The colonization of Europe

The Gravettian toolmaking culture was a specific archaeological industry of the European Upper Palaeolithic era prevalent before the last glacial epoch. It is named after the type site of La Gravette in the Dordogne region of France where its characteristic tools were first found and studied.

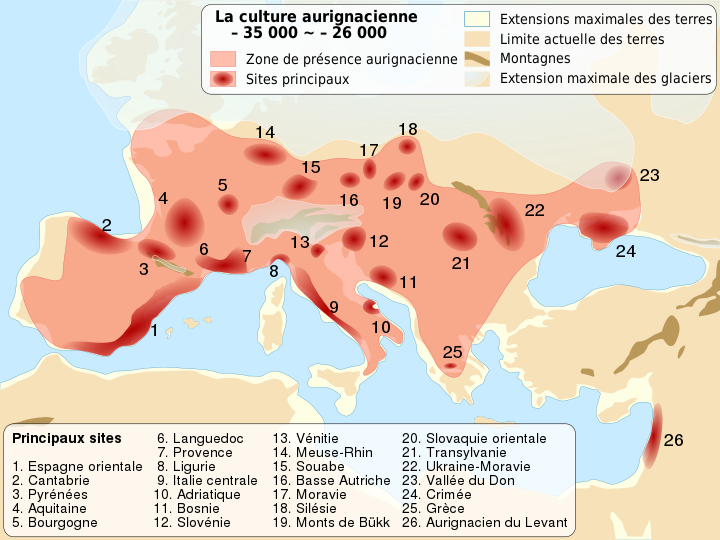

The earliest signs of the culture were found at Kozarnika, Bulgaria. One of the earliest artifacts is also found in eastern Crimea (Buran-Kaya) dated 32 000 years ago. It lasted until 22,000 years ago. Where found, it succeeded the artifacts datable to the Aurignacian culture.

In August 2013, the Romanian archaeologists have found a 20,000 years old Gravettian pendant at the paleolithic site of Poiana Ciresului (English: Cherry Glade), near Piatra Neamț, in eastern Romania.

The newly discovered objects will be included in the Paleolithic artifacts collection of Târgoviște History Museum, in the new section of human evolution. The department will open at “Stelea” Galleries with the support of Dâmboviţa County Council.

The diagnostic characteristic artifacts of the industry are small pointed restruck blade with a blunt but straight back, a carving tool known as a Noailles burin. (See to compare with similar purposed modern tool: burin)

Artistic achievements of the Gravettian cultural stage include the hundreds of Venus figurines, which are widely distributed in Europe. The predecessor culture was linked to similar figurines and carvings.

People in the Gravettian period is characterized by a stone-tool industry with small pointed blades used for big-game hunting (bison, horse, reindeer and mammoth). It also used nets to hunt small game. For more information on hunting see Animal Usage in the Gravettian.

It is divided into two regional groups: the western Gravettian, mostly known from cave sites in France, and the eastern Gravettian, with open sites of specialized mammoth hunters on the plains of central Europe and Russia such as the derivative Pavlovian culture.

Artifacts and technologies of this and the preceding Aurignacian culture figure centrally in the romanticized adaptation of the culture in the popular fictional pre-history depicted in the Earth’s Children novel series which leans heavily on archeological finds and theories from this era. In the series, the Venus figurines are central to a fertility rite and worship of “The Great Earth Mother”, a nature spirit from which all life flows.

Périgordian is a term for several distinct but related Upper Upper Palaeolithic cultures which are thought by some archaeologists to represent a contiguous tradition. It existed between c.35,000 BP and c.20,000 BP.

The earliest culture in the tradition is known as the Châtelperronian which produced denticulate tools and distinctive flint knives. It is argued that this was superseded by the Gravettian with its Font Robert points and Noailles burins. The tradition culminated in the proto-Magdalenian.

Critics have pointed out that no continuous sequence of Périgordian occupation has yet been found and that the tradition requires it to have co-existed separately from the Aurignacian industry rather than being differing industries that existed before and afterwards.

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) refers to a period in the Earth’s climate history when ice sheets were at their maximum extension, between 26,500 and 19,000–20,000 years ago, marking the peak of the last glacial period. During this time, vast ice sheets covered much of North America, northern Europe and Asia. These ice sheets profoundly impacted Earth’s climate, causing drought, desertification, and a dramatic drop in sea levels. It was followed by the Late Glacial Maximum.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, much of the world was cold, dry, and inhospitable, with frequent storms and a dust-laden atmosphere. The dustiness of the LGM atmosphere is a prominent feature in ice cores; dust levels were as much as 20 to 25 times greater than at present.

This was probably due to a number of factors: reduced vegetation, stronger global winds, and less precipitation to clear dust from the atmosphere. The massive sheets of ice locked away water, lowering the sea level, exposing continental shelves, joining land masses together, and creating extensive coastal plains.

Northern Europe was largely covered by ice, the southern boundary of the ice sheets passing through Germany and Poland. This ice extended northward to cover Svalbard and Franz Josef Land and northeastward to occupy the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea and Novaya Zemlya, ending at the Taymyr Peninsula.

Permafrost covered Europe south of the ice sheet down to present-day Szeged in Southern Hungary. Ice covered the whole of Iceland and almost all of the British Isles but southern England. Britain was no more than a peninsula of Europe, its north capped in ice, and its south a polar desert.

In Africa and the Middle East, many smaller mountain glaciers formed, and the Sahara, Gobi, and other sandy deserts were greatly expanded in extent.

The Persian Gulf averages about 35 metres in depth with the seabed between Abu Dhabi and Qatar even shallower, for the most part less than 15 metres deep. For thousands of years the Ur-Shatt (a confluence of the Tigris-Euphrates Rivers) provided fresh water to the Gulf, as it flowed through the Strait of Hormuz into the Gulf of Oman.

Bathymetric data suggests there were two palaeo-basins in the Persian Gulf. The central basin may have approached an area of 20,000 km², comparable at its fullest extent to lakes such as Lake Malawi in Africa. Between 12,000 and 9000 years ago much of the Gulf floor would have remained exposed, only becoming subject to marine transgression after 8,000 years ago.

The Magdalenian (French: Magdalénien), refers to one of the later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic in western Europe towards the end of the last ice age, dating from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madeleine, a rock shelter located in the Vézère valley, commune of Tursac, in the Dordogne department of France.

Originally termed “L’âge du renne” (the Age of the Reindeer) by Édouard Lartet and Henry Christy, the first systematic excavators of the type site, in their publication of 1875, the Magdalenian is synonymous in many people’s minds with reindeer hunters, although Magdalenian sites also contain extensive evidence for the hunting of red deer, horse and other large mammals present in Europe towards the end of the last ice age. The culture was geographically widespread, and later Magdalenian sites have been found from Portugal in the west to Poland in the east.

There is extensive debate about the precise nature of the earliest Magdalenian assemblages, and it remains questionable whether the Badegoulian culture is in fact the earliest phase of the Magdalenian. Similarly finds from the forest of Beauregard near Paris have often been suggested as belonging to the earliest Magdalenian. The earliest Magdalenian sites are all found in France. The Epigravettian is another similar culture appearing during the same period in Italy and Eastern Europe (Moldavia, Romania).

The later phases of the Magdalenian are also synonymous with the human re-settlement of north-western Europe after the Last Glacial Maximum during the Late Glacial Maximum. Research in Switzerland, southern Germany and Belgium has provided AMS radiocarbon dating to support this. However being hunter gatherers Magdalenians did not simply re-settle permanently in north-west Europe as they often followed herds and moved depending on seasons.

By the end of the Magdalenian, the lithic technology shows a pronounced trend towards increased microlithisation. The bone harpoons and points have the most distinctive chronological markers within the typological sequence. As well as flint tools, the Magdalenians are best known for their elaborate worked bone, antler and ivory which served both functional and aesthetic purposes including perforated batons. Examples of Magdalenian portable art include batons, figurines and intricately engraved projectile points, as well as items of personal adornment including sea shells, perforated carnivore teeth (presumably necklaces) and fossils.

The sea shells and fossils found in Magdalenian sites can be sourced to relatively precise areas of origin, and so have been used to support hypothesis of Magdalenian hunter-gatherer seasonal ranges, and perhaps trade routes. Cave sites such as the world famous Lascaux contain the best known examples of Magdalenian cave art. The site of Altamira in Spain, with its extensive and varied forms of Magdalenian mobillary art has been suggested to be an agglomeration site where multiple small groups of Magdalenian hunter-gatherers congregated.

In northern Spain and south west France it was superseded by the Azilian culture. In northern Europe we see a slightly different picture, with different variants of the Tjongerian techno-complex following it.

It has been suggested that key Late Glacial sites in south-western Britain can also be attributed to the Magdalenian, including the famous site of Kent’s Cavern, although this remains open to debate.

The Federmesser culture or Federmesser group is a toolmaking tradition of the late Upper Palaeolithic era, of the Northern European Plain from Poland (where the culture is called Tarnowian and Witowian) to northern France, dating to between c. 12000 and 10800 BC (uncalibrated). It is closely related to the Tjongerian culture, as both have been suggested as being part of the more generalized Azilian culture.

It used small backed flint blades, from which its name derives (Federmesser is German for “feather knife”), and shares characteristics with the Creswellian culture, a British Upper Palaeolithic culture named after the type site of Creswell Crags in Derbyshire. The Creswellian dates from c. 13.000 to 11,500 BP and was replaced by the Ahrensburg culture (11th to 10th millennia BCE).

Ahrenburg culture was a late Upper Paleolithic and early Mesolithic (or Epipaleolithic) nomadic hunter culture (or technocomplex) in north-central Europe during the Younger Dryas, the last spell of cold at the end of the Weichsel glaciation resulting in deforestation and the formation of a tundra with bushy arctic white birch and rowan, that started with the glacial recession and the subsequent disintegration of Late Palaeolithic cultures between 15,000 and 10,000 calBC.

Northward migrations coincided with the warm Bølling and Allerød events, but much of northern Eurasia remained inhabited during the Younger Dryas. The extinction of mammoth and other megafauna provided for an incentive to exploit other forms of subsistence that included maritime resources. During the holocene climatic optimum, the increased biomass led to a marked intensification in foraging by all groups, the development of inter-group contacts, and ultimately, the initiation of agriculture.

The most important prey was the wild reindeer. The earliest definite finds of arrow and bow date to this culture, though these weapons might have been invented earlier. The Ahrensburgian was preceded by the Hamburg and Federmesser cultures and superseded by mesolithic cultures (Maglemosian). Ahrensburgian finds were made in southern and western Scandinavia, the North German plain and western Poland. The Ahrensburgian area also included vast stretches of land now at the bottom of the North and Baltic Sea, since during the Younger Dryas the coastline took a much more northern course than today.

The culture is named after a tunnel valley near the village of Ahrensburg, 25 km (16 mi) northeast of Hamburg in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, where Ahrensburg find layers were excavated in Meiendorf, Stellmoor and Borneck. While these as well as the majority of other find sites date to the Young Dryas, the Ahrensburgian find layer in Alt Duvenstedt has been dated to the very late Allerød, thus possibly representing an early stage of Ahrensburgian which might have corresponded to the Bromme culture in the north. Artefacts with tanged points are found associated with both the Bromme and the Ahrensburg cultures.

The different technolithic complexes are chronologically associated with the climatic chronozones. The re-colonisation of Northern Germany is connected to the onset of the late Glacial Interstadial between Weichsel and the Dryas I glaciation, at the beginning of the Meiendorf Interstadial around 12.700 calBC.

Palynological results demonstrate a close connection between the prominent temperature rise at the beginning of the Interstadial and the expansion of the hunter-gatherers into the northern Lowlands. The existence of a primary “pioneer phase” in the re-colonisation is contradicted by proof of e.g. an early Central European Magdalenian in Poland.

Today it is commonly accepted that the Hamburgian, featured by “Shouldered Point” lithics, is a techno-complex closely related to the Creswellian and rooted in the Magdalenian. Within the Hamburgian techno-complex, a younger dating is found for the Havelte phase, sometimes interpreted as a northwestern phenomenon, perhaps oriented towards the former coastline.

The Hamburgian culture existed during the warm Bølling period, the brief Dryas II glaciation (lasting 300 years) and in the early warmer Allerød period.

However, the distribution of the Hamburgian east of the Oder River has been confirmed and Hamburgian culture can also be distinguished in Lithuania. Finds in Jutland indicates the expansion of early Hamburgian hunters and gatherers reached further north than previously expected. The Hamburgian sites with shouldered point lithics reach as far north as the Pomeranian ice margin. The younger Havelte phase has been proven for the area beyond the Pomeranian ice margin and on the Danish Isles after circa 12.300 calBC.

The “Backed Point” lithics of Federmesser culture are usually dated in the Allerød Interstadial. Early Federmesser finds follows shortly or are contemporary to Havelte. The culture lasted approximately 1200 years from 11.900 to 10.700 calBC., and is located in Northern Germany and Poland to south Lithuania. Fish-hooks were discovered in Allerød layers and emphasize the importance of fishing in the Late Palaeolithic. A certain survival of late Upper Palaeolithic traditions similar to contemporary Azilian (France, Spain) becomes apparent, such as the amber elk from Weitsche that can be considered as a link to the Mesolithic, amber animal sculptures.

Bromme culture sites are found in the entire southern and southeastern Baltic, and are dated to the second half of Allerød and the early cold Dryas III period. The “classical” Brommian complex is typified by simple and fast, but uneconomical, flint processing using unipolair cores. A new development noticed in Lithuania introduced both massive and smaller “Tanged Points”.

In Bromme culture this technology is proposed to be an innovation derived from tanged Havelte groups. As such, derivation of Bromme culture and even migration of its representatives from the territories of Denmark and northern Germany have been proposed, although other sources hold early Bromme not to be very well defined in (late Allerød) Northern Germany, where it groups with Federmesser.

Ahrensburg culture is normally associated with the Younger Dryas glacialization and the Pre-boreal period. The traditional view of the Ahrensburg culture being a direct inheritor of the Bromme culture in the late Dryas period is contradicted by new information that the Ahrensburgian techno-complex probably already started before the Younger Dryas, strengthening proposals to a direct derivation from the Havelte stage of the Hamburg culture.

Some recent finds, such as the Hintersee 24 site in southern Landkreis Vorpommern-Greifswald, would contribute to the argument of an early Ahrensburgian in northern Germany. Alternatively, flint artefacts of Bromme tanged-point groups is considered to prelude the techno-complex of the Ahrensburg culture and would point to the provenience of Ahrensburg from Bromme culture. As such, the Grensk culture in Bromme territory at the source of the Dnieper River was proposed to be the direct originator of Ahrensburgian culture.

However, the exact typological chronology of this culture is still unclear. Though associated with the Bromme complex, Grensk culture has its roots more defined in the local Mammoth Hunters’ culture.

Another possibility derives from the observation that on a regional scale, the Hamburgian culture is succeeded geographically as well as chronologically by the Federmesser culture, or Arch-Backed Piece Complex. The existence of a genuine Federmesser occupation in southern Scandinavia is highly controversial, and there is wide, though not unanimous, agreement that some Federmesser types constitute an integral part of the early Brommean artefact inventory.

Still, Federmesser types are also often found in close association with Hamburgian assemblages (e.g. at Slotseng and Sølbjerg) and tentative, dating from northern Germany shows some degree of contemporaneity between the late Hamburgian Havelte sites and the Federmesser ones. Therefore in southern Scandinavia the Federmesser may represent a brief transitory phase between the Hamburgian and the Brommean.

This corresponds with the notion that “tanged point cultures” such as “Brommian” or “Bromme-Lyngby” appear to be based on the Magdalenian, during the Allerød and were closely associated with reindeer hunting.

Stellmoor was a seasonal settlement inhabited primarily during October, and bones from 650 reindeer have been found there. The hunting tool was bow and arrow. From Stellmoor there are also well-preserved arrow shafts of pine intended for the culture’s characteristic skaftunge arrowheads of flintstone. A number of intact reindeer skeletons, with arrowheads in the chest, has been found, and they were probably sacrifices to higher powers. At the settlements, archaeologists have found circles of stone, which probably were the foundations of hide teepees.

The earliest reliable traces of habitation in the northern territories of Norway and western Sweden date to the transition period from the Younger Dryas to the Preboreal. More favourable living conditions, and past experience gained through seasonal rounds, prompted increased maritime resource exploitation in the northern territories.

The Hensbacka group on the west coast of Sweden exemplifies the cultural fragmentation process that took place within the Continental Ahrensburgian. Instead of new immigrations at the beginning of the Mesolithic, the discovery of deposited bones and new dating indicate that there was no (significant) break in settlement continuity. New knowledge provides aspects for a further autochthonous development, with a rapid climatic change stimulating a swift cultural change.

The Human Journey: Early Settlements in Europe

Links on the Gravettians of the Ice Age

Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures

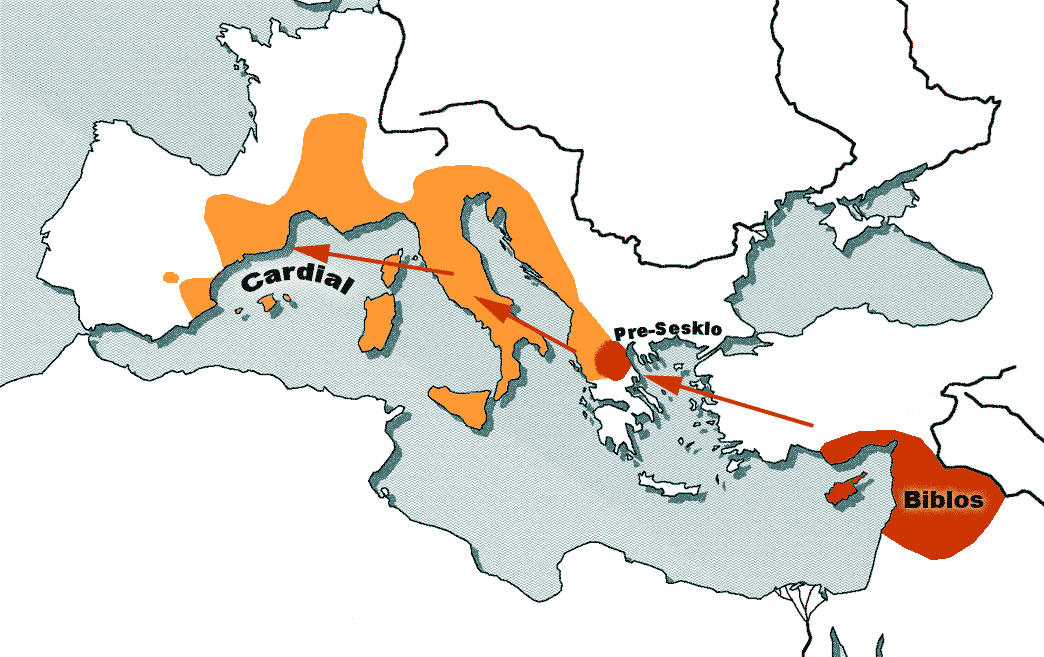

The Neolithic cultures

Filed under: Uncategorized