![]()

![]()

![]()

Hvor kommer Odin fra?

Odin/Frigg (sky) – óðr/Freyja (earth) (Sumerian: An/Antu-Inanna)

Balder/Nanna (Sumerian: Tammuz/Inanna)

Šamaš (Sumerian Utu) is the god of the sun, who was associated with life, justice, divination and the netherworld).

Cronus (Enlil, Saturn, Odin) – The second sun

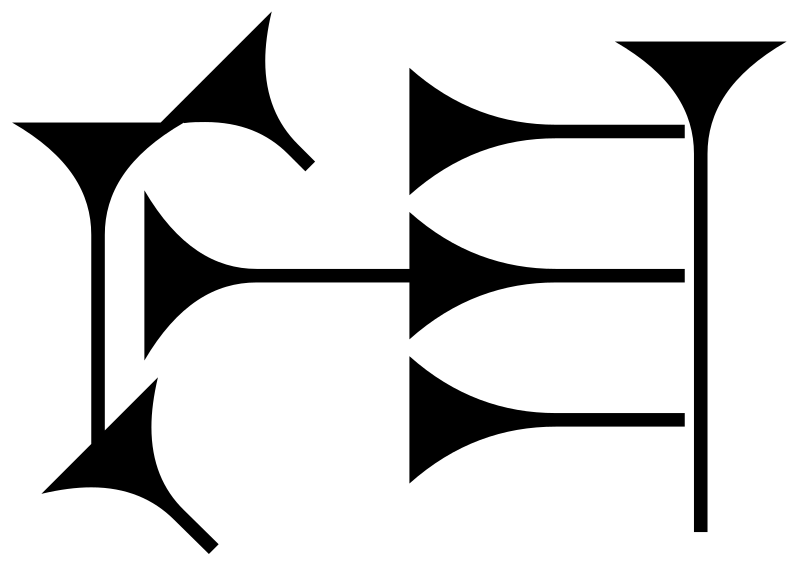

Odin – Sumerian UD (“sun”)

Ud

Arinna was the major cult center of the Hittite sun goddess, (thought to be Arinniti) known as UTU Arinna “sun goddess of Arinna”. Arinna was located near Hattusa, the Hittite capital. The name was also used as a substitute name for Arinniti.

The sun goddess of Arinna is the most important one of three important solar deities of the Hittite pantheon, besides UTU nepisas – “the sun of the sky” and UTU taknas – “the sun of the earth”. She was considered to be the chief deity in some source, in place of her husband. Her consort was the weather god, Teshub. The goddess was also perceived to be a paramount chthonic or earth goddess. She becomes largely syncretised with the Hurrian goddess Hebat.

Utu (Akkadian rendition of Sumerian UD “Sun”, Assyro-Babylonian Shamash “Sun”) is the Sun god in Sumerian mythology, the son of the moon god Nanna and the goddess Ningal. His brother and sisters are Ishkur and the twins Inanna and Ereshkigal. His center cult was located in the city of Larsa.

Utu is the god of the sun, justice, application of law, and the lord of truth. He is usually depicted as wearing a horned helmet and carrying a saw-edged weapon not unlike a pruning saw. It is thought that every day, Utu emerges from a mountain in the east, symbolizing dawn, and travels either via chariot or boat across the Earth, returning to a hole in a mountain in the west, symbolizing sunset. Every night, Utu descends into the underworld to decide the fate of the dead. He is also depicted as carrying a mace, and standing with one foot on a mountain. Its symbol is “sun rays from the shoulders, and or sun disk or a saw”.

The sun god is only modestly mentioned in Sumerian mythology with one of the notable exceptions being the Epic of Gilgamesh. In the myth, Gilgamesh seeks to establish his name with the assistance of Utu, because of his connection with the cedar mountain. Gilgamesh and his father, Lugalbanda were kings of the first dynasty of Uruk, a lineage that Jeffrey H. Tigay suggested could be traced back to Utu himself.

He further suggested that Lugalbanda’s association with the sun-god in the Old Babylonian version of the epic strengthened “the impression that at one point in the history of the tradition the sun-god was also invoked as an ancestor”. Marduk is spelled AMAR.UTU in Sumerian, literally, “the calf of Utu” or “the young bull of the Sun”.

Mashu

Mashu, as described in the Epic of Gilgamesh of Mesopotamian mythology, is a great cedar mountain through which the hero-king Gilgamesh passes via a tunnel on his journey to Dilmun after leaving the Cedar Forest, a forest of ten thousand leagues span.

The corresponding location in reality has been the topic of speculation, as no confirming evidence has been found. Jeffrey H. Tigay suggests that in the Sumerian version, through its association with the sun god Utu, “(t)he Cedar Mountain is implicitely located in the east, whereas in the Akkadian versions, Gilgamesh’s destination (is) removed from the east” and “explicitly located in the north west, in or near Lebanon”.

One theory is that the only location suitable for being called a “cedar land” was the great forest covering Lebanon and western parts of Syria and, in consequence, “Mashu” is the whole of the parallel Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges, with the narrow gap between these mountains constituting the tunnel.

The word “Mashu” itself may translate as “two mountains”, from the Babylonian for twins. The “twins”, in Semitic mythology, were also often seen as two mountains, one at the eastern edge of the world (in the lower Zagros), the other at the western edge of the world (in the Taurus), and one of these seem to have had an Iranian location.

Mashu, today, is a village in the Elburz mountains of Iran. Siduri, the Alewife, lived on the shore, associated with “the Waters of Death” that Gilgamesh had to cross to reach Utnapishtim, the far-away. Masis is the Armenian name for the peak of Ararat, the plural ‘Masiq’ may refer to both peaks. The History of Armenia derives the name from a king Amasya, the great-grandson of the Armenian patriarch Hayk, who is said to have called the mountain Masis after himself.

Edin/Aten-Aton

Edin (É.DIN, E2.DIN, E-din) is a Sumerian term meaning “steppe” or “plain”. It is featured on the Gudea cylinders as the name of a watercourse from which plaster is taken to build a temple for Ningirsu.

Friedrich Delitzsch was the first amongst numerous scholars to suggest the Jewish and Christian term Eden, “garden of God”, traced back to this term. It has also been connected with the later Babylonian term “Edinu”.

Traditionally, the favoured derivation of the name “Eden” was from the Akkadian edinnu, derived from a Sumerian word meaning “plain” or “steppe”. Eden is now believed to be more closely related to an Aramaic root word meaning “fruitful, well-watered.” The Hebrew term is translated “pleasure” in Sarah’s secret saying in Genesis 18:12.

Aten

Principles of Aten’s religion were recorded on the rock tomb walls of Akhetaten. In the religion of Aten (Atenism), night is a time to fear. Work is done best when the sun, Aten, is present. The explanation to why Aten could not be fully represented was that the god has gone beyond creation.

Aten cares for every creature, and created a Nile river in the sky (rain) for the Syrians. Aten created all countries and people. The rays of the sun disk only hold out life to the royal family; everyone else receives life from Akhenaten and Nefertiti in exchange of loyalty for Aten.

When a good person dies, he/she continues to live in the City of Light for the dead in Akhetaten. The conditions are the same after death. Akhenaten judged whether someone should be granted an afterlife, and operated the scale of justice.

An/Antu-Inanna

The purely theoretical character of An is thus still further emphasized, and in the annals and votive inscriptions as well as in the incantations and hymns, he is rarely introduced as an active force to whom a personal appeal can be made. His name becomes little more than a synonym for the heavens in general and even his title as king or father of the gods has little of the personal element in it.

A consort Antu is assigned to him, on the theory that every deity must have a female associate. But Anu spent so much time on the ground protecting the Sumerians he left her in Heaven and then met Innin (Inanna), whom he renamed Innan, or, “Queen of Heaven”. An resided in her temple the most, and rarely went back up to Heaven.

Odin

The Old Norse theonym Óðinn (popularly anglicized as Odin) and its cognates, including Old English Wóden, Old Saxon Wōden, and Old High German Wuotan, derive from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic theonym *wōđanaz.

The masculine noun *wōđanaz developed from the Proto-Germanic adjective *wōđaz, related to Latin vātēs and Old Irish fáith, both meaning ‘seer, prophet’. Adjectives stemming from *wōđaz include Gothic woþs ‘possessed’, Old Norse óðr, ‘mad, frantic, furious’, and Old English wód ‘mad’.

The adjective *wōđaz (or *wōđō) was further substantivized, leading to Old Norse óðr ‘mind, wit, soul, sense’, Old English ellen-wód ‘zeal’, Middle Dutch woet ‘madness’, and Old High German wuot ‘thrill, violent agitation’.

Additionally the Old Norse noun æði ‘rage, fury’ and Old High German wuotī ‘madness’ derive from the feminine noun *wōđīn, from *wōđaz. The weak verb *wōđjanan, also derived from *wōđaz, gave rise to Old Norse æða ‘to rage’, Old English wédan ‘to be mad, furious’, Old Saxon wōdian ‘to rage’, and Old High German wuoten ‘to be insane, to rage’.

Over 170 names are recorded for the god Odin. These names are variously descriptive of attributes of the god, refer to myths involving him, or refer to religious practices associated with the god. This multitude of names makes Odin the god with the most names known among the Germanic peoples.

Wednesday

The weekday name Wednesday derives from the Old English name of the god: ‘Woden’s day’. Cognate terms are found in other Germanic languages, such as Old High German wōdnesdæg, Middle Low German wōdensdach (Dutch Woensdag), and Old Norse Óðinsdagr (Danish, Norwegian and Swedish Onsdag).

All of these terms derive from Proto-Germanic *Wodensdag, itself Germanic interpretation of Latin Dies Mercurii (“Day of Mercury”). While other day names containing Germanic theonyms remained into Old High German, the name derived from Odin’s was replaced by a translation of Church Latin media hebdomas ‘middle of the week’ (modern German Mittwoch).

The name Wednesday continues Middle English Wednesdei. Old English still had wōdnesdæg, which would be continued as *Wodnesday (but Old Frisian has an attested wednesdei). By the early 13th century, the i-mutated form was introduced unetymologically.

The name is a calque of the Latin dies Mercurii “day of Mercury”, reflecting the fact that the Germanic god Woden (Wodanaz or Odin) during the Roman era was interpreted as “Germanic Mercury”.

The Latin name dates to the late 2nd or early 3rd century. It is a calque of Greek ἡμέρα Ἕρμου heméra Hérmou, a term first attested, together with the system of naming the seven weekdays after the seven classical planets, in the Anthologiarum by Vettius Valens (ca. AD 170).

The Latin name is reflected directly in the weekday name in Romance languages: Mércuris (Sardinian), mercredi (French), mercoledì (Italian), miércoles (Spanish), miercuri (Romanian), dimecres (Catalan), Marcuri or Mercuri (Corsican), dies Mercurii (Latin). The German name for the day, Mittwoch (literally: “mid-week”), replaced the former name Wodenstag (“Wodan’s day”) in the tenth century. The Dutch name for the day, woensdag has the same etymology as English Wednesday, it comes from Middle Dutch wodenesdag, woedensdag (“Wodan’s day”).

Most Slavic languages follow this pattern and use derivations of “the middle” (Bulgarian сряда sryada, Croatian srijeda, Czech středa, Macedonian среда sreda, Polish środa, Russian среда sredá, Serbian среда/sreda or cриједа/srijeda, Slovak streda, Slovene sreda, Ukrainian середа sereda).

The Finnish name is Keskiviikko (“middle of the week”), as is the Icelandic name: Miðvikudagur, and the Faroese name: Mikudagur (“Mid-week day”). Some dialects of Faroese have Ónsdagur, though, which shares etymology with Wednesday. Danish, Norwegian, Swedish Onsdag, (“Ons-dag” = Oden’s/Odin’s dag/day). In Welsh it is Dydd Mercher, meaning Mercury’s Day.

In Japanese, the word Wednesday is sui youbi, meaning ‘water day’ and is associated with suisei: Mercury (the planet), literally meaning “water star”. Similarly, in Korean the word Wednesday is su yo il, also meaning water day.

In most of the languages of India, the word for Wednesday is Budhavãra—vãra meaning day and Budh being the planet Mercury.

From Armenian chorekshabti, Georgian othshabati, and Tajik (Chorshanbiyev) languages the word literally means as “four (days) from Saturday”.

Portuguese uses the word quarta-feira, meaning “fourth day”, while in Greek the word is Tetarti meaning simply “fourth”. Similarly, Arabic أربعاء means “fourth”, Hebrew רביעי means “fourth”, and Persian چهارشنبه means “fourth day”. Yet the name for the day in Estonian kolmapäev, Lithuanian trečiadienis, and Latvian trešdiena means “third day” while in Mandarin Chinese xīngqīsān, means “day three”, as Sunday is unnumbered.

Water

Water comes from the Old English wæter, from Proto-Germanic *watar (cognates: Old Saxon watar, Old Frisian wetir, Dutch water, Old High German wazzar, German Wasser, Old Norse vatn, Gothic wato “water”), from PIE *wod-or, from root *wed- (1) “water, wet” (cognates: Hittite watar, Sanskrit udrah, Greek hydor, Old Church Slavonic and Russian voda, Lithuanian vanduo, Old Prussian wundan, Gaelic uisge “water;” Latin unda “wave”).

Linguists believe PIE had two root words for water: *ap- and *wed-. The first (preserved in Sanskrit apah as well as Punjab and julep) was “animate,” referring to water as a living force; the latter referred to it as an inanimate substance. The same probably was true of fire (n.).

The Old English wæterian means to “moisten, irrigate, supply water to; lead (cattle) to water;” from water (n.1). Meaning “to dilute” is attested from late 14c.; now usually as water down (1850). To make water “urinate” is recorded from early 15c.

Water (n.2) is to measure of quality of a diamond, c. 1600, from water (n.1), perhaps as a translation of Arabic ma’ “water,” which also is used in the sense “lustre, splendor.”

Ap

Ap (áp-) is the Vedic Sanskrit term for “water”, which in Classical Sanskrit only occurs in the plural, āpas (sometimes re-analysed as a thematic singular, āpa-), whence Hindi āp. The term is from PIE hxap “water”.

The Indo-Iranian word also survives as the Persian word for water, āb, e.g. in Punjab (from panj-āb “five waters”). In archaic ablauting contractions, the laryngeal of the PIE root remains visible in Vedic Sanskrit, e.g. pratīpa- “against the current”, from *proti-hxp-o-.

In the Rigveda, several hymns are dedicated to “the waters” (āpas): 7.49, 10.9, 10.30, 10.47. In the oldest of these, 7.49, the waters are connected with the drought of Indra.

Agni, the god of fire, has a close association with water and is often referred to as Apām Napāt “offspring of the waters”. The female deity Apah is the presiding deity of Purva Ashadha (The former invincible one) asterism in Vedic astrology

In Hindu philosophy, the term refers to water as an element, one of the Panchamahabhuta, or “five great elements”. In Hinduism, it is also the name of the deva Varuna a personification of water, one of the Vasus in most later Puranic lists.

Abzu

The Abzu (Cuneiform: ZU.AB; Sumerian: abzu; Akkadian: apsû) also called engur, (Cuneiform: LAGAB×HAL; Sumerian: engur; Akkadian: engurru) literally, ab=’ocean’ zu=’deep’ was the name for the primeval sea below the void space of the underworld (Kur) and the earth (Ma) above.

It may also refer to fresh water from underground aquifers that were given a religious fertilizing quality. Lakes, springs, rivers, wells, and other sources of fresh water were thought to draw their water from the abzu.

In the city of Eridu, Enki’s temple was known as E2-abzu (house of the cosmic waters) and was located at the edge of a swamp, an abzu. Certain tanks of holy water in Babylonian and Assyrian temple courtyards were also called abzu (apsû). Typical in religious washing, these tanks were similar to Judaism’s mikvot, the washing pools of Islamic mosques, or the baptismal font in Christian churches.

The Sumerian god Enki (Ea in the Akkadian language) was believed to have lived in the abzu since before human beings were created. His wife Damgalnuna, his mother Nammu, his advisor Isimud and a variety of subservient creatures, such as the gatekeeper Lahmu, also lived in the abzu.

Abzu (apsû) is depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Elish, taken from the library of Assurbanipal (c 630 BCE) but which is about 500 years older. In this story, he was a primal being made of fresh water and a lover to another primal deity, Tiamat, who was a creature of salt water. The Enuma Elish begins:

When above the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, the first, the begetter, and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, she who bore them all; they were still mixing their waters, and no pasture land had yet been formed, nor even a reed marsh…

This resulted in the birth of the younger gods, who latter murder Apsu in order to usurp his lordship of the universe. Enraged, Tiamat gives birth to the first dragons, filling their bodies with “venom instead of blood”, and made war upon her treacherous children, only to be slain by Marduk, the god of Storms, who then forms the heavens and earth from her corpse.

Mercur/Hermes

Mercury is a major Roman god, being one of the Dii Consentes within the ancient Roman pantheon. He is the patron god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence (and thus poetry), messages/communication (including divination), travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves; he is also the guide of souls to the underworld.

He was considered the son of Maia, one of the Pleiades and the mother of Hermes, and Jupiter or Jove, the king of the gods and the god of sky and thunder in Ancient Roman religion and mythology.

Maia is the daughter of Atlas and Pleione the Oceanid, and is the eldest of the seven Pleiades. According to the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, Zeus in the dead of night secretly begot Hermes upon Maia, who avoided the company of the gods, in a cave of Cyllene.

His name is possibly related to the Latin word merx (“merchandise”; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages); another possible connection is the Proto-Indo-European root merĝ- for “boundary, border” (cf. Old English “mearc”, Old Norse “mark” and Latin “margō”) and Greek as the “keeper of boundaries,” referring to his role as bridge between the upper and lower worlds.

From the beginning, Mercury had essentially the same aspects as Hermes, wearing winged shoes (talaria) and a winged hat (petasos), and carrying the caduceus, a herald’s staff with two entwined snakes that was Apollo’s gift to Hermes. He was often accompanied by a cockerel, herald of the new day, a ram or goat, symbolizing fertility, and a tortoise, referring to Mercury’s legendary invention of the lyre from a tortoise shell.

Like Hermes, he was also a god of messages, eloquence and of trade, particularly of the grain trade. Mercury was also considered a god of abundance and commercial success, particularly in Gaul, where he was said to have been particularly revered. He was also, like Hermes, the Romans’ psychopomp, leading newly deceased souls to the afterlife. Additionally, Ovid wrote that Mercury carried Morpheus’ dreams from the valley of Somnus to sleeping humans.

In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, both of which share characteristics with the Greek god Hermes. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome.

In Ovid’s Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld. Mercury, however, fell in love with Larunda and made love to her on the way. Larunda thereby became mother to two children, referred to as the Lares, invisible household gods.

Mercury has influenced the name of many things in a variety of scientific fields, such as the planet Mercury, and the element mercury. The word mercurial is commonly used to refer to something or someone erratic, volatile or unstable, derived from Mercury’s swift flights from place to place. He is often depicted holding the caduceus in his left hand.

When they described the gods of Celtic and Germanic tribes, rather than considering them separate deities, the Romans interpreted them as local manifestations or aspects of their own gods, a cultural trait called the interpretatio Romana.

Mercury in particular was reported as becoming extremely popular among the nations the Roman Empire conquered; Julius Caesar wrote of Mercury being the most popular god in Britain and Gaul, regarded as the inventor of all the arts.

This is probably because in the Roman syncretism, Mercury was equated with the Celtic god Lugus, and in this aspect was commonly accompanied by the Celtic goddess Rosmerta. Although Lugus may originally have been a deity of light or the sun (though this is disputed), similar to the Roman Apollo, his importance as a god of trade made him more comparable to Mercury, and Apollo was instead equated with the Celtic deity Belenus.

Romans associated Mercury with the Germanic god Wotan, by interpretatio Romana; 1st-century Roman writer Tacitus identifies him as the chief god of the Germanic peoples.

In Celtic areas, Mercury was sometimes portrayed with three heads or faces, and at Tongeren, Belgium, a statuette of Mercury with three phalli was found, with the extra two protruding from his head and replacing his nose; this was probably because the number 3 was considered magical, making such statues good luck and fertility charms. The Romans also made widespread use of small statues of Mercury, probably drawing from the ancient Greek tradition of hermae markers.

Hermes is an Olympian god in Greek religion and mythology, son of Zeus and the Pleiad Maia. He is second youngest of the Olympian gods. He is a god of transitions and boundaries. He is quick and cunning, and moves freely between the worlds of the mortal and divine, as emissary and messenger of the gods, intercessor between mortals and the divine, and conductor of souls into the afterlife.

He is protector and patron of herdsmen, thieves, orators and wit, literature and poets, athletics and sports, invention and trade, roads, boundaries and protector of travellers. In some myths he is a trickster, and outwits other gods for his own satisfaction or the sake of humankind. His attributes and symbols include the herma, the rooster and the tortoise, purse or pouch, winged sandals, winged cap, and his main symbol is the herald’s staff, the Greek kerykeion or Latin caduceus which consisted of two snakes wrapped around a winged staff.

In the Roman adaptation of the Greek pantheon (see interpretatio romana), Hermes is identified with the Roman god Mercury, who, though inherited from the Etruscans, developed many similar characteristics, such as being the patron of commerce. It is also suggested that Hermes is cognate of the Vedic Sarama, a mythological being referred to as the dog of the gods, or Deva-shuni.

Sirius

Sirius is the brightest star (in fact, a star system) in the Earth’s night sky. With a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46, it is almost twice as bright as Canopus, the next brightest star.

The most commonly used proper name of this star comes from the Latin Sīrius, from the Ancient Greek Seirios (“glowing” or “scorcher”), although the Greek word itself may have been imported from elsewhere before the Archaic period, one authority suggesting a link with the Egyptian god Osiris. The name’s earliest recorded use dates from the 7th century BC in Hesiod’s poetic work Works and Days.

Sirius is also known colloquially as the “Dog Star”, reflecting its prominence in its constellation, Canis Major (Greater Dog). The heliacal rising of Sirius marked the flooding of the Nile in Ancient Egypt and the “dog days” of summer for the ancient Greeks, while to the Polynesians in the southern hemisphere it marked winter and was an important star for navigation around the Pacific Ocean.

Sirius has over 50 other designations and names attached to it. In Geoffrey Chaucer’s essay Treatise on the Astrolabe, it bears the name Alhabor, and is depicted by a hound’s head. This name is widely used on medieval astrolabes from Western Europe.

In Sanskrit it is known as Mrgavyadha “deer hunter”, or Lubdhaka “hunter”. As Mrgavyadha, the star represents Rudra (Shiva). The star is referred as Makarajyoti in Malayalam and has religious significance to the pilgrim center Sabarimala.

In Scandinavia, the star has been known as Lokabrenna (“burning done by Loki”, or “Loki’s torch”). In the astrology of the Middle Ages, Sirius was a Behenian fixed star, associated with beryl and juniper. Its astrological symbol was listed by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

Many cultures have historically attached special significance to Sirius, particularly in relation to dogs. Indeed, it is often colloquially called the “Dog Star” as the brightest star of Canis Major, the “Great Dog” constellation.

It was classically depicted as Orion’s dog. The Ancient Greeks thought that Sirius’s emanations could affect dogs adversely, making them behave abnormally during the “dog days,” the hottest days of the summer. The Romans knew these days as dies caniculares, and the star Sirius was called Canicula, “little dog.”

The excessive panting of dogs in hot weather was thought to place them at risk of desiccation and disease. In extreme cases, a foaming dog might have rabies, which could infect and kill humans whom they had bitten.

In Iranian mythology, especially in Persian mythology and in Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Persia, Sirius appears as Tishtrya and is revered as the rain-maker divinity (Tishtar of New Persian poetry).

Beside passages in the sacred texts of the Avesta, the Avestan language Tishtrya followed by the version Tir in Middle and New Persian is also depicted in the Persian epic Shahnameh of Ferdowsi.

Due to the concept of the yazatas, powers which are “worthy of worship”, Tishtrya is a divinity of rain and fertility and an antagonist of apaosha, the demon of drought. In this struggle, Tishtrya is beautifully depicted as a white horse.

In Chinese astronomy the star is known as the star of the “celestial wolf” (Chinese romanization: Tiānláng; Japanese romanization: Tenrō) in the Mansion of Jǐng, the well mansion.

Farther afield, many nations among the indigenous peoples of North America also associated Sirius with canines; the Seri and Tohono O’odham of the southwest note the star as a dog that follows mountain sheep, while the Blackfoot called it “Dog-face”. The Cherokee paired Sirius with Antares as a dog-star guardian of either end of the “Path of Souls”. The Pawnee of Nebraska had several associations; the Wolf (Skidi) tribe knew it as the “Wolf Star”, while other branches knew it as the “Coyote Star”. Further north, the Alaskan Inuit of the Bering Strait called it “Moon Dog”.

Several cultures also associated the star with a bow and arrows. The Ancient Chinese visualized a large bow and arrow across the southern sky, formed by the constellations of Puppis and Canis Major. In this, the arrow tip is pointed at the wolf Sirius. A similar association is depicted at the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, where the goddess Satet has drawn her arrow at Hathor (Sirius). Known as “Tir”, the star was portrayed as the arrow itself in later Persian culture.

Sirius is mentioned in Surah, An-Najm (“The Star”), of the Qur’an, where it is given the name aš-ši‘rā or ash-shira; the leader. The verse is: “That He is the Lord of Sirius (the Mighty Star).” (An-Najm:49) Ibn Kathir said in his commentary “Ibn ‘Abbas, Mujahid, Qatada and Ibn Zayd said about Ash-Shi`ra that it is the bright star, named Mirzam Al-Jawza’ (Sirius), which a group of Arabs used to worship.” The alternate name Aschere, used by Johann Bayer, is derived from this.

In Theosophy, it is believed the Seven Stars of the Pleiades transmit the spiritual energy of the Seven Rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius. From there is it sent via the Sun to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays to the human race.

Enki

He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians. A large number of myths about Enki have been collected from many sites, stretching from Southern Iraq to the Levantine coast. He figures in the earliest extant cuneiform inscriptions throughout the region and was prominent from the third millennium down to Hellenistic times.

He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40,” occasionally referred to as his “sacred number.”

The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki. He was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, sometimes confused with the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He was accompanied by an attendant Isimud. He was also associated with the planet Mercury in the Sumerian astrological system.

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

The main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root *hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water.” In Sumerian E-A means “the house of water”, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water'”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

Eridu/Nunki

Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI (“the Mighty Place”); Sumerian: eridu; Akkadian: irîtu modern Arabic: Tell Abu Shahrain) is an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia (modern Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq).

Eridu appears to be the earliest settlement in the region, founded ca. 5400 BC, close to the Persian Gulf near the mouth of the Euphrates River. Because of accumulation of silt at the shoreline over the millennia, the remains of Eridu are now some distance from the gulf at Abu Shahrain in Iraq. Excavation has shown that the city was originally founded on a virgin sand-dune site with no previous occupation.

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu was originally the home of Enki, later known by the Akkadians as Ea, who was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem.

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu was the home of the Abzu temple of the god Enki, the Sumerian counterpart of the Akkadian water-god Ea. Like all the Sumerian and Babylonian gods, Enki/Ea began as a local god, who came to share, according to the later cosmology, with Anu and Enlil, the rule of the cosmos. His kingdom was the sweet waters that lay below earth (Sumerian ab=water; zu=far).

The urban nucleus of Eridu was Enki’s temple, called House of the Aquifer (Cuneiform: E.ZU.AB; Sumerian: e-abzu; Akkadian: bītu apsû), which in later history was called House of the Waters (Cuneiform: E.LAGAB×HAL; Sumerian: e-engur; Akkadian: bītu engurru). The name refers to Enki’s realm. His consort Ninhursanga had a nearby temple at Ubaid.

During the Ur III period a ziggurat was built over the remains of previous temples by Ur-Nammu. Aside from Enmerkar of Uruk (as mentioned in the Aratta epics), several later historical Sumerian kings are said in inscriptions found here to have worked on or renewed the e-abzu temple, including Elili of Ur; Ur-Nammu, Shulgi and Amar-Sin of Ur-III, and Nur-Adad of Larsa.

The Egyptologist David Rohl has conjectured that Eridu, to the south of Ur, was the original Babel and site of the Tower of Babel, rather than the later city of Babylon, for several reasons. Other scholars have discussed at length a number of additional correspondences between the names of “Babylon” and “Eridu”.

Historical tablets state that Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2300 BC) dug up the original “Babylon” and rebuilt it near Akkad, though some scholars suspect this may in fact refer to the much later Assyrian king Sargon II.

Ubaid

The Ubaid period (ca. 6500 to 3800 BCE) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BCE when it is replaced by the Uruk period.

Ubaid 1, sometimes called Eridu (5300–4700 BCE), a phase limited to the extreme south of Iraq, on what was then the shores of the Persian Gulf. This phase, showing clear connection to the Samarra culture to the north, saw the establishment of the first permanent settlement south of the 5 inch rainfall isohyet. These people pioneered the growing of grains in the extreme conditions of aridity, thanks to the high water tables of Southern Iraq.

According to Gwendolyn Leick, Eridu was formed at the confluence of three separate ecosystems, supporting three distinct lifestyles, that came to an agreement about access to fresh water in a desert environment.

The oldest agrarian settlement seems to have been based upon intensive subsistence irrigation agriculture derived from the Samarra culture to the north, characterised by the building of canals, and mud-brick buildings.

The fisher-hunter cultures of the Arabian littoral were responsible for the extensive middens along the Arabian shoreline, and may have been the original Sumerians. They seem to have dwelt in reed huts.

The third culture that contributed to the building of Eridu was the nomadic Semitic pastoralists of herds of sheep and goats living in tents in semi-desert areas.

All three cultures seem implicated in the earliest levels of the city. The urban settlement was centered on an impressive temple complex built of mudbrick, within a small depression that allowed water to accumulate.

The Ubaid period as a whole, based upon the analysis of grave goods, was one of increasingly polarised social stratification and decreasing egalitarianism. Bogucki describes this as a phase of “Trans-egalitarian” competitive households, in which some fall behind as a result of downward social mobility.

Morton Fried and Elman Service have hypothesised that Ubaid culture saw the rise of an elite class of hereditary chieftains, perhaps heads of kin groups linked in some way to the administration of the temple shrines and their granaries, responsible for mediating intra-group conflict and maintaining social order.

It would seem that various collective methods, perhaps instances of what Thorkild Jacobsen called primitive democracy, in which disputes were previously resolved through a council of one’s peers, were no longer sufficient for the needs of the local community.

Ubaid culture originated in the south, but still has clear connections to earlier cultures in the region of middle Iraq. The appearance of the Ubaid folk has sometimes been linked to the so-called Sumerian problem, related to the origins of Sumerian civilisation.

Whatever the ethnic origins of this group, this culture saw for the first time a clear tripartite social division between intensive subsistence peasant farmers, with crops and animals coming from the north, tent-dwelling nomadic pastoralists, dependent upon their herds, and hunter-fisher folk of the Arabian littoral, living in reed huts.

Stein and Özbal describe the Near East oikumene that resulted from Ubaid expansion, contrasting it to the colonial expansionism of the later Uruk period. “A contextual analysis comparing different regions shows that the Ubaid expansion took place largely through the peaceful spread of an ideology, leading to the formation of numerous new indigenous identities that appropriated and transformed superficial elements of Ubaid material culture into locally distinct expressions”.

The archaeological record shows that Arabian Bifacial/Ubaid period came to an abrupt end in eastern Arabia and the Oman peninsula at 3800 BCE, just after the phase of lake lowering and onset of dune reactivation.

At this time, increased aridity led to an end in semi-desert nomadism, and there is no evidence of human presence in the area for approximately 1000 years, the so-called “Dark Millennium”. This might be due to the 5.9 kiloyear event at the end of the Older Peron.

In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BCE. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

Tell Leilan

The Leyla-Tepe culture is a culture of archaeological interest from the Chalcolithic era. Its population was distributed on the southern slopes of the Central Caucasus (modern Azerbaijan, Agdam District), from 4350 until 4000 BC.

The Leyla-Tepe culture includes a settlement in the lower layer of the settlements Poilu I, Poilu II, Boyuk-Kesik I and Boyuk-Kesik II. They apparently buried their dead in ceramic vessels. Similar amphora burials in the South Caucasus are found in the Western Georgian Jar-Burial Culture.

The culture has also been linked to the north Ubaid period monuments, in particular, with the settlements in the Eastern Anatolia Region (Arslan-tepe, Coruchu-tepe, Tepechik, etc.).

An expedition to Syria by the Russian Academy of Sciences revealed the similarity of the Maykop and Leyla-Tepe artifacts with those found recently while excavating the ancient city of Tel Khazneh I, from the 4th millennium BC.

The settlement is of a typical Western-Asian variety, with the dwellings packed closely together and made of mud bricks with smoke outlets. It has been suggested that the Leyla-Tepe were the founders of the Maykop culture (ca. 3700 BC—3000 BC), a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia.

In the south it borders the approximately contemporaneous Kura-Araxes culture (3500—2200 BC), which extends into eastern Anatolia and apparently influenced it. To the north is the Yamna culture, including the Novotitorovka culture (3300—2700), which it overlaps in territorial extent. It is contemporaneous with the late Uruk period in Mesopotamia.

The Kuban River is navigable for much of its length and provides an easy water-passage via the Sea of Azov to the territory of the Yamna culture, along the Don and Donets River systems. The Maykop culture was thus well-situated to exploit the trading possibilities with the central Ukraine area.

New data revealed the similarity of artifacts from the Maykop culture with those found recently in the course of excavations of the ancient city of Tell Khazneh in northern Syria, the construction of which dates back to 4000 BC. Radiocarbon dates for various monuments of the Maykop culture are from 3950 – 3650 – 3610 – 2980 calBC.

It has been suggested that the Leyla-Tepe were the founders of the Maykop culture. An expedition to Syria by the Russian Academy of Sciences revealed the similarity of the Maykop and Leyla-Tepe artifacts with those found recently while excavating the ancient city of Tel Khazneh I, from the 4th millennium BC.

In 2010, nearly 200 Bronze Age sites were reported stretching over 60 miles between the Kuban and Nalchik rivers, at an altitude of between 4,620 feet and 7,920 feet. They were all “visibly constructed according to the same architectural plan, with an oval courtyard in the center, and connected by roads.”

Its inhumation practices were characteristically Indo-European, typically in a pit, sometimes stone-lined, topped with a kurgan (or tumulus). Stone cairns replace kurgans in later interments. The Maykop kurgan was extremely rich in gold and silver artifacts; unusual for the time.

Gamkrelidze and Ivanov suggest that the Maykop culture (or its ancestor) may have been a way-station for Indo-Europeans migrating from the South Caucasus and/or eastern Anatolia to a secondary Urheimat on the steppe. This would essentially place the Anatolian stock in Anatolia from the beginning.

Considering that some attempt has been made to unite Indo-European with the Northwest Caucasian languages, an earlier Caucasian pre-Urheimat is not out of the question. However, most linguists and archaeologists consider this hypothesis incorrect, and prefer the Eurasian steppes as the genuine IE Urheimat.8

The Armenian hypothesis of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat, based on the Glottalic theory, suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 4th millennium BC in the Armenian Highland.

It is an Indo-Hittite model and does not include the Anatolian languages in its scenario. The phonological peculiarities proposed in the Glottalic theory would be best preserved in the Armenian language and the Germanic languages, the former assuming the role of the dialect which remained in situ, implied to be particularly archaic in spite of its late attestation.

The Proto-Greek language would be practically equivalent to Mycenaean Greek and date to the 17th century BC, closely associating Greek migration to Greece with the Indo-Aryan migration to India at about the same time (viz., Indo-European expansion at the transition to the Late Bronze Age, including the possibility of Indo-European Kassites).

The Armenian hypothesis was proposed by Russian linguists T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov in 1985, presenting it first in two articles in Vestnik drevnej istorii and then in a much larger work. Gamkrelidze and Ivanov argue that IE spread out from Armenia into the Pontic steppe, from which it expanded – as per the Kurgan hypothesis – into Western Europe. The Hittite, Indo-Iranian, Greek and Armenian branches split from the Armenian homeland.

The Armenian hypothesis argues for the latest possible date of Proto-Indo-European (sans Anatolian), roughly a millennium later than the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis. In this, it figures as an opposite to the Anatolian hypothesis, in spite of the geographical proximity of the respective suggested Urheimaten, diverging from the timeframe suggested there by as much as three millennia.

Robert Drews, commenting on the hypothesis, says that “most of the chronological and historical arguments seem fragile at best, and of those that I am able to judge, some are evidently wrong”.

However, he argues that it is far more powerful as a linguistic model, providing insights into the relationship between Indo-European and the Semitic and Kartvelian languages.

He continues to say “It is certain that the inhabitants of the forested areas of Armenia very early became accomplished woodworkers, and it now appears that in the second millennium they produced spoked-wheel vehicles that served as models as far away as China. And we have long known that from the second millennium onward, Armenia was important for the breeding of horses. It is thus not surprising to find that what clues we have suggest that chariot warfare was pioneered in eastern Anatolia. Finally, our picture of what the PIE speakers did, and when, owes much to the recently proposed hypothesis that the homeland of the PIE speakers was Armenia.”

I. Grepin, reviewing Gamkrelidze and Ivanov’s book, wrote that their model of linguistic relationships is “the most complex, far reaching and fully supported of this century.”

Graeco-Aryan (or Graeco-Armeno-Aryan) is a hypothetical clade within the Indo-European family, ancestral to the Greek language, the Armenian language, and the Indo-Iranian languages. Graeco-Aryan unity would have become divided into Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian by the mid 3rd millennium BC.

Conceivably, Proto-Armenian would have been located between Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian, consistent with the fact that Armenian shares certain features only with Indo-Iranian (the satem change) but others only with Greek (s > h).

Graeco-Aryan has comparatively wide support among Indo-Europeanists for the Indo-European Homeland to be located in the Armenian Highland. Early and strong evidence was given by Euler’s 1979 examination on shared features in Greek and Sanskrit nominal flection.

Used in tandem with the Graeco-Armenian hypothesis, the Armenian language would also be included under the label Aryano-Greco-Armenic, splitting into proto-Greek/Phrygian and “Armeno-Aryan” (ancestor of Armenian and Indo-Iranian).

In the context of the Kurgan hypothesis, Greco-Aryan is also known as “Late PIE” or “Late Indo-European” (LIE), suggesting that Greco-Aryan forms a dialect group which corresponds to the latest stage of linguistic unity in the Indo-European homeland in the early part of the 3rd millennium BC. By 2500 BC, Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian had separated, moving westward and eastward from the Pontic Steppe, respectively.

If Graeco-Aryan is a valid group, Grassmann’s law may have a common origin in Greek and Sanskrit. Note, however, that Grassmann’s law in Greek postdates certain sound changes that happened only in Greek and not Sanskrit, which suggests that it cannot strictly be an inheritance from a common Graeco-Aryan stage. Rather, it is more likely an areal feature that spread across a then-contiguous Graeco-Aryan-speaking area after early Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian had developed into separate dialects but before they ceased being in geographic contact.

Graeco-Aryan is invoked in particular in studies of comparative mythology, e.g. by West (1999) and Watkins (2001).

The Kura–Araxes culture or the early trans-Caucasian culture was a civilization that existed from 3400 BC until about 2000 BC, which has traditionally been regarded as the date of its end, but it may have disappeared as early as 2600 or 2700 BC.

There is evidence of trade with Mesopotamia, as well as Asia Minor. It is, however, considered above all to be indigenous to the Caucasus, and its major variants characterized (according to Caucasus historian Amjad Jaimoukha) later major cultures in the region.

The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; thence it spread northward in Caucasus by 3000 BC (but never reaching Colchis), and during the next millennium it proceeded westward to the Erzurum plain, southwest to Cilicia, and to the southeast into an area below the Urmia basin and Lake Van, and finally down to the borders of present-day Syria.

Altogether, the early Trans-Caucasian culture, at its greatest spread, enveloped a vast area approximately 1,000 km by 500 km, and mostly encompassed, on modern-day territories, the Southern Caucasus (except western Georgia), Northwestern Iran, the Northeastern Caucasus, and Eastern Turkey.

The name of the culture is derived from the Kura and Araxes river valleys. Its territory corresponds to parts of modern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Dagestan, Georgia, Ingushetia, Iran, North Ossetia, and Turkey. It may have given rise to the later Khirbet Kerak ware culture found in Syria and Canaan after the fall of the Akkadian Empire.

In the earliest phase of the Kura-Araxes culture, metal was scarce, but the culture would later display “a precocious metallurgical development, which strongly influenced surrounding regions”. They worked copper, arsenic, silver, gold, tin, and bronze. Their metal goods were widely distributed, from the Volga, Dnieper and Don-Donets river systems in the north to Syria and Palestine in the south and Anatolia in the west.

Their pottery was distinctive; in fact, the spread of their pottery along trade routes into surrounding cultures was much more impressive than any of their achievements domestically. It was painted black and red, using geometric designs for ornamentation. Examples have been found as far south as Syria and Israel, and as far north as Dagestan and Chechnya.

The spread of this pottery, along with archaeological evidence of invasions, suggests that the Kura-Araxes people may have spread outward from their original homes, and most certainly, had extensive trade contacts. Jaimoukha believes that its southern expanse is attributable primarily to Mitanni and the Hurrians.

They are also remarkable for the production of wheeled vehicles (wagons and carts), which were sometimes included in burial kurgans. Inhumation practices are mixed. Flat graves are found, but so are substantial kurgan burials, the latter of which may be surrounded by cromlechs.

This points to a heterogeneous ethno-linguistic population. Hurrian and Urartian elements are quite probable, as are Northeast Caucasian ones. Some authors subsume Hurrians and Urartians under Northeast Caucasian as well as part of the Alarodian theory.

The presence of Kartvelian languages was also highly probable. Influences of Semitic languages and Indo-European languages are also highly possible, though the presence of the languages on the lands of the Kura–Araxes culture is more controversial.

Late in the history of this culture, its people built kurgans of greatly varying sizes, containing greatly varying amounts and types of metalwork, with larger, wealthier kurgans surrounded by smaller kurgans containing less wealth. This trend suggests the eventual emergence of a marked social hierarchy. Their practice of storing relatively great wealth in burial kurgans was probably a cultural influence from the more ancient civilizations of the Fertile Crescent to the south.

The Khabur or Khaboor River is the largest perennial tributary to the Euphrates in Syrian territory. Although the Khabur originates in Turkey, the karstic springs around Ra’s al-‘Ayn are the river’s main source of water.

Several important wadis join the Khabur north of Al-Hasakah, together creating what is known as the Khabur Triangle, or Upper Khabur area. From north to south, annual rainfall in the Khabur basin decreases from over 400 mm to less than 200 mm, making the river a vital water source for agriculture throughout history.

Since the 1930s, numerous archaeological excavations and surveys have been carried out in the Khabur Valley, indicating that the region has been occupied since the Lower Palaeolithic period. Important sites that have been excavated include Tell Halaf, Tell Brak, Tell Leilan, Tell Mashnaqa, Tell Mozan and Tell Barri. The region of the Khabur River is also associated with the rise of the Kingdom of the Mitanni that flourished c.1500-1300 BC.

The region has given its name to a distinctive painted ware found in northern Mesopotamia and Syria in the early 2nd millennium BCE, called Khabur ware, a specific type of pottery named after the Khabur River region, in northeastern Syria, where large quantities of it were found by the archaeologist Max Mallowan at the site of Chagar Bazar.

The pottery’s distribution is not confined to the Khabur region, but spreads across northern Iraq and is also found at a few sites in Turkey and Iran. The Hurrians were masterful ceramists. Their pottery is commonly found in Mesopotamia and in the lands west of the Euphrates; it was highly valued in distant Egypt, by the time of the New Kingdom.

Archaeologists use the terms Khabur ware and Nuzi ware for two types of wheel-made pottery used by the Hurrians. Khabur ware is characterized by reddish painted lines with a geometric triangular pattern and dots, while Nuzi ware have very distinctive forms, and are painted in brown or black.

The Hurrians had a reputation in metallurgy. The Sumerians borrowed their copper terminology from the Hurrian vocabulary. Copper was traded south to Mesopotamia from the highlands of Anatolia. The Khabur Valley had a central position in the metal trade, and copper, silver and even tin were accessible from the Hurrian-dominated countries Kizzuwatna and Ishuwa situated in the Anatolian highland.

The name of the country of Ishuwa, which might have had a substantial Hurrian population, meant “horse-land”. Aśvaḥ is the Sanskrit word for a horse, one of the significant animals finding references in the Vedas as well as later Hindu scriptures. The corresponding Avestan term is aspa. The word is cognate to Latin equus, Greek ίππος (hippos), Germanic *ehwaz and Baltic *ašvā all from PIE *hek’wos.

The Trialeti culture, named after Trialeti region of Georgia, is attributed to the first part of the 2nd millennium BC. In the late 3rd millennium BC, settlements of the Kura-Araxes culture began to be replaced by early Trialeti culture sites.

The Trialeti culture was the second culture to appear in Georgia, after the Shulaveri-Shomu culture, a Late Neolithic/Eneolithic culture that existed on the territory of present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Armenian Highlands from 6000 to 4000 BC.

Shulaveri-Shomu culture is thought to be one of the earliest known Neolithic cultures. It predates the Kura-Araxes culture and surrounding areas, and had close relation with the middle Bronze Age culture called Trialeti culture (ca. 3000 – 1500 BC). Sioni culture of Eastern Georgia possibly represents a transition from the Shulaveri to the Kura-Arax cultural complex.

In around ca. 6000–4200 B.C the Shulaveri-Shomu and other Neolithic/Chalcolithic cultures of the Southern Caucasus use local obsidian for tools, raise animals such as cattle and pigs, and grow crops, including grapes.

Many of the characteristic traits of the Shulaverian material culture (circular mudbrick architecture, pottery decorated by plastic design, anthropomorphic female figurines, obsidian industry with an emphasis on production of long prismatic blades) are believed to have their origin in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Hassuna, Halaf).

The Trialeti culture shows close ties with the highly developed cultures of the ancient world, particularly with the Aegean, but also with cultures to the south, such as probably the Sumerians and their Akkadian conquerors.

The site at Trialeti was originally excavated in 1936–1940 in advance of a hydroelectric scheme, when forty-six barrows were uncovered. A further six barrows were uncovered in 1959–1962.

The Trialeti culture was known for its particular form of burial. The elite were interred in large, very rich burials under earth and stone mounds, which sometimes contained four-wheeled carts. Also there were many gold objects found in the graves. These gold objects were similar to those found in Iran and Iraq. They also worked tin and arsenic.

This form of burial in a tumulus or “kurgan”, along with wheeled vehicles, is the same as that of the Kurgan culture which has been associated with the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. In fact, the black burnished pottery of especially early Trialeti kurgans is similar to Kura-Araxes pottery.

In a historical context, their impressive accumulation of wealth in burial kurgans, like that of other associated and nearby cultures with similar burial practices, is particularly noteworthy. This practice was probably a result of influence from the older civilizations to the south in the Fertile Crescent.

Nu/Nun

Nu (“watery one”), also called Nun (“inert one”) is the deification of the primordial watery abyss in ancient Egyptian religion. In the Ogdoad cosmogony, the word nu means “abyss”.

The Ancient Egyptians envisaged the oceanic abyss of the Nun as surrounding a bubble in which the sphere of life is encapsulated, representing the deepest mystery of their cosmogony. In Ancient Egyptian creation accounts the original mound of land comes forth from the waters of the Nun.

The Nun is the source of all that appears in a differentiated world, encompassing all aspects of divine and earthly existence. In the Ennead cosmogony Nun is perceived as transcendent at the point of creation alongside Atum the creator god.

Nu was shown usually as male but also had aspects that could be represented as female or male. Nunet (also spelt Naunet) is the female aspect, which is the name Nu with a female gender ending. The male aspect, Nun, is written with a male gender ending. As with the primordial concepts of the Ogdoad, Nu’s male aspect was depicted as a frog, or a frog-headed man. In Ancient Egyptian art, Nun also appears as a bearded man, with blue-green skin, representing water. Naunet is represented as a snake or snake-headed woman.

Beginning with the Middle Kingdom Nun is described as “the Father of the Gods” and he is depicted on temple walls throughout the rest of Ancient Egyptian religious history.

The Ogdoad includes along with Naunet and Nun, Amaunet and Amun, Hauhet and Heh, and Kauket with Kuk. Like the other Ogdoad deities, Nu did not have temples or any center of worship. Even so, Nu was sometimes represented by a sacred lake, or, as at Abydos, by an underground stream.

In the 12th Hour of the Book of Gates Nu is depicted with upraised arms holding a “solar bark” (or barque, a boat). The boat is occupied by eight deities, with the scarab deity Khepri standing in the middle surrounded by the seven other deities.

During the late period when Egypt became occupied, the negative aspect of the Nun (chaos) became the dominant perception, reflecting the forces of disorder that were set loose in the country.

Uruk

Inanna (Sumerian: Inanna; Akkadian: Ištar; Neo-Assyrian: MUŠ) was the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and warfare, and goddess of the E-Anna temple at the city of Uruk, her main centre. Inanna was the most prominent female deity in ancient Mesopotamia. As early as the Uruk period (ca. 4000–3100 BC), Inanna was associated with the city of Uruk.

In his connections with Inanna, Enki shows other aspects of his non-Patriarchal nature. The myth Enki and Inanna tells the story of the young goddess of the É-anna temple of Uruk, who visits the senior god of Eridu, and is entertained by him in a feast.

The seductive god plies her with beer, and the young goddess maintains her virtue, whilst Enki proceeds to get drunk. In generosity he gives her all the gifts of his Me, the gifts of civilized life.

Next morning, with a hangover, he asks his servant Isimud for his Me, only to be informed that he has given them to Inanna. Upset at his actions, he sends Galla demons to recover them. Inanna escapes her pursuers and arrives safely back at the quay at Uruk. Enki realises that he has been tricked in his hubris and accepts a peace treaty forever with Uruk.

Politically, this myth would seem to indicate events of an early period when political authority passed from Enki’s city of Eridu to Inanna’s city of Uruk.

Inanna’s name derives from Lady of Heaven (Sumerian: nin-an-ak). The cuneiform sign of Inanna; however, is not a ligature of the signs lady (Sumerian: nin; Cuneiform: SAL.TUG) and sky (Sumerian: an; Cuneiform: AN).

These difficulties have led some early Assyriologists to suggest that originally Inanna may have been a Proto-Euphratean goddess, possibly related to the Hurrian mother goddess Hannahannah, accepted only latterly into the Sumerian pantheon, an idea supported by her youthfulness, and that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, at first she had no sphere of responsibilities.

The view that there was a Proto-Euphratean substrate language in Southern Iraq before Sumerian is not widely accepted by modern Assyriologists.

Inara, in Hittite–Hurrian mythology, was the goddess of the wild animals of the steppe and daughter of the Storm-god Teshub/Tarhunt. She corresponds to the “potnia theron” of Greek mythology, better known as Artemis. Inara’s mother is probably Hebat and her brother is Sarruma.

The mother goddess Hannahannah promises Inara land and a man during a consultation by Inara. Inara then disappears. Her father looks for her, joined by Hannahannah with a bee. The story resembles that of Demeter and her daughter Persephone, in Greek myth.

Hannahannah (from Hittite hanna- “grandmother”) is a Hurrian Mother Goddess related to or influenced by the pre-Sumerian goddess Inanna. Hannahannah was also identified with the Hurrian goddess Hebat. Christopher Siren reports that Hannahannah is associated with the Gulses. In Hurrian mythology, the Hutena are goddesses of fate. They are similar to the Norns of Norse mythology or the Moirai of ancient Greece.

Inanna has a central role in the myth of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. A major theme in the narrative is the rivalry between the rulers of Aratta and Uruk for the heart of Inanna. Ultimately, this rivalry results in natural resources coming to Uruk and the invention of writing. The text describes a tension between the cities:

The lord of Aratta placed on his head the golden crown for Inana. But he did not please her like the lord of Kulaba (A district in Uruk). Aratta did not build for holy Inana (sic.; Alternate spelling of ‘Inanna’) — unlike the Shrine E-ana (Temple in Uruk for Inanna).

Aratta is a land that appears in Sumerian myths surrounding Enmerkar and Lugalbanda, two early and possibly mythical kings of Uruk also mentioned on the Sumerian king list. It is structured as a mirror image of Uruk, only Aratta has natural resources (i.e. gold, silver, lapis lazuli) that Uruk needs.

It is described in Sumerian literature as a fabulously wealthy place full of gold, silver, lapis lazuli and other precious materials, as well as the artisans to craft them. It is remote and difficult to reach. It is home to the goddess Inanna, who transfers her allegiance from Aratta to Uruk. It is conquered by Enmerkar of Uruk.

In the Sumerian epic entitled Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, in a speech of Enmerkar, an incantation is pronounced that has a mythical introduction. Kramer’s translation is as follows:

Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion,

There was no hyena, there was no lion,

There was no wild dog, no wolf,

There was no fear, no terror,

Man had no rival.

In those days, the lands of Subur (and) Hamazi,

Harmony-tongued Sumer, the great land of the decrees of princeship,

Uri, the land having all that is appropriate,

The land Martu, resting in security,

The whole universe, the people in unison

To Enlil in one tongue [spoke].

(Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy,

The lord of wisdom, who understands the land,

The leader of the gods,

Endowed with wisdom, the lord of Eridu

Changed the speech in their mouths, [brought] contention into it,

Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one.

The term “Sumerian” is the common name given to the ancient non-Semitic inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Sumer, by the Semitic Akkadians. The Sumerians referred to themselves as ùĝ saĝ gíg-ga, phonetically uŋ saŋ giga, literally meaning “the black-headed people”, and to their land as ki-en-gi(-r) (‘place’ + ‘lords’ + ‘noble’), meaning “place of the noble lords”.

The Akkadian word Shumer may represent the geographical name in dialect, but the phonological development leading to the Akkadian term šumerû is uncertain. Hebrew Shinar, Egyptian Sngr, and Hittite Šanhar(a), all referring to southern Mesopotamia, could be western variants of Shumer.

Shinar (Septuagint Sennaar) is a biblical geographical locale of uncertain boundaries in Mesopotamia. The name may be a corruption of Hebrew Shene neharot (“two rivers”), Hebrew Shene arim (“two cities”), or Akkadian Shumeru.

The name Shinar occurs eight times in the Hebrew Bible, in which it refers to Babylonia. This location of Shinar is evident from its description as encompassing both Babel (Babylon) (in northern Babylonia) and Erech (Uruk) (in southern Babylonia).

In the Book of Genesis 10:10, the beginning of Nimrod’s kingdom is said to have been “Babel [Babylon], and Erech [Uruk], and Akkad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.”

Verse 11:2 states that Shinar enclosed the plain that became the site of the Tower of Babel after the Great Flood. After the Flood, the sons of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, had stayed first in the highlands of Armenia, and then migrated to Shinar.

In Genesis 14:1,9, King Amraphel rules Shinar. Shinar is further mentioned in Joshua 7:21; Isaiah 11:11; Daniel 1:2; and Zechariah 5:11, as a general synonym for Babylonia.

Urartu, corresponding to the biblical Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili) was an Iron Age kingdom centered on Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands.

Strictly speaking, Urartu is the Assyrian term for a geographical region, while “kingdom of Urartu” or “Biainili lands” are terms used in modern historiography for the Urartian-speaking Iron Age state that arose in that region. This language appears in inscriptions.

Though there is no written evidence of any other language being spoken in this kingdom, it is argued on linguistic evidence that Proto-Armenian came in contact with Urartian at an early date.

That a distinction should be made between the geographical and the political entity was already pointed out by König (1955). The landscape corresponds to the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, the Iranian Plateau, and the Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highlands.

The kingdom rose to power in the mid-9th century BC, but was conquered by Media in the early 6th century BC. The heirs of Urartu are the Armenians and their successive kingdoms.

Scholars believe that Urartu is an Akkadian variation of Ararat of the Old Testament. Indeed, Mount Ararat is located in ancient Urartian territory, approximately 120 km north of its former capital.

Armani-Subartu (Akkadian Šubartum/Subartum/ina Šú-ba-ri, Assyrian mât Šubarri) or Arme-Shupria (Sumerian Su-bir/Subar/Šubur) was a Proto-Armenian Hurrian-speaking kingdom mentioned in Bronze Age literature, located in the Armenian Highland, to the southwest of Lake Van, bordering on Ararat proper. Scholars have linked the district in the area called Arme or Armani, to the name Armenia. Shubria was part of the Urartu confederation.

Subartu was apparently a polity in Northern Mesopotamia, at the upper Tigris. Some scholars suggest that Subartu is an early name for Assyria proper on the Tigris and westward, although there are various other theories placing it sometimes a little farther to the east and/or north.

Its precise location has not been identified. From the point of view of the Akkadian Empire, Subartu marked the northern geographical horizon, just as Martu, Elam and Sumer marked “west”, “east” and “south”, respectively.

The Sumerian mythological epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta lists the countries where the “languages are confused” as Subartu, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki, and the Martu land. Similarly, the earliest references to the “four quarters” by the kings of Akkad name Subartu as one of these quarters around Akkad, along with Martu, Elam, and Sumer.

Subartu in the earliest texts seem to have been farming mountain dwellers, frequently raided for slaves. Eannatum of Lagash was said to have smitten Subartu or Shubur, and it was listed as a province of the empire of Lugal-Anne-Mundu.

In a later era Sargon of Akkad campaigned against Subar, and his grandson Naram-Sin listed Subar along with Armani among the lands under his control. Ishbi-Erra of Isin and Hammurabi also claimed victories over Subar.

Armani, (also given as Armanum) was an ancient kingdom mentioned by Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin of Akkad as stretching from Ibla to Bit-Nanib, its location is heavily debated, and it continued to be mentioned in the later Assyrian inscriptions.

Armani was mentioned alongside Ibla in the geographical treaties of Sargon, this led some historians to identify Ibla with Syrian Ebla and Armani with Syrian Armi. Prof Michael C. Astour refuse to identify Armani with Armi as Naram-Sin makes it clear that the Ibla he sacked (in c.2240 BC) was a border town of the land of Armani, while the Armi in the Eblaite tablets is a vassal to Ebla.

Armani was attested in the treaties of Sargon in a section that mentions regions located in Assyria and Babylonia or territories adjacent to the East in contrast to the Syrian Ebla location in the west.

The later King Adad-Nirari I of Assyria also mentions Arman as being located east of the Tigris and on the border between Assyria and Babylon, historians who disagree with the identification of Akkadian Armani with Syrian Armi, place it (along with Akkadian Ibla) north of the Hamrin Mountains in northern Iraq.

It has been suggested by early 20th century Armenologists that Old Persian Armina and the Greek Armenoi are continuations of an Assyrian toponym Armânum or Armanî. Another mention by pharaoh Thutmose III of Egypt in the 33rd year of his reign (1446 BC) as the people of Ermenen, and says in their land “heaven rests upon its four pillars”.

Hieros gamos

The cosmogenic myth common in Sumer was that of the hieros gamos, a sacred marriage where divine principles in the form of dualistic opposites came together as male and female to give birth to the cosmos. In the epic Enki and Ninhursag, Enki, as lord of Ab or fresh water (also the Sumerian word for semen), is living with his wife in the paradise of Dilmun.

Despite being a place where “the raven uttered no cries” and “the lion killed not, the wolf snatched not the lamb, unknown was the kid-killing dog, unknown was the grain devouring boar”, Dilmun had no water and Enki heard the cries of its Goddess, Ninsikil, and orders the sun-God Utu to bring fresh water from the Earth for Dilmun.

Dilmun was identified with Bahrein, whose name in Arabic means “two seas”, where the fresh waters of the Arabian aquifer mingle with the salt waters of the Persian Gulf. This mingling of waters was known in Sumerian as Nammu, and was identified as the mother of Enki.

The subsequent tale, with similarities to the Biblical story of the forbidden fruit, repeats the story of how fresh water brings life to a barren land.

Enki, the Water-Lord, seduces and has intercourse different women – incest. He attempts seduction of Uttu (weaver or spider, the weaver of the web of life). Upset about Enki’s reputation, Uttu consults Ninhursag, who, upset at the promiscuous wayward nature of her spouse, advises Uttu to avoid the riverbanks, the places likely to be affected by flooding, the home of Enki.

In another version of this myth Ninhursag, his consort, takes Enki’s semen from Uttu’s womb and plants it in the earth where eight plants rapidly germinate. With his two-faced servant and steward Isimud, Enki, in the swampland, eats it despite warnings. And so, consuming his own semen, he falls pregnant (ill with swellings) in his jaw, his teeth, his mouth, his hip, his throat, his limbs, his side and his rib.

The gods are at a loss to know what to do, chagrinned they “sit in the dust”. As Enki lacks a womb with which to give birth, he seems to be dying with swellings. The fox then asks Enlil King of the Gods, “If i bring Ninhursag before thee, what shall be my reward?” Ninhursag’s sacred fox then fetches the goddess.

Ninhursag relents and takes Enki’s Ab (water, or semen) into her body, and gives birth to gods of healing of each part of the body. Abu for the Jaw, Nintul for the Hip, Ninsutu for the tooth, Ninkasi for the mouth, Dazimua for the side, Enshagag for the Limbs. The last one, Ninti (Lady Rib), is also a pun on Lady Life, a title of Ninhursag herself.

The story thus symbolically reflects the way in which life is brought forth through the addition of water to the land, and once it grows, water is required to bring plants to fruit. It also counsels balance and responsibility, nothing to excess.

Ninti, the title of Ninhursag, also means “the mother of all living”, and was a title given to the later Hurrian goddess Kheba. This is also the title given in the Bible to Eve, the Hebrew and Aramaic Ḥawwah (חוה), who was made from the rib of Adam, in a strange reflection of the Sumerian myth, in which Adam — not Enki — walks in the Garden of Paradise.

In Hurrian mythology, the Hutena are goddesses of fate. They are similar to the Norns of Norse mythology or the Moirai of ancient Greece. They are called the Gul Ses (Gul-Shesh; Gulshesh; Gul-ashshesh) in Hittite mythology.

Hannahannah (from Hittite hanna- “grandmother”) is a Hurrian Mother Goddess related to or influenced by the pre-Sumerian goddess Inanna. Hannahannah was also identified with the Hurrian goddess Hebat. Christopher Siren reports that Hannahannah is associated with the Gulses.

Adapa

Mesopotamian myth tells of seven antediluvian sages, who were sent by Ea, the wise god of Eridu, to bring the arts of civilisation to humankind. The word Abgallu, sage (Ab = water, Gal = great, Lu = man, Sumerian) survived into Nabatean times, around the 1st century, as apkallum, used to describe the profession of a certain kind of priest.

The sages are described in Mesopotamian literature as ‘pure parādu-fish, probably carp, whose bones are found associated with the earliest shrine, and still kept as a holy duty in the precincts of Near Eastern mosques and monasteries.

The pool of the Abzu at the front of his temple was adopted also at the temple to Nanna (Akkadian Sin) the Moon, at Ur, and spread from there throughout the Middle East. It is believed to remain today as the sacred pool at Mosques, or as the holy water font in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.

The first of the Mesopotamian seven sages, Adapa, also known as Uan (Poseidon – Wanax), the name given as Oannes (Johannes) by Berossus, introduced the practice of the correct rites of religious observance as priest of the E’Apsu temple, at Eridu.

Adapa was a mortal man from a godly lineage, a son of Ea (Enki in Sumerian), the god of wisdom and of the ancient city of Eridu, who brought the arts of civilization to that city (from Dilmun, according to some versions). Adapa as a fisherman was iconographically portrayed as a fish-man composite.

Adapa unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BC), in fragmentary tablets from Tell el-Amarna, and from Assur, of the late second millennium BC.

He broke the wings of Ninlil the South Wind, who had overturned his fishing boat, and was called to account before Anu. Ea, his patron god, warned him to apologize humbly for his actions, but not to partake of food or drink while he was in heaven, as it would be the food of death.

Anu, impressed by Adapa’s sincerity, offered instead the food of immortality, but Adapa heeded Ea’s advice, refused, and thus missed the chance for immortality that would have been his.

Vague parallels can be drawn to the story of Genesis, where Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden by Yahweh, after they ate from the Tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thus gaining death.

Parallels are also apparent (to an even greater degree) with the story of Persephone visiting Hades, who was warned to take nothing from that kingdom. Stephanie Dalley writes “From Erra and Ishum we know that all the sages were banished … because they angered the gods, and went back to the Apsu, where Ea lived, and … the story … ended with Adapa’s banishment” p. 182.

Adapa is often identified as advisor to the mythical first (antediluvian) king of Eridu, Alulim, the first king of Eridu, and the first king of Sumer, according to the mythological antediluvian section of the Sumerian King List. Enki, the god of Eridu, is said to have brought civilization to Sumer at this point, or just shortly before.

In a chart of antediluvian generations in Babylonian and Biblical traditions, Professor William Wolfgang Hallo associates Alulim with the composite half-man, half-fish counselor or culture hero (Apkallu) Uanna-Adapa (Oannes), and suggests an equivalence between Alulim and Enosh in the Sethite genealogy given in Genesis chapter 5. Hallo notes that Alulim’s name means “Stag”.

Deer had a central role in the ancient art, culture and mythology of the Hittites, the Ancient Egyptians, the Celts, the ancient Greeks, the Asians and several others. In Japanese Shintoism, the sika deer is believed to be a messenger to the gods. In China deer are associated with great medicinal significance, while spotted deer in particular are believed to accompany the god of longevity

Alalu is god in Hurrian mythology. He is considered to have housed “the Hosts of Sky”, the divine family, because he was a progenitor of the gods, and possibly the father of Earth.

The name “Alalu” was borrowed from Semitic mythology and is a compound word made up of the Semitic definite article al and the Semitic supreme deity Alu. The -u at the end of the word is an inflectional ending; thus, Alalu may also occur as Alali or Alala depending on the position of the word in the sentence. He was identified by the Greeks as Hypsistos. He was also called Alalus.