The Samarra bowl, at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin.

The swastika in the center of the design is a reconstruction.

Intro

The Levantine corridor is the relatively narrow strip between the Mediterranean Sea to the northwest and deserts to the southeast which connects Africa to Eurasia. This corridor is a land route of migrations of animals between Eurasia and Africa.

In particular, it is believed that early hominids spread from Africa to Asia and Europe via the Levantine corridor and Horn of Africa. The corridor is named after the Levant.

The Levantine Corridor is the western part of the Fertile Crescent, the eastern part being Mesopotamia. Botanists recognize this area as a dispersal route of plant species.

Through genetic studies, researchers have found that the Levantine corridor was more important through Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods for bi-directional migrations of peoples (and certain chromosomes) between Africa and Eurasia than was the Horn of Africa.

The first sedentary villages were established around fresh water springs and lakes in the Levantine corridor by the Natufian culture. The term is used frequently by archaeologists as an area that includes Cyprus, where important developments occurred during the Neolithic revolution.

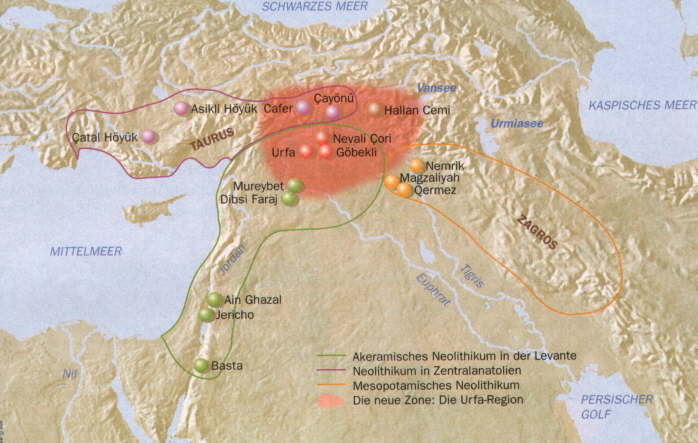

The Fertile Crescent is a term for an old fertile area north, east and west of the Arabian Desert in Southwest Asia. The Mesopotamian valley and the Nile valley fall under this term even though the mountain zone around Mesopotamia is the natural zone for the transition in a historical sense.

As a result of a number of unique geographical factors the Fertile Crescent have an impressive history of early human agricultural activity and culture. Besides the numerous archaeological sites with remains of skeletons and cultural relics the area is known primarily for its excavation sites linked to agricultural origins and development of the Neolithic era.

It was here, in the forested mountain slopes of the periphery of this area that agriculture originated in an ecologically restricted environment. The western zone and areas around the upper Euphrates gave growth to the first known Neolithic farming communities with small, round houses, also referred to as Pre Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) cultures, which dates to just after 10,000 BC and include areas such as Jericho, the world’s oldest city.

Early agriculture is believed to have originated and become widespread in Southwest Asia around 10,000–9,000 BP, though earlier individual sites have been identified. The Fertile Crescent region of Southwest Asia is the centre of domestication for three cereals (einkorn wheat, emmer wheat and barley) four legumes (lentil, pea, bitter vetch and chickpea) and flax.

The Mediterranean climate consists of a long dry season with a short period of rain, which may have favored small plants with large seeds, like wheat and barley. The Fertile Crescent also had a large area of varied geographical settings and altitudes and this variety may have made agriculture more profitable for former hunter-gatherers in this region in comparison with other areas with a similar climate.

Finds of large quantities of seeds and a grinding stone at the paleolithic site of Ohalo II in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee, dated to around 19,400 BP has shown some of the earliest evidence for advanced planning of plant food consumption and has led Ehud Weiss, an archeologist, to suggest that humans at Ohalo II processed the grain before consumption.

Tell Aswad is oldest site of agriculture with domesticated emmer wheat dated by Willem van Zeist and his assistant Johanna Bakker-Heeres to 8800 BC. Soon after came hulled, two-row barley found domesticated earliest at Jericho in the Jordan valley and Iraq ed-Dubb in Jordan.

Other sites in the Levantine corridor that show the first evidence of agriculture include Wadi Faynan 16 and Netiv Hagdud. Jacques Cauvin noted that the settlers of Aswad did not domesticate on site, but “arrived, perhaps from the neighbouring Anti-Lebanon, already equipped with the seed for planting”.

The first PPNB period involved construction of massive earth architecture, layering soil with reeds to construct walls. The inhabitants of Tell Aswad invented the brick on site by modelling earth clods with beds of reeds, which they then formed into raw bricks and eventually dried in later stages. Houses were round from beginning to the end of the settlement, elliptical or polygonal and were partly buried or laid.

The orientation of the openings is most often to the East. This conforms with sites in the Southern Levant, whereas Northern Euphrates Valley sites generally display rectangular houses.

The Heavy Neolithic Qaraoun culture has been identified at around fifty sites in Lebanon around the source springs of the River Jordan, however the dating of the culture has never been reliably determined.

The Tahunian is variously referred to as an archaeological culture, flint industry and period of the Palestinian Stone Age around Wadi Tahuna near Bethlehem. It was discovered and termed by Denis Buzy during excavations in 1928.

Due to the early date and problems with the stratigraphy of the excavations at Wadi Tahuna, a great deal of debate has been put forward regarding the definition and position of the Tahunian within the sequences of Mesolithic, Epipaleolithic, Natufian, Khiamian, Heavy Neolithic, Pre-Pottery Neolithic A, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and Neolithic and its relation to other Neolithic cultures such as the Qaraoun culture.

In the search for naming conventions for the culture that started the Neolithic Revolution, this has reduced Avi Gopher to calling it a “Tahunian Pandora’s box”, resulting in offshoots in terminology such as Proto-Tahunian. It is no longer widely used but would appear to be an early PPNB culture of the Levantine corridor of around 8800 BC according to the ASPRO chronology.

During the subsequent PPNB from 9000 BC these communities developed into larger villages with farming and animal husbandry as the main source of livelihood, with settlement in the two-story, rectangular house. Man now entered in symbiosis with grain and livestock species, with no opportunity to return to hunter – gatherer societies.

Heavy Neolithic and Shepherd Neolithic

Heavy Neolithic (alternatively, Gigantolithic) is a style of large stone and flint tools (or industry) associated primarily with the Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon, dating to the Epipaleolithic or early Pre-pottery Neolithic at the end of the Stone Age. The type site for the Qaraoun culture is Qaraoun II.

The term “Heavy Neolithic” was translated by Lorraine Copeland and Peter J. Wescombe from Henri Fleisch’s term “gros Neolithique”, suggested by Dorothy Garrod (in a letter dated February 1965) for adoption to describe the particular flint industry that was identified at sites near Qaraoun in the Beqaa Valley. The industry was also termed “Gigantolithic” and confirmed as Neolithic by Alfred Rust and Dorothy Garrod.

Gigantolithic was initially mistaken for Acheulean or Levalloisian by some scholars. Diana Kirkbride and Henri de Contenson suggested that it existed over a wide area of the fertile crescent. Heavy Neolithic industry occurred before the invention of pottery and is characterized by huge, coarse, heavy tools such as axes, picks and adzes including bifaces.

There is no evidence of polishing at the Qaraoun sites or indeed of any arrowheads, burins or millstones. Henri Fleisch noted that the culture that produced this industry may well have led a forest way of life before the dawn of agriculture. Jacques Cauvin proposed that some of the sites discovered may have been factories or workshops as many artifacts recovered were rough outs.

James Mellaart suggested the industry dated to a period before the Pottery Neolithic at Byblos (10,600 to 6900 BCE according to the ASPRO chronology) and noted “Aceramic cultures have not yet been found in excavations but they must have existed here as it is clear from Ras Shamra and from the fact that the Pre-Pottery B complex of Palestine originated in this area, just as the following Pottery Neolithic cultures can be traced back to the Lebanon.”

A notable stratified excavation of Heavy Neolithic material took place in 1963 at Adloun II (Bezez Cave), conducted by Diana Kirkbride and Dorothy Garrod, who determined a sequence stretching through the Yarbrudian, Levalloiso-Mousterian, Upper Paleolithic and on into the Heavy Neolithic. Materials extracted from the upper layers were however disturbed.

The morphology of the tools has noted similarities to the Campignian industry in France, an archaeological culture of the early Neolithic period (sixth millennium to fourth millennium B.C.) in France, named after the Campigny site in the department of Seine-Maritime. The concept of the Campignian culture was introduced in 1886 by the French archaeologist F. Salmon.

The population of the culture engaged in fishing and hunting for deer, wild horses, and oxen. Much importance was also attached to the gathering of cereal grasses (grain mortars and barley grain impressions in pottery have been discovered), which paved the way for the development of agriculture. The dog was the only domestic animal. Dwellings were round pit houses measuring 6 m in diameter.

Typical stone implements included the tranchet (a triangular chopping tool with a broad cutting edge and a handle attached to the narrow end) and the pick (axmattock, an oval tool with lateral working edges). The tools were used for woodworking (making boats, rafts, weirs). The ax-mattock was also used for digging. Polished axes appeared in later Campignian culture sites. Pottery—flat-bottomed and pointed-bottomed vessels made of clay mixed with sand and crushed shells—was made for the first time in the Campignian culture.

The industry has been found at surface stations in the Beqaa Valley and on the seaward side of the mountains. Heavy Neolithic sites were found near sources of flint and were thought to be factories or workshops where large, coarse flint tools were roughed out to work and chop timber. Chisels, flake scrapers and picks were also found with little, if any sign of arrowheads, sickles (except for Orange slices) or pottery.

Finds of waste and debris at the sites were usually plentiful, normally consisting of Orange slices, thick and crested blades, discoid, cylindrical, pyramidal or Levallois cores. Andrew Moore suggested that many of the sites were used as flint factories that complimented settlements in the surrounding hills.

The identification of Heavy Neolithic sites in Lebanon was complicated by the fact that the assemblages found at these sites included tools made with all techniques used during earlier periods. Bifaces are found both with and without a cortex, along with grattoir de cote, triangular flakes, tortoise cores, discoid cores and steep scrapers.

This presented particular problems with sites where Heavy Neolithic material was mixed with that from the Lower Paleolithic and Middle Paleolithic, such as at Mejdel Anjar I and Dakoue.

Although tools similar to Heavy Neolithic ones were found at later Neolithic surfaces sites, little relationship could be established between those found at the later Neolithic tells, where flints were often sparse, especially at those of later dates.

The relationship and dividing line between the related Shepherd Neolithic zone of the north Bekaa Valley could also not be clearly defined but was suggested to be in the area around Douris and Qalaat Tannour. Not enough exploration has been carried out yet to conclude whether the bands of Neolithic surface sites continues north into the areas around Zahle and Rayak.

Finds of large quantities of seeds and a grinding stone at the paleolithic site of Ohalo II in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee, dated to around 19,400 BP has shown some of the earliest evidence for advanced planning of plant food consumption and has led Ehud Weiss, an archeologist, to suggest that humans at Ohalo II processed the grain before consumption.

Tell Aswad, a large prehistoric, neolithic tell, about 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) in size, located around 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Damascus in Syria, on a tributary of the Barada River at the eastern end of the village of Jdeidet el Khass, is oldest site of agriculture with domesticated emmer wheat dated by Willem van Zeist and his assistant Johanna Bakker-Heeres to 8800 BC.

Tell Aswad has been cited as being of importance for the evolution of organised cities due to the appearance of building materials, organized plans and collective work. It has provided insight into the “explosion of knowledge” in the northern Levant during the PPNB Neolithic stage following dam construction. Aswad has been suggested to be amongst the ten probable centers for the origin of agriculture.

Sue Colledge gives dates for the earliest domesticated cereal use at Tell Aswad from approximately 9150 to 8950 BCE. This is preceded by an earlier and smaller cave site called Iraq ed-Dubb in Jordan showing evidence of domestic cereals possibly as far back as 9600 BCE.

Jacques Cauvin clarifies that Aswad was not the center for the origin of agriculture, stating that its first inhabitants “arrived, perhaps from the neighboring Anti-Lebanon, already equipped with the seeds for planting, for their practice of agriculture from the inception of the settlement is not in doubt. Thus it was not in the oasis itself that they carried out their first experiments in farming.”

Soon after came hulled, two-row barley found domesticated earliest at Jericho in the Jordan valley and Iraq ed-Dubb in Jordan. Other sites in the Levantine corridor that show the first evidence of agriculture include Wadi Faynan 16 and Netiv Hagdud. Jacques Cauvin noted that the settlers of Aswad did not domesticate on site, but “arrived, perhaps from the neighbouring Anti-Lebanon, already equipped with the seed for planting”.

The Heavy Neolithic Qaraoun culture has been identified at around fifty sites in Lebanon around the source springs of the River Jordan, however the dating of the culture has never been reliably determined.

The Qaraoun culture is a culture of the Lebanese Stone Age around Qaraoun in the Beqaa Valley. The Gigantolithic or Heavy Neolithic flint tool industry of this culture was recognized as a particular Neolithic variant of the Lebanese highlands by Henri Fleisch, who collected over one hundred flint tools within two hours on 2 September 1954 from the site. Fleisch discussed the discoveries with Alfred Rust and Dorothy Garrod, who confirmed the culture to have Neolithic elements. Garrod said that the Qaraoun culture “in the absence of all stratigaphical evidence may be regarded as mesolithic or proto-neolithic”.

Due to the disturbance of the upper layers and lack of radiocarbon dating or the materials at the time of this excavation, the placement of the Qaroun culture into the chronology of the ancient Near East remains undetermined from these excavations.

Shepherd Neolithic is a name given by archaeologists to a style (or industry) of small flint tools from the Hermel plains in the north Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. It was determined to be definitely later than the Mesolithic but without any usual forms from the Upper Paleolithic or pottery Neolithic. Henri Fleisch tentatively suggested the industry to be Epipaleolithic and suggested it may have been used by nomadic shepherds. The Shepherd Neolithic has largely been ignored and understudied following the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war.

Pre Pottery Neolithic A

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage in early Levantine Neolithic culture, dating around 8000 to 7000 BC. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was not in use yet. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).

PPNA archaeological sites are much larger than those of the preceding Natufian hunter-gatherer culture, and contain traces of communal structures, such as the famous tower of Jericho.

PPNA settlements are characterized by round, semi-subterranean houses with stone foundations and terrazzo-floors. The upper walls were constructed of unbaked clay mudbricks with plano-convex cross-sections. The hearths were small, and covered with cobbles. Heated rocks were used in cooking, which led to an accumulation of fire-cracked rock in the buildings, and almost every settlement contained storage bins made of either stones or mud-brick.

One of the most notable PPNA settlements is Jericho, thought to be the world’s first town (c 8000 BC). The PPNA town contained a population of up to 2,000-3,000 people, and was protected by a massive stone wall and tower. There is much debate over the function of the wall, for there is no evidence of any serious warfare at this time. One possibility is the wall was built to protect the salt resources of Jericho.

PPNA cultures are unique for their burial practices, and Kenyon (who excavated the PPNA level of Jericho), characterized them as “living with their dead”. Kenyon found no fewer than 279 burials, below floors, under household foundations, and in between walls. In the PPNB period, skulls were often dug up and reburied, or mottled with clay and (presumably) displayed.

The lithic industry is based on blades struck from regular cores. Sickle-blades and arrowheads continue traditions from the late Natufian culture, transverse-blow axes and polished adzes appear for the first time.

Sedentism of this time allowed for the cultivation of local grains, such as barley and wild oats, and for storage in granaries. Sites such as Dhra′ and Jericho retained a hunting lifestyle until the PPNB period, but granaries allowed for year-round occupation.

This period of cultivation is considered “pre-domestication”, but may have begun to develop plant species into the domesticated forms they are today. Deliberate, extended-period storage was made possible by the use of “suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents”. This practice “precedes the emergence of domestication and large-scale sedentary communities by at least 1,000 years”.

Granaries are positioned in places between other buildings early on 9500 BC. However beginning around 8500 BC, they were moved inside houses, and by 7500 BC storage occurred in special rooms.

This change might reflect changing systems of ownership and property as granaries shifted from a communal use and ownership to become under the control of households or individuals.

It has been observed of these granaries that their “sophisticated storage systems with subfloor ventilation are a precocious development that precedes the emergence of almost all of the other elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic package—domestication, large scale sedentary communities, and the entrenchment of some degree of social differentiation”.

Moreover, “Building granaries may … have been the most important feature in increasing sedentism that required active community participation in new life-ways”.

Hurrians

Mezine is a place in the Ukraine having the most artifacts from the Paleolithic culture. The epigravettian site is located on a bank of the Desna river. The settlement is best known for an archaeological small find of a set of bracelets, engraved with marks considered as being possibly calendar lunar-cycles. Near to Mezine was found the earliest known example of a swastika-like form, as part of a decorative object, found on an artifact dated to 10,000 BC.

It has been suggested this swastika is a stylized picture of a stork in flight. In Armenian mythology Aragil, or Stork, is considered as the messenger of Ara the Beautiful, their main god, as well as the defender of fields. According to ancient mythological conceptions, two stork symbolize the sun. Ara the Beautiful is the god of spring, flora, agriculture, sowing and water. He is associated with Osiris, Vishnu and Dionysus, as the symbol of new life.

Ceramic production appeared in the ancient Near East towards the end of the 8th millenium BCE, and towards the 6th millenium BCE painted ceramics were common. In southern Mesopotamia the Samarra culture, and in northern Mesopotamia the Hassuna and Samarra cultures, produced finely decorated ceramics in the seventh and early 6th centuries BCE, showing the distribution of Halaf and early Ubaid cultures.

The Hurrians (Ḫu-ur-ri) were a people in Anatolia and Northern Mesopotamia. They spoke an ergative-agglutinative language conventionally called Hurrian, which is unrelated to neighbouring Semitic or Indo-European languages, and may have been a language isolate.

Diakonoff and S. Starostin, the Hurrian and Urartian languages are related to the Northeast Caucasian languages. The Alarodian languages are a proposed language family that encompasses the Northeast Caucasian (Nakh–Dagestanian) languages and the extinct Hurro-Urartian languages.

Urartian, Vannic, and (in older literature) Chaldean (Khaldian, or Haldian) are conventional names for the language spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu that was located in the region of Lake Van, with its capital near the site of the modern town of Van, in the Armenian Highland, modern-day Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. It was probably spoken by the majority of the population around Lake Van and in the areas along the upper Zab valley.

Urartian is closely related to Hurrian, a somewhat better documented language attested for an earlier, non-overlapping period, approximately from 2000 BCE to 1200 BCE (written by native speakers until about 1350 BCE). The two languages must have developed quite independently from approximately 2000 BCE onwards.

Although Urartian is not a direct continuation of any of the attested dialects of Hurrian, many of its features are best explained as innovative developments with respect to Hurrian as we know it from the preceding millennium. The closeness holds especially true of the so-called Old Hurrian dialect, known above all from Hurro-Hittite bilingual texts.

The Proto-Northeast Caucasian language had many terms for agriculture, and Johanna Nichols has suggested that its speakers may have been involved in the development of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent. They had words for concepts such as yoke, as well as fruit trees such as apple and pear that suggest agriculture was already well developed when the proto-language broke up.

Hurrian names occur sporadically in northwestern Mesopotamia and the area of Kirkuk in modern Iraq. Their presence was attested at Nuzi, Urkesh and other sites. They occupied a broad arc of fertile farmland stretching from the Khabur River valley in the west to the foothills of the Zagros Mountains in the east.

The Khabur River valley was the heart of the Hurrian lands. This region hosted rich cultures like Tell Halaf and Tell Brak. I. J. Gelb and E. A. Speiser believed Semitic Subarians had been the linguistic and ethnic substratum of northern Mesopotamia since earliest times, while Hurrians were merely late arrivals. However, it now seems that the Subarians was Hurrians.

Gobekli Tepe

As a child, Klaus Schmidt used to grub around in caves in his native Germany in the hope of finding prehistoric paintings. Thirty years later, representing the German Archaeological Institute, he found something infinitely more important — a temple complex almost twice as old as anything comparable on the planet.

“This place is a supernova”, says Schmidt, standing under a lone tree on a windswept hilltop 35 miles north of Turkey’s border with Syria. “Within a minute of first seeing it I knew I had two choices: go away and tell nobody, or spend the rest of my life working here.”

Behind him are the first folds of the Anatolian plateau. Ahead, the Mesopotamian plain, like a dust-colored sea, stretches south hundreds of miles to Baghdad and beyond. The stone circles of Gobekli Tepe are just in front, hidden under the brow of the hill.

Compared to Stonehenge, Britain’s most famous prehistoric site, they are humble affairs. None of the circles excavated (four out of an estimated 20) are more than 30 meters across. What makes the discovery remarkable are the carvings of boars, foxes, lions, birds, snakes and scorpions, and their age.

Dated at around 9,500 BC, these stones are 5,500 years older than the first cities of Mesopotamia, and 7,000 years older than Stonehenge. Never mind circular patterns or the stone-etchings, the people who erected this site did not even have pottery or cultivate wheat. They lived in villages. But they were hunters, not farmers.

“Everybody used to think only complex, hierarchical civilizations could build such monumental sites, and that they only came about with the invention of agriculture”, says Ian Hodder, a Stanford University Professor of Anthropology, who, since 1993, has directed digs at Catalhoyuk, Turkey’s most famous Neolithic site. “Gobekli changes everything. It’s elaborate, it’s complex and it is pre-agricultural. That fact alone makes the site one of the most important archaeological finds in a very long time.”

With only a fraction of the site opened up after a decade of excavations, Gobekli Tepe’s significance to the people who built it remains unclear. Some think the site was the center of a fertility rite, with the two tall stones at the center of each circle representing a man and woman.

Schmidt is skeptical about the fertility theory. He agrees Gobekli Tepe may well be “the last flowering of a semi-nomadic world that farming was just about to destroy,” and points out that if it is in near perfect condition today, it is because those who built it buried it soon after under tons of soil, as though its wild animal-rich world had lost all meaning.

But the site is devoid of the fertility symbols that have been found at other Neolithic sites, and the T-shaped columns, while clearly semi-human, are sexless. “I think here we are face to face with the earliest representation of gods”, says Schmidt, patting one of the biggest stones.

“They have no eyes, no mouths, no faces. But they have arms and they have hands. They are makers. “In my opinion, the people who carved them were asking themselves the biggest questions of all,” Schmidt continued. “What is this universe? Why are we here?”

With no evidence of houses or graves near the stones, Schmidt believes the hill top was a site of pilgrimage for communities within a radius of roughly a hundred miles. He notes how the tallest stones all face southeast, as if scanning plains that are scattered with archeological sites in many ways no less remarkable than Gobekli Tepe.

Last year, for instance, French archaeologists working at Djade al-Mughara in northern Syria uncovered the oldest mural ever found. “Two square meters of geometric shapes, in red, black and white – a bit like a Paul Klee painting,” explains Eric Coqueugniot, the University of Lyon archaeologist who is leading the excavation.

Coqueugniot describes Schmidt’s hypothesis that Gobekli Tepe was meeting point for feasts, rituals and sharing ideas as “tempting,” given the site’s spectacular position. But he emphasizes that surveys of the region are still in their infancy. “Tomorrow, somebody might find somewhere even more dramatic.”

Director of a dig at Korpiktepe, on the Tigris River about 120 miles east of Urfa, Vecihi Ozkaya doubts the thousands of stone pots he has found since 2001 in hundreds of 11,500 year-old graves quite qualify as that. But his excitement fills his austere office at Dicle University in Diyarbakir.

“Look at this”, he says, pointing at a photo of an exquisitely carved sculpture showing an animal, half-human, half-lion. “It’s a sphinx, thousands of years before Egypt. Southeastern Turkey, northern Syria – this region saw the wedding night of our civilization.”

Pre Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is a division of the Neolithic developed by Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the southern Levant region.

Cultural tendencies of this period differ from that of the earlier Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period in that people living during this period began to depend more heavily upon domesticated animals to supplement their earlier mixed agrarian and hunter-gatherer diet. In addition the flint tool kit of the period is new and quite disparate from that of the earlier period. One of its major elements is the naviform core.

This is the first period in which architectural styles of the southern Levant became primarily rectilinear; earlier typical dwellings were circular, elliptical and occasionally even octagonal. Pyrotechnology was highly developed in this period.

During this period, one of the main features of houses is evidenced by a thick layer of white clay plaster floors highly polished and made of lime produced from limestone. It is believed that the use of clay plaster for floor and wall coverings during PPNB led to the discovery of pottery.

The earliest proto-pottery was White Ware vessels, made from lime and gray ash, built up around baskets before firing, for several centuries around 7000 BC at sites such as Tell Neba’a Faour (Beqaa Valley).

Sites from this period found in the Levant utilizing rectangular floor plans and plastered floor techniques were found at Ain Ghazal, Yiftahel (western Galilee), and Abu Hureyra (Upper Euphrates). The period is dated to between ca. 10,700 and ca. 8,000 BP or 7000 – 6000 BCE.

Danielle Stordeur’s recent work at Tell Aswad, a large agricultural village between Mount Hermon and Damascus could not validate Henri de Contenson’s earlier suggestion of a PPNA Aswadian culture. Instead, they found evidence of a fully established PPNB culture at 8700 BC at Aswad, pushing back the period’s generally accepted start date by 1,200 years.

Similar sites to Tell Aswad in the Damascus Basin of the same age were found at Tell Ramad and Tell Ghoraifé. How a PPNB culture could spring up in this location, practicing domesticated farming from 8700 BC has been the subject of speculation.

Whether it created its own culture or imported traditions from the North East or Southern Levant has been considered an important question for a site that poses a problem for the scientific community.

Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Earlier Natufian but shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of north eastern Anatolia.

The culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BC, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries.

In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of Ghassulian culture.

Tell Halaf

In the period 6500–5500 B.C., a farming society emerged in northern Mesopotamia and Syria which shared a common culture and produced pottery that is among the finest ever made in the Near East. This culture is known as Halaf, after the site of Tell Halaf in northeastern Syria where it was first identified.

The Halaf culture is a prehistoric period which lasted between about 6100 and 5500 BC. The period is a continuous development out of the earlier Pottery Neolithic and is located primarily in the Euphrates valley in south-eastern Turkey, the Balikh valley and the Khabur in Syria, and the Upper Tigris area in Iraq, although Halaf-influenced material is found throughout Greater Mesopotamia.

The term «Proto-Halaf period» refers to the gradual emergence of the Halaf culture. It reformulates the «Halafcultural package» as this has been traditionally understood, and it shows that the Halaf emerged rapidly, but gradually, at the end of 7000 BC.

The term refers to a distinct ceramic assemblage characterised by the introduction of painted Fine Ware within the later Pre-Halafceramic assemblage. Although these new wares represent changes in ceramic technology and production, other cultural aspects continue without abrupt change.

The recent discoveries at various Late Neolithic sites in Syrian and elsewhere that have been reviews here are really changing the old, traditional schemes, which often presupposed abrupt transitions from one culture-historical entity to another. At present, there is growing evidence for considerable continuity during 7000-6000 BC.

At the northern Syrian sites, where theProto-Halaf stage was first defined,there is no perceptible break and at several sites (Tell Sabi Abyad, Tell Halula) the Proto-Halaf ceramic assemblage appears tobe closely linked to the preceding late Pre-Halaf.

The key evidence for the Proto-Halaf period is the appearance of new ceramic categories that did not existed before, manufactured according to high technological standards and complexly decorated.

The similarities of these new painted wares from one Proto-Halafsiteto another points to strong relationships between different communities. On the other hand, the evidence oflocal variety in ceramic production would indicate acertain level of independence of local groups.

Although this new stage deservesto be studied much more, it appears to be the case that apart from the ceramicsmost other aspects of the material culture show a gradual, not abrupt evolution from the precedent stage, such as the production of lithic tools, property markers such as stamp seals, the architecture and burial practices.

The discovery of Proto-Halaf layers at Tell Halula, Tell Sabi Abyad and Tell Chagar Bazar has added much insight into the origins of the Halaf and its initial development, and shows that the Halaf resulted from a gradual, continuous process of cultural change. It also seems to be clear that the origins of the Halaf were regionally heterogeneous.

The Halaf culture as it is traditionally understood appears to have evolved over a very large area, which comprises the Euphrates valley (until recently considered to be a peripheral area), the Balikh valley and the Khabur in Syria but also northern Iraq, southern Turkey and the Upper Tigris area.

The Halaf potters used different sources of clay from their neighbors and achieved outstanding elaboration and elegance of design with their superior quality ware. Some of the most beautifully painted polychrome ceramics were produced toward the end of the Halaf period. This distinctive pottery has been found from southeastern Turkey to Iran, but may have its origins in the region of the River Khabur (modern Syria).

How and why it spread so widely is a matter of continuing debate, although analysis of the clay indicates the existence of production centers and regional copying. It is possible that such high-quality pottery was exchanged as a prestige item between local elites.

The Halaf culture also produced a great variety of amulets and stamp seals of geometric design, as well as a range of largely female terracotta figurines that often emphasize the sexual features.

Tell Arpachiyah

The best known, most characteristic pottery of Tell Halaf, called Halaf ware, produced by specialist potters, has been found in other parts of northern Mesopotamia, such as at Nineveh and Tepe Gawra, Chagar Bazar and at many sites in Anatolia (Turkey) suggesting that it was widely used in the region.

Among the best-known Halaf sites are Arpachiyah, Sabi Abyad, and Yarim Tepe, small agricultural villages with distinctive buildings known as tholoi. These rounded domed structures, with or without antechambers, were made of different materials depending on what was available locally: limestone boulders or mud and straw.

The most important site for the Halaf tradition was the site of Tell Arpachiyah located about 4 miles from Nineveh, now located in the suburbs of Mosul, Iraq. The site was occupied in the Halaf and the following Ubaid periods. It appears to have been heavily involved in the manufacture of pottery. The pottery recovered there formed the basis of the internal chronology of the Halaf period.

Early in the chalcolithic period the potters of Arpachiyah in the Khabur Valley carried on the Tell Halaf tradition with a technical ability and with a sense of artistry far superior to that attained by the earlier masters; their polychrome designs, executed in rous paint, show a richness of invention and a painstaking skill in draughtsmanship which is unrivaled in the ancient world.

Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra have produced typical Eastern Halaf ware while a rather different Western Halaf version is known from such Syrian sites as Carchemish and Halaf itself.

The swastika

The Halaf culture, which existed just before and during the Ubaid period at around the same time, had Swastikas on their pottery and other items. These people eventually gave rise to the ancient Samarra culture and the Sumerians, who also used the Swastika symbol. The ancient Vinca culture (5500 BC) was the first appearance of the swastika in history, not what you’re reading above. The Tartaria culture of Romainia (4000 BC) had similar symbols.

Then later the Merhgarh Culture, which later became the Harappan culture of the Great Indus Valley Civilization (which is where “The Vedas” came from) also exhibited the Swastika symbolism. Then even later the legendary Xia Dynasty held the swastika symbol in high regard. Even ancient Native American Indians knew this symbol. If you’ve noticed all these cultures were exactly 1000 years apart, bringing the Swastika symbol west to east from the Balkans to China and even beyond. Look it up, do the research.

It seems that there is a connection between the similar sounding places of ‘Samarra’ and ‘Sumeru’, and that early travellers bring the Swastika to India and settle on mount Sumeru – naming the new place after their place of origination. Over-time, ‘Samarra’ could have changed in pronounciation to ‘Sumeru’.

Tell Hassuna

Hassuna or Tell Hassuna is an ancient Mesopotamian site situated in what was to become ancient Assyria, and is now in the Ninawa Governorate of Iraq west of the Tigris river, south of Mosul and about 35 km southwest of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh.

By around 6000 BC people had moved into the foothills (piedmont) of northernmost Mesopotamia where there was enough rainfall to allow for “dry” agriculture in some places. These were the first farmers in northernmost Mesopotamia. They made Hassuna style pottery (cream slip with reddish paint in linear designs). Hassuna people lived in small villages or hamlets ranging from 2 to 8 acres (32,000 m2).

At Tell Hassuna, adobe dwellings built around open central courts with fine painted pottery replace earlier levels with crude pottery. Hand axes, sickles, grinding stones, bins, baking ovens and numerous bones of domesticated animals reflect settled agricultural life. Female figurines have been related to worship and jar burials within which food was placed related to belief in afterlife. The relationship of Hassuna pottery to that of Jericho suggests that village culture was becoming widespread.

Shulaveri-Shomu culture

Shulaveri-Shomu culture is a Late Neolithic/Eneolithic culture that existed on the territory of present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Armenian Highlands. The culture is dated to mid-6th or early-5th millennia BC and is thought to be one of the earliest known Neolithic cultures.

The Shulaveri-Shomu culture begins after the 8.2 kiloyear event which was a sudden decrease in global temperatures starting ca. 6200 BC and which lasted for about two to four centuries.

Shulaveri culture predates the Kura-Araxes culture and surrounding areas, which is assigned to the period of ca. 4000 – 2200 BC, and had close relation with the middle Bronze Age culture called Trialeti culture (ca. 3000 – 1500 BC). Sioni culture of Eastern Georgia possibly represents a transition from the Shulaveri to the Kura-Arax cultural complex.

Shulaveri-Shomu and other Neolithic/Chalcolithic cultures of the Southern Caucasus started to use local obsidian for tools, raise animals such as cattle and pigs, and grow crops, including grapes around 6000–4200 BC.

Many of the characteristic traits of the Shulaverian material culture (circular mudbrick architecture, pottery decorated by plastic design, anthropomorphic female figurines, obsidian industry with an emphasis on production of long prismatic blades) are believed to have their origin in the Near Eastern Neolithic cultures, like Tell Halaf and Tell Hassuna.

The Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period

The Halaf period was succeeded by the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period (ca. 5500/5400 to 5200/5000 BC) and then by the Ubaid period (~5200 – 4000 cal. BC). The Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period lies chronologically between the Halaf period and the Ubaid period.

It is a very poorly understood period and was created to explain the gradual change from Halaf style pottery to Ubaid style pottery in North Mesopotamia. ArchaeologyArchaeologically the period is defined more by absence then data as the Halaf appears to have ended before 5500/5400 cal. BC and the Ubaid begins after 5200 cal. BC.

There are only two sites that run from the Halaf until the Ubaid. The first of these, Tepe Gawra, was excavated in the 1930s when stratigraphic controls were lacking and it is difficult to re-create the sequence. The second, Tell Aqab remains largely unpublished.

This makes definitive statements about the period difficult and with the present state of archaeological knowledge nothing certain can be claimed about the Halaf-Ubaid transitional except that it is a couple of hundred years long and pottery styles changed over the period.

Hadji Muhammed-Choga Mami-Samarra

Hadji Muhammed was a small village in Southern Iraq which gives its name to a style of painted pottery and the early phase of what is the Ubaid culture. Sandwiched between the earliest settlement of Eridu and the later “classical” Ubaid style, the culture is found as far north as Ras Al-Amiya. The Hadji Muhammed period saw the development of extensive canal networks from major settlements.

Irrigation agriculture, which seem to have developed first at Choga Mami (4700–4600 BC), a Samarra ware archaeological site of Southern Iraq in the Mandali region which shows the first canal irrigation in operation at about 6000 BCE, and rapidly spread elsewhere, from the first required collective effort and centralised coordination of labour. Buildings were of wattle and daub or mud brick.

The Samarran Culture, the precursor to the Mesopotamian culture of the Ubaid period, is primarily known for its finely-made pottery decorated against dark-fired backgrounds with stylized figures of animals and birds and geometric designs. This widely-exported type of pottery, one of the first widespread, relatively uniform pottery styles in the Ancient Near East, was first recognized at Samarra.

The pottery is painted in dark brown, black or purple in an attractive geometric style. Joan Oates has suggested on the basis of continuity in configurations of certain vessels, despite differences in thickness of others that it is just a difference in style, rather than a new cultural tradition.

Tell Ubaid

The Halaf culture was eventually absorbed into the so-called Ubaid culture (ca. 6500 to 3800 BC), a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia with changes in pottery and building styles. The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughoutMesopotamia and the Persian Gulf.

The Ubaid period derive it’s name from the tell (mound) of al-Ubaid west of nearby Ur in southern Iraq’s Dhi Qar Governorate where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvium although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.

The Ubaidians were the first civilizing force in Sumer, draining the marshes for agriculture, developing trade, and establishing industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery. It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture.

During this time, the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was established at Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI), ca. 5300 BC, by farmers who brought with them the Hadji Muhammed culture, which first pioneered irrigation agriculture. It appears this culture was derived from the Samarran culture from northern Mesopotamia.

Eridu remained an important religious center when it was gradually surpassed in size by the nearby city of Uruk. The story of the passing of the me (gifts of civilisation) to Inanna, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect this shift in hegemony.

In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

The Ghassulian culture

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant. The Ghassulians were a Chalcolithic culture as they also smelted copper.

Considered to correspond to the Halafian culture, Tell Hassuna and Tell Ubaid of North Syria and Mesopotamia, its type-site, Tulaylat al-Ghassul, is located in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea in modern Jordan and was excavated in the 1930s.

The dates for Ghassulian are dependent upon 14C (radiocarbon) determinations, which suggest that the typical later Ghassulian began sometime around the mid-5th millennium and ended ca. 3800 BC. The transition from Late Ghassulian to EB I seems to have been 3800-3500 BC.

Funerary customs show evidence that they buried their dead in stone dolmens, a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of three or more upright stones supporting a large flat horizontal capstone (table), although there are also more complex variants. Most date from the early Neolithic period (4000 to 3000 BC).

The Ghassulian culture, that has been identified at numerous other places in what is today southern Israel, especially in the region of Beersheba, correlates closely with the Amratian (Naqada I) and Gerzeh (Naqada II) cultures, which brought a number of technological improvements, of Egypt and may have had trading affinities (e.g., the distinctive churns, or “bird vases”) with early Minoan culture in Crete.

Egypt

The Amratian Culture was a cultural period in the history of predynastic Upper Egypt, which lasted approximately from 4000 to 3500 BC. It is named after the site of El-Amra, about 120 km (75 mi) south of Badari, Upper Egypt.

El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found without being mingled with the later Gerzean culture group. However, this period is better attested at the Naqada site, thus it also is referred to as the Naqada I culture.

The Naqada culture manufactured a diverse selection of material goods, reflective of the increasing power and wealth of the elite, as well as societal personal-use items, which included combs, small statuary, painted pottery, high quality decorative stone vases, cosmeti palettes, and jewelry made of gold, lapis, and ivory.

They also developed a ceramic glaze known as faience, which was used well into the Roman Period to decorate cups, amulets, and figurines. During the last predynastic phase, the Naqada culture began using written symbols that eventually were developed into a full system of hieroglyphs for writing the ancient Egyptian language.

In Naqada II times, early evidence exists of contact with the Near East, particularly Canaan and the Byblos coast. Over a period of about 1,000 years, the Naqada culture developed from a few small farming communities into a powerful civilization whose leaders were in complete control of the people and resources of the Nile valley.

Gerzeh, also Girza or Jirzah, is the second of three phases of the Naqada Culture, and so is called Naqada II. It is preceded by the Amratian (Naqada I) and followed by the Protodynastic or Semainian (Naqada III). The end of the Gerzean period is generally regarded as coinciding with the unification of Egypt.

It was a predynastic Egyptian cemetery located along the west bank of the Nile and today named after al-Girza, the nearby present day town in Egypt. Gerzeh is situated only several miles due east of the lake of the Al Fayyum.

Establishing a power center at Hierakonpolis, and later at Abydos, Naqada III leaders expanded their control of Egypt northwards along the Nile. There is also strong archaeological evidence of Egyptian settlements in southern Canaan during the Protodynastic Period, which are regarded as colonies or trading entrepôts.

By about 3600 BC, neolithic Egyptian societies along the Nile River had based their culture on the raising of crops and the domestication of animals. The Mesopotamian process of sun-dried bricks, and architectural building principles—including the use of the arch and recessed walls for decorative effect—became popular during this time.

Shortly after 3600 BC Egyptian society began to grow and advance rapidly toward refined civilization. A new and distinctive pottery, which was related to the pottery of the Southern Levant, appeared during this time. Extensive use of copper became common during this time.

The Gerzean culture, from about 3500 to 3200 BC, is named after the site of Gerzeh. It was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation of Dynastic Egypt was laid.

Gerzean culture is largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt, but failing to dislodge Amratian culture in Nubia.

Gerzean pottery is distinctly different from Amratian white cross-lined wares or black-topped ware. Gerzean pottery was painted mostly in dark red with pictures of animals, people, and ships, as well as geometric symbols that appear derived from animals. Also, “wavy” handles, rare before this period became more common and more elaborate until they were almost completely ornamental.

Although the Gerzean Culture is now clearly identified as being the continuation of the Amratian period, significant amounts of Mesopotamian influences worked their way into Egypt during the Gerzean which were interpreted in previous years as evidence of a Mesopotamian ruling class, the so-called Dynastic Race, coming to power over Upper Egypt. This idea no longer attracts academic support.

Distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt during this period, indicating contacts with several parts of Asia. Objects such as the Gebel el-Arak knife handle, which has patently Mesopotamian relief carvings on it, have been found inEgypt, and the silver which appears in this period can only have been obtained from Asia Minor.

In addition, Egyptian objects are created which clearly mimic Mesopotamian forms, although not slavishly. Cylinder seals appear in Egypt, as well as recessed paneling architecture, the Egyptian reliefs on cosmetic palettes are clearly made in the same style as the contemporary Mesopotamian Uruk culture, and the ceremonial mace heads which turn up from the late Gerzean and early Semainean are crafted in the Mesopotamian “pear-shaped” style, instead of the Egyptian native style.

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but contact with Canaan does not predate the early dynastic, so it is usually assumed to have been by water. During the time when the Dynastic Race Theory was still popular, it was theorized that Uruk sailors circumnavigated Arabia, but a Mediterranean route, probably by middlemen through Byblos is more likely, as evidenced by the presence of Byblian objects in Egypt.

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis which lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then taken to the Red Sea).

Also, it is considered unlikely that something as complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and at least a small contingent of migrants is often suspected.

Concurrent with these cultural advances, a process of unification of the societies and towns of the upper Nile River, or Upper Egypt, occurred. At the same time the societies of the Nile Delta, or Lower Egypt also underwent a unification process. Warfare between Upper and Lower Egypt occurred often.

Hamoukar

Hamoukar is a large archaeological site located in the Jazira region of northeastern Syria near the Iraqi border (Al Hasakah Governorate) and Turkey. The Excavations have shown that this site houses the remains of one of the world’s oldest known cities, leading scholars to believe that cities in this part of the world emerged much earlier than previously thought.

Traditionally, the origins of urban developments in this part of the world have been sought in the riverine societies of southern Mesopotamia (in what is now southern Iraq). This is the area of ancient Sumer, where around 4000 BC many of the famous Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk emerged, giving this region the attributes of “Cradle of Civilization” and “Heartland of Cities.”

Following the discoveries at Hamoukar, this definition may have to extended further up the Tigris River to include that part of northern Syria where Hamoukar is located.

This archaeological discovery suggests that civilizations advanced enough to reach the size and organizational structure that was necessary to be considered a city could have actually emerged before the advent of a written language.

Previously it was believed that a system of written language was a necessary predecessor of that type of complex city. Most importantly, archaeologists believe this apparent city was thriving as far back as 4000 BC and independently from Sumer.

Until now, the oldest cities with developed seals and writing were thought to be Sumerian Uruk and Ubaid in Mesopotamia, which would be in the southern one-third of Iraq today.

The discovery at Hamoukar indicates that some of the fundamental ideas behind cities—including specialization of labor, a system of laws and government, and artistic development – may have begun earlier than was previously believed.

The fact that this discovery is such a large city is what is most exciting to archaeologists. While they have found small villages and individual pieces that date much farther back than Hamoukar, nothing can quite compare to the discovery of this size and magnitude. Discoveries have been made here that have never been seen before, including materials from Hellenistic and Islamic civilizations.

Shengavit

The Shengavit Settlement is an archaeological site in present day Yerevan, Armenia located on a hill south-east of Lake Yerevan. It was inhabited during a series of settlement phases from approximately 3200 BC cal to 2500 BC cal in the Kura Araxes (Shengavitian) Period of the Early Bronze Age and irregularly re-used in the Middle Bronze Age until 2200 BC cal. Its pottery makes it a type site of the Kura-Araxes or Early Transcaucasian Period and the Shengavitian culture area.

Archaeologists so far have uncovered large cyclopean walls with towers that surrounded the settlement. Within these walls were circular and square multi-dwelling buildings constructed of stone and mud-brick. Inside some of the residential structures were ritual hearths and household pits, while large silos located nearby stored wheat and barley for the residents of the town. There was also an underground passage that led to the river from the town.

A large stone obelisk was discovered in one of the structures during earlier excavations. A similar obelisk was uncovered at the site of Mokhrablur four km south of Ejmiatsin. It is thought that this, and the numerous statuettes made of clay that have been found are part of a central ritualistic practice in Shengavit.

Pottery found at the town typically has a characteristic black burnished exterior and reddish interior with either incised or raised designs. This style defines the period, and is found across the mountainous Early Transcaucasian territories. One of the larger styles of pottery has been identified as a wine vat but residue tests will confirm this notion.

A popular press source unfortunately has been cited misstating information from a 2010 press conference in Yerevan. In that conference Rothman described the Uruk Expansion trading network, and the likelihood that raw materials and technologies from the South Caucasus had reached the Mesopotamian homeland, which somehow was misinterpreted to say that Armenian culture was a source of Mesopototamian culture, which is not true. The Kura Araxes (Shengavitian) cultures and societies are a unique mountain phenomenon, evolved parallel to but not the same as Mesopotamian cultures.

There is evidence of trade between the Kura Araxes culture and Mesopotamia, as well as Asia Minor. It is, however, considered above all to be indigenous to the Caucasus, and its major variants characterized later major cultures in the region.

Their pottery was distinctive; in fact, the spread of their pottery along trade routes into surrounding cultures was much more impressive than any of their achievements domestically. It was painted black and red, using geometric designs for ornamentation.

Examples have been found as far south as Syria and Israel, and as far north as Dagestan and Chechnya. Their metal goods were widely distributed, recorded in the Volga, Dnieper and Don-Donets systems in the north, into Syria and Palestine in the south, and west into Anatolia.

The spread of this pottery, along with archaeological evidence of invasions, suggests that the Kura-Araxes people may have spread outward from their original homes, and most certainly, had extensive trade contacts. Jaimoukha believes that its southern expanse is attributable primarily to Mitanni and the Hurrians.

Inhumation practices are mixed. Flat graves are found, but so are substantial kurgan burials, the latter of which may be surrounded by cromlechs. This points to a heterogeneous ethno-linguistic population.

Late in the history of this culture, its people built kurgans of greatly varying sizes, containing greatly varying amounts and types of metalwork, with larger, wealthier kurgans surrounded by smaller kurgans containing less wealth. They are also remarkable for the production of wheeled vehicles (wagons and carts), which were sometimes included in burial kurgans. This trend suggests the eventual emergence of a marked social hierarchy.

It has been uncovered pre-Kura-Araxes/Late Chalcolithic materials from the settlement of Boyuk Kesik and the kurgan necropolis of Soyuq Bulaq in northwestern Azerbaijan, and Makharadze has also excavated a pre-Kura-Araxes kurgan, Kavtiskhevi, in central Georgia.

Materials recovered from both these recent excavations can be related to remains from the metal-working Late Chalcolithic site of Leilatepe on the Karabakh steppe near Agdam and from the earliest level at the multi-period site of Berikldeebi in Kvemo Kartli. They reveal the presence of early 4th millennium raised burial mounds or kurgans in the southern Caucasus.

Similarly, on the basis of surveys in eastern Anatolia north of the Oriental Taurus mountains, the chafffaced wares collected at Hanago in the Sürmeli Plain and Astepe and Colpan in the eastern Lake Van district in northeastern Turkey has been likens with those found at the sites mentioned above and relates these to similar wares (Amuq E/F) found south of the Taurus Mountains in northern Mesopotamia.

The new high dating of the Maikop culture essentially signifies that there is no chronological hiatus separating the collapse of the Chalcolithic Balkan centre of metallurgical production and the appearance of Maikop and the sudden explosion of Caucasian metallurgical production and use of arsenical copper/bronzes.

More than forty calibrated radiocarbon dates on Maikop and related materials now support this high chronology; and the revised dating for the Maikop culture means that the earliest kurgans occur in the northwestern and southern Caucasus and precede by several centuries those of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) cultures of the western Eurasian steppes.

The calibrated radiocarbon dates suggest that the Maikop ‘culture’ seems to have had a formative influence on steppe kurgan burial rituals and what now appears to be the later development of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) culture on the Eurasian steppes.

In other words, sometime around the middle of the 4th millennium BCE or slightly subsequent to the initial appearance of the Maikop culture of the NW Caucasus, settlements containing proto-Kura-Araxes or early Kura-Araxes materials first appear across a broad area that stretches from the Caspian littoral of the northeastern Caucasus in the north to the Erzurum region of the Anatolian Plateau in the west.

For simplicity’s sake these roughly simultaneous developments across this broad area will be considered as representing the beginnings of the Early Bronze Age or the initial stages of development of the KuraAraxes/Early Transcaucasian culture.

While broadly (and somewhat imprecisely) defined the ‘homeland’ (itself a very problematic concept) of the Kura-Araxes culture-historical community might include areas in northeastern Anatolia as far as the Erzurum area, the catchment area drained by the Upper Middle Kura and Araxes Rivers in Transcaucasia and the Caspian corridor and adjacent mountainous regions of northeastern Azerbaijan and southeastern Daghestan. These regions constitute on present evidence the original core area out of which the Kura-Araxes ‘culture-historical community’ emerged.

Kura-Araxes materials found in other areas are primarily intrusive in the local sequences. Indeed, many, but not all, sites in the Malatya area along the Upper Euphrates drainage of eastern Anatolia (e.g., Norsun-tepe, Arslantepe) and western Iran (e.g., Yanik Tepe, Godin Tepe) exhibit – albeit with some overlap – a relatively sharp break in material remains, including new forms of architecture and domestic dwellings, and such changes support the interpretation of a subsequent spread or dispersal from this broadly defined core area in the north to the southwest and southeast.

The archaeological record seems to document a movement of peoples north to south across a very extensive part of the Ancient Near East from the end of the 4th to the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Although migrations are notoriously difficult to document on archaeological evidence, these materials constitute one of the best examples of prehistoric movements of peoples available for the Early Bronze Age.

Hurrian and Urartian elements are quite probable, as are Northeast Caucasian ones. Some authors subsume Hurrians and Urartians under Northeast Caucasian as well as part of the Alarodian theory, a proposed language family that encompasses the Northeast Caucasian (Nakh–Dagestanian) languages and the extinct Hurro-Urartian languages.

The presence of Kartvelian languages was also highly probable. Influences of Semitic languages and Indo-European languages are also highly possible, though the presence of the languages on the lands of the Kura–Araxes culture is more controversial.

Armi

Aleppo has scarcely been touched by archaeologists, since the modern city occupies its ancient site. The site has been occupied from around 5000 BC, as excavations in Tallet Alsauda show. Little of Aleppo has been excavated by archaeologists, since Aleppo was never abandoned during its long history and the modern city is situated above the ancient site. Therefore, most of the knowledge about Yamhad comes from tablets discovered at Alalakh and Mari.

Aleppo appears in historical records as an important city much earlier than Damascus. The first record of Aleppo comes from the third millennium BC, in the Ebla tablets, a collection of as many as 1800 complete clay tablets, 4700 fragments and many thousand minor chips found in the palace archives of the ancient city of Ebla, Syria, when Aleppo was the capital of an independent kingdom closely related to Ebla, known as Armi.

Two languages appeared in the writing on the tablets: Sumerian, and a previously unknown language that used the Sumerian cuneiform script (Sumerian logograms or “Sumerograms”) as a phonetic representation of the locally spoken Ebla language.

The latter script was initially identified as proto-Canaanite by professor Giovanni Pettinato, who first deciphered the tablets, because it predated the Semitic languages of Canaan, like Ugaritic and Hebrew. Pettinato later retracted the designation and decided to call it simply “Eblaite”, the name by which it is known today.

Eblaite is an extinct Semitic language which was used in the 23rd century BC in the ancient city of Ebla. Eblaite has been described as an East Semitic language which may be very close to pre-Sargonic Akkadian.

For example, Manfred Krebernik says that Eblaite “is so closely related to Akkadian that it may be classified as an early Akkadian dialect”, although some of the names that appear in the tablets are Northwest Semitic.

According to Cyrus H. Gordon, although scribes might have spoken it sometimes, Eblaite was probably not spoken much, being rather a written lingua franca with East and West Semitic features.

Armani, Arman or Armanum, was an important Bronze Age city-kingdom during the late third millennium BC located in northern Syria, identified with the city of Aleppo. Aleppo was the capital of the independent kingdom closely related to Ebla, Naram-Sin of Akkad mentions Arman or Armani as a city that he sacked along with Ebla, this Armani was identified by some scholars with Armi.

Naram-Sin of Akkad mention his destruction of Ebla and Armani/Armanum, in the 23rd century BC. Naram-Sin mentions that he captured the king of Arman when he sacked the city. Naram-Sin gives a long description about his siege of armani, his destruction of its walls and the capturing of its king Rid-Adad.

It has been suggested by early 20th century Armenologists that Old Persian Armina and the Greek Armenoi are continuations of an Assyrian toponym Armânum or Armanî. There are certain Bronze Age records identified with the toponym in both Mesopotamian and Egyptian sources. The earliest is from an inscription which mentions Armânum together with Ibla (Ebla) as territories conquered by Naram-Sin of Akkad in ca. 2250 BC.

Subartu

Armani-Subartu (Sumerian: Arme-Shupria) is mentioned in Bronze Age literature from the time of the earliest Mesopotamian records from the mid 3rd millennium BC. It was a Hurrian-speaking kingdom, known from Assyrian sources beginning in the 13th century BC, located in the Armenian Highland, to the southwest of Lake Van, bordering on Ararat proper. Scholars have linked the district in the area called Arme or Armani, to the name Armenia.

Subartu was apparently a polity in Northern Mesopotamia, at the upper Tigris. Most scholars accept Subartu as an early name for Assyria proper on the Tigris, although there are various other theories placing it sometimes a little farther to the east, north or west of there. Its precise location has not been identified.

The Sumerian mythological epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta lists the countries where the “languages are confused” as Subartu, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki (Akkad), and the Martu land (the Amorites).

From the point of view of the Akkadian Empire, Subartu marked the northern geographical horizon, just as Martu, Elam and Sumer marked “west”, “east” and “south”, respectively.

Similarly, the earliest references to the “four quarters” by the kings of Akkad name Subartu as one of these quarters around Akkad, along with Martu, Elam, and Sumer. Subartu in the earliest texts seem to have been farming mountain dwellers, frequently raided for slaves.

Subartu may have been in the general sphere of influence of the Hurrians. There are various alternate theories associating the ancient Subartu with one or more modern cultures found in the region, including Armenian tribes.

Weidner interpreted textual evidence to indicate that after the Hurrian king Shattuara of Mitanni was defeated by Adad-nirari I of Assyria in the early 13th century BC, he then became ruler of a reduced vassal state known as Shubria or Subartu.

Together with Armani-Subartu, Hayasa-Azzi and other populations of the region such as the Nairi fell under Urartian (Kingdom of Ararat) rule in the 9th century BC, and their descendants, according to most scholars, later contributed to the ethnogenesis of the early Armenians.

By the Early Iron Age, the Hurrians had been assimilated with other peoples, except perhaps in the kingdom of Urartu, corresponding to the biblical Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili;), was an Iron Age kingdom centred around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands. According to a hypothesis by I.M.

The Iron Age Urartian language is closely related to or a direct descendant of Hurrian. Several notable Russian linguists, such as S. A. Starostin and V. V. Ivanov, have claimed that Hurrian and Hattic were related to the Northeast Caucasian languages.

In the early 6th century BC, the Urartian Kingdom was replaced by the Armenian Orontid dynasty. In the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 521 or 520 BC by the order of Darius the Great of Persia, the country referred to as Urartu in Assyrian is called Arminiya in Old Persian and Harminuia in Elamite.

Shubria was part of the Urartu confederation. Later, there is reference to a district in the area called Arme or Urme, which some scholars have linked to the name Armenia. Some scholars, such as Harvard Professor Mehrdad Izady, claim to have identified Subartu with the current Kurdish tribe of Zibaris inhabiting the northern ring around Mosul up to Hakkari in Turkey.

The Sumerians

Sumer (from Akkadian Šumeru; Sumerian ki-en-ĝir, approximately “land of the civilized kings” or “native land”) was an ancient civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq, during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age. The Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods.

Although the earliest historical records in the region do not go back much further than ca. 2900 BC, modern historians have asserted that Sumer was first settled between ca. 4500 and 4000 BC by a non-Semitic people who may or may not have spoken the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc. as evidence).

These conjectured, prehistoric people are now called Ubaidians, and are theorized to have evolved from the Chalcolithic Samarra culture (ca 5500–4800 BC) of northern Mesopotamia (Assyria) identified at the rich site of Tell Sawwan, where evidence of irrigation—including flax—establishes the presence of a prosperous settled culture with a highly organized social structure.

It appears that this early culture was an amalgam of three distinct cultural influences: peasant farmers, living in wattle and daub or clay brick houses and practicing irrigation agriculture; hunter-fishermen living in woven reed houses and living on floating islands in the marshes (Proto-Sumerians); and Proto-Akkadian nomadic pastoralists, living in black tents.

The area west and north of the plains of the Euphrates and Tigris also saw the emergence of early complex societies in the much later Bronze Age (about 4000 BC). There is evidence of written culture and early state formation in this northern steppe area, although the written formation of the states relatively quickly shifted its center of gravity into the Mesopotamian valley and developed there. The area is therefore in very many writers been named “The Cradle of Civilization.”

PPNC

The PPNB culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BC, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries.

In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of Ghassulian culture.

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period. Juris Zarins has proposed that pastoral nomadism, or a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, began as a cultural lifestyle in the wake of the climatic crisis of 6200 BC, and spreading Proto-Semitic languages.

This partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon domesticated animals, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing pastoral nomadism spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.

Nomadic pastoralism is a form of pastoralism where livestock are herded in order to find fresh pastures on which to graze following an irregular pattern of movement. This is in contrast with transhumance where seasonal pastures are fixed.

The nomadic pastoralism was a result of the Neolithic revolution. During the revolution, humans began domesticating animals and plants for food and started forming cities. Nomadism generally has existed in symbiosis with such settled cultures trading animal products (meat, hides, wool, cheeses and other animal products) for manufactured items not produced by the nomadic herders. Henri Fleisch tentatively suggested the Shepherd Neolithic industry of Lebanon may date to the Epipaleolithic and that it may have been used by one of the first cultures of nomadic shepherds in the Beqaa valley.

Andrew Sherratt demonstrates that “early farming populations used livestock mainly for meat, and that other applications were explored as agriculturalists adapted to new conditions, especially in the semi‐arid zone.”

Historically nomadic herder lifestyles have led to warrior-based cultures that have made them fearsome enemies of settled people. Tribal confederations built by charismatic nomadic leaders have sometimes held sway over huge areas as incipient state structures whose stability is dependent upon the distribution of taxes, tribute and plunder taken from settled populations.

In the past it was asserted that pastoral nomads left no presence archaeologically but this has now been challenged. Pastoral nomadic sites are identified based on their location outside the zone of agriculture, the absence of grains or grain-processing equipment, limited and characteristic architecture, a predominance of sheep and goat bones, and by ethnographic analogy to modern pastoral nomadic peoples.

Juris Zahrins has proposed that pastoral nomadism began as a cultural lifestyle in the wake of the 6200 BC climatic crisis when Harifian hunter-gatherers fused with Pre-Pottery Neolithic B agriculturalists to produce a nomadic lifestyle based on animal domestication, developing a circum-Arabian nomadic pastoral complex, and spreading Proto-Semitic languages.

The relationship and dividing line between the related Heavy Neolithic zone of the south Beqaa Valley could also not be clearly defined but was suggested to be in the area around Douris and Qalaat Tannour. Not enough exploration had been carried out to conclude whether the bands of Neolithic surface sites continues south into the areas around Zahle and Rayak.

Along with Maqne I, a town and municipality in the Baalbek District of the Beqaa Governorate, Lebanon, Qaa is a type site of the Shepherd Neolithic industry. The site is located 5 miles (8.0 km) north west of the town, north of a path leading from Qaa to Hermel. It was discovered by M. Billaux and the materials recovered were documented by Henri Fleisch in 1966.

The area was lightly cultivated with a thin soil covering the conglomerates. The flints were divided into three groups of a reddish brown, light brown and one that was mostly chocolate and grey colored with a radiant “desert shine”.

It was one of the most important Phoenician cities, and may have been the oldest. From here, and other ports, a great Mediterranean commercial empire was founded.

Armenia

In the study of ancient civilizations Armenia often remained on the sidelines, as if she had not been involved in major historical turnovers. The researchers’ interest was almost always confined to the territory of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. But, naturally the “factor” of Armenia could not be excluded in the formation of ancient civilizations. There is much evidence to prove it. Nevertheless, for one reason or another Armenia, yet, was left out from the list of possible leaders.

There are, of course, scholars who claim that cultural achievements on the Armenian Plateau in such fields as metallurgy, architecture, military science, and winemaking penetrated into Assyria, Palestine, Egypt and the North Caucasus. For example, according to British orientalist and archaeologist G. Childe, in its impressive antiquity and values the culture of the Armenian Plateau can compete with the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia and the Nile Valley.