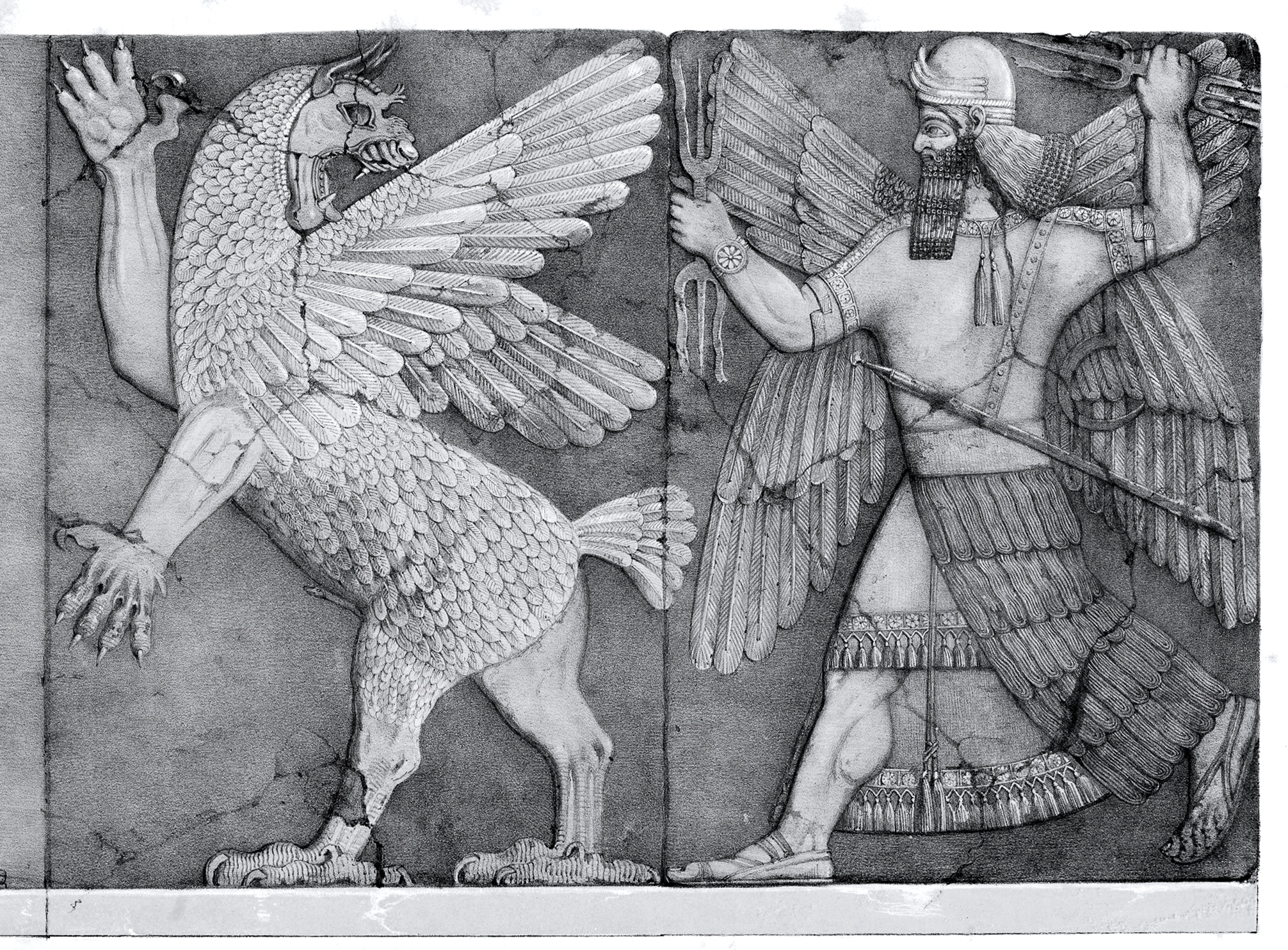

Enlil, wind god, with his thunderbolts pursues Anzu after Anzu stole the Tablets of Destiny (from Austen Henry Layard Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853)

Anu – Enki/Enlil/Haya – Marduk (Sumerian)

Anu – Kumarbi – Teshub (Hurrian)

Anu – El/Dagon – Baal/Haddad/Adad (Semitic)

Uranus – Cronus – Zeus (Greek)

Caelus – Saturn/Janus/Portunus – Jupiter (Roman)

Tefnut/Shu – Ptah/Geb – Nefertem (Egypt)

Nu (the abyss) – Ra/Atum -

Tefnut/Shu – Geb/Nut (Neuth) – Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys and Horus (Egypt)

The trifunctional hypothesis

The trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society postulates a tripartite ideology (“idéologie tripartite”) reflected in the existence of three classes or castes—priests, warriors, and commoners (farmers or tradesmen) – corresponding to the three functions of the sacral, the martial and the economic, respectively.

This thesis is especially associated with the French mythographer Georges Dumézil who proposed it in 1929 in the book Flamen-Brahman, and later in Mitra-Varuna.

Dumézil postulated a split of the figure of the sovereign god in Indoeuropean religion, which is embodied by Vedic gods Varuna and Mitra. Of the two, the first one shows the aspect of the magic, uncanny, awe inspiring power of creation and destruction, while the second shows the reassuring aspect of guarantor of the legal order in organised social life.

Whereas in Jupiter these double features have coalesced, Briquel sees Saturn as showing the characters of a sovereign god of the Varunian type. His nature becomes evident in his mastership over the annual time of crisis around the winter solstice, epitomised in the power of subverting normal codified social order and its rules, which is apparent in the festival of the Saturnalia, in the mastership of annual fertility and renewal, in the power of annihilation present in his paredra Lua, in the fact that he is the god of a timeless era of plenty and bounty before time, which he reinstates at the time of the yearly crisis of the winter solstice.

Also, in Roman and Etruscan reckoning Saturn is a wielder of lightning; no other agricultural god (in the sense of specialized human activity) is one. Hence the mastership he has on agriculture and wealth cannot be that of a god of the third function, i.e. of production, wealth, and pleasure, but it stems from his magical lordship over creation and destruction.

Although these features are to be found in Greek god Cronus as well, it looks they were proper to the most ancient Roman representations of Saturn, such as his presence on the Capitol and his association with Jupiter, who in the stories of the arrival of the Pelasgians in the land of the Sicels and that of the Argei orders human sacrifices to him.

Sacrifices to Saturn were performed according to “Greek rite” (ritus graecus), with the head uncovered, in contrast to those of other major Roman deities, which were performed capite velato, “with the head covered.”

Saturn himself, however, was represented as veiled (involutus), as for example in a wall painting from Pompeii that shows him holding a sickle and covered with a white veil. This feature is in complete accord with the character of a sovereign god of the Varunian type and is common with German god Odin.

Briquel remarks Servius had already seen that the choice of the Greek rite was due to the fact that the god himself is imagined and represented as veiled, thence his sacrifice cannot be carried out by a veiled man: this is an instance of the reversal of the current order of things typical of the nature of the deity as appears in its festival. Plutarch writes his figure is veiled because he is the father of truth.

Pliny notes that the cult statue of Saturn was filled with oil; the exact meaning of this is unclear. Its feet were bound with wool, which was removed only during the Saturnalia. The fact that the statue was filled with oil and the feet were bound with wool may relate back to the myth of “The Castration of Uranus”. In this myth Rhea gives Cronus a rock to eat in Zeus’ stead thus tricking Cronus.

Although mastership of knots is a feature of Greek origin it is also typical of the Varunian sovereign figure, as apparent e.g. in Odin. Once Zeus was victorious over Cronus, he sets this stone up at Delphi and constantly it is anointed with oil and strands of unwoven wool are placed on it. It wore a red cloak, and was brought out of the temple to take part in ritual processions and lectisternia, banquets at which images of the gods were arranged as guests on couches.

All these ceremonial details identify a sovereign figure. Briquel concludes that Saturn was a sovereign god of a time that the Romans perceived as no longer actual, that of the legendary origins of the world, before civilization.

Little evidence exists in Italy for the cult of Saturn outside Rome, but his name resembles that of the Etruscan god Satres. The potential cruelty of Saturn was enhanced by his identification with Cronus, known for devouring his own children. He was thus equated with the Carthaginian god Ba’al Hammon, to whom children were sacrificed.

Later this identification gave rise to the African Saturn, a cult that enjoyed great popularity til the 4th century. It had a popular but also a mysteric character and required child sacrifices. It is also considered as inclining to monotheism.

In the ceremony of initiation the myste intrat sub iugum, ritual that Leglay compares to the Roman tigillum sororium. Even though their origin and theology are completely different the Italic and the African god are both sovereign and master over time and death, fact that has permitted their encounter. Moreover here Saturn is not the real Italic god but his Greek counterpart Cronus.

Saturn was also among the gods the Romans equated with Yahweh, whose Sabbath (on Saturday) he shared as his holy day. The phrase Saturni dies, “Saturn’s day,” first appears in Latin literature in a poem by Tibullus, who wrote during the reign of Augustus.

Theogony

Teshub (also written Teshup or Tešup) was the Hurrian god of sky and storm. Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

The Hurrian myth of Teshub’s origin—he was conceived when the god Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his father Anu’s genital, as such it most likely shares a Proto-Indo-European cognate with the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony.

In ancient myth recorded by Hesiod’s Theogony, Cronus envied the power of his father, the ruler of the universe, Uranus. Uranus drew the enmity of Cronus’ mother, Gaia, when he hid the gigantic youngest children of Gaia, the hundred-handed Hecatonchires and one-eyed Cyclopes, in the Tartarus, so that they would not see the light. Gaia created a great stone sickle and gathered together Cronus and his brothers to persuade them to castrate Uranus.

Only Cronus was willing to do the deed, so Gaia gave him the sickle and placed him in ambush. When Uranus met with Gaia, Cronus attacked him with the sickle, castrating him and casting his testicles into the sea.

From the blood that spilled out from Uranus and fell upon the earth, the Gigantes, Erinyes, and Meliae were produced. The testicles produced the white foam from which the goddess Aphrodite emerged.

For this, Uranus threatened vengeance and called his sons Titenes (according to Hesiod meaning “straining ones,” the source of the word “titan”, but this etymology is disputed) for overstepping their boundaries and daring to commit such an act.

In an alternate version of this myth, a more benevolent Cronus overthrew the wicked serpentine Titan Ophion. In doing so, he released the world from bondage and for a time ruled it justly.

After dispatching Uranus, Cronus re-imprisoned the Hecatonchires, and the Cyclopes and set the dragon Campe to guard them. He and his sister Rhea took the throne of the world as king and queen. The period in which Cronus ruled was called the Golden Age, as the people of the time had no need for laws or rules; everyone did the right thing, and immorality was absent.

Cronus learned from Gaia and Uranus that he was destined to be overcome by his own sons, just as he had overthrown his father. As a result, although he sired the gods Demeter, Hestia, Hera, Hades and Poseidon by Rhea, he devoured them all as soon as they were born to prevent the prophecy.

When the sixth child, Zeus, was born Rhea sought Gaia to devise a plan to save them and to eventually get retribution on Cronus for his acts against his father and children. Another child Cronus is reputed to have fathered is Chiron, by Philyra.

Rhea secretly gave birth to Zeus in Crete, and handed Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, also known as the Omphalos Stone, which he promptly swallowed, thinking that it was his son.

Rhea kept Zeus hidden in a cave on Mount Ida, Crete. According to some versions of the story, he was then raised by a goat named Amalthea, while a company of Kouretes, armored male dancers, shouted and clapped their hands to make enough noise to mask the baby’s cries from Cronus.

Other versions of the myth have Zeus raised by the nymph Adamanthea, who hid Zeus by dangling him by a rope from a tree so that he was suspended between the earth, the sea, and the sky, all of which were ruled by his father, Cronus. Still other versions of the tale say that Zeus was raised by his grandmother, Gaia.

Once he had grown up, Zeus used an emetic given to him by Gaia to force Cronus to disgorge the contents of his stomach in reverse order: first the stone, which was set down at Pytho under the glens of Mount Parnassus to be a sign to mortal men, and then his two brothers and three sisters.

In other versions of the tale, Metis gave Cronus an emetic to force him to disgorge the children, or Zeus cut Cronus’ stomach open. After freeing his siblings, Zeus released the Hecatonchires, and the Cyclopes who forged for him his thunderbolts, Poseidon’s trident and Hades’ helmet of darkness.

In a vast war called the Titanomachy, Zeus and his brothers and sisters, with the help of the Hecatonchires, and Cyclopes, overthrew Cronus and the other Titans. Afterwards, many of the Titans were confined in Tartarus, however, Atlas, Epimetheus, Menoetius, Oceanus and Prometheus were not imprisoned following the Titanomachy. Gaia bore the monster Typhon to claim revenge for the imprisoned Titans.

Accounts of the fate of Cronus after the Titanomachy differ. In Homeric and other texts he is imprisoned with the other Titans in Tartarus. In Orphic poems, he is imprisoned for eternity in the cave of Nyx. Pindar describes his release from Tartarus, where he is made King of Elysium by Zeus.

In another version, the Titans released the Cyclopes from Tartarus, and Cronus was awarded the kingship among them, beginning a Golden Age. In Virgil’s Aeneid, it is Latium to which Saturn (Cronus) escapes and ascends as king and lawgiver, following his defeat by his son Jupiter (Zeus).

One other account referred by Robert Graves (who claims to be following the account of the Byzantine mythographer Tzetzes) it is said that Cronus was castrated by his son Zeus just like he had done with his father Uranus before.

However the subject of a son castrating his own father, or simply castration in general, was so repudiated by the Greek mythographers of that time that they suppressed it from their accounts until the Christian era (when Tzetzes wrote).

The one-handed god and the one-eyed sovereign

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. These closely parallel two ancient Indo-European conceptions of justice represented by the one-eyed sovereign (wild, unreliable, ruling through bravado) and the one-handed sovereign (solemn, proper, ruling by the letter of the law).

These conceptions of justice and their attendant myths were originally described at length by prominent philologist Georges Dumezil (1898-1986) in his 1948 book Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty.

The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

In Nordic mythology, for example, a young wolf named Fenrir is thought (by shrewd prognosticators attuned to supernatural wolf strength) to be capable of destroying the world of the gods. The one-eyed god Odhinn thus tries to get Fenrir to submit to a leash. This he does through deceit: Odhinn presents the leashing as a challenge—see how long it takes you to get out of it. The savvy wolf suspects, correctly, that the leash is magic and will subdue him for eternity. So as a gesture of goodwill, Tyr, a god representing the rule of law, offers to put his hand in Fenrir’s mouth as a pledge to the wolf that there is no hocus-pocus afoot—if Fenrir cannot get out of the leash, Tyr will lose his hand. The wolf submits, the world is saved, but at the cost of Tyr’s hand.

In Roman mytho-history (Romans liked to give their history a mythic burnish), one-eyed Horatio Cocles (“Cocles” being derived from “Cyclops”) and soon to be one-handed Mucius Scaevola team up to defeat Lars Porsenna, an invading Etruscan determined to sack Rome.

According to Dumzeil, the one-eyed Cocles “holds the enemy in check by his strangely wild behavior.” Citing the Roman historian Livy, Dumezil writes that “remaining alone at the entrance to the bridge, [Cocles] casts terrible and menacing looks at the Etruscan leaders, challenging them individually, insulting them collectively.” He also deploys “terrible grimaces.”

Cocles’ antics stop Porsenna temporarily, but the surly Etruscan soon brings war upon Rome again, and this time it’s Scaevola, whose mind ran in a more statesmanlike track than his comrade Cocles, to the rescue. He warns Porsenna that he has 300 assassins at his disposal—it’s a bluff, but Scaevola burns his hand in a fire to convince his enemy his threat is bona fide. Porsenna agrees to leave Rome.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

Dumézil compares Varuna and Mitra with other figures like the gods Savitr (the creative initiater of movement, who is connected with night and dusk) and Bhaga (the fair distributer, who is connected with dawn and midday) of India, the Germanic deities Odin (mystical) and Tyr (prudent), the early Roman kings Romulus (unpredictable founder) and Numa (conservative legislator), and the Irish-Celtic gods Lugus (name derived from proto-Celtic for “oath”) and Nodens (the derivation of this name is uncertain).

A strange motif of unclear meaning involving eyes and hands also plays a role in this concept and extends the metaphor to other figures and stories. While there is nothing particularly significant involving the eyes and hands of Mitra and Varuna (or indeed Romulus and Numa), Odin and Lugus are both one-eyed gods and Tyr and Nodens are both one-handed.

Tyr is probably the oldest of the Germanic deities, his name being an abbreviated form of Tiwaz, which derives from the same PIE word that gave us Zeus, Dios, deus, and theos. Tyr is regarded as the father of the Germanic pantheon while Nodens was the original ruler of the Tuatha de Dannan, a legendary race of people who conquered Ireland from the Fir Bolg. Additionally, two early Roman heroes, Horatius Cocles and Mucius Scaevola, are respectively one-eyed and one-handed.

Zeus seized power from his father Cronos with the assistance of Cyclopes and strange hundred-handed creatures (it is worth noting as well that Cronos governed the world without laws while Zeus provided order; there is a legend that Romulus was killed by leading aristocrats due to his arbitrary rulership and replaced with Numa to bring stability).

In the cases of Cocles and Lugus, their eyes were lost in battle while both Scaevola and Tyr were required to sacrifice their hands to uphold oaths. These early Romans are typically regarded as being at least partially historical, but it seems clear that these ancient legends were superimposed upon the real figures for the purposes of narrative.

Gugalanna

Gu or gud means ox, bull. In Mesopotamian mythology, Gugalanna (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”) was a Sumerian deity as well as the constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies.

Gugalanna was the first husband of the Goddess Ereshkigal, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, a gloomy place devoid of light. It was to share the sorrow with her sister that Inanna later descends to the Underworld.

Taurus was a constellation of the Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox from about 3,200 BCE. It marked the start of the agricultural year with the New Year Akitu festival (from á-ki-ti-še-gur-ku, = sowing of the barley), an important date in Mespotamian religion.

The death of Gugalanna, represents the obscuring disappearance of this constellation as a result of the light of the sun, with whom Gilgamesh was identified.

In the time in which this myth was composed, the Akitu festival at the Spring Equinox, due to the Precession of the Equinoxes did not occur in Aries, but in Taurus. At this time of the year, Taurus would have disappeared as it was obscured by the sun.

Joseph Campbell wrote in The masks of God: Oriental mythology (1991): “Between the period of the earliest female figurines circa 4500 B.C. … a span of a thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilised by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth.

Moreover by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and the laws of sky and earth.”

MAIN GODS

Anu

In Sumerian mythology, Anu (also An; meaning “sky, heaven”) was a sky-god, the god of heaven, lord of constellations, king of gods, spirits and demons, and dwelt in the highest heavenly regions. It was believed that he had the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and that he had created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the royal tiara. His attendant and minister of state was the god Ilabrat, the attendant and minister of state of the chief sky god Anu.

Anu existed in Sumerian cosmogony as a dome that covered the flat earth; Outside of this dome was the primordial body of water known as Tiamat (not to be confused with the subterranean Abzu).

KI or Gi is the sign for “earth”. In Akkadian orthography, it functions as a determiner for toponyms and has the syllabic values gi, ge, qi, and qe. As an earth goddess in Sumerian mythology, Ki was the chief consort of An, the sky god. In some legends Ki and An were brother and sister, being the offspring of Anshar (“Sky Pivot”) and Kishar (“Earth Pivot”), earlier personifications of heaven and earth.

By her consort Anu, Ki gave birth to the Anunnaki, the most prominent of these deities being Enlil, god of the air. According to legends, heaven and earth were once inseparable until Enlil was born; Enlil cleaved heaven and earth in two. An carried away heaven. Ki, in company with Enlil, took the earth.

Some authorities question whether Ki was regarded as a deity since there is no evidence of a cult and the name appears only in a limited number of Sumerian creation texts. Samuel Noah Kramer identifies Ki with the Sumerian mother goddess Ninhursag and claims that they were originally the same figure. She later developed into the Akkadian goddess Antu (also known as “Keffen Anu”, “Kef”, and “Keffenk Anum”), consort of the god Anu (from Sumerian An).

In Sumerian, the designation “An” was used interchangeably with “the heavens” so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted. The Akkadians inherited An as the god of heavens from the Sumerian as Anu-, and in Akkadian cuneiform, the DINGIR character may refer either to Anum or to the Akkadian word for god, ilu-, and consequently had two phonetic values an and il. Hittite cuneiform as adapted from the Old Assyrian kept the an value but abandoned il.

The purely theoretical character of Anu is thus still further emphasized, and in the annals and votive inscriptions as well as in the incantations and hymns, he is rarely introduced as an active force to whom a personal appeal can be made. His name becomes little more than a synonym for the heavens in general and even his title as king or father of the gods has little of the personal element in it.

Anu was one of the oldest gods in the Sumerian pantheon and part of a triad including Enlil (god of the air) and Enki (god of water). He was called Anu by the later Akkadians in Babylonian culture. By virtue of being the first figure in a triad consisting of Anu, Enlil, and Enki (also known as Ea), Anu came to be regarded as the father and at first, king of the gods.

The doctrine once established remained an inherent part of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion and led to the more or less complete disassociation of the three gods constituting the triad from their original local limitations. An intermediate step between Anu viewed as the local deity of Uruk, Enlil as the god of Nippur, and Ea as the god of Eridu is represented by the prominence which each one of the centres associated with the three deities in question must have acquired, and which led to each one absorbing the qualities of other gods so as to give them a controlling position in an organized pantheon.

For Nippur we have the direct evidence that its chief deity, En-lil, was once regarded as the head of the Sumerian pantheon. The sanctity and, therefore, the importance of Eridu remained a fixed tradition in the minds of the people to the latest days, and analogy therefore justifies the conclusion that Anu was likewise worshipped in a centre which had acquired great prominence.

In the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively. The summing-up of divine powers manifested in the universe in a threefold division represents an outcome of speculation in the schools attached to the temples of Babylonia, but the selection of Anu, Enlil (and later Marduk), and Ea for the three representatives of the three spheres recognized, is due to the importance which, for one reason or the other, the centres in which Anu, Enlil, and Ea were worshipped had acquired in the popular mind.

Each of the three must have been regarded in his centre as the most important member in a larger or smaller group, so that their union in a triad marks also the combination of the three distinctive pantheons into a harmonious whole.

Antum

A consort Antum (or as some scholars prefer to read, Anatum) is assigned to him, on the theory that every deity must have a female associate, but Anu spent so much time on the ground protecting the Sumerians he left her in Heaven and then met Innin, whom he renamed Innan, or, “Queen of Heaven”. She was later known as Inanna/Ishtar. Anu resided in her temple the most, and rarely went back up to Heaven. He is also included in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and is a major character in the clay tablets.

In Akkadian mythology, Antu or Antum (add the name in cuneiform please an= shar=?) is a Babylonian goddess. She was the first consort of Anu, and the pair was the parents of the Anunnaki and the Utukki, a type of spirit or demon that could be either benevolent or evil.

In Akkadian mythology, the Utukku were seven evil demons who were the offspring of Anu and Antu. The evil utukku were called Edimmu or Ekimmu; the good utukku were called shedu. Two of the best known of the evil Utukku were Asag (slain by Ninurta) and Alû.

Anu is so prominently associated with the E-anna temple in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech) in southern Babylonia that there are good reasons for believing this place to be the original seat of the Anu cult. If this is correct, then the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar) of Uruk may at one time have been his consort.

Antu was replaced as consort by Inanna/Ishtar, who may also be a daughter of Anu and Antu. She is similar to Anat, a major northwest Semitic goddess. Antu was a dominant feature of the Babylonian akit festival until as recently as 200 BC, her later pre-eminence possibly attributable to identification with the Greek goddess Hera.

In Akkadian, the form one would expect Anat to take would be Antu, earlier Antum. This would also be the normal feminine form that would be taken by Anu, the Akkadian form of An ‘Sky’, the Sumerian god of heaven.

Antu appears in Akkadian texts mostly as a rather colorless consort of Anu, the mother of Ishtar in the Gilgamesh story, but is also identified with the northwest Semitic goddess ‘Anat of essentially the same name.

It is unknown whether this is an equation of two originally separate goddesses whose names happened to fall together or whether Anat’s cult spread to Mesopotamia, where she came to be worshipped as Anu’s spouse because the Mesopotamian form of her name suggested she was a counterpart to Anu.

It has also been suggested that the parallelism between the names of the Sumerian goddess, Inanna, and her West Semitic counterpart, Ishtar, continued in Canaanite tradition as Anath and Astarte, particularly in the poetry of Ugarit.

The two goddesses were invariably linked in Ugaritic scripture and are also known to have formed a triad (known from sculpture) with a third goddess who was given the name/title of Qadesh (meaning “the holy one”).

In the Ugaritic Ba‘al/Hadad cycle ‘Anat is a violent war-goddess, a virgin (btlt ‘nt) who is the sister and, according to a much disputed theory, the lover of the great god Ba‘al Hadad. Ba‘al is usually called the son of Dagan and sometimes the son of El, who addresses ‘Anat as “daughter”. Either relationship is probably figurative.

‘Anat’s titles used again and again are “virgin ‘Anat” and “sister-in-law of the peoples” (or “progenitress of the peoples” or “sister-in-law, widow of the Li’mites”).

In a fragmentary passage from Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra), Syria ‘Anat appears as a fierce, wild and furious warrior in a battle, wading knee-deep in blood, striking off heads, cutting off hands, binding the heads to her torso and the hands in her sash, driving out the old men and townsfolk with her arrows, her heart filled with joy. “Her character in this passage anticipates her subsequent warlike role against the enemies of Baal”.

’Anat boasts that she has put an end to Yam the darling of El, to the seven-headed serpent, to Arsh the darling of the gods, to Atik ‘Quarrelsome’ the calf of El, to Ishat ‘Fire’ the bitch of the gods, and to Zabib ‘flame?’ the daughter of El.

Later, when Ba‘al is believed to be dead, she seeks after Ba‘al “like a cow for its calf” and finds his body (or supposed body) and buries it with great sacrifices and weeping. ‘Anat then finds Mot, Ba‘al Hadad’s supposed slayer and she seizes Mot, splits him with a sword, winnows him with a sieve, burns him with fire, grinds him with millstones and scatters the remnants to the birds.

Anat first appears in Egypt in the 16th dynasty (the Hyksos period) along with other northwest Semitic deities. She was especially worshiped in her aspect of a war goddess, often paired with the goddess `Ashtart. In the Contest Between Horus and Set, these two goddesses appear as daughters of Re and are given in marriage to the god Set, who had been identified with the Semitic god Hadad.

Khumban

Khumban is the Elamite, an ancient Pre-Iranic civilization centered in the far west and southwest of what is now modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan (Luristan o Bakhtiari Lurs) and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq, god of the sky. His sumerian equivalent is Anu. Several Elamite kings, mostly from the Neo-Elamite period, were named in honour of Khumban.

The modern name Elam is a transcription from Biblical Hebrew, corresponding to the Sumerian elam(a), the Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was more often referred to as Susiana a name derived from its capital, Susa. However, Susiana is not synonymous with Elam and, in its early history, was a distinctly separate cultural and political entity.

Situated just to the east of Mesopotamia, Elam was part of the early urbanization during the Chalcolithic period (Copper Age). The emergence of written records from around 3000 BC also parallels Mesopotamian history, where slightly earlier records have been found.

In the Old Elamite period (Middle Bronze Age), Elam consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centered in Anshan, and from the mid-2nd millennium BC, it was centered in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role during the Persian Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded Elam, when the Elamite language remained among those in official use. Elamite is generally accepted to be a language isolate.

The Elamites called their country Haltamti, Sumerian ELAM, Akkadian Elamû, female Elamītu “resident of Susiana, Elamite”. Additionally, it is known as Elam in the Hebrew Bible, where they are called the offspring of Elam, eldest son of Shem (Genesis 10:22, Ezra 4:9).

The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, Susa. Geographers after Ptolemy called it Susiana. The Elamite civilization was primarily centered in the province of what is modern-day Khuzestān and Ilam in prehistoric times.

The modern provincial name Khuzestān is derived from the Persian name for Susa: Old Persian Hūjiya “Elam”, in Middle Persian Huź “Susiana”, which gave modern Persian Xuz, compounded with -stan “place” (cf. Sistan “Saka-land”).

Kumarbi

El was identified by the Hurrians with Sumerian Enlil, and by the Ugaritians with Kumarbi, the chief god of the Hurrians. He is the son of Anu (the sky), and father of the storm-god Teshub.

The Song of Kumarbi or Kingship in Heaven is the title given to a Hittite version of the Hurrian Kumarbi myth, dating to the 14th or 13th century BC. It is preserved in three tablets, but only a small fraction of the text is legible.

The song relates that Alalu, considered to have housed “the Hosts of Sky”, the divine family, because he was a progenitor of the gods, and possibly the father of Earth, was overthrown by Anu who was in turn overthrown by Kumarbi.

The word “Alalu” borrowed from Semitic mythology and is a compound word made up of the Semitic definite article “Al” and the Semitic supreme deity “Alu.” The “u” at the end of the word is a termination to denote a grammatical inflection. Thus, “Alalu” may also occur as “Alali” or “Alala” depending on the position of the word in the sentence. He was identified by the Greeks as Hypsistos. He was also called Alalus.

Alalu was a primeval deity of the Hurrian mythology. After nine years of reign, Alalu was defeated by his son Anu. Anuʻs son Kumarbi also defeated his father, and his son Teshub defeated him, too. Alalu fled to the underworld.

Scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian creation myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

When Anu tried to escape, Kumarbi bit off his genitals and spat out three new gods. In the text Anu tells his son that he is now pregnant with the Teshub, Tigris, and Tašmišu. Upon hearing this Kumarbi spit the semen upon the ground and it became impregnated with two children. Kumarbi is cut open to deliver Tešub. Together, Anu and Teshub depose Kumarbi.

In another version of the Kingship in Heaven, the three gods, Alalu, Anu, and Kumarbi, rule heaven, each serving the one who precedes him in the nine-year reign. It is Kumarbi’s son Tešub, the Weather-God, who begins to conspire to overthrow his father.

From the first publication of the Kingship in Heaven tablets scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian creation myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

SECOND LEVEL

Enlil

Enlil (nlin) (EN = Lord + LÍL = Wind, “Lord (of the) Storm”) is the God of breath, wind, loft and breadth (height and distance). It was the name of a chief deity listed and written about in Sumerian religion, and later in Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian), Hittite, Canaanite and other Mesopotamian clay and stone tablets.

The name is perhaps pronounced and sometimes rendered in translations as “Ellil” in later Akkadian, Hittite, and Canaanite literature. In later Akkadian, Enlil is the son of Anshar and Kishar. Enlil was known as the inventor of the mattock (a key agricultural pick, hoe, ax or digging tool of the Sumerians) and helped plants to grow.

The myth of Enlil and Ninlil discusses when Enlil was a young god, he was banished from Ekur in Nippur, home of the gods, to Kur, the underworld for seducing a goddess named Ninlil. Ninlil followed him to the underworld where she bore his first child, the moon god Sin (Sumerian Nanna/Suen). After fathering three more underworld-deities (substitutes for Sin), Enlil was allowed to return to the Ekur.

By his wife Ninlil or Sud, Enlil was father of the moon god Nanna/Suen (in Akkadian, Sin) and of Ninurta (also called Ningirsu). Enlil is the father of Nisaba the goddess of grain, of Pabilsag who is sometimes equated with Ninurta, and sometimes of Enbilulu. By Ereshkigal Enlil was father of Namtar.

In one myth, Enlil gives advice to his son, the god Ninurta, advising him on a strategy to slay the demon Asag. This advice is relayed to Ninurta by way of Sharur, his enchanted talking mace, which had been sent by Ninurta to the realm of the gods to seek counsel from Enlil directly.

Enlil is associated with the ancient city of Nippur, sometimes referred to as the cult city of Enlil. His temple was named Ekur, “House of the Mountain.” Such was the sanctity acquired by this edifice that Babylonian and Assyrian rulers, down to the latest days, vied with one another to embellish and restore Enlil’s seat of worship. Eventually, the name Ekur became the designation of a temple in general.

Grouped around the main sanctuary, there arose temples and chapels to the gods and goddesses who formed his court, so that Ekur became the name for an entire sacred precinct in the city of Nippur. The name “mountain house” suggests a lofty structure and was perhaps the designation originally of the staged tower at Nippur, built in imitation of a mountain, with the sacred shrine of the god on the top.

Enlil was also known as the god of weather. According to the Sumerians, Enlil helped create the humans, but then got tired of their noise and tried to kill them by sending a flood. A mortal known as Utnapishtim survived the flood through the help of another god, Ea, and he was made immortal by Enlil after Enlil’s initial fury had subsided.

As Enlil was the only god who could reach An, the god of heaven, he held sway over the other gods who were assigned tasks by his agent and would travel to Nippur to draw in his power. He is thus seen as the model for kingship. Enlil was assimilated to the north “Pole of the Ecliptic”. His sacred number name was 50.

At a very early period prior to 3000 BC, Nippur had become the centre of a political district of considerable extent. Inscriptions found at Nippur, where extensive excavations were carried on during 1888–1900 by John P. Peters and John Henry Haynes, under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, show that Enlil was the head of an extensive pantheon. Among the titles accorded to him are “king of lands”, “king of heaven and earth”, and “father of the gods”.

Anzû

Anzû (before misread as Zû), also known as Imdugud (meaning heavy rain, slingstone, ball of clay, thunderbird, hail storm), in Sumerian, (from An “heaven” and Zu “to know”, in the Sumerian language) is a lesser divinity or monster of Akkadian mythology, and the son of the bird goddess Siris, the patron of beer who is conceived of as a demon, which is not necessarily evil. Siris is considered the mother of Zu. Both Anzû and Siris are seen as massive birds who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately seen as a lion-headed eagle (like a reverse griffin).

Im-gíri means lightning storm (‘storm’ + ‘lightning flash’), im…mir means to be windy (‘wind’ + ‘storm wind’), im-ri-ha-mun means storm, whirlwind (‘weather’ + ‘to blow’ + ‘mutually opposing’), im…šèg means to rain (‘storm’ + ‘to rain’), and im-u-lu means southwind (‘wind’ + ‘storm’).

In Sumerian Tu, and damu, means weak, young or child. The Sumerian word /tur/ is also an allusion to the word for uterus/womb (šà-tùr). Some scholars follow the traditional interpretation that the element /tu/ is the same as the Sumerian verb /tudr/ “to give birth,” but this has been contested on phonological grounds.

Anzu was conceived by the pure waters of the Apsu and the wide Earth. He was a servant of the chief sky god Enlil, guard of the throne in Enlil’s sanctuary, (possibly previously a symbol of Anu), from whom Anzu stole the Tablet of Destinies, so hoping to determine the fate of all things. In one version of the legend the gods sent Lugalbanda to retrieve the tablets, who kills Anzu.

In another, Ea and Belet-Ili conceived Ninurta for the purpose of retrieving the tablets. In a third legend, found in The Hymn of Ashurbanipal, Marduk is said to have killed Anzu.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzû is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds. This demon—half man and half bird—stole the “Tablets of Destiny” from Enlil and hid them on a mountaintop.

Anu ordered the other gods to retrieve the tablets, even though they all feared the demon. According to one text, Marduk killed the bird; in another, it died through the arrows of the god Ninurta. The bird is also referred to as Imdugud.

In Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with cosmogony, the theory concerning the coming into existence (or origin) of either the cosmos (or universe), or the so-called reality of sentient beings.

Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of umsimi (which is usually translated “crown” but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the “ideal creative organ.”) “Ham is the Chaldean Anzu, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime,” which parallels the mutilation of Uranos by Kronos and of Set by Horus.

Haya/Nidaba

Haya’s functions are two-fold: he appears to have served as a door-keeper but was also associated with the scribal arts, and may have had an association with grain. In the god-list AN = dA-nu-um preserved on manuscripts of the first millennium he is mentioned together with dlugal-[ki-sá-a], a divinity associated with door-keepers. Already in the Ur III period Haya had received offerings together with offerings to the “gate”. This was presumably because of the location of one of his shrines.

At least from the Old Babylonian period on he is known as the spouse of the grain-goddess Nidaba/Nissaba (Ops), the Sumerian goddess of grain and writing, patron deity of the city Ereš (Uruk), who is also the patroness of the scribal art.

The intricate connection between agriculture and accounting/writing implied that it was not long before Nidaba became the goddess of writing. From then on her main role was to be the patron of scribes. She was eventually replaced in that function by the god Nabu.

In a debate between Nidaba and Grain, Nidaba is syncretised with Ereškigal (Lua), whose name translates as “Lady of the Great Earth”, “Mistress of the Underworld”. Unlike her consort Nergal, Ereškigal has a distinctly dual association with death. This is reminiscent of the contradictive nature of her sister Inanna/Ištar, who simultaneously represents opposing aspects such as male and female; love and war. In Ereškigal’s case, she is the goddess of death but also associated with birth; regarded both as mother(-earth) and a virgin.

Ereškigal is the sister of Ištar and mother of the goddess Nungal. Namtar, Ereškigal’s minister, is also her son by Enlil; and Ninazu, her son by Gugal-ana. The latter is the first husband of Ereškigal, who in later tradition has Nergal as consort. Bēlet-ṣēri appears as the official scribe for Ereškigal in the Epic of Gilgameš.

With few exceptions Ereškigal had no cult in Mesopotamia and as a result, rarely encountered outside literature. Inscriptions, however, attest to temples of Ereškigal in Kutha, Assur and Umma.

Nidaba is also identified with the goddess of grain Ašnan, and with Nanibgal/Nidaba-ursag/Geme-Dukuga, the throne bearer of Ninlil and wife of Ennugi, throne bearer of Enlil. The Sumerian tale of the Curse of Agade lists Nidaba as belonging to the elite of the great gods.

Nidaba’s spouse is Haya and together they have a daughter, Sud/Ninlil. Traditions vary regarding the genealogy of Nidaba. She appears on separate occasions as the daughter of Enlil, of Uraš, of Ea, and of Anu. Two myths describe the marriage of Sud/Ninlil with Enlil. This implies that Nidaba could be at once the daughter and the mother-in-law of Enlil.

Nidaba is also the sister of Ninsumun, the mother of Gilgameš. Nidaba is frequently mentioned together with the goddess Nanibgal who also appears as an epithet of Nidaba, although most god lists treat her as a distinct goddess.

From the same period we have a Sumerian hymn composed in his honour, which celebrates him in these capacities. The hymn is preserved exclusively at Ur, leading Charpin to suggest that it was composed to celebrate a visit by king Rim-Sin of Larsa (r. 1822-1763 BCE) to his cella in the Ekišnugal, Nanna’s main temple at Ur.

While there is plenty of evidence to connect Haya with scribes, the evidence connecting him with grain is mainly restricted to etymological considerations, which are unreliable and suspect. There is also a divine name Haia(-)amma in a bilingual Hattic-Hittite text from Anatolia which is used as an equivalent for the Hattic grain-goddess Kait in an invocation to the Hittite grain-god Halki, although it is unclear whether this appellation can be related to dha-ià.

Haya is also characterised, beyond being the spouse of Nidaba/Nissaba, as an “agrig”-official of the god Enlil. The god-list AN = Anu ša amēli (lines 97-98) designates him as “the Nissaba of wealth”, as opposed to his wife, who is the “Nissaba of Wisdom”.

Attempts have also been made to connect the remote origins of dha-ià with those of the god Ea (Ebla Ḥayya), although there remain serious doubts concerning this hypothesis. How or whether both are related to a further western deity called Ḥayya is also unclear.

Khaldi

Ḫaldi (Ḫaldi, also known as Khaldi or Hayk) was one of the three chief deities of Ararat (Urartu). His shrine was at Ardini. The other two chief deities were Theispas of Kumenu, and Shivini of Tushpa. He seem to be the same as the god Haya/Janus.

Of all the gods of Ararat (Urartu) pantheon, the most inscriptions are dedicated to him. His wife was the goddess Arubani. He is portrayed as a man with or without a beard, standing on a lion.

Khaldi was a warrior god whom the kings of Urartu would pray to for victories in battle. The temples dedicated to Khaldi were adorned with weapons, such as swords, spears, bow and arrows, and shields hung off the walls and were sometimes known as ‘the house of weapons’.

Armenians

Beliefs of the ancient Armenians were associated with the worship of many cults, mainly the cult of ancestors, the worship of heavenly bodies (the cult of the Sun, the Moon cult, the cult of Heaven) and the worship of certain creatures (lions, eagles, bulls).

The main cult, however, was the worship of gods of the Armenian pantheon. The supreme god was the common Indo-European god Ar (as the starting point) followed by Vanatur. Later, due to the influence of Armenian-Persian relations, God the Creator was identified as Aramazd, and during the era of Hellenistic influence, he was identified with Zeus.

Hayk is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation. In Moses of Chorene’s account, after the arrogant Titanid Bel asserts himself as king, Hayk left Babylon to emigrate with his extended household of at least 300 to settle in the Ararat region, founding a village he names Haykashen.

The figure slain by Hayk’s arrow is variously given as Bel or Nimrod. Hayk is also the name of the Orion constellation in the Armenian translation of the Bible. Hayk’s flight from Babylon and his eventual defeat of Bel, was historically compared to Zeus’s escape to the Caucasus and eventual defeat of the titans.

Theispas (also known as Teisheba or Teišeba) of Kumenu was the Araratian (Urartian) weather-god, notably the god of storms and thunder. He was also sometimes the god of war. He formed part of a triad along with Khaldi and Shivini.

He is a counterpart to the Assyrian god Adad, and the Hurrian god, Teshub. He was often depicted as a man standing on a bull, holding a handful of thunderbolts. His wife was the goddess Huba, who was the counterpart of the Hurrian goddess Hebat.

Tir or Tiur is the Armenian god of wisdom, culture, science and studies. He also was an interpreter of dreams. He was the messenger of the gods and was associated with Apollo. Tir’s temple was located near Artashat.

Enki

Capricorn is the tenth astrological sign in the zodiac, originating from the constellation of Capricornus. It spans the 270–300th degree of the zodiac, corresponding to celestial longitude. Capricorn is ruled by the planet Saturn. In astrology, Capricorn is considered an earth sign, introvert sign, and one of the four cardinal signs.

Under the tropical zodiac, the sun transits this area from December 22 to January 19 each year, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun currently transits the constellation of Capricorn from approximately January 15 to February 14.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology Hanbi or Hanpa (more commonly known in western text) was the father of Enki, Pazuzu, the king of the demons of the wind, the bearer of storms and drought, and Humbaba, also Humbaba the Terrible, a monstrous giant of immemorial age raised by Utu, the Sun.

Although Pazuzu is, himself, an evil spirit, he drives away other evil spirits, therefore protecting humans against plagues and misfortunes. Humbaba was the guardian of the Cedar Forest, where the gods lived, by the will of the god Enlil.

The Encyclopedia Britannica states that the figure of Capricorn derives from the half-goat, half-fish representation of the Sumerian god Enki (Sumerian: EN.KI(G)), later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

Enki was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation. Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

Isimud (also Isinu; Usmû; Usumu (Akkadian) is a minor god, the messenger of the god Enki in Sumerian mythology. He is readily identifiable by the fact that he possesses two faces looking in opposite directions.

The main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu. He was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization.

His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, sometimes confused with the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water’”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He was accompanied by an attendant Isimud, who is readily identifiable by the fact that he possesses two faces looking in opposite directions.

He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki.

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael), with Ia.

Jean Bottero (1952) and others suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea, Enki’s Akkadian name, associating the Canaanite theonym Yahu, and ultimately Hebrew YHWH.

This hypothesis is dismissed by some scholars as erroneous, based on a mistaken cuneiform reading, but academic debate continues. Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic Yamm (sea), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw, or Ya’a.

Dagon

Dagon was originally an East Semitic Mesopotamian (Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian) fertility god who evolved into a major Northwest Semitic god, reportedly of grain (as symbol of fertility) and fish and/or fishing (as symbol of multiplying).

He was worshipped by the early Amorites and by the inhabitants of the cities of Ebla (modern Tell Mardikh, Syria) and Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria). He was also a major member, or perhaps head, of the pantheon of the Philistines.

His name is perhaps related to the Middle Hebrew and Jewish Aramaic word dgnʾ ‘be cut open’ or to Arabic dagn (دجن) ‘rain-(cloud)’. In Ugaritic, the root dgn also means grain: in Hebrew dāgān, Samaritan dīgan, is an archaic word for grain. The Phoenician author Sanchuniathon also says Dagon means siton, that being the Greek word for grain.

Sanchuniathon further explains: “And Dagon, after he discovered grain and the plough, was called Zeus Arotrios.” The word arotrios means “ploughman”, “pertaining to agriculture” (confer ἄροτρον “plow”).

The theory relating the name to Hebrew dāg/dâg, ‘fish’, is based solely upon a reading of 1 Samuel 5:2–7. According to this etymology: Middle English Dagon < Late Latin (Ec.) Dagon < Late Greek (Ec.) Δάγων < Heb דגן dāgān, “grain (hence the god of agriculture), corn.”

The god Dagon first appears in extant records about 2500 BC in the Mari texts and in personal Amorite names in which the Mesopotamian gods Ilu (Ēl), Dagan, and Adad are especially common.

At Ebla (Tell Mardikh), from at least 2300 BC, Dagan was the head of the city pantheon comprising some 200 deities and bore the titles BE-DINGIR-DINGIR, “Lord of the gods” and Bekalam, “Lord of the land”.

His consort was known only as Belatu, “Lady”. Both were worshipped in a large temple complex called E-Mul, “House of the Star”. One entire quarter of Ebla and one of its gates were named after Dagan. Dagan is called ti-lu ma-tim, “dew of the land” and Be-ka-na-na, possibly “Lord of Canaan”. He was called lord of many cities: of Tuttul, Irim, Ma-Ne, Zarad, Uguash, Siwad, and Sipishu.

An interesting early reference to Dagan occurs in a letter to King Zimri-Lim of Mari, 18th century BC, written by Itur-Asduu an official in the court of Mari and governor of Nahur (the Biblical city of Nahor) (ANET, p. 623).

It relates a dream of a “man from Shaka” in which Dagan appeared. In the dream, Dagan blamed Zimri-Lim’s failure to subdue the King of the Yaminites upon Zimri-Lim’s failure to bring a report of his deeds to Dagan in Terqa. Dagan promises that when Zimri-Lim has done so: “I will have the kings of the Yaminites [coo]ked on a fisherman’s spit, and I will lay them before you.”

In Ugarit around 1300 BC, Dagon had a large temple and was listed third in the pantheon following a father-god and Ēl, and preceding Baīl Ṣapān (that is the god Haddu or Hadad/Adad).

Joseph Fontenrose first demonstrated that, whatever their deep origins, at Ugarit Dagon was identified with El, explaining why Dagan, who had an important temple at Ugarit is so neglected in the Ras Shamra mythological texts, where Dagon is mentioned solely in passing as the father of the god Hadad, but Anat, El’s daughter, is Baal’s sister, and why no temple of El has appeared at Ugarit.

There are differences between the Ugaritic pantheon and that of Phoenicia centuries later: according to the third-hand Greek and Christian reports of Sanchuniathon, the Phoenician mythographer would have Dagon the brother of Ēl/Cronus and like him son of Sky/Uranus and Earth, but not truly Hadad’s father.

Hadad was begotten by “Sky” on a concubine before Sky was castrated by his son Ēl, whereupon the pregnant concubine was given to Dagon. Accordingly, Dagon in this version is Hadad’s half-brother and stepfather. The Byzantine Etymologicon Magnum says that Dagon was Cronus in Phoenicia. Otherwise, with the disappearance of Phoenician literary texts, Dagon has practically no surviving mythology.

Dagan is mentioned occasionally in early Sumerian texts, but becomes prominent only in later Assyro-Babylonian inscriptions as a powerful and warlike protector, sometimes equated with Enlil.

Dagan’s wife was in some sources the goddess Shala (also named as wife of Adad and sometimes identified with Ninlil). In other texts, his wife is Ishara. In the preface to his famous law code, King Hammurabi, the founder of the Babylonian empire, calls himself “the subduer of the settlements along the Euphrates with the help of Dagan, his creator”.

An inscription about an expedition of Naram-Sin to the Cedar Mountain relates (ANET, p. 268): “Naram-Sin slew Arman and Ibla with the ‘weapon’ of the god Dagan who aggrandizes his kingdom.”

The stele of the 9th century BC Assyrian emperor Ashurnasirpal II (ANET, p. 558) refers to Ashurnasirpal as the favorite of Anu and of Dagan. In an Assyrian poem, Dagan appears beside Nergal and Misharu as a judge of the dead. A late Babylonian text makes him the underworld prison warder of the seven children of the god Emmesharra.

The Phoenician inscription on the sarcophagus of King Eshmunʿazar of Sidon (5th century BC) relates (ANET, p. 662): “Furthermore, the Lord of Kings gave us Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of Dagon, which are in the Plain of Sharon, in accordance with the important deeds which I did.”

Fish god tradition

In the 11th century, Jewish bible commentator Rashi writes of a Biblical tradition that the name Dāgôn is related to Hebrew dāg/dâg ‘fish’ and that Dagon was imagined in the shape of a fish: compare the Babylonian fish-god Oannes.

In the 13th century David Kimhi interpreted the odd sentence in 1 Samuel 5.2–7 that “only Dagon was left to him” to mean “only the form of a fish was left”, adding: “It is said that Dagon, from his navel down, had the form of a fish (whence his name, Dagon), and from his navel up, the form of a man, as it is said, his two hands were cut off.” The Septuagint text of 1 Samuel 5.2–7 says that both the hands and the head of the image of Dagon were broken off.

Schmökel asserted in 1928 that Dagon was never originally a fish-god, but once he became an important god of those maritime Canaanites, the Phoenicians, the folk-etymological connection with dâg would have ineluctably affected his iconography.

The fish form may be considered as a phallic symbol as seen in the story of the Egyptian grain god Osiris, whose penis was eaten by (conflated with) fish in the Nile after he was attacked by the Typhonic beast Set.

Likewise, in the tale depicting the origin of the constellation Capricornus, the Greek god of nature Pan became a fish from the waist down when he jumped into the same river after being attacked by Typhon. Enki’s symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus.

Various 19th century scholars, such as Julius Wellhausen and William Robertson Smith, believed the tradition to have been validated from the occasional occurrence of a merman motif found in Assyrian and Phoenician art, including coins from Ashdod and Arvad.

El

Ēl (cognate to Akkadian: ilu) is a Northwest Semitic word meaning “deity”. Cognate forms are found throughout the Semitic languages. They include Ugaritic ʾil, pl. ʾlm; Phoenician ʾl pl. ʾlm; Hebrew ʾēl, pl. ʾēlîm; Aramaic ʾl; Akkadian ilu, pl. ilānu.

Elohim and Eloah ultimately derive from the root El, ‘strong’, possibly genericized from El (deity), as in the Ugaritic ’lhm (consonants only), meaning “children of El” (the ancient Near Eastern creator god in pre-Abrahamic tradition).

In the Canaanite religion, or Levantine religion as a whole, El or Il was a god also known as the Father of humanity and all creatures, and the husband of the goddess Asherah as recorded in the clay tablets of Ugarit (modern Ra′s Shamrā, Syria).

In northwest Semitic use, El was both a generic word for any god and the special name or title of a particular god who was distinguished from other gods as being “the god”. El is listed at the head of many pantheons. El is the Father God among the Canaanites.

However, because the word sometimes refers to a god other than the great god Ēl, it is frequently ambiguous as to whether Ēl followed by another name means the great god Ēl with a particular epithet applied or refers to another god entirely. For example, in the Ugaritic texts, ʾil mlk is understood to mean “Ēl the King” but ʾil hd as “the god Hadad”.

The bull was symbolic to El and his son Baʻal Hadad, and they both wore bull horns on their headdress. He may have been a desert god at some point, as the myths say that he had two wives and built a sanctuary with them and his new children in the desert. El had fathered many gods, but most important were Hadad, Yam, and Mot.

Cronus

The Romans identified Saturn with the Greek Cronus, whose myths were adapted for Latin literature and Roman art. In particular, Cronus’s role in the genealogy of the Greek gods was transferred to Saturn. As early as Livius Andronicus (3rd century BC), Jupiter (Zeus) was called the son of Saturn. Cronus was also identified in classical antiquity with the Roman deity Saturn.

Cronus, or both Cronos and Kronos, was in Greek mythology the leader and the youngest of the first generation of Titans, the divine descendants of Uranus, the sky and Gaia, the earth. He overthrew his father and ruled during the mythological Golden Age, until he was overthrown by his own son Zeus and imprisoned in Tartarus.

Cronus was usually depicted with a Harpe, Scythe or a Sickle, which was the instrument he used to castrate and depose Uranus, his father. In Athens, on the twelfth day of the Attic month of Hekatombaion, a festival called Kronia was held in honour of Cronus to celebrate the harvest, suggesting that, as a result of his association with the virtuous Golden Age, Cronus continued to preside as a patron of harvest.

A theory debated in the 19th century, and sometimes still offered somewhat apologetically, holds that Kronos is related to “horned”, assuming a Semitic derivation from qrn. Andrew Lang’s objection, that Cronus was never represented horned in Hellenic art, was addressed by Robert Brown, arguing that in Semitic usage, as in the Hebrew Bible qeren was a signifier of “power”. When Greek writers encountered the Levantine deity El, they rendered his name as Kronos.

Robert Graves proposed that cronos meant “crow”, related to the Ancient Greek word corōnē (κορώνη) “crow”, noting that Cronus was depicted with a crow, as were the deities Apollo, Asclepius, Saturn and Bran.

The beginning of time

When Hellenes encountered Phoenicians and, later, Hebrews, they identified the Semitic El, by interpretatio graeca, with Cronus. The association was recorded c. AD 100 by Philo of Byblos’ Phoenician history, as reported in Eusebius’ Præparatio Evangelica I.10.16.

Philo’s account, ascribed by Eusebius to the semi-legendary pre-Trojan War Phoenician historian Sanchuniathon, indicates that Cronus was originally a Canaanite ruler who founded Byblos and was subsequently deified.

This version gives his alternate name as Elus or Ilus, and states that in the 32nd year of his reign, he emasculated, slew and deified his father Epigeius or Autochthon “whom they afterwards called Uranus”. It further states that after ships were invented, Cronus, visiting the ‘inhabitable world’, bequeathed Attica to his own daughter Athena and Egypt to Taautus the son of Misor and inventor of writing.

While the Greeks considered Cronus a cruel and tempestuous force of chaos and disorder, believing the Olympian gods had brought an era of peace and order by seizing power from the crude and malicious Titans, the Romans took a more positive and innocuous view of the deity, by conflating their indigenous deity Saturn with Cronus.

Consequently, while the Greeks considered Cronus merely an intermediary stage between Uranus and Zeus, he was a larger aspect of Roman religion. The Saturnalia was a festival dedicated in his honour, and at least one temple to Saturn already existed in the archaic Roman Kingdom.

His association with the “Saturnian” Golden Age eventually caused him to become the god of “time”, i.e., calendars, seasons, and harvests—not now confused with Chronos, the unrelated embodiment of time in general; nevertheless, among Hellenistic scholars in Alexandria and during the Renaissance, Cronus was conflated with the name of Chronos, the personification of “Father Time”, wielding the harvesting scythe.

As a result of Cronus’ importance to the Romans, his Roman variant, Saturn, has had a large influence on Western culture. The seventh day of the Judaeo-Christian week is called in Latin Dies Saturni (“Day of Saturn”), which in turn was adapted and became the source of the English word Saturday. In astronomy, the planet Saturn is named after the Roman deity. It is the outermost of the Classical planets (those that are visible with the naked eye).

The myth of Cronus castrating Uranus parallels the Song of Kumarbi, where Anu (the heavens) is castrated by Kumarbi. In the Song of Ullikummi, Teshub uses the “sickle with which heaven and earth had once been separated” to defeat the monster Ullikummi, establishing that the “castration” of the heavens by means of a sickle was part of a creation myth, in origin a cut creating an opening or gap between heaven (imagined as a dome of stone) and earth enabling the beginning of time (Chronos) and human history.

Recently, Janda (2010) offers a genuinely Indo-European etymology of “the cutter”, from the root *(s)ker- “to cut” (Greek keirō), c.f. English shear), motivated by Cronus’ characteristic act of “cutting the sky” (or the genitals of anthropomorphic Uranus).

The Indo-Iranian reflex of the root is kar, generally meaning “to make, create” (whence karma), but Janda argues that the original meaning “to cut” in a cosmogonic sense is still preserved in some verses of the Rigveda pertaining to Indra’s heroic “cutting”, like that of Cronus resulting in creation:

In RV 10.104.10: ārdayad vṛtram akṛṇod ulokaṃ – “he hit Vrtra fatally, cutting [> creating] a free path” and in RV 6.47.4: varṣmāṇaṃ divo akṛṇod – “he cut [> created] the loftiness of the sky.”

This may point to an older Indo-European mytheme reconstructed as *(s)kert wersmn diwos “by means of a cut he created the loftiness of the sky”.

During antiquity, Cronus was occasionally interpreted as Chronos, the personification of time; according to Plutarch the Greeks believed that Cronus was an allegorical name for Chronos.

In addition to the name, the story of Cronus eating his children was also interpreted as an allegory to a specific aspect of time held within Cronus’ sphere of influence. As the theory went, Cronus represented the destructive ravages of time which consumed all things, a concept that was definitely illustrated when the Titan king devoured the Olympian gods — the past consuming the future, the older generation suppressing the next generation. During the Renaissance, the identification of Cronus and Chronos gave rise to “Father Time” wielding the harvesting scythe.

Saturn

Saturn the planet is named after the god Saturn (Latin: Saturnus), a god in ancient Roman religion, and a character in myth. Saturn is a complex figure because of his multiple associations and long history.

According to Varro, Saturn’s name was derived from satu, “sowing.” Even though this etymology looks implausible on linguistic grounds (for the long quantity of the a in Sāturnus and also because of the epigraphically attested form Saeturnus) nevertheless it does reflect an original feature of the god.

A more probable etymology connects the name with Etruscan god Satre and placenames such as Satria, an ancient town of Latium, and Saturae palus, a marsh also in Latium. This root may be related to Latin phytonym satureia.

Another epithet of his that referred to his agricultural functions was Sterculius or Stercutus, Sterces from stercus, “manure.” Agriculture was important to Roman identity, and Saturn was a part of archaic Roman religion and ethnic identity. His name appears in the ancient hymn of the Salian priests, and his temple was the oldest known to have been recorded by the pontiffs.

The exact meaning of Enki’s name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

He was the first god of the Capitol, known since the most ancient times as Saturnius Mons, and was seen as a god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation. Under Saturn’s rule, humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor in the “Golden Age” described by Hesiod and Ovid.

In later developments he came to be also a god of time. His reign was depicted as a Golden Age of plenty and peace. Macrobius states explicitly that the Roman legend of Janus and Saturn is an affabulation, as the true meaning of religious beliefs cannot be openly expressed.

In the myth Saturn was the original and autochthonous ruler of the Capitolium, which had thus been called the Mons Saturnius in older times and on which once stood the town of Saturnia. He was sometimes regarded as the first king of Latium or even the whole of Italy.

At the same time, there was a tradition that Saturn had been an immigrant god, received by Janus after he was usurped by his son Jupiter and expelled from Greece. In Versnel’s view his contradictions – a foreigner with one of Rome’s oldest sanctuaries, and a god of liberation who is kept in fetters most of the year – indicate Saturn’s capacity for obliterating social distinctions.

The Golden Age of Saturn’s reign in Roman mythology differed from the Greek tradition. He arrived in Italy “dethroned and fugitive,” but brought agriculture and civilization for which things was rewarded by Janus with a share of the kingdom, becoming he himself king.

Saturn is associated with a major religious festival in the Roman calendar, Saturnalia. Saturnalia celebrated the harvest and sowing, and ran from December 17–23. Macrobius (5th century AD) presents an interpretation of the Saturnalia as a festival of light leading to the winter solstice.

The renewal of light and the coming of the New Year is celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis of Sol Invictus, the “Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun,” on December 25.

The Winter solstice was thought to occur on December 25. January 1 was New Year day: the day was consecrated to Janus since it was the first of the New Year and of the month (kalends) of Janus: the feria had an augural character as Romans believed the beginning of anything was an omen for the whole.

Thus on that day it was customary to exchange cheerful words of good wishes. For the same reason everybody devoted a short time to his usual business, exchanged dates, figs and honey as a token of well wishing and made gifts of coins called strenae. Cakes made of spelt (far) and salt were offered to the god and burnt on the altar.

Ovid states that in most ancient times there were no animal sacrifices and gods were propitiated with offerings of spelt and pure salt. This libum was named ianual and it was probably correspondent to the summanal offered the day before the Summer solstice to god Summanus, which however was sweet being made with flour, honey and milk. Shortly afterwards, on January 9, on the feria of the Agonium of January the rex sacrorum offered the sacrifice of a ram to Janus.

Saturn had two consorts who represented different aspects of the god. The name of his wife Ops, the Roman equivalent of Greek Rhea, means “wealth, abundance, resources.” The association with Ops though is considered a later development, as this goddess was originally paired with Consus. Earlier was Saturn’s association with Lua (“destruction, dissolution, loosening”), a goddess who received the bloodied weapons of enemies destroyed in war.

Janus

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus (Latin: Ianus) is the god of beginnings and transitions, and thereby of gates, doors, doorways, passages and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces, since he looks to the future and to the past. The Romans named the month of January (Ianuarius) in his honor.

Janus presided over the beginning and ending of conflict, and hence war and peace. The doors of his temple were open in time of war, and closed to mark the peace. As a god of transitions, he had functions pertaining to birth and to journeys and exchange, and in his association with Portunus, a similar harbor and gateway god, he was concerned with travelling, trading and shipping.

Janus had no flamen or specialized priest (sacerdos) assigned to him, but the King of the Sacred Rites (rex sacrorum) himself carried out his ceremonies. Janus had a ubiquitous presence in religious ceremonies throughout the year, and was ritually invoked at the beginning of each one, regardless of the main deity honored on any particular occasion.

The interpretation of Janus as the god of beginnings and transitions is based on a third etymology indicated by Cicero, Ovid and Macrobius, which explains the name as Latin, deriving it from the verb ire (“to go”). From Ianus derived ianua (“door”), and hence the English word “janitor” (Latin, ianitor).

Janus and Juno

The relationship between Janus and Juno, the protector and special counselor of the state, is defined by the closeness of the notions of beginning and transition and the functions of conception and delivery, result of youth and vital force. Ancient etymologies associated Juno’s name with iuvare, “to aid, benefit”, and iuvenescendo, “rejuvenate”.

Juno is a daughter of Saturn and sister (but also the wife) of the chief god Jupiter and the mother of Mars and Vulcan. Juno also looked after the women of Rome. Her Greek equivalent was Hera, the wife and one of three sisters of Zeus, the goddess of women and marriage. Hera’s mother is Rhea and her father Cronus.

The cow, lion and the peacock were considered sacred to her. In Greco-Roman mythology the Peacock is identified with Hera (Juno) who created the Peacock from Argus whose hundred eyes (seen on the tail feathers of the Peacock) symbolize the vault of heaven and the “eyes” of the stars.

Juno’s own warlike aspect among the Romans is apparent in her attire. She often appeared sitting pictured with a peacock armed and wearing a goatskin cloak. The traditional depiction of this warlike aspect was assimilated from the Greek goddess Hera, whose goatskin was called the ‘aegis’.

Her Etruscan counterpart was Uni, the supreme goddess of the Etruscan pantheon and the patron goddess of Perugia. In the Etruscan tradition, it is Uni who grants access to immortality to the demigod Hercle (Greek Heracles, Latin Hercules) by offering her breast milk to him.

Uni appears in the Etruscan text on the Pyrgi Tablets as the translation of the Phoenician goddess Astarte. Livy states (Book V, Ab Urbe Condita) that Juno was an Etruscan goddess of the Veientes, who was ceremonially adopted into the Roman pantheon when Veii was sacked in 396BC. This seems to refer to Uni. She also appears on the Liver of Piacenza.

As the patron goddess of Rome and the Roman Empire, Juno was called Regina (“Queen”) and, together with Jupiter and Minerva, was worshipped as a triad on the Capitol (Juno Capitolina) in Rome.

Janus/Portunes

Portunes (alternatively spelled Portumnes or Portunus) may be defined as a sort of duplication inside the scope of the powers and attributes of Janus. His original definition shows he was the god of gates and doors and of harbours, a god of keys, doors and livestock. He protected the warehouses where grain was stored. Probably because of folk associations between porta “gate, door” and portus “harbor”, the “gateway” to the sea, Portunus later became conflated with Palaemon and evolved into a god primarily of ports and harbors.

In the Latin adjective importunus his name was applied to untimely waves and weather and contrary winds, and the Latin echoes in English opportune and its old-fashioned antonym importune, meaning “well timed’ and “badly timed”. Hence Portunus is behind both an opportunity and importunate or badly timed solicitations.

Portunus appears to be closely related to the god Janus, with whom he shares many characters, functions and the symbol of the key. He too was represented as a two headed being, with each head facing opposite directions, on coins and as figurehead of ships. He was considered to be “deus portuum portarumque praeses” (lit. God presiding over ports and gates.)

The relationship between the two gods is underlined by the fact that the date chosen for the dedication of the rebuilt temple of Janus in the Forum Holitorium by emperor Tiberius is the day of the Portunalia, August 17.