescent” was used by James Henry Breasted to designate the geographical zone in which the transition from the Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic economy (hunting, food-collection) to the Neolithic way of production first took place, that is producing food by practising agriculture and animal husbandry.

This geographical area includes the foothills of the mountain ranges of the Near East, stretching from Asia Minor (Taurus mountains) and Palestine to western Iran (Zagros mountains). The ideal geomorphological and climatic conditions established here during the early Holocene offered an ideal environment for permanent settlement.

Formerly, it was believed that the Neolithic way of life was first established in the area of south Lebanon and general in Palestine, as the settlement of Jericho was the first example to reveal the above mentioned features. Moreover, in Palestine and in north Syria, the first indications of systematic plant cultivation appeared around 9000 BC implying a major change in economy.

Recent research carried out in Upper Mesopotamia, the area stretching from the rivers Tigris and Eurates (southeastern Turkey), to the north of historic Mesopotamia (Assyria, Babylonia), has revealed the pioneering ideas of the inhabitants of this area in developing new ways of exploiting the natural environment and establishing new economic conditions.

These pioneering ideas emerged approximately at the end of the 9th millenium in agriculture and farming, and ensured the production of grain and meat on a permanent basis. Such developments facilitated the permanent settlement of small communities (Cayonu, Gorucutepe) and put an end to the long nomadic existence of human populations.

Approximately 11,500 years ago, towards the end of the last Ice Age as the weather became warmer, some of our early ancestors in the northern region of what we now know as the Fertile Crescent began to move their places of religious ritual beyond the cave and rock walls.

Göbekli Tepe, an archaeological site at the top of a mountain ridge in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, northeast of the town of Şanlıurfa, is the first evidence to date of this transition. This extraordinary man-made place of worship heralds a new period of creative expression we know as the Neolithic (“new stone”) era.

The imposing stratigraphy of Göbekli Tepe attests to many centuries of activity, beginning at least as early as the epipaleolithic, or Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), in the 10th millennium BC. The PPNA buildings have been dated to about the close of the 10th millennium BCE. There are remains of smaller houses from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) era and a few epipalaeolithic finds as well.

The tell includes two phases of ritual use dating back to the 10th-8th millennium BC. During the first phase (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected. More than 200 pillars in about 20 circles are currently known through geophysical surveys. Each pillar has a height of up to 6 m (20 ft) and a weight of up to 20 tons. They are fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the bedrock.

In the second phase (Pre-pottery Neolithic B (PPNB)), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. The site was abandoned after the PPNB-period. Younger structures date to classical times.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage in early Levantine Neolithic culture, dating around 8000 to 7000 BC. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was not in use yet. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).

Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Earlier Natufian but shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of north eastern Anatolia.

The culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BC, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries.

In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of Ghassulian culture.

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period which existed between 8,200 and 7,900 BP. Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6200 BC, partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon animal domesticates, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in Southern Palestine, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.

The Semitic family is a member of the larger Afroasiatic family, all of whose other five or more branches have their origin in North Africa and North East Africa. Largely for this reason, the ancestors of Proto-Semitic speakers were originally believed by some to have first arrived in the Middle East from North Africa, possibly as part of the operation of the Saharan pump, around the late Neolithic.

Diakonoff sees Semitic originating between the Nile Delta and Canaan as the northernmost branch of Afroasiatic. A recent Bayesian analysis of alternative Semitic histories supports the latter possibility and identifies an origin of Semitic languages in the Levant around 3,750 BC with a single introduction from southern Arabia into Africa around 800 BC.

In one interpretation, Proto-Semitic itself is assumed to have reached the Arabian Peninsula by approximately the 4th millennium BC, from which Semitic daughter languages continued to spread outwards.

When written records began in the late 4th millennium BC, the Semitic-speaking Akkadians (Assyrians/Babylonians) were entering Mesopotamia from the deserts to the west, and were probably already present in places such as Ebla in Syria. Akkadian personal names began appearing in written record in Mesopotamia from the late 29th Century BC.

By the late 3rd millennium BC, East Semitic languages, such as Akkadian and Eblaite, were dominant in Mesopotamia and north east Syria, while West Semitic languages, such as Amorite, Canaanite and Ugaritic, were probably spoken from Syria to the Arabian Peninsula, although Old South Arabian is considered by most people to be South Semitic despite the sparsity of data.

The Akkadian language of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia had become the dominant literary language of the Fertile Crescent, using the cuneiform script that was adapted from the Sumerians.

Some historians, such as Jean Bottéro, have made the claim that Mesopotamian religion is the world’s oldest religion, although there are several other claims to that title, including Göbekli Tepe, or Portasar. However, as writing was invented in Mesopotamia it is certainly the oldest in written history.

It is generally believed that an elite class of religious leaders supervised the work and later controlled whatever ceremonies took place. If so, this would be the oldest known evidence for a priestly caste – much earlier than such social distinctions developed elsewhere in the Near East.

It is connected with the initial stages of an incipient Neolithic, and it is suggested that the Neolithic revolution, i.e., the beginnings of grain cultivation, took place here. It is one of several sites in the vicinity of Karaca Dağ, an area which geneticists suspect may have been the original source of at least some of our cultivated grains.

Recent DNA analysis of modern domesticated wheat compared with wild wheat has shown that its DNA is closest in sequence to wild wheat found on Mount Karaca Dağ 20 miles (32 km) away from the site, suggesting that this is where modern wheat was first domesticated.

Based on comparisons with other shrines and settlements it is assumed that the belief systems of the groups that created Göbekli Tepe was shamanic practices and that the T-shaped pillars represent human forms, perhaps ancestors, whereas a fully articulated belief in gods only developing later in Mesopotamia, associated with extensive temples and palaces.

This corresponds well with an ancient Sumerian belief that agriculture, animal husbandry, and weaving were brought to mankind from the sacred mountain Ekur, which was inhabited by Annuna deities, very ancient gods without individual names. This story is a primeval oriental myth that preserves a partial memory of the emerging Neolithic.

Scholars such as the French archaeologist Jacques Cauvin suggest that the massive pillar structures mark a “revolution of Symbols” – a “psycho-cultural” change enabling the imagination of a structured cosmos and supernatural world in symbolic form. Perhaps, for the first time, human beings imagine gods, supernatural beings resembling humans that exist in the other worlds.

As foragers, their population may well have increased to a size that eventually made a more hierarchical organization imperative. Shamans would still be looked to for guidance and from this already somewhat elevated position they were perhaps able to take control. As community leaders, a priesthood of sorts, they would command the numbers of people needed to initiate this transformation: to create a new tiered cosmos beyond the cave walls.

It is also apparent that the animal and other images give no indication of organized violence, i.e. there are no depictions of hunting raids or wounded animals, and the pillar carvings ignore game on which the society mainly subsisted, like deer, in favor of formidable creatures like lions, snakes, spiders, and scorpions.

Göbekli Tepe is regarded as an archaeological discovery of the greatest importance since it could profoundly change the understanding of a crucial stage in the development of human society. Ian Hodder of Stanford University said, “Göbekli Tepe changes everything”.

It shows that the erection of monumental complexes was within the capacities of hunter-gatherers and not only of sedentary farming communities as had been previously assumed. As excavator Klaus Schmidt puts it, “First came the temple, then the city.”

Not only its large dimensions, but the side-by-side existence of multiple pillar shrines makes the location unique. There are no comparable monumental complexes from its time. Nevalı Çori, a Neolithic settlement also excavated by the German Archaeological Institute and submerged by the Atatürk Dam since 1992, is 500 years later.

Its T-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its shrine was located inside a village. The roughly contemporary architecture at Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture, and Çatalhöyük, perhaps the most famous Anatolian Neolithic village, is 2,000 years younger.

At present, though, Göbekli Tepe raises more questions for archaeology and prehistory than it answers. It remains unknown how a force large enough to construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was mobilized and compensated or fed in the conditions of pre-sedentary society.

Scholars cannot “read” the pictograms, and do not know for certain what meaning the animal reliefs had for visitors to the site. The variety of fauna depicted, from lions and boars to birds and insects, makes any single explanation problematic.

As there is little or no evidence of habitation, and the animals pictured are mainly predators, the stones may have been intended to stave off evils through some form of magic representation. Alternatively, they could have served as totems.

The assumption that the site was strictly cultic in purpose and not inhabited has also been challenged by the suggestion that the structures served as large communal houses, “similar in some ways to the large plank houses of the Northwest Coast of North America with their impressive house posts and totem poles.”

It is not known why every few decades the existing pillars were buried to be replaced by new stones as part of a smaller, concentric ring inside the older one. Human burial may or may not have occurred at the site.

The reason the complex was carefully backfilled remains unexplained. Until more evidence is gathered, it is difficult to deduce anything certain about the originating culture or the site’s significance.

Şanlıurfa, often simply known as Urfa in daily language (Arabic Ar-Ruhā, Armenian Uṙha, Kurdish Riha, Syriac Urhoy), and in ancient times Edessa in Greek, is a city in south-eastern Turkey, and the capital of Şanlıurfa Province. The earliest name of the city was Adma, also written Adme, Admi, Admum, which first appeared in Assyrian cuneiforms in the 7th century BC.

The history of Şanlıurfa is recorded from the 4th century BC, but may date back at least to 9000 BC, when there is ample evidence for the surrounding sites at Duru, Harran and Nevali Cori. Within the further area of the city are three neolithic sites known: Göbekli Tepe, Gürcütepe and the city itself, where the life-sized limestone “Urfa statue” was found during an excavation in Balıklıgöl.

The city was one of several in the upper Euphrates-Tigris basin, the fertile crescent where agriculture began. According to Turkish Muslim traditions Urfa (its name since Byzantine days) is the biblical city of Ur of the Chaldees, due to its proximity to the biblical village of Harran.

The old city of Şanliurfa was constructed near the Karakoyun River (Dayshan-Skirtos) before the Justinian period (527-565a.d.), and at that time there were some lakes that were considered to be holy. To the south of the city were high rocky hills, and the broad Harran Plain lies to the east; there is a large open area that climbs in elevation to the north of the city. The strategic advantages made this an ideal location for early Neolithic settlement.

In 1997 evidence for a stratified Early Neolithic settlement was found on Yeni Yol Caddesi, a narrow street in the central part of Sanhurfa towards the southwestern part of town near the surrounding city wall that climbs northward from the southern edge of the city in a section of town called Yeni Mahalle.

In 1993, during construction of a building complex to the east of this area, a limestone statue of a male nearly 1.90 m high was recovered. A comparison of this statue with the large sculptures excavated at Nevali Cori indicate that it also belongs to the Early Neolithic. Both of these finds constitute the first verification of Early Neolithic occupation under the city of Şanliurfa.

During reconstruction of the street in1993, when it was lowered and widened, a stratigraphic section nearly 2m high and 70 m long appeared. Most of the thickness of the profile is datable to the Early Neolithic, with Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic material appearing in the upper reaches. There is no sign of Bronze Age occupation in this profile.

In 1997 an in situ section of this profile 15 m long and 0.5 m wide was investigated. There were no Neolithic potsherds, but many lithics artifacts were recovered, including 239 flint tools and15 tools made of obsidian. The tools included projectile points, perforators, burins, endscrapers, and side scrapers. Somebone tools also occurred here, as well as basalt stones that perhaps used as weights to anchor tents or tent poles. The profile also contained four terrazzo floor areas similar to those at Cayonii, Gobekli Tepe, and Nevah Cori (cf. Hauptmann 1993; Ozdogan 1995).

An Early Neolithic age can be assigned to these layers based on typological analysis of the tools. One projectile point is a variant of the Helwan point and may be dated to the PPNA. Others show close similarities to El Khiam and Nevali Cori points dated to the PPNA and Early PPNB periods (Schmidt 1996). No Palmyra points (Schmidt and Beile-Bohn 1996) or Cayonii Tools, ascribable to later PPNB periods, were found. Compared to the Nevali Cori stratigraphy (which is some distance away), the Sanli urfa material seems to fall between Strata I and III1.

The profile is currently under the city wall and modern buildings, but a basalt grinding stone could be seen and examined. The presence of terrazzo floors and the larger-than-life human statue indicate at least one special building.

Gobekli Tepe site located atop a mountain not far from Sanliurfa (Beile-Bohnetal.1998). Although the reareritual aspects to Gobekli Tepe (Schmidt 1998), there are no holy springs or ponds as there were at Sanliurfa. This might indicate that Sanliurfa played a greater role in terms of ritual activity. With additional excavations at the Sanliurfa site, a better idea of its layout can be obtained and a more reliable comparison with Gobekli Tepe can be achieved.

Nevalı Çori was an early Neolithic settlement on the middle Euphrates, in Şanlıurfa Province, Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey. The site is famous for having revealed some of the world’s second ancient known temples and monumental sculpture. Together with the site of Göbekli Tepe (older), it has revolutionised scientific understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic.

The site was examined from 1983 to 1991 in the context of rescue excavations during the erection of the Atatürk Dam below Samsat. Excavations were conducted by a team from the University of Heidelberg under the direction of Professor Harald Hauptmann. Together with numerous other archaeological sites in the vicinity, Nevalı Çori has since been inundated by the dammed waters of the Euphrates.

Nevalı Çori could be placed within the local relative chronology on the basis of its flint tools. The occurrence of narrow unretouched Byblos-type points places it on Oliver Aurenche’s Phase 3, i.e. early to middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB). Some tools indicate continuity into Phase 4, which is similar in date to Late PPNB.

An even finer chronological distinction within Phase 3 is permitted by the settlement’s architecture; the house type with underfloor channels, typical of Nevalı Çori strata I-IV, also characterises the “Intermediate Layer” at Çayönü, while the differing plan of the single building in stratum V, House 1, is more clearly connected to the buildings of the “Cellular Plan Layer” at Çayönü.

In terms of absolute dates, 4 radiocarbon dates have been determined for Nevalı Çori. Three are from Stratum II and date it with some certainty to the second half of the 9th millennium BC, which coincides with early dates from Çayönü and with Mureybet IVA and thus supports the relative chronology above. The fourth dates to the 10th millennium BC, which, if correct, would indicate the presence of an extremely early phase of PPNB at Nevalı Çori.

The settlement had five architectural levels. The excavated architectural remains were of long rectangular houses containing two to three parallel flights of rooms, interpreted as mezzanines. These are adjacent to a similarly rectangular ante-structure, subdivided by wall projections, which should be seen as a residential space.

This type of house is characterized by thick, multi-layered foundations made of large angular cobbles and boulders, the gaps filled with smaller stones so as to provide a relatively even surface to support the superstructure.

These foundations are interrupted every 1-1.5m by underfloor channels, at right angles to the main axis of the houses, which were covered in stone slabs but open to the sides. They may have served the drainage, aeration or the cooling of the houses. 23 such structures were excavated, they are strikingly similar to structures from the so-called channeled subphase at Çayönü.

An area in the northwest part of the village appears to be of special importance. Here, a cult complex had been cut into the hillslope. It had three subsequent architectural phases, the most recent belonging to Stratum III, the middle one to Stratum II and the oldest to Stratum I. The two more recent phases also possessed a terrazzo-style lime cement floor, which did not survive from the oldest phase.

Parallels are known from Cayönü and Göbekli Tepe. Monolithic pillars similar to those at Göbekli Tepe were built into its dry stone walls, its interior contained two free-standing pillars of 3 m height. The excavator assumes light flat roofs. Similar structures are only known from Göbekli Tepe so far.

The local limestone was carved into numerous statues and smaller sculptures, including a more than life-sized bare human head with a snake or sikha-like tuft. There is also a statue of a bird. Some of the pillars also bore reliefs, including ones of human hands. The free-standing anthropomorphic figures of limestone excavated at Nevalı Çori belong to the earliest known life-size sculptures. Comparable material has been found at Göbekli Tepe.

Several hundred small clay figurines (about 5 cm high), most of them depicting humans, have been interpreted as votive offerings. They were fired at temperatures between 500-600°C, which suggests the development of ceramic firing technology before the advent of pottery proper.

Some of the houses contained depositions of human skulls and incomplete skeletons. Plastered human skulls are reconstructed human skulls that were made in the ancient Levant between 7000 and 6000 BC in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. They represent some of the oldest forms of art in the Middle East and demonstrate that the prehistoric population took great care in burying their ancestors below their homes. The skulls denote some of the the earliest sculptural examples of portraiture in the history of art.

One skull was accidentally unearthed in the 1930s by the archaeologist John Garstang at Jericho in the West Bank. A number of plastered skulls from Jericho were discovered by the British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950s.

Other sites where plastered skulls were excavated include Ain Ghazal and Amman, Jordan, and Tell Ramad, Syria. Most of the plastered skulls were from adult males, but some belonged to women and children.

The plastered skulls represent some of the earliest forms of burial practices in the southern Levant. During the Neolithic period, the deceased were often buried under the floors of their homes.

Sometimes the skull was removed, and its cavities filled with plaster and painted. In order to create more life-like faces, shells were inset for eyes, and paint was used to represent facial features, hair, and moustaches.

Some scholars believe that this burial practice represents an early form of ancestor worship, where the plastered skulls were used to commemorate and respect family ancestors. Other experts argue that the plastered skulls could be linked to the practice of head hunting, and used as trophies. Plastered skulls provide evidence about the earliest arts and religious practices in the ancient Near East.

Karahan Tepe settlement was first discovered in 1997, but was surveyed in 2000 and again in 2011 within the course of the Sanlıurfa City Cultural Inventory. The settlements are located within the boundaries of Sanlıurfa (ancient name Edessa), a city in southeast Turkey.

The settlement lies on a plateau known as the Tektek Mountains (Tektek Dagları) 63km east of Sanlıurfa. Like Göbekli Tepe, Hamzan Tepe and Sanlıurfa Yeni Mahalle PPN (Pre-Pottery Neolithic period) settlements located around the Harran Plain in the Urfa Region, Karahan Tepe is also a PPN settlement located on a high plateau foot on the eastern side of Harran Plain.

During the surveys on Karahan Tepe in 2000, basin-like pools carved in bedrock and a considerable number of tools of flint, obsidian, river pebble, and limestone were discovered. The finds show that the settlement was in use in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period.

Furthermore, there were many T-shaped pillars, which are also familiar from Nevali Çori, Sefer Tepe, Hamzan Tepe and Göbekli Tepe. As a result of a new survey in 2011, a new snake-shaped relief was found carved on a T-shaped pillar, of which half was formerly revealed by illegal excavations.

In the light of all these finds it seems that Karahan Tepe, the upper levels of Gopekli Tepe and Nevali Cori III (Schmidt 1998b, 1998c) are contemporaneous. Since there are not any Palmyra Points (Schmidt 1996) or Cayona Tools at the Karahail settlement, it is possible for us to date this settlement as MPPNB.

The distance between Basharan Höyük, Herzo Tepe, Kocanizam Tepe and Sefer Tepe settlements varies in the range of 2 to 8 km. Furthermore, all four settlements align in succession in north-south direction.

Sefer Tepe settlement accommodating “T” shaped pillars is in the middle of other settlements with distance to the settlements varying in the range of 3 to 5 km. This situation points out to a settlement style not encountered before at Pre-Pottery Neolithic period settlements.

The settlements from early stages of Pre-Pottery Neolithic period are generally founded on or at the slope of high plateaus in the region. Likewise, Basharan Höyük, Herzo Tepe and Kocanizam Tepe settlements are settlements founded on high plateaus and on the bedrock.

This style of settlement tradition is already known in the region from Sefer Tepe, Tashlı Tepe, Karahan Tepe, Göbekli Tepe, Shanlıurfa-Yeni Mahalle and Hamzan Tepe Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlements.

Round-planned civil architecture buildings are not yet discovered at any of the settlements in the region characterized with “T” shaped pillars. Presence of round-planned structures constructed for civil purposes encountered at Herzo Tepe and Hamzan Tepe is important as it illustrates that two different architectural traditions were used in the region during Pre-Pottery Neolithic period.

Existence of settlements featuring the properties of cult centers, such as Göbekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, Tashlı Tepe and Sefer Tepe, discovered during the studies conducted to the present day suggests that civil settlements must also be present in the region.

Basharan Höyük, Kocanizam Tepe and Herzo Tepe might be Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlements which are founded very close to each other and featuring the properties of civil architecture. Sefer Tepe settlement, which features the properties of the cult center, on the other hand is founded at the center of these settlements.

By virtue of the systematic research studies, it would be possible to encounter and discover many settlements in the region representing the civil architecture tradition as well as the settlements featuring the properties of a cult center

Karahan Tepe – a new cultural centre in the Urfa area in Turkey

New Early-Neolithic Settlement: Karahan Tepe

The plastered skulls of Jericho

Ancient Man and His First Civilizations

Settlement Pattern in Southeast Anatolia

The Human Journey: The Neothlithic Era

New Pre-Pottery Neolithic Settlements From Viranşehir District

Filed under: Uncategorized