The Budini (Greek: Boudinoi) were an ancient people who lived in Scythia, in what is today Ukraine. In his account of Scythia (Inquiries book 4), Herodotus writes that the Geloni were formerly Greeks, having settled away from the coastal emporia among the Budini, where they “use a tongue partly Scythian and partly Greek”:

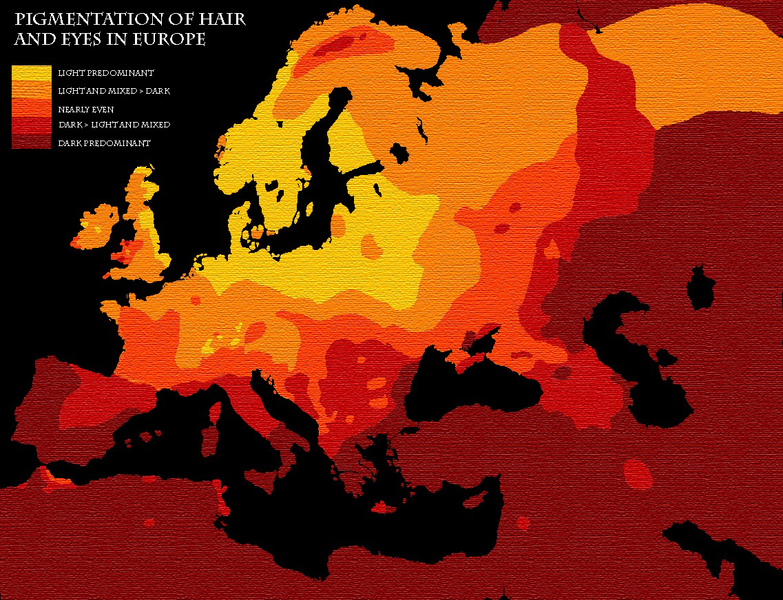

“The Budini for their part, being a large and numerous nation, is all mightily blue-eyed and ruddy. And a city among them has been built, a wooden city, and the name of the city is Gelonus.

Of its wall then in size each side is of thirty stades and high and all wooden. And their homes are wooden and their shrines. For indeed there is in the very place Greek gods’ shrines adorned in the Greek way with statues, altars and wooden shrines and for triennial Dionysus festivals in honour of Dionysus.”

“Above the Sauromatae (Sarmatians), possessing the second region, dwell the Budini, whose territory is thickly wooded with trees of every kind. The Budini are a large and powerful nation: they have all deep blue eyes, and bright red hair.

The Budini, however, do not speak the same language as the Geloni, nor is their mode of life the same. They are the aboriginal people of the country, and are nomads; unlike any of the neighbouring races, they eat lice.

Their country is thickly planted with trees of all manner of kinds. In the very woodiest part is a broad deep lake, surrounded by marshy ground with reeds growing on it. Here otters are caught, and beavers, with another sort of animal which has a square face.

With the skins of this last the natives border their capotes: and they also get from them a remedy, which is of virtue in diseases of the womb… Beyond the Budini, as one goes northward, first there is a desert, seven days’ journey across…”

The fortified settlement of Gelonus was reached by the Persian army of Darius in his assault on Scythia during the 5th century BC, already burned to the ground, the Budini having abandoned it before the Persian advance.

The Scythians sent a message to Darius: “We are free as wind and what you can catch in our land is only the wind”. By employing a scorched earth strategy, they avoided battles, leaving “earth without grass” by burning the steppe in front of the advancing Persians (Herodotus). The Persian army returned without a single battle or any significant success.

Later located eastward probably on the middle course of the Volga about Samara, the Budini are described as fair-eyed and red-haired, and lived by hunting in the dense forests. In their country was a wooden city called Gelonos, inhabited with a “distinct race”, the Geloni, who according to Herodotus were Greeks that became assimilated to the Scythians. Later writers add nothing to our knowledge of the Budini, and are more interested in the tarandus, an animal that dwelt in the woods of the Budini, possibly the reindeer (Aristotle ap. Aelian, Hist. Anim. xv. 33).

Red hair is the rarest natural hair color in humans. The non-tanning skin associated with red hair may have been advantageous in far-northern climates where sunlight is scarce. Studies by Bodmer and Cavalli-Sforza (1976) hypothesized that lighter skin pigmentation prevents rickets in colder climates by encouraging higher levels of Vitamin D production and also allows the individual to retain heat better than someone with darker skin.

In 2000, Harding et al. concluded that red hair was not the result of positive selection and instead proposed that it occurs because of a lack of negative selection. In Africa, for example, red hair is selected against because high levels of sun would be harmful to untanned skin. However, in Northern Europe this does not happen, so redheads come about through genetic drift.

According to some researchers, the Budinis were a Finnic tribe ruled by the Scythians. The 1911 Britannica surmises that they were Fenno-Ugric, of the branch now represented by the Udmurts and Komis (this branch is now called “Permic”), forced northwards by later immigrants. Edgar V. Saks identifies Budini as Votic people, a people of Votia in Ingria, the part of modern-day northwestern Russia that is roughly southwest of Saint Petersburg and east of the Estonian border-town of Narva.

Udmurts

The Udmurts are a people who speak the Udmurt language. Through history they have been known in Russian as Chud Otyatskaya, Otyaks, or Votyaks (most known name), and in Tatar as Ar. The Udmurt language belongs to the Uralic family.

The name Udmurt probably comes from *odo-mort ‘meadow people,’ where the first part represents the Permic root *od(o) ‘meadow, glade, turf, greenery’ (related to Finnish itää ‘to germinate, sprout’) and the second part (Udmurt murt ‘person’; cf. Komi mort, Mari mari) is an early borrowing from Indo-Iranian *mertā or *martiya ‘person, man’ (cf. Urdu/Persian mard). This is supported by a document dated Feb. 25, 1557, in which alongside the traditional Russian name otyaki the Udmurts are referred to as lugovye lyudi ‘meadow people’.

On the other hand, in the Russian tradition, the name ‘meadow people’ refers to the inhabitants of the left bank of river general. Recently, the most relevant is the version of V. V. Napolskikh and S. K. Belykh. They suppose that ethnonym was borrowed from the Iranian entirely: *anta-marta ‘resident of outskirts, border zone’ (cf. Antes) → Proto-Permic *odə-mort → Udmurt udmurt.

Anthropologists relate Udmurts to the Urals branch of Europeans. Most of them are of the middle size, often have blue or gray eyes, high cheek-bones and wide face. The Udmurt people are not of an athletic build but they are very hardy. and there have been claims that they are the “most red-headed” people in the world. Additionally, the ancient Budini tribe, which is speculated to be an ancestor of the modern Udmurts, were described by Herodotus as being predominantly red-headed.

Most Udmurt people live in Udmurtia. Small groups live in the neighboring areas: Kirov Oblast and Perm Krai of Russia, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, and Mari El. The Udmurt population is shrinking; the Russian census reported 637,000 of them in 2002, compared to 746,562 in 1989.

Komi

Based on linguistic reconstruction, the prehistoric Permians are assumed to have split into two peoples during the first millennium BC: the Komis and the Udmurts. Around 500 AD, the Komis further divided into the Komi-Permyaks (who remained in the Kama River basin) and the Komi-Zyrians (who migrated north).

The name “Komi” may come from the Udmurt word “kam” (meaning “large river”, particularly the River Kama) or the Udmurt “kum” (meaning “kinfolk”). The scholar Paula Kokkonen favours the derivation “people of the Kama”. The name “Zyrian” is disputed, but may be from a personal name Zyran.

The Komi or Zyrian people is an ethnic group whose homeland is in the north-east of European Russia around the basins of the Vychegda, Pechora and Kama rivers. They mostly live in the Komi Republic, Perm Krai, Murmansk Oblast, Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug in the Russian Federation. They belong to the Permian branch of the Uralic peoples.

The Komis are divided into eight sub-groups. Their northernmost sub-group is also known as the Komi-Izhemtsy (from the name of the river Izhma) or Iz’vataz. This group numbers 15,607. This group is distinct for its more traditional, strongly subsistence based economy which includes reindeer husbandry. Komi-Permyaks (125,235 people) live in Perm Krai (Komi-Yazvas group) and Kirov Oblast (Upper-Kama Komi group) of Russia.

The Komi language belongs to the Permian branch of the Uralic family. There is limited mutual intelligibility with Udmurt. There are three main dialects: Pechora, Udor and Verkhne-Vyshegod. Until the 18th century, Komi was written in the Old Permic alphabet introduced by Saint Stephen of Perm in the 14th century. Cyrillic was used from the 19th century and briefly replaced by the Latin alphabet between 1929 and 1933. The Komi language is currently written in Cyrillic, adding two extra letters – Іі and Ӧӧ – to represent vowel sounds which do not exist in Russian. The first book to be printed in Komi (a vaccination manual) appeared in 1815.

From the 12th century the Russians began to expand into the Perm region and the Komis came into contact with Novgorod. Novgorodian traders travelled to the region in search of furs and animal hides.

The Novgorodians referred to the southern Komi region as “the Great Perm”. Komi dukes unified the Great Perm with its centre at the stronghold of Cherdyn. As the Middle Ages progressed, Novgorod gave way to Moscow as the leading Russian power in the region.

In 1365, Dmitry Donskoy, Prince of Moscow, gave Stephen of Perm the task of converting the region to Christianity. Stephen’s mission led to the creation of the eparchy of Perm in 1383 and, after his death, Stephen became the patron saint of the Komis. He also devised an alphabet for the Komi language.

Nevertheless, some Komis resisted Christianisation, notably the shaman Pama. The Duke of Perm only accepted baptism in 1470 (he was given the Christian name Mikhail), possibly in an attempt to stave off Russian military pressure in the region.

Mikhail’s conversion failed to stop an attack by Moscow which seized Cherdyn in 1472. Mikhail was allowed to keep his title of duke but was now a vassal of Moscow. The duchy only survived until 1505 when Mikhail’s son Matvei was replaced by a Russian governor and Komi independence came to an end.

In the 1500s many Russian migrants began to move into the region, beginning a long process of colonisation and attempts at assimilating the Komis. Syktyvkar was founded as the chief Russian city in the region in the 18th century. The Russian government established penal settlements in the north for criminals and political prisoners.

There were several Komi rebellions in protest against Russian rule and the influx of Slav settlers, especially after large numbers of freed serfs arrived in the region from the 1860s. A national movement to revive Komi culture also emerged.

Russian rule in the area collapsed after World War I and the revolutions of 1917. In the subsequent Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks fought the Allies for control of the region. The Allied interventionist forces encouraged the Komis to set up their own independent state with the help of political prisoners freed from the local penal colonies.

After the Allies withdrew in 1919, the Bolsheviks took over. They promoted Komi culture but increased industrialisation damaged the Komis’ traditional way of life. Stalin’s purges of the 1930s devastated the Komi intelligentsia, who were accused of “bourgeois nationalism”.

The remote and inhospitable region was also regarded as an ideal location for the prison camps of the Gulag. The influx of political prisoners and the rapid industrialisation of the region as a result of World War II left the Komis a minority in their own lands.

Stalin carried out further purges of the Komi intellectual class in the 1940s and 1950s, and Komi language and culture was suppressed. Since the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Komis have reasserted their claims to a separate identity.

Most Komis belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, but their religion often contains traces of pre-Christian beliefs of the traditional mythology of the Komi people of northern Russia. A large number of Komis are Old Believers, which are Christians that separated after 1666 from the official Russian Orthodox Church as a protest against church reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon between 1652 and 1666. Old Believers continue liturgical practices which the Russian Orthodox Church maintained before the implementation of these reforms.

Votes

Votes are the oldest known ethnic group in Ingria. They are probably descended from an Iron-age population of north-eastern Estonia and western Ingria. Some scientists claim they were a tribe of Estonians, who developed a separate identity during isolation from other Estonians. It is speculated the ancient Estonian county of Vaiga got its name from Votians. The Kylfings, a people active in Northern Europe during the Viking Age, may have also been Votes.

Earliest literary references of Votes by their traditional name are from middle-age Russian sources, where Votes are referred to as Voď. They were previously considered Chudes together with Estonians in Russian sources, and Lake Peipus near Votian homelands is called Chudsko ozero, meaning “Lake of Chudes” in Russian.

Veliky Novgorod (also Novgorod the Great), or just Novgorod, is one of the oldest cities of Russia, founded in the 9th or 10th century, and most important historic cities in Russia. It serves as the administrative center of Novgorod Oblast. It is situated on the M10 federal highway connecting Moscow and St. Petersburg. The city lies along the Volkhov River just downstream from its outflow from Lake Ilmen. UNESCO recognised Novgorod as a World Heritage Site in 1992.

The Sofia First Chronicle first mentions it in 859; the Novgorod First Chronicle mentions it first in the year 862, when it was allegedly already a major station on the trade route from the Baltics to Byzantium.

Archaeological excavations in the middle to late 20th century, however, have found cultural layers dating back only to the late 10th century, the time of the Christianization of Rus’ and a century after it was allegedly founded, suggesting that the chronicle entries mentioning Novgorod in the 850s or 860s are later interpolations.

In 1069 Votes were mentioned taking part in an attack on the Novgorod Republic by the Principality of Polotsk. Eventually Votes became part of the Novgorod Republic and in 1149 they were mentioned taking part in an attack by Novgorod against Jems who are speculated to be peoples of Tavastia. One of the administrative divisions of Novgorod, Voch’skaa, was named after Votes. After the collapse of Novgorod, the Grand Duchy of Moscow deported many Votes from their homelands and began more aggressive conversion of them.

Missionary efforts started in 1534, after Novgorod’s archbishop Macarius complained to Ivan IV that Votes were still practicing their pagan beliefs. Makarius was authorized to send monk Ilja to convert the Votes. Ilja destroyed many of the old holy shrines and worshiping places. Conversion was slow and the next archbishop Feodosii had to send priest Nikifor to continue Ilja’s work. Slowly Votes were converted and they became devoted Christians.

Sweden controlled Ingria in the 17th century, and attempts to convert local Orthodox believers to the Lutheran faith caused some of the Orthodox population to migrate elsewhere. At the same time many Finnish peoples immigrated to Ingria. Religion separated the Lutheran Finns and Orthodox Izhorians and Votes, so intermarriage was uncommon between these groups. Votes mainly married other Votes, or Izhorians and Russians. They were mostly trilingual in Votic, Izhoran and Russian.

Ingrian (also called Izhorian) is a nearly extinct Finnic language spoken by the (mainly Orthodox) Izhorians of Ingria. It has approximately 120 speakers left, most of whom are aging. It should not be confused with the Southeastern dialects of the Finnish language that became the majority language of Ingria in the 17th century with the influx of Lutheran Finnish immigrants (whose descendants, Ingrian Finns, are often referred to as Ingrians).

The immigration of Lutheran Finns was promoted by Swedish authorities (who gained the area from Russia in 1617), as the local population was (and remained) Orthodox.

In 1848, the number of Votes had been 5,148, (Ariste 1981: 78). but in the Russian census of 1926 there were only 705 left. From the early 20th century on, the Votic language no longer passed to following generations. Most Votes were evacuated to Finland along with Finnish Ingrians during World War II, but were returned to the Soviet Union later.

As a distinct people, Votes have become practically extinct after Stalinist dispersion to distant Soviet provinces as ‘punishment’ for alleged disloyalty and cowardice during World War II. Expelees allowed to return in 1956 found their old homes occupied by Russians.

In 1989, there were still 62 known Votes left, with the youngest born in 1930. There were 73 self-declared Votes in the 2002 Russian census. Of them 12 lived in St. Petersburg, 12 in Leningrad Oblast and 10 in Moscow. In 2008 Votes were added to the list of Indigenous peoples of Russia, granting them some support to preserving their culture.

There have been some conflicts with Votic villagers and foresters, and in 2001 the Votic museum was burned in the village of Lužitsõ. Another possible problem is a port which is being constructed to Ust-Luga. It is planned that some 35,000 people would move near historic Votic and Izhoran villages.

The Votes in Latvia were called krieviņi in Latvian. The word comes from krievs, which means “Russian”. Historical sources indicate the Teutonic Knights led by Vinke von Overberg captured many people in Ingermanland during their attack there in 1444–1447, and moved them to Bauska, where a workforce was needed to build a castle. It is estimated that some 3,000 people were transferred there. After the castle was built, the Votes did not go back, but were settled in the vicinity of Bauska and became farmers.

Gradually, they forgot their own language and customs and were assimilated by the neighboring Latvians. They are first mentioned in literature of 1636. The first “modern” scientist to study them was Finnish Anders Johan Sjögren, but the first person to connect them with Votes was Ferdinand Johan Wiedemann in 1872. Latvian poet Jānis Rainis had some Votic roots.

Most Votes were able to speak Izhorian and Russian as well as the Votic language. In fact, Izhorian was more common in every day use than Votic in some villages. Votic was commonly used with family members, while Russian and Izhorian were used with others. Russian was the only language used in Churches. Votes often referred to themselves as Izores, since this term was more commonly known among others. The term came in use when people wanted to make a difference between Lutheran and Orthodox Finnic populations in Ingria.

The Votic language is still spoken in three villages of historical Votia and by an unknown number of fluent Votic speakers in the countryside. The villages are Jõgõperä (Krakolye), Liivcülä (Peski), and Luuditsa (Luzhitsy).

Filed under: Uncategorized