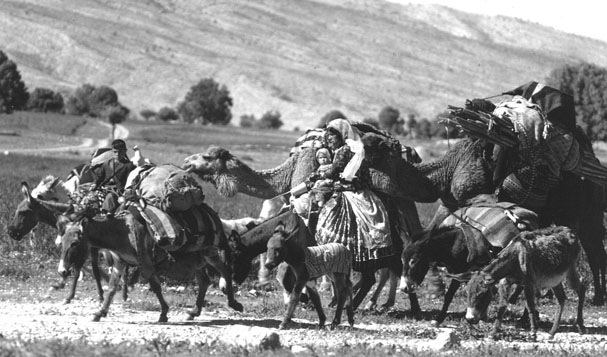

Nomadic pastoralism is a form of pastoralism where livestock are herded in order to find fresh pastures on which to graze following an irregular pattern of movement. This is in contrast with transhumance where seasonal pastures are fixed.

The herded livestock include cattle, yaks, sheep, goats, reindeer, horses, donkeys or camels, or mixtures of species. Nomadic pastoralism is commonly practised in regions with little arable land, typically in the developing world.

Historically nomadic herder lifestyles have led to warrior-based cultures that have made them fearsome enemies of settled people. Tribal confederations built by charismatic nomadic leaders have sometimes held sway over huge areas as incipient state structures whose stability is dependent upon the distribution of taxes, tribute and plunder taken from settled populations.

The nomadic pastoralism was a result of the Neolithic revolution. During the revolution, humans began domesticating animals and plants for food and started forming cities. Nomadism generally has existed in symbiosis with such settled cultures trading animal products (meat, hides, wool, cheeses and other animal products) for manufactured items not produced by the nomadic herders.

Andrew Sherratt demonstrates that “early farming populations used livestock mainly for meat, and that the other applications were explored as agriculturalists adapted to new conditions, especially in the semi‐arid zone.”

Nomadic pastoralists have long played a prominent role in the economy of the Middle East, but their numbers seem to vary according to climatic conditions and the force of neighbouring states inducing permanent settlement.

In the past it was asserted that pastoral nomads left no presence archaeologically but this has now been challenged. Pastoral nomadic sites are identified based on their location outside the zone of agriculture, the absence of grains or grain-processing equipment, limited and characteristic architecture, a predominance of sheep and goat bones, and by ethnographic analogy to modern pastoral nomadic peoples.

Henri Fleisch tentatively suggested the Shepherd Neolithic industry of Lebanon may date to the Epipaleolithic and that it may have been used by one of the first cultures of nomadic shepherds in the Beqaa valley.

The period of the Late Bronze Age seems to have coincided with increasing aridity, which weakened neighbouring states and induced transhumance pastoralists to spend longer and longer periods with their flocks. Urban settlements diminished in size, until eventually fully nomadic pastoralist lifestyles came to dominate the region.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) is a division of the Neolithic developed by Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the southern Levant region. It denotes the first stage in early Levantine Neolithic culture, dating around 8000 to 7000 BC.

Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.

PPNA were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was not in use yet. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).

The following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) was like the earlier PPNA people developed from the Earlier Natufian, but shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of north eastern Anatolia, also known as the armenian Highland.

Sites from this period found in the Levant utilizing rectangular floor plans and plastered floor techniques were found at Ain Ghazal, Yiftahel (western Galilee), and Abu Hureyra (Upper Euphrates).

The PPNB culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BC, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries.

In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of Ghassulian culture.

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period. Juris Zarins has proposed that pastoral nomadism, or a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, began as a cultural lifestyle in the wake of the climatic crisis of 6200 BC, and spreading Proto-Semitic languages.

This partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon domesticated animals, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing pastoral nomadism spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.

The Ghassulian culture, that has been identified at numerous other places in what is today southern Israel, especially in the region of Beersheba, correlates closely with the Amratian of Egypt and may have had trading affinities (e.g., the distinctive churns, or “bird vases”) with early Minoan culture in Crete.

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant (c. 3800–c. 3350 BC). The dates for Ghassulian are dependent upon 14C (radiocarbon) determinations, which suggest that the typical later Ghassulian began sometime around the mid-5th millennium and ended ca. 3800 BC. The transition from Late Ghassulian to EB I seems to have been ca. 3800-3500 BC.

Considered to correspond to the Halafian culture, Tell Hassuna and Tell Ubaid of North Syria and Mesopotamia, its type-site, Tulaylat al-Ghassul, is located in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea in modern Jordan and was excavated in the 1930s.

The Ghassulian stage was characterized by small hamlet settlements of mixed farming peoples, and migrated southwards from Syria into Israel. Houses were trapezoid-shaped and built mud-brick, covered with remarkable polychrome wall paintings.

Their pottery was highly elaborate, including footed bowls and horn-shaped drinking goblets, indicating the cultivation of wine. Several samples display the use of sculptural decoration or of a reserve slip (a clay and water coating partially wiped away while still wet). The Ghassulians were a Chalcolithic culture as they also smelted copper.

Funerary customs show evidence that they buried their dead in stone dolmens, a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of three or more upright stones supporting a large flat horizontal capstone (table), although there are also more complex variants. Most date from the early Neolithic period (4000 to 3000 BC).

The Semitic family is a member of the larger Afroasiatic family, all of whose other five or more branches have their origin in North Africa and North East Africa. Largely for this reason, the ancestors of Proto-Semitic speakers were originally believed by some to have first arrived in the Middle East from North Africa, possibly as part of the operation of the Saharan pump, around the late Neolithic.

Diakonoff sees Semitic originating between the Nile Delta and Canaan as the northernmost branch of Afroasiatic. A recent Bayesian analysis of alternative Semitic histories supports the latter possibility and identifies an origin of Semitic languages in the Levant around 3,750 BC with a single introduction from southern Arabia into Africa around 800 BC.

In one interpretation, Proto-Semitic itself is assumed to have reached the Arabian Peninsula by approximately the 4th millennium BC, from which Semitic daughter languages continued to spread outwards.

When written records began in the late 4th millennium BC, the Semitic-speaking Akkadians (Assyrians/Babylonians) were entering Mesopotamia from the deserts to the west, and were probably already present in places such as Ebla in Syria. Akkadian personal names began appearing in written record in Mesopotamia from the late 29th Century BC.

By the late 3rd millennium BC, East Semitic languages, such as Akkadian and Eblaite, were dominant in Mesopotamia and north east Syria, while West Semitic languages, such as Amorite, Canaanite and Ugaritic, were probably spoken from Syria to the Arabian Peninsula, although Old South Arabian is considered by most people to be South Semitic despite the sparsity of data.

The Akkadian language of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia had become the dominant literary language of the Fertile Crescent, using the cuneiform script that was adapted from the Sumerians.

The Society and Its Environment

Filed under: Uncategorized