![]()

This is some of the similarities between Sumerian (Mesopotamian) mythology/religion, comming out of the PIE-culture existing in the Armenian Highland, and Jewish/Christian mythology/religion. But it is just a start cause there is a lot of similarities to be found.

There should be no doubt that Judaism and Christianity have the same root as the other mythologies/religions, as f ex the Greek mythology, Buddhism or Hinduism. In this way Mesopotamian mythology/religion have kept it going until today.

Comperative religion

The Bible was formed over many centuries, by many authors, and reflects shifting patterns of religious belief; consequently, its concepts of cosmology are not always consistent. Nor should the Biblical texts be taken to represent the beliefs of all Jews or Christians at the time they were put into writing.

The majority of those making up Hebrew Bible or Old Testament in particular represent the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community, the members of a late Judean religious tradition centered in Jerusalem and devoted to the exclusive worship of Yahweh.

Biblical cosmology is the biblical writers’ conception of the Cosmos as an organised, structured entity, including its origin, order, meaning and destiny.

The universe of the ancient Israelites was made up of a flat disc-shaped earth floating on water, heaven above, underworld below. Humans inhabited earth during life and the underworld after death, and the underworld was morally neutral; only in Hellenistic times (after c.330 BCE) did Jews begin to adopt the Greek idea that it would be a place of punishment for misdeeds, and that the righteous would enjoy an afterlife in heaven.

In this period too the older three-level cosmology was widely replaced by the Greek concept of a spherical earth suspended in space at the center of a number of concentric heavens.

The opening words of the Genesis creation narrative (Genesis 1:1-26) sum up the authors’ view of how the cosmos originated: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth”; Yahweh, the god of Israel, was solely responsible for creation and had no rivals.

Later Jewish thinkers, adopting ideas from Greek philosophy, concluded that God’s Wisdom, Word and Spirit penetrated all things and gave them unity. Christianity in turn adopted these ideas and identified Jesus with the creative word: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity. It is made up of two parts, roughly equivalent to the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis.

In the first part (Genesis 1:1-2:3) Elohim, the Hebrew generic word for God, creates the heaven and the earth in six days, starting with darkness and light on the first day, and ending with the creation of mankind on the sixth day. God then rests on, blesses and sanctifies the seventh day. In the second part (Genesis 2:4-2:24) God, now referred to by the personal name Yahweh, creates the first man from dust and breathes life into him. God then places him in the Garden of Eden and creates the first woman from his side as a companion.

A common hypothesis among modern scholars is that the first major comprehensive draft of the Pentateuch (the series of five books which begins with Genesis and ends with Deuteronomy) was composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BC (the Jahwist source) and that this was later expanded by other authors (the Priestly source) into a work very like the one we have today. The two sources can be identified in the creation narrative: Genesis 1:1-2:3 is Priestly and Genesis 2:4-2:24 is Jahwistic.

Borrowing themes from Mesopotamian mythology, but adapting them to Israel’s belief in one God, the combined narrative is a critique of the Mesopotamian theology of creation: Genesis affirms monotheism and denies polytheism. Robert Alter described the combined narrative as “compelling in its archetypal character, its adaptation of myth to monotheistic ends”.

Biblical cosmology

Creation myths

Genesis creation narrative

Sumerian creation myth

Biblical cosmology

Babylonian cosmology

Christian mythology

Jewish mythology

Mesopotamian mythology

Babylonian mythology

Panbabylonism

Enûma Eliš

Parallels

The Tree of Knowledge/Life

Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament

Syncretism

The Bible’s similarities with Egyptian, Greek and Babylonian mythology are too close to be a coincidence. The writers weren’t isolated from other cultures and they didn’t get their ideas by sitting on some mountaintop meditating with God; they borrowed ideas from their neighbor’s creation myths. The technical term is called called syncretism.

Comparative mythology provides historical and cross-cultural perspectives for Jewish mythology. Both sources behind the Genesis creation narrative borrowed themes from Mesopotamian mythology, but adapted them to their belief in one God, establishing a monotheistic creation in opposition to the polytheistic creation myth of ancient Israel’s neighbors.

Genesis 1–11 as a whole is imbued with Mesopotamian myths. Genesis 1 bears both striking differences from and striking similarities to Babylon’s national creation myth, the Enuma Elish.

On the side of similarities, both begin from a stage of chaotic waters before anything is created, in both a fixed dome-shaped “firmament” divides these waters from the habitable Earth, and both conclude with the creation of a human called “man” and the building of a temple for the god (in Genesis 1, this temple is the entire cosmos).

On the side of contrasts, Genesis 1 is uncompromisingly monotheistic, it makes no attempt to account for the origins of God, and there is no trace of the resistance to the reduction of chaos to order (Gk. theomachy, lit. “God-fighting”), all of which mark the Mesopotamian creation accounts. It also bears similarities to the Baal Cycle of Israel’s neighbor, Ugarit.

The Enuma Elish has also left traces on Genesis 2. Both begin with a series of statements of what did not exist at the moment when creation began; the Enuma Elish has a spring (in the sea) as the point where creation begins, paralleling the spring (on the land – Genesis 2 is notable for being a “dry” creation story) in Genesis 2:6 that “watered the whole face of the ground”; in both myths, Yahweh/the gods first create a man to serve him/them, then animals and vegetation.

At the same time, and as with Genesis 1, the Jewish version has drastically changed its Babylonian model: Eve, for example, seems to fill the role of a mother goddess when, in Genesis 4:1, she says that she has “created a man with Yahweh”, but she is not a divine being like her Babylonian counterpart.

Genesis 2 has close parallels with a second Mesopotamian myth, the Atra-Hasis epic – parallels that in fact extend throughout Genesis 2–11, from the Creation to the Flood and its aftermath. The two share numerous plot-details (e.g. the divine garden and the role of the first man in the garden, the creation of the man from a mixture of earth and divine substance, the chance of immortality, etc.), and have a similar overall theme: the gradual clarification of man’s relationship with God(s) and animals.

The narratives in Genesis 1–2 were not the only creation myths in ancient Israel, and the complete biblical evidence suggests two contrasting models. The first is the “logos” (meaning speech) model, where a supreme God “speaks” dormant matter into existence. The second is the “agon” (meaning struggle or combat) model, in which it is God’s victory in battle over the monsters of the sea that mark his sovereignty and might.

Genesis 1 is the supreme example of the “logos” mythology; Isaiah 51:9–10 recalls an ancient Canaanite myth in which God creates the world by vanquishing the water deities: “Awake, awake! … It was you that hacked Rahab in pieces, that pierced the Dragon! It was you that dried up the Sea, the waters of the great Deep, that made the abysses of the Sea a road that the redeemed might walk…”

Monotheism

Monotheism is defined by the Encyclopædia Britannica as belief in the existence of one god or in the oneness of God. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church gives a more restricted definition: “belief in one personal and transcendent God”, as opposed to polytheism and pantheism.

A distinction may be made between exclusive monotheism, and both inclusive monotheism and pluriform monotheism which, while recognising many distinct gods, postulate some underlying unity.

Monotheism characterizes the traditions of Babism, the Bahá’í Faith, Cao Dai (Caodaiism), Cheondoism (Cheondogyo), Christianity, Deism, Eckankar, Islam, Judaism, Rastafari, Ravidassia religion, Seicho no Ie, Shaivism, Shaktism, Sikhism, Tenrikyo (Tenriism), Vaishnavism, and Zoroastrianism and elements of the belief are discernible in numerous other religions including Atenism and Ancient Chinese religion.

The word monotheism comes from the Greek monos meaning “single” and theos meaning “god”. The English term was first used by Henry More (1614–1687).

In Zoroastrianism, one of the earliest documented instances of the emergence of monism in an Indo-European religion, Ahura Mazda appears as a supreme and transcendental deity. Depending on the date of Zoroaster, who usually considered to be contemporary with the Vedas.

Monolatrism can be a stage in the development of monotheism from polytheism. Three examples of this are the Aten cult in the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten, the rise of Marduk from the tutelary of Babylon to the claim of universal supremacy, and the rise of Yahweh from among the Canaanite gods to the sole God of Judaism.

Ethical monotheism and the associated concept of absolute good and evil emerge in Zoroastrianism and Judaism, later culminating in the doctrines of Christology in early Christianity and later (by the 7th century) in the tawhid in Islam.

In the cities of the Ancient Near East, each city had a local patron deity, such as Shamash at Larsa or Sin at Ur. The first claims of global supremacy of a specific god date to the Late Bronze Age, with Akhenaten’s Great Hymn to the Aten.

However the historicity of the Exodus is disputed. Furthermore it is not clear to what extent Akhenaten’s Atenism was monotheistic rather than henotheistic with Akhenaten himself identified with the god Aten.

Currents of monism or monotheism emerge in Vedic India earlier, chiefly with worship of Lord Krishna, which is full-fledged monotheism, but also with e.g. the Nasadiya Sukta (after the incipit ná ásat “not the non-existent”), also known as the Hymn of Creation, the 129th hymn of the 10th Mandala of the Rigveda (10:129). It is concerned with cosmology and the origin of the universe.

In the Indo-Iranian tradition, the Rigveda exhibits notions of monism, in particular in the comparatively late tenth book, also dated to the early Iron Age, e.g. in the Nasadiya sukta.

According to Christian tradition, monotheism was the original religion of humanity but was generally lost after the fall of man. This theory was largely abandoned in the 19th century in favour of an evolutionary progression from animism via polytheism to monotheism, but by 1974 this theory was less widely held.

Austrian anthropologist Wilhelm Schmidt had postulated an Urmonotheismus, “original” or “primitive monotheism” in the 1910s. It was objected that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam had grown up in opposition to polytheism as had Greek philosophical monotheism. Furthermore, while belief in a “high god” is not universal, it is found in many parts of Africa and numerous other areas of the world.

Mesopotamian religion

Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Sumerian and East Semitic Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian and later migrant Arameans and Chaldeans, living in Mesopotamia (a region encompassing modern Iraq, Kuwait, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria) that dominated the region for a period of 4200 years from the fourth millennium BCE throughout Mesopotamia to approximately the 10th century CE in Assyria.

Mesopotamian polytheism was the only religion in ancient Mesopotamia for thousands of years before entering a period of gradual decline beginning between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. This decline happened in the face of the introduction of a distinctive native Eastern Christianity (Syriac Christianity such as the Assyrian Church of the East and Syriac Orthodox Church) as well as Judaism, Manichaeism and Gnosticism, and continued for approximately three to four centuries, until most of the original religious traditions of the area died out, with the final traces existing among some remote Assyrian communities until the 10th century CE.

As with most dead religions, many aspects of the common practices and intricacies of the doctrine have been lost and forgotten over time. Fortunately, much of the information and knowledge has survived, and great work has been done by historians and scientists, with the help of religious scholars and translators, to re-construct a working knowledge of the religious history, customs, and the role these beliefs played in everyday life in Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia during this time.

Mesopotamian religion is thought to have been a major influence on subsequent religions throughout the world, including Canaanite, Aramean, ancient Greek, and Phoenician religions, and also monotheistic religions such as Judaism, Christianity, Mandaeism and Islam.

It is known that the god Ashur, among others, was still worshipped in Assyria as late as the 4th century CE. Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic, worshipping over 2,100 different deities, many of which were associated with a specific city or state within Mesopotamia such as Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Assur, Nineveh, Ur, Uruk, Mari and Babylon.

Historians, such as Jean Bottéro, have made the claim that Mesopotamian religion is the world’s oldest religion, although there are several other claims to that title. However, as writing was invented in Mesopotamia it is certainly the oldest in written history.

What is known about Mesopotamian religion comes from archaeological evidence uncovered in the region, particularly literary sources, which are usually written in cuneiform on clay tablets and which describe both mythology and cultic practices. Other artifacts can also be useful when reconstructing Mesopotamian religion.

As is common with most ancient civilizations, the objects made of the most durable and precious materials, and thus more likely to survive, were associated with religious beliefs and practices. This has prompted one scholar to make the claim that the Mesopotamians’ “entire existence was infused by their religiosity, just about everything they have passed on to us can be used as a source of knowledge about their religion.”

Although, a few isolated pockets in Assyria/Upper Mesopotamia aside, it largely died out by approximately 400 CE, Mesopotamian religion has still had an influence on the modern world, predominantly because many biblical stories that are today found in Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Mandaeism were possibly originally based upon earlier Mesopotamian myths, in particular that of the creation myth, the Garden of Eden, the flood myth, the Tower of Babel and figures such as Nimrod and Lilith.

In addition, the story of Moses’ origins shares a similarity with that of Sargon of Akkad, and the Ten Commandments mirror Assyrian-Babylonian legal codes to some degree. It has also inspired various contemporary neopagan groups to begin worshipping the Mesopotamian deities once more, albeit in a way often different from that of the Mesopotamian people themselves.

Panbabylonism

In the New Testament book of Revelation, Babylonian religion is associated with religious apostacy of the highest order, the archetype of a political/religious system heavily tied to global commerce, and it is depicted as a system which, according to the author, continued to hold sway in the first century CE, eventually to be utterly annihilated.

According to some interpretations, this is believed to refer to the Roman Empire, but according to other interpretations, this system remains extant in the world until the Second Coming of Christ.

Jowever, according to a theory developed in the late Nineteenth century called Panbabylonism, many of the stories of the Tanakh, the Old Testament and the Qur’an are believed to have been based on, influenced by, or inspired by the earlier legendary mythological past of Mesopotamia, which for centuries dominated the entire region.

The Enuma Elish in particular has been compared to the later Genesis creation narrative. The story of Esther in particular is traced to Assyro-Babylonian roots. Others include The Great Flood and Noah’s Ark which may well have been influenced by the earlier Epic of Gilgamesh narratives.

The story of the biblical hunter-king Nimrod (a ruler not attested in Mesopotamian annals) is believed to have been inspired by the real Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I, or alternatively by the Assyrian war god Ninurta. Others include Lilith, who seems to have been based on the Assyrian demoness Lilitu, and the Tower of Babel inspired by the impressive Ziggurats of Assyria and Babylonia.

Jewish, Christian, and Islamic believers address the assertion that parts of the Bible may derive from pagan texts, apologists point out that the differences between the Bible and Mesopotamian texts far outweigh the similarities, and that there is, at least, nothing about the ancient texts that indicates the biblical stories were directly copied from the older Mesopotamian ones. Instead, they may both draw from even older sources.

For example, the Flood story appears in almost every culture around the world, including cultures that never had contact with Mesopotamia. Other apologists point out that the Mesopotamian texts appear highly embellished compared to the simpler Biblical texts, which bear closer resemblance to the creation account described in tablets discovered at Ebla in 1968.

However, much of the initial media excitement about supposed Eblaite connections with the Bible, based on preliminary guesses and speculations by Pettinato and others, is now widely deplored as generated by “exceptional and unsubstantiated claims” and “great amounts of disinformation that leaked to the public”. The present consensus is that Ebla’s role in biblical archaeology, strictly speaking, is minimal.

The creation

Stories describing creation are prominent in many cultures of the world. Unfortunately, very little survives of Sumerian literature from the third millennium B.C. There are no specific written records explaining Mesopotamian religious cosmology that survive to us today. Nonetheless, modern scholars have examined various accounts, and created what is believed to be an at least partially accurate depiction of Mesopotamian cosmology.

In Mesopotamia, the surviving evidence from the third millennium to the end of the first millennium B.C. indicates that although many of the gods were associated with natural forces, no single myth addressed issues of initial creation. It was simply assumed that the gods existed before the world was formed.

However, several fragmentary tablets contain references to a time before the pantheon of the gods, when only the Earth (Sumerian: ki) and Heavens (Sumerian: an) existed. All was dark, there existed neither sunlight nor moonlight; however, the earth was green and water was in the ground, although there was no vegetation.

More is known from Sumerian poems that date to the beginning centuries of the second millennium BC. A Sumerian myth, known today as Gilgamesh and the Netherworld (also known as “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld” and variants), opens with a mythological prologue.

It assumes that the gods and the universe already exist and that once a long time ago the heavens and earth were united, only later to be split apart. Later, humankind was created and the great gods divided up the job of managing and keeping control over heavens, earth, and the Netherworld.

Seven debate topics are known from the Sumerian literature, falling in the category of disputations; some examples are: The Debate between sheep and grain; The Debate between bird and fish; the Debate between Winter and Summer; and The Dispute between Silver and Copper, etc.

These topics came some centuries after writing was established in Sumerian Mesopotamia. The debates are philosophical and address humanity’s place in the world. Some of the debates may be from 2100 BC. The Song of the Hoe or the Creation of the Pickax stands alone in its own sub-category as a one-sided debate poem.

The Song of the Hoe

In the Sumerian poem The Song of the Hoe or the Creation of the Pickax, as in many other Sumerian stories, the god Enlil is described as the deity who separates heavens and earth in Duranki, the cosmic Nippur or Garden of the Gods, and creates humankind. Humanity is formed to provide for the gods, a common theme in Mesopotamian literature.

One of the tablets from the Yale Babylonian Collection was published by J.J. Van Dijk which spoke of three cosmic realms; heaven, earth and kur in a time when darkness covered an arid land, when heaven and earth were joined and the Enlil’s universal laws, the me did not function.

The myth continues with a description of Enlil creating daylight with his hoe; he goes on to praise its construction and creation. Enlil’s mighty hoe is said to be made of gold, with the blade made of lapis lazuli and fastened by cord. It is inlaid with lapis lazuli and adorned with silver and gold.

Enlil makes civilized man, from a brick mould with his hoe – and the Annanuki start to praise him. Nisaba, Ninmena, and Nunamnir start organizing things. Enki praises the hoe; they start reproducing and Enlil makes numerous shining hoes, for everyone to begin work.

Two of the major traditions of the Sumerian concept of the creation of man are discussed in the myth. The first is the creation of mankind from brick moulds or clay. This has notable similarities to the creation of man from the dust of the earth in the Book of Genesis in the Bible (Genesis 2:6-7). This activity has also been associated with creating clay figurines.

The second Sumerian tradition which compares men to plants, made to “break through the ground”, an allusion to imagery of the fertility or mother goddess and giving an image of man being “planted” in the ground.

Wayne Horowitz notes that five Sumerian myths recount a creation scene with the separation of heaven and earth. He further notes the figurative imagery relaying the relationship between the creation of agricultural implements making a function for mankind and thereby its creation from the “seed of the land”. The myth was called the “Creation of the Pickax” by Samuel Noah Kramer, a name by which it is referred in older sorurces.

In Sumerian literature, the hoe or pickaxe is used not only in creation of the Ekur but also described as the tool of its destruction in lament hymns such as the Lament for Ur, where it is torn apart with a storm and then pickaxes.

Enlil then founds the Ekur, a Sumerian term meaning “mountain house”, the assembly of the gods in the Garden of the gods, parallel in Greek mythology to Mount Olympus, with his hoe whilst a “god-man” called Lord Nudimmud builds the Abzu in Eridug.

Various gods are then described establishing construction projects in other cities, such as Ninhursag in Kesh, and Inanna and Utu in Zabalam; Nisaba and E-ana also set about building. The useful construction and agricultural uses of the hoe are summarized, along with its capabilities for use as a weapon and for burying the dead.

Allusions are made to the scenes of Enkidu’s ghost, and Urshanabi’s ferry over the Hubur, in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Ninmena is suggested to create both the priestess and king. The hymn ends with extensive praisings of the hoe, Enlil, and Nisaba.

Modern society may have trouble comprehending the virtue of extolling a tool such as the lowly hoe, for the Sumerians the implement had brought agriculture, irrigation, drainage and the ability to build roads, canals and eventually the first proto-cities.

The Debate between Grain and Sheep

In the Sumerian poem “The Debate between Grain and Sheep,” the earth first appeared barren, without grain, sheep, or goats. People went naked. They ate grass for nourishment and drank water from ditches. Later, the gods created sheep and grain and gave them to humankind as sustenance.

The story opens with a location “the hill of heaven and earth” which is discussed by Chiera as “not a poetical name for the earth, but the dwelling place of the gods, situated at the point where the heavens rest upon the earth. It is there that mankind had their first habitat, and there the Babylonian Garden of Eden is to be placed.”

Jeremy Black suggests this area was restricted for gods, noting that field plans from the Third dynasty of Ur use the term hursag (“hill”) to describe the hilly parts of fields that are hard to cultivate due to the presence of prehistoric tell mounds (ruined habitations).

Kramer discusses the story of the god An creating the cattle-goddess, Lahar, and the grain goddess, Ashnan, to feed and clothe the Annunaki, who in turn made man. Lahar and Ashnan are created in the “duku” or “pure place” and the story further describes how the Annunaki create a sheepfold with plants and herbs for Lahar and a house, plough and yoke for Ashnan, describing the introduction of animal husbandry and agriculture.

The story continues with a quarrel between the two goddesses over their gifts which eventually resolves with Enki and Enlil intervening to declare Ashnan the victor.

Samuel Noah Kramer has noted the parallels and variations between the story and the later one of Cain and Abel , according to the Book of Genesis, two sons of Adam and Eve, in the Bible Book of Genesis (Genesis 4:1-16).

Cain is described as a crop farmer and his younger brother Abel as a shepherd. Cain was the first human born and Abel was the first human to die. Cain committed the first murder by killing his brother. Interpretations of Genesis 4 by ancient and modern commentators have typically assumed that the motives were jealousy and anger. Abel, the first murder victim, is sometimes seen as the first martyr; while Cain, the first murderer, is sometimes seen as an ancestor of evil.

Cain and Abel are traditional English renderings of the Hebrew names Qayin and Hevel. The original text did not provide vowels. It has been proposed that the etymology of their names may be a direct pun on the roles they take in the Genesis narrative.

Abel is thought to derive from a reconstructed word meaning “herdsman”, with the modern Arabic cognate ibil now specifically referring only to “camels”. Cain is thought to be cognate to the mid-1st millennium BC South Arabian word qyn, meaning “metalsmith”.

This theory would make the names descriptive of their roles, where Abel works with livestock, and Cain with agriculture—and would parallel the names Adam (“man,” אדם) and Eve (“life-giver,” חוה Chavah).

Modern scholars typically view the stories of Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel to be about the development of civilization during the age of agriculture; not the beginnings of man, but when people first learned agriculture, replacing the ways of the hunter-gatherer.

Emesh and Enten, Cain and Abel

Many scholars have pointed to the similarities between the Sumerian tale of Emesh and Enten and the biblical tale of Cain and Abel. Samuel Noah Kramer called the Emesh and Enten tale “the closest extant Sumerian parallel to the Biblical Cain and Abel story”.

The Emesh and Enten tale is found on clay tablets from the 3rd millennium BCE while the oldest source of the Hebrew Bible is thought to have been written during the 6th century BCE.

In the Sumerian tale, the god Enlil has sex with the Earth, which gives birth to two boys named Emesh and Enten. Emesh is a personification of summer and Enten a personification of winter. Each brother brings an offering to Enlil, but Enten becomes angry with Emesh and the two begin an argument.

In Genesis, Adam has sex with Eve, who gives birth to two boys named Cain and Abel. Cain worked the soil and Abel kept flocks. Each brother brings an offering to Yahweh. Yahweh looks favorably on Abel’s offering but not on Cain’s, so Cain becomes angry.[Genesis 4:1-5]

At this point, however, the similarities end. In the Sumerian tale, Enlil intervenes and declares Enten the winner of the debate. Emesh accepts Enlil’s judgment and the brothers reconcile. In Genesis, Cain murders his brother Abel.[Genesis 4:8]

The Debate between Bird and Fish

The bird and fish debate is a 190-line text of cuneiform script. It begins with a discussion of the gods having given Mesopotamia and dwelling places for humans; for water for the fields, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, and the marshes, marshland, grazing lands for humans, and the birds of the marshes, and fish are all given.

According to The Debate between Bird and Fish, water for human consumption did not exist until Enki, lord of wisdom, created the Tigris and Euphrates and caused water to flow into them from the mountains.

He also created the smaller streams and watercourses, established sheepfolds, marshes, and reedbeds, and filled them with fish and birds. He founded cities and established kingship and rule over foreign countries.

The Debate between Winter and Summer

In The Debate between Winter and Summer or Myth of Emesh and Enten, an unknown Sumerian author explains that summer and winter, abundance, spring floods, and fertility are the result of Enlil’s copulation with the hills of the earth.

The story takes the form of a contest poem between two cultural entities first identified by Kramer as vegetation gods, Emesh and Enten. These were later identified with the natural phenomena of Winter and Summer. The location and occasion of the story is described in the introduction with the usual creation sequence of day and night, food and fertility, weather and seasons and sluice gates for irrigation.

Samuel Noah Kramer has noted this myth “is the closest extant Sumerian parallel to the Biblical Cain and Abel story” in the Book of Genesis (Genesis 4:1-16). This connection has been made by other scholars. The disputation form has also been suggested to have similar elements to the discussions between Job and his friends in the Book of Job.

Ekur

Ekur was the most revered and sacred building of ancient Sumer. The splendour of the designs and decorations led Age Westenholz to suggest the anaology of this spiritual sanctuary to the Sumerian empire with that of the Vatican to the Roman Catholic world. The chief administrator of the Ekur or “sanga” of Enlil was appointed by the king and held special status in Nippur and votive inscriptions of the kings indicate that it had held this position since early dynastic times.

There is a clear association of Ziggurats with mountain houses. Mountain houses play a certain role in Mesopotamian mythology and Assyro-Babylonian religion, associated with deities such as Anu, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursag. In the Hymn to Enlil, the Ekur is closely linked to Enlil whilst in Enlil and Ninlil it is the abode of the Annanuki, from where Enlil is banished.

In mythology, the Ekur was the centre of the earth and location where heaven and earth were united. It is also known as Duranki and one of its structures is known as the Kiur (“great place”). Enamtila has also been suggested by Piotr Michalowski to be a part of the Ekur.

A hymn to Nanna illustrates the close relationship between temples, houses and mountains. “In your house on high, in your beloved house, I will come to live, O Nanna, up above in your cedar perfumed mountain“. This was carried-on into later tradition in the Bible by the prophet Micah who envisions “the mountain of the temple of Yahweh”.

The Tummal Inscription records the first king to build a temple to Enlil as Enmebaragesi, the predecessor of Gilgamesh, around 2500 BC. Ekur is generally associated with the temple at Nippur restored by Naram-Sin of Akkad and Shar-Kali-Sharri during the Akkadian Empire. It is also the later name of the temple of Assur rebuilt by Shalmaneser I.

The word can also refer to the chapel of Enlil in the temple of Ninimma at Nippur. It is also mentioned in the Inscription of Gaddas as a temple of Enlil built “outside Babylon”, possibly referring to the Enamtila in western Babylon.

A hymn to Urninurta mentions the prominence of a tree in the courtyard of the Ekur, reminiscent of the tree of life in the Garden of Eden: “O, chosen cedar, adornment of the yard of Ekur, Urinurta, for thy shadow the country may feel awe!”. This is suggested by G. Windgren to reflect the concept of the tree as a mythical and ritual symbol of both king and god.

Hymn to Enlil

The Hymn to Enlil, Enlil and the Ekur (Enlil A), Hymn to the Ekur, Hymn and incantation to Enlil, Hymn to Enlil the all beneficent or Excerpt from an exorcism is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets in the late third millennium BC. Andrew R. George suggested that the hymn to Enlil “can be incorporated into longer compositions” as with the Kesh temple hymn and “the hymn to temples in Ur that introduces a Shulgi hymn.”

The hymn, noted by Kramer as one of the most important of its type, starts with praise for Enlil in his awe-inspiring dais. The hymn develops by relating Enlil founding and creating the origin of the city of Nippur and his organization of the earth.

In contrast to the myth of Enlil and Ninlil where the city exists before creation, here Enlil is shown to be responsible for its planning and construction, suggesting he surveyed and drew the plans before its creation.

The hymn moves on from the physical construction of the city and gives a description and veneration of its ethics and moral code. The last sentence has been compared by R. P. Gordon to the description of Jerusalem in the Book of Isiah (Isiah 1:21), “the city of justice, righteousness dwelled in her” and in the Book of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 31:23), “O habitation of justice, and mountain of holiness.”

A similar passage to the last lines above has been noted in the Biblical Psalms (Psalms 29:9) “The voice of the Lord makes hinds to calve and makes goats to give birth (too) quickly”. The hymn concludes with further reference to Enlil as a farmer and praise for his wife, Ninlil.

The poetic form and laudatory content of the hymn have shown similarities to the Book of Psalms in the Bible, particularly Psalm 23 (Psalms 23:1-2) “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want, he maketh me to lie down in green pastures.”

Line eighty four mentions: ”Enlil, if you look upon the shepherd favourably, if you elevate the one truly called in the Land, then the foreign countries are in his hands, the foreign countries are at his feet! Even the most distant foreign countries submit to him.”

In line ninety one, Enlil is referred to as a shepherd: “Enlil, faithful shepherd of the teeming multitudes, herdsman, leader of all living creatures.” The shepherd motif originating in this myth is also found describing Jesus in the Book of John (John 10:11-13).

The foundations of Enlil’s temple are made of lapis lazuli, which has been linked to the “soham” stone used in the Book of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 28:13) describing the materials used in the building of “Eden, the Garden of god” perched on “the mountain of the lord”, Zion, and in the Book of Job (Job 28:6-16) “The stones of it are the place of sapphires and it hath dust of gold”.

Moses also saw God’s feet standing on a “paved work of a sapphire stone” in (Exodus 24:10). Precious stones are also later repeated in a similar context describing decoration of the walls of New Jerusalem in the Apocalypse (Revelation 21:21).

Lament of Ur

The fall of Ekur is described in the Lament for Ur or Lamentation over the city of Ur, a Sumerian lament composed around the time of the fall of Ur to the Elamites and the end of the city’s third dynasty (c. 2000 BC). It contains one of five known Mesopotamian “city laments”—dirges for ruined cities in the voice of the city’s tutelary goddess. The other city laments are The Lament for Sumer and Ur, The Lament for Nippur, The Lament for Eridu, and The Lament for Uruk.

The Book of Lamentations of the Old Testament, which bewails the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon in the sixth century BC., is similar in style and theme to these earlier Mesopotamian laments. Similar laments can be found in the Book of Jeremiah, the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Psalms, Psalm 137 (Psalms 137:1-9), a song covered by Boney M in 1978 as Rivers of Babylon.

Enlil

The ancient Sumerian chief deity was Enlil, the Lord of the Wind. Enlil owed nominal loyalty to his father Anu/Heaven but outside of southern Mesopotamia he gradually became more important evolving to the status of king of the gods. In Canaan Enlil was known as El, the father of an entire pantheon of gods.

In the second verse of Genesis God, who is called Elohim (literally the plural “Gods”) in the Hebrew, is said to hover over the waters. This description of God and the use of the name Elohim further reveals this Mesopotamian god’s influence.

Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters (Genesis 1:2). This image of God moving over the waters compares directly with the mythology of Enlil who was made visible by traces of his passing such as ripples on the water.

Chaos

Tiamat is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation, depicted as a woman she represents the beauty of the feminine, depicted as the glistening one. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon. She was the “shining” personification of salt water who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Apsu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is “Ummu-Hubur who formed all things”.

Thorkild Jacobsen and Walter Burkert both argue for a connection with the Akkadian word for sea, tâmtu, following an early form, ti’amtum. Tiamat also has been claimed to be cognate with Northwest Semitic tehom (תהום) (the deeps, abyss), in the Book of Genesis 1:2.

Greek χάος (Chaos) means “emptiness, vast void, chasm, abyss”, from the verb χαίνω, “gape, be wide open, etc.”, from Proto-Indo-European *ǵhehn, cognate to Old English geanian, “to gape”, whence English yawn. It may also mean space, the expanse of air, and the nether abyss, infinite darkness. It refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, or to the initial “gap” created by the original separation of heaven and earth.

Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 6th century BC) interpretes chaos as water, like something formless which can be differentiated. Hesiod and the Pre-Socratics use the Greek term in the context of cosmogony. Hesiod’s “chaos” has been interpreted as a moving, formless mass from which the cosmos and the gods originated.

In Hesiod’s opinion the origin should be indefinite and indeterminate, and it represents disorder and darkness. Chaos has been linked with the term tohu wa-bohu of Genesis 1:2. The term may refer to a state of non-being prior to creation or to a formless state.

In the Book of Genesis, the spirit of God is moving upon the face of the waters, and the earliest state of the universe is like a “watery chaos”. The Septuagint makes no use of χάος in the context of creation, instead using the term for גיא, “chasm, cleft”, in Micha 1:6 and Zacharia 14:4.

In one interpretation, Genesis 1:1-3 can be taken as describing the state of chaos immediately before God’s act of creation: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.”

Of the certain uses of the word chaos in Theogony, in the creation the word is referring to a “gaping void” which gives birth to the sky, but later the word is referring to the gap between the earth and the sky, after their separation.

A parallel can be found in the Genesis. In the beginning God creates the earth and the sky. The earth is “formless and void” (tohu wa-bohu), and later God divides the waters under the firmament from the waters over the firmament, and calls the firmament “heaven”.

Nevertheless, the term chaos has been adopted in religious studies as referring to the primordial state before creation, strictly combining two separate notions of primordial waters or a primordial darkness from which a new order emerges and a primordial state as a merging of opposites, such as heaven and earth, which must be separated by a creator deity in an act of cosmogony. In both cases, chaos referring to a notion of a primordial state contains the cosmos in potentia but needs to be formed by a demiurge before the world can begin its existence.

This model of a primordial state of matter has been opposed by the Church Fathers from the 2nd century, who posited a creation ex nihilo by an omnipotent God.

In modern biblical studies, the term chaos is commonly used in the context of the Torah and their cognate narratives in Ancient Near Eastern mythology more generally. Parallels between the Hebrew Genesis and the Babylonian Enuma Elish were established by Hermann Gunkel in 1910. Besides Genesis, other books of the Old Testament, especially a number of Psalms, some passages in Isaiah and Jeremiah and the Book of Job are relevant.

Use of chaos in the derived sense of “complete disorder or confusion” first appears in Elizabethan Early Modern English, originally implying satirical exaggeration.

Hubur

Hubur (ḪU.BUR, Hu-bur) is a Sumerian term meaning “river”, “watercourse” or “netherworld”. It is usually the “river of the netherworld”. A connection to Tiamat has been suggested with parallels to her description as “Ummu-Hubur”. Hubur is also referred to in the Enuma Elish as “mother sea Hubur, who fashions all things”.

The river Euphrates has been identified with Hubur as the source of fertility in Sumer. The Khabur or Khaboor River is the largest perennial tributary to the Euphrates in Syrian territory. Several important wadis join the Khabur north of Al-Hasakah, together creating what is known as the Khabur Triangle, or Upper Khabur area.

This Babylonian “river of creation” has been linked to the Hebrew “river of paradise”. Gunkel and Zimmern suggested resemblance in expressions and a possible connection between the Sumerian river and that found in later literary tradition in the Book of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 47) likely influencing imagery of the “River of Water of Life” in the Apocalypse (Revelation 22).

They also noted a connection between the “Water of Life” in the legend of Adapa and a myth translated by A.H. Sayce called “An address to the river of creation”. Delitzch has suggested the similar Sumerian word Habur probably meant “mighty water source”, “source of fertility” or the like. This has suggested the meaning of Hubur to be “river of fertility in the underworld”.

Linda Foubister has suggested the river of creation was linked with the importance of rivers and rain in the Fertile Crescent and suggested it was related to the underworld as rivers resemble snakes.

Samuel Eugene Balentine suggested that the “pit” (sahar) and “river” or “channel” (salah) in the Book of Job (Job 33:18) were referencing the Hubur. The god Marduk was praised for restoration or saving individuals from death when he drew them out of the waters of the Hubur, a later reference to this theme is made in Psalm 18 (Psalms 18).

Chaoskampf

It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos, the first in which Tiamat is a creator goddess, through a “Sacred marriage” between salt and fresh water, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second “Chaoskampf” Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.

The motif of Chaoskampf (German for “struggle against chaos”) is ubiquitous in myth and legend, depicting a battle of a culture hero deity with a chaos monster, often in the shape of a serpent or dragon. The same term has also been extended to parallel concepts in the religions of the Ancient Near East, such as the abstract conflict of ideas in the Egyptian duality of Maat and Isfet.

Indo-European examples of this mythic trope include Thor vs. Jörmungandr (Norse), Tarhunt vs. Illuyanka (Hittite), Indra vs. Vritra (Vedic), Θraētaona vs. Aži Dahāka (Avestan), and Zeus vs. Typhon (Greek) among others. Examples of the storm god vs. sea serpent trope in the Ancient Near East can be seen with Baʿal vs. Yam (Canaanite), Marduk vs. Tiamat (Babylonian), Ra vs. Apep (Egyptian Mythology), and Yahweh vs. Leviathan (Jewish) among others.

The Chaoskampf would eventually be inherited by descendants of these ancient religions, perhaps most notably by Christianity. Examples include the story of Saint George and the Dragon (most probably descended from the Slavic branch of Indo-European and stories such as Dobrynya Nikitich vs. Zmey Gorynych).

Some scholars argue that this extends to Christ and/or Saint Michael vs. the Devil (as seen in the Book of Revelation among other places and probably related to the Yahweh vs. Leviathan and later Gabriel vs. Rahab stories of Jewish mythology), but this is hotly contested.

Even more controversial is the view that the narrative appears in the crucifixion story of Jesus found in the gospels, a view debated by scholars such as Walter Wink, who indicates that the gospel accounts of Christ’s death present the diametric opposite thematic viewpoint presented in the Chaoskampf myths.

Lôtān, Litan, or Litānu (Ugaritic: Ltn, lit. “Coiled”) was a sea monster in Canaanite mithology, better known as Leviathan in Hebrew mythology. Lotan seems to have been prefigured by Têmtum, the serpent killed by the benevolent storm god Hadad in Syrian seals of the 18th–16th century BC.

In the Baal Cycle discovered in the ruins of Ugarit, Lotan is a servant of the sea god Yammu and is defeated by the benevolent storm god Baʿal, possibly with the help or by the hand of his sister ʿAnat. Lotan or Litanu was his proper name.

The account has gaps, making it unclear whether some phrases describe him or other monsters at Yammu’s disposal. Most scholars agree on describing him as “the fugitive serpent” (bṯn brḥ) but he may or may not be “the wriggling serpent” (bṯn ʿqltn) or “the mighty one with seven heads” (šlyṭ d.šbʿt rašm).

The Baal Cycle’s description of Lotan is directly paralleled by a passage in the later Apocalypse of Isaiah, where scholars are likewise uncertain as to whether two leviathans and a tannin are slain or whether all three figures refer to a single Leviathan.

Leviathan, in the Bible, one of the names of the primeval dragon subdued by Yahweh at the outset of creation: “You crushed Leviathan’s heads, gave him as food to the wild animals” (Psalm 74:14; see also Isaiah 27:1; Job 3:8; Amos 9:3). Biblical writers also refer to the dragon as Rahab (Job 9:13; Psalm 89:10) or simply as the Abyss (Habakkuk 3:10).

The biblical references to the battle between Yahweh and Leviathan reflect the Syro-Palestinian version of a myth found throughout the ancient Near East. In this myth, creation is represented as the victory of the creator-god over a monster of chaos.

The closest parallel to the biblical versions of the story appears in the Canaanite texts from Ra’s Shamrah (14th century BC), in which Baal defeats a dragonlike monster: “You will crush Leviathan the fleeing serpent; you will consume the twisting serpent, the mighty one with seven heads.” (The wording of Isaiah 27:1 draws directly on this text.)

A more ancient version of the myth occurs in the Babylonian Creation Epic, in which the storm god Marduk defeats the sea monster Tiamat and creates the earth and sky by cleaving her corpse in two.

The latter motif is reflected in a few biblical passages that extol Yahweh’s military valor: “Was it not you who split Rahab in half, who pierced the dragon through?” (Isaiah 51:9; see also Job 26:12; Psalm 74:13, 89:10).

Enuma Elish

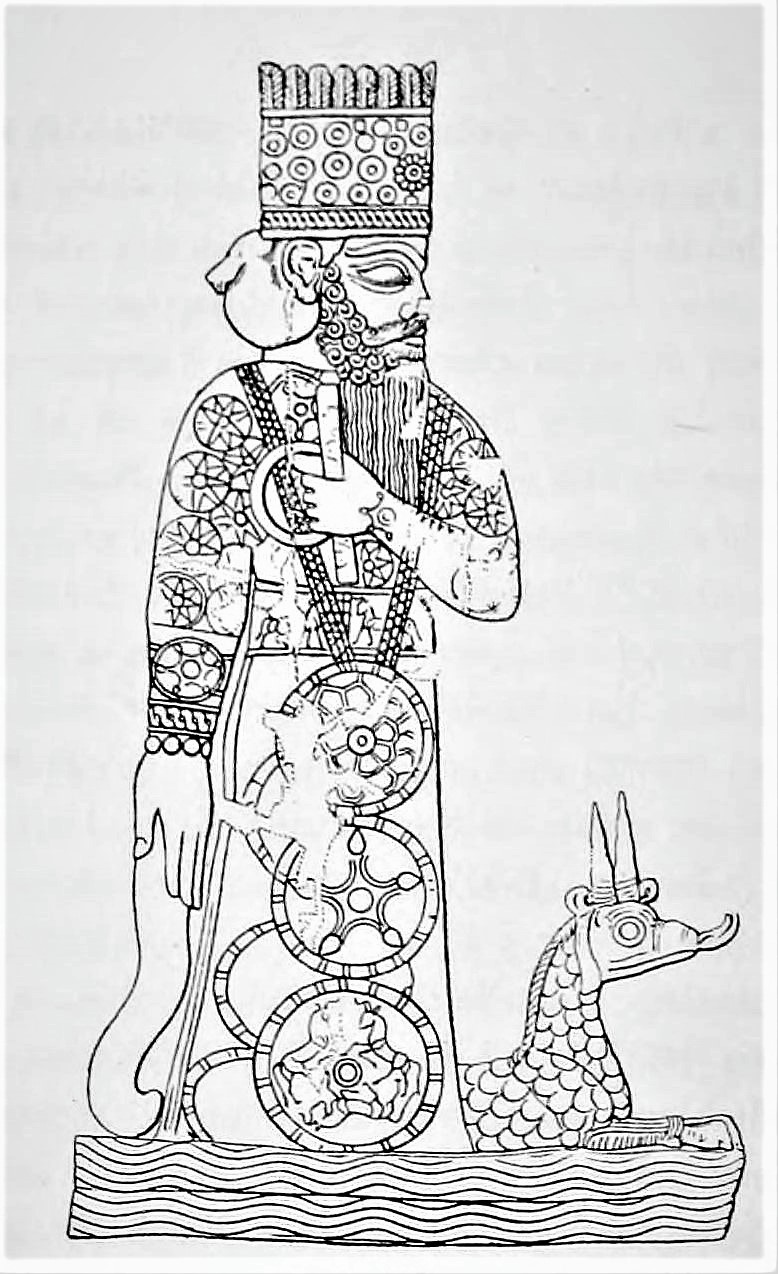

Babylonian poets, like their Sumerian counterparts, had no single explanation for creation. Diverse stories regarding creation were incorporated into other types of texts. Most prominently, the Babylonian myth “Enuma Elish”, the Babylonian creation mythos (named after its opening words) dated to 1200 BCE, is a theological legitimization of the rise of Marduk as the supreme god in Babylon, replacing Enlil, the former head of the pantheon.

One of the best-known literary texts from ancient Mesopotamia describes Marduk’s dramatic rise to power: Assyriologists refer to this composition by its ancient title Enūma eliš, Akkadian for “When on high”. It is often called “The Babylonian Epic of Creation,” which is rather a misnomer as the main focus of the story is the elevation of Marduk to the head of the pantheon, for which the creation story is only a vehicle.

The Enûma Eliš has about a thousand lines and is recorded in Old Babylonian on seven clay tablets, each holding between 115 and 170 lines of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform script. Most of Tablet V has never been recovered but, aside from this lacuna, the text is almost complete. A duplicate copy of Tablet V has been found in Sultantepe, ancient Huzirina, near the modern town of Şanlıurfa in Turkey.

The poem was most likely compiled during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in the later twelfth century B.C., or possibly a short time afterward. At this time, Babylon, after many centuries of rule by the foreign Kassite dynasty, achieved political and cultural independence. The poem celebrates the ascendancy of the city and acts as a political tractate explaining how Babylon came to succeed the older city of Nippur as the center of religious festivals.

This epic is one of the most important sources for understanding the Babylonian worldview, centered on the supremacy of Marduk and the creation of humankind for the service of the gods. Its primary original purpose, however, is not an exposition of theology or theogony but the elevation of Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, above other Mesopotamian gods.

The Enûma Eliš was recognized as being related to the Jewish Genesis creation account from its first publication (Smith 1876), and it was an important step in the recognition of the roots of the account found in the Bible and in other Ancient Near Eastern (Canaanite and Mesopotamian) myths.

Creation of man

After six generations of gods, in the Babylonian “Enuma Elish”, in the seventh generation, (Akkadian “shapattu” or sabath), the younger Igigi gods, the sons and daughters of Enlil and Ninlil, go on strike and refuse their duties of keeping the creation working.

Abzu, the god of fresh water, co-creator of the cosmos, threatens to destroy the world with his waters, and the Gods gather in terror. Enki promises to help and puts Abzu to sleep, confining him in irrigation canals and places him in the Kur, beneath his city of Eridu.

But the universe is still threatened, as Tiamat, angry at the imprisonment of Abzu and at the prompting of her son and vizier Kingu, decides to take back the creation herself. The gods gather again in terror and turn to Enki for help, but Enki who harnessed Abzu, Tiamat’s consort, for irrigation refuses to get involved.

The gods then seek help elsewhere, and the patriarchal Enlil, their father, God of Nippur, promises to solve the problem if they make him King of the Gods. In the Babylonian tale, Enlil’s role is taken by Marduk, Enki’s son, and in the Assyrian version it is Asshur.

After dispatching Tiamat with the “arrows of his winds” down her throat and constructing the heavens with the arch of her ribs, Enlil places her tail in the sky as the Milky Way, and her crying eyes become the source of the Tigris and Euphrates.

But there is still the problem of “who will keep the cosmos working”. Enki, who might have otherwise come to their aid, is lying in a deep sleep and fails to hear their cries. His mother Nammu (creatrix also of Abzu and Tiamat) “brings the tears of the gods” before Enki and says: “Oh my son, arise from thy bed, from thy (slumber), work what is wise. Fashion servants for the Gods, may they produce their bread.”

Enki then advises that they create a servant of the gods, humankind, out of clay and blood. Against Enki’s wish the Gods decide to slay Kingu, and Enki finally consents to use Kingu’s blood to make the first human, with whom Enki always later has a close relationship, the first of the seven sages, seven wise men or “Abgallu” (Ab = water, Gal = great, Lu = Man), also known as Adapa. Enki assembles a team of divinities to help him, creating a host of “good and princely fashioners”.

He tells his mother “Oh my mother, the creature whose name thou has uttered, it exists. Bind upon it the will of the Gods; Mix the heart of clay that is over the Abyss, The good and princely fashioners will thicken the clay. Thou, do thou bring the limbs into existence; Ninmah (the Earth-mother goddess (Ninhursag, his wife and consort) will work above thee. Ninti (goddess of birth) will stand by thy fashioning; Oh my mother, decree thou its (the new born’s) fate.

Adapa, the first man fashioned, later goes and acts as the advisor to the King of Eridu, when in the Sumerian Kinglist, the “Me” of “kingship descends on Eridu”. Babylonian texts talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, “the holy city, the dwelling of their [the other gods] delight”.

Samuel Noah Kramer believes that behind this myth of Enki’s confinement of Abzu lies an older one of the struggle between Enki and the Dragon Kur (the underworld).

Elevation of Marduk

In Enûma Elish, a civil war between the gods was growing to a climactic battle. The Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call and was promised the position of head god.

To prepare for battle, he makes a bow, fletches arrows, grabs a mace, throws lightning before him, fills his body with flame, makes a net to encircle Tiamat within it, gathers the four winds so that no part of her could escape, creates seven nasty new winds such as the whirlwind and tornado, and raises up his mightiest weapon, the rain-flood. Then he sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths. In his lips he holds a spell and in one hand he grasps a herb to counter poison.

First, he challenges the leader of the Anunnaki gods, the dragon of the primordial sea Tiamat, the deified ocean, often seen to represent a female principle, whereas Marduk stands for the male principle, to single combat and defeats her by trapping her with his net, blowing her up with his winds, and piercing her belly with an arrow.

Marduk is victorious, kills the mother goddess Tiamat, a primordial goddess of the ocean, mating with Abzû (the god of fresh water) to produce younger gods, and creates the world from her body.

He use half her body to create the earth, and the other half to create both the paradise of šamû and the netherworld of irṣitu. A document from a similar period stated that the universe was a spheroid, with three levels of šamû, where the gods dwelt, and where the stars existed, above the three levels of earth below it.

Then, he proceeds to defeat Kingu, who Tiamat put in charge of the army and wore the Tablets of Destiny on his breast, and “wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his” and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

In gratitude the other gods then bestow 50 names upon Marduk and select him to be their head. The number 50 is significant, because it was previously associated with the god Enlil, the former head of the pantheon, who was now replaced by Marduk.

This replacement of Enlil is already foreshadowed in the prologue to the famous Code of Hammurabi, a collection of “laws,” issued by Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE), the most famous king of the first dynasty of Babylon.

In the prologue, Hammurabi mentions that the gods Anu and Enlil determined for Marduk to receive the “Enlil-ship” (stewardship) of all the people, and with this elevated him into the highest echelons of the Mesopotamian pantheon.

It is interesting to note that Marduk had to get the consent of the assembly of gods to take on Tiamat. This is a reflection of how the people of Babylon governed themselves. The government of the gods was arranged in the same way as the government of the people. All the gods reported to Marduk just as all the nobles reported to the king. And Marduk had to listen to the assembly of gods just as the king had to listen to the assembly of people.

Though most scholarly work on the Enûma Eliš regard its primary original purpose to be the elevation of Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, above other Mesopotamian gods, researchers seeking to remove Babylonian influence onto Judaism assert counter arguments.

To address the similarities between the accounts, Christian apologist Conrad Hyers of the Princeton Theological Seminary, stated that the Genesis account polemically addressed earlier Babylonian and other pagan creation myths to “repudiate the divinization of nature and the attendant myths of divine origins, divine conflict, and divine ascent,” thus rejecting the idea that Genesis borrowed from or appropriated the form of the Enûma Eliš.

According to this theory, the Enûma Eliš was comfortable using connections between the divine and inert matter, while the aim of Genesis was supposedly to state the superiority of the Israelite god Elohim over all creation (and subsequent deities).

Biblical story of Job

Another important literary text offers a different perspective on Marduk. The composition, one of the most intricate literary texts from ancient Mesopotamia, is often classified as “wisdom literature,” and ill-defined and problematic category of Akkadian literature. Assyriologists refer to this poem as Ludlul bēl nēmeqi “Let me praise the Lord of Wisdom,” after its first line, or alternatively as “The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer”.

The literary composition, which consists of four tablets of 120 lines each, begins with a 40-line hymnic praise of Marduk, in which his dual nature is described in complex poetic wording: Marduk is powerful, both good and evil, just as he can help humanity, he can also destroy people.

The story then launches into a first-person narrative, in which the hero tells us of his continued misfortunes. It is this element that has often been compared to the Biblical story of Job.

In the end the sufferer is saved by Marduk and ends the poem by praising the god once more. In contrast to Enūma eliš the “Poem of the Righteous Sufferer” offers insights into personal relationships with Marduk. The highly complicated structure and unusual poetic language make this poem part of an elite and learned discourse.

Shabbat

Shabbat (“rest” or “cessation”) or Shabbos is Judaism’s day of rest and seventh day of the week, on which religious Jews remember the Biblical creation of the heavens and the earth in six days and the Exodus of the Hebrews, and look forward to a future Messianic Age. Shabbat observance entails refraining from work activities, often with great rigor, and engaging in restful activities to honor the day.

Judaism’s traditional position is that unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution, though some suggest other origins. Variations upon Shabbat are widespread in Judaism and, with adaptations, throughout the Abrahamic and many other religions.

Reconstruction of the broken Enûma Eliš tablet seems, however, to define the rarely attested Sapattum or Sabattum as the full moon. This word is cognate or merged with Hebrew Shabbat (cf. Genesis 2:2-3), but is monthly rather than weekly; it is regarded as a form of Sumerian sa-bat (“mid-rest”), attested in Akkadian as um nuh libbi (“day of mid-repose”). This conclusion is a contextual restoration of the damaged tablet, which is read as “[Sa]bbath shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly.”

Venus

Morning star is a name for the star Sirius, which appears in the sky just before sunrise during the Dog Days, refering to the hot, sultry days of summer, originally in areas around the Mediterranean Sea, and as the expression fit, to other areas, especially in the Northern Hemisphere.

It is also a less common name for the planet Mercury when it appears in the east before sunrise or to the planet Mercury when it appears in the west (evening sky) after sunset.

Morning star is most commonly used as a name for the planet Venus when it appears in the east before sunrise. Venus is also the Evening Star when it appears in the west (evening sky), after sunset. The ancients first thought the two were separate stars and later realized it was the same star appearing as the harbinger of the Sun in the east and marking the end of the day in the west.

The morning star is an appearance of the planet Venus, an inferior planet, meaning that its orbit lies between that of the Earth and the Sun. Depending on the orbital locations of both Venus and Earth, it can be seen in the eastern morning sky for an hour or so before the Sun rises and dims it, or in the western evening sky for an hour or so after the Sun sets, when Venus itself then sets.

It is the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and the Moon, outshining the planets Saturn and Jupiter but, while these rise high in the sky, Venus never does. This may lie behind myths about deities associated with the morning star proudly striving for the highest place among the gods and being cast down.

Inanna was associated with the planet Venus. There are hymns to Inanna as her astral manifestation. It also is believed that in many myths about Inanna, including Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld and Inanna and Shukaletuda, her movements correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.

Because of its positioning so close to Earth, Venus is not visible across the dome of the sky as most celestial bodies are; because its proximity to the sun renders it invisible during the day. Instead, Venus is visible only when it rises in the East before sunrise, or when it sets in the West after sunset.

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as single entity, but rather regarded the planet as two separate stars on each horizon as the morning and evening star. The Mesopotamians, however, most likely understood that the planet was one entity.

The discontinuous movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna’s dual nature. Inanna is related like Venus to the principle of connectedness, but this has a dual nature and could seem unpredictable. Yet as both the goddess of love and war, with both masculine and feminine qualities, Inanna is poised to respond, and occasionally to respond with outbursts of temper. Mesopotamian literature takes this one step further, explaining Inanna’s physical movements in mythology as corresponding to the astronomical movements of Venus in the sky.

Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld explains how Inanna is able to, unlike any other deity, descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East.

In Inanna and Shukaletuda, in search of her attacker, Inanna makes several movements throughout the myth that correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky. An introductory hymn explains Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be, the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West. Shukaletuda also is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly to the eastern and western horizons.

In Greek mythology, Hesperus is the Evening Star, the planet Venus in the evening. He is the son of the dawn goddess Eos (Roman Aurora) and is the half-brother of her other son, Phosphorus (also called Eosphorus; the “Morning Star”). Hesperus’ Roman equivalent is Vesper (cf. “evening”, “supper”, “evening star”, “west”). Hesperus’ father was Cephalus, a mortal, while Phosphorus’ was the star god Astraios.

Hesperus is the personification of the “evening star”, the planet Venus in the evening. His name is sometimes conflated with the names for his brother, the personification of the planet as the “morning star” Eosphorus (Greek Ἐωσφόρος, “bearer of dawn”) or Phosphorus (Ancient Greek: Φωσφόρος, “bearer of light”, often translated as “Lucifer” in Latin), since they are all personifications of the same planet Venus.

“Heosphoros” in the Greek Septuagint and “Lucifer” in Jerome’s Latin Vulgate were used to translate the Hebrew “Helel” (Venus as the brilliant, bright or shining one), “son of Shahar (god) (Dawn)” in the Hebrew version of Isaiah 14:12.

When named thus by the ancient Greeks, it was thought that Eosphorus (Venus in the morning) and Hesperos (Venus in the evening) were two different celestial objects. The Greeks later accepted the Babylonian view that the two were the same, and the Babylonian identification of the planets with the great gods, and dedicated the “wandering star” (planet) to Aphrodite (Roman Venus), as the equivalent of Ishtar.

While at an early stage the Morning Star (called Phosphorus and other names) and the Evening Star (referred to by names such as Hesperus) were thought of as two celestial objects, the Greeks accepted that the two were the same, but they seem to have continued to treat the two mythological entities as distinct.

In Greek mythology, Hesiod calls Phosphorus a son of Astraeus and Eos, but other say of Cephalus and Eos, or of Atlas. The Latin poet Ovid, speaking of Phosphorus and Hesperus (the Evening Star, the evening appearance of the planet Venus) as identical, makes him the father of Daedalion. Ovid also makes him the father of Ceyx, while the Latin grammarian Servius makes him the father of the Hesperides or of Hesperis.

Aurvandil

The names Aurvandil or Earendel are cognate Germanic personal names, continuing a Proto-Germanic reconstructed compound *auzi-wandilaz “luminous wanderer”, in origin probably the name of a star or planet, potentially the morning star (Eosphoros).

As a Germanic name, Auriwandalo is attested as a historical Lombardic prince. A Latinized version, Horvandillus, is given as the name of the father of Amleth in Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum. German Orentil (Erentil) is the hero of a medieval poem of the same name. He is son of a certain Eigel of Trier and has numerous adventures in the Holy Land.

The Old Norse variant appears in purely mythological context, linking the name to a star. The only known attestation of the Old English Earendel refers to a star exclusively.

The name is a compound whose first part goes back to *auzi- ‘dawn’, a combining form related to *austaz ‘east’, cognate with Ancient Greek ēṓs ‘dawn’, Sanskrit uṣā́s, Latin aurōra, ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *h₂éuso-s ‘dawn’.

The second part comes from *wanđilaz, a derivative of *wanđaz (cf. Old Norse vandr ‘difficult’, Old Saxon wand ‘fluctuating, variable’, English wander), from *wenđanan which gave in English wend.

Jacob Grimm (1835) emphasizes the great age of the tradition reflected in the mythological material surrounding this name, without being able to reconstruct the characteristics of the Common Germanic myth. Viktor Rydberg in his Teutonic Mythology also assumes Common Germanic age for the figure.

In the Old English poem Crist I name is taken to refer to John the Baptist, addressed as the morning star heralding the coming of Christ, the “sun of righteousness”.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (Greek Φωσφόρος Phōsphoros), a name meaning “Light-Bringer”, is the Morning Star, the planet Venus in its morning appearance. Φαοσφόρος (Phaosphoros) and Φαεσφόρος (Phaesphoros) are forms of the same name in some Greek dialects.

The Latin word corresponding to Greek “Phosphorus” is “Lucifer”. It is used in its astronomical sense both in prose and poetry. Poets sometimes personify the star, placing it in a mythological context.

Another Greek name for the Morning Star is Heosphoros (Greek Ἑωσφόρος Heōsphoros), which means “Dawn-Bringer”. The form Eosphorus is sometimes met in English, as if from Ἠωσφόρος (Ēōsphoros), which is not actually found in Greek literature, but would be the form that Ἑωσφόρος would have in some dialects.

As an adjective, the Greek word φωσφόρος is applied in the sense of “light-bringing” to, for instance, the dawn, the god Dionysos, pine torches, the day; and in the sense of “torch-bearing” as an epithet of several god and goddesses, especially Hecate but also of Artemis/Diana and Hephaestus.

The Latin word lucifer, corresponding to Greek φωσφόρος, was used as a name for the morning star and thus appeared in the Vulgate translation of the Hebrew word הֵילֵל (helel) — meaning Venus as the brilliant, bright or shining one — in Isaiah 14:12, where the Septuagint Greek version uses, not φωσφόρος, but ἑωσφόρος. As a translation of the same Hebrew word the King James Version gave “Lucifer”, a name often understood as a reference to Satan.

Modern translations of the same passage render the Hebrew word instead as “morning star”, “daystar”, “shining one” or “shining star”. In Revelation 22:16, Jesus is referred to as the morning star, but not as lucifer in Latin, nor as φωσφόρος in the original Greek text, which instead has ὁ ἀστὴρ ὁ λαμπρὸς ὁ πρωϊνός (ho astēr ho lampros ho prōinos), literally: the star the bright of the morning.

In the Vulgate Latin text of 2 Peter 1:19 the word lucifer is used of the morning star in the phrase “until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts”, the corresponding Greek word being φωσφόρος.

Lucifer

Lucifer is the King James Version rendering of the Hebrew word הֵילֵל in Isaiah 14:12. This word, transliterated hêlêl or heylel, occurs only once in the Hebrew Bible and according to the KJV based Strong’s Concordance means “shining one, morning star”.

The word Lucifer is taken from the Latin Vulgate, which translates הֵילֵל as lucifer,[Isa 14:12] meaning “the morning star, the planet Venus”, or, as an adjective, “light-bringing”. The Septuagint renders הֵילֵל in Greek as ἑωσφόρος (heōsphoros), a name, literally “bringer of dawn”, for the morning star.

Later Christian tradition came to use the Latin word for morning star, lucifer, as a proper name (“Lucifer”) for the devil; as he was before his fall. As a result Lucifer has become a by-word for Satan/the Devil in the church and in popular literature, as in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno and John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

However, the Latin word never came to be used almost exclusively, as in English, in this way, and was applied to others also, including Jesus. The image of a morning star fallen from the sky is generally believed among scholars to have a parallel in Canaanite mythology.

In Latin, the word is applied to John the Baptist and is used as a title of Jesus himself in several early Christian hymns. The morning hymn Lucis largitor splendide of Hilary contains the line: “Tu verus mundi lucifer” (you are the true light bringer of the world).

The Latin word lucifer is also used of Jesus in the Easter Proclamation prayer to God regarding the paschal candle: “May this flame be found still burning by the Morning Star: the one Morning Star who never sets, Christ your Son, who, coming back from death’s domain, has shed his peaceful light on humanity, and lives and reigns for ever and ever”.

The Latin word lucifer, corresponding to Greek φωσφόρος, was used as a name for the morning star and thus appeared in the Vulgate translation of the Hebrew word הֵילֵל (helel) — meaning Venus as the brilliant, bright or shining one — in Isaiah 14:12, where the Septuagint Greek version uses, not φωσφόρος, but ἑωσφόρος.

As a translation of the same Hebrew word the King James Version gave “Lucifer”, a name often understood as a reference to Satan. Modern translations of the same passage render the Hebrew word instead as “morning star”, “daystar”, “shining one” or “shining star”.

In Revelation 22:16 Jesus is refered to as the morning star, but not as lucifer in Latin, nor as φωσφόρος in the original Greek text, which instead has ὁ ἀστὴρ ὁ λαμπρὸς ὁ πρωϊνός (ho astēr ho lampros ho prōinos), literally: the star the bright of the morning. In the Vulgate Latin text of 2 Peter 1:19 the word lucifer is used of the morning star in the phrase “until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts”, the corresponding Greek word being φωσφόρος.

Creation of man

“The Creation of Humankind” is a bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian story also referred to in scholarly literature as KAR4. This account begins after heaven was separated from earth, and features of the earth such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and canals established.

At that time, the god Enlil addressed the gods asking what should next be accomplished. The answer was to create humans by killing Alla-gods and creating humans from their blood. Their purpose will be to labor for the gods, maintaining the fields and irrigation works in order to create bountiful harvests, celebrate the gods’ rites, and attain wisdom through study.

Another early second-millennium Sumerian myth, “Enki and the World Order,” provides an explanation as to why the world appears organized. Enki decided that the world had to be well managed to avoid chaos.

Various gods were thus assigned management responsibilities that included overseeing the waters, crops, building activities, control of wildlife, and herding of domestic animals, as well as oversight of the heavens and earth and the activities of women.

According to the Sumerian story “Enki and Ninmah,” the lesser gods, burdened with the toil of creating the earth, complained to Namma, the primeval mother, about their hard work. She in turn roused her son Enki, the god of wisdom, and urged him to create a substitute to free the gods from their toil. Namma then kneaded some clay, placed it in her womb, and gave birth to the first humans.

According to the Neo-Sumerian mythological text Enki and Ninmah, Enki is the son of An and Nammu (also Namma, spelled ideographically NAMMA = ENGUR), a primeval goddess, corresponding to Tiamat in Babylonian mythology.

Nammu was the Goddess Sea (Engur) that gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first gods, representing the Apsu, the fresh water ocean that the Sumerians believed lay beneath the earth, the source of life-giving water and fertility in a country with almost no rainfall.

Nammu is not well attested in Sumerian mythology. She may have been of greater importance prehistorically, before Enki took over most of her functions. Reay Tannahill in Sex in History (1980) singled out Nammu as the “only female prime mover” in the cosmogonic myths of antiquity.

Nammu is the goddess who “has given birth to the great gods”. It is she who has the idea of creating mankind, and she goes to wake up Enki, who is asleep in the Apsu, so that he may set the process going.

The Atrahasis-Epos has it that Enlil requested from Nammu the creation of humans. And Nammu told him that with the help of Enki (her son) she can create humans in the image of gods.

Adam and Eva

Ninti is the Sumerian goddess of life. She is also one of the eight goddesses of healing who was created by Ninhursag to heal Enki’s body. Her specific healing area was the rib. Enki had eaten forbidden flowers and was then cursed by Ninhursag, who was later persuaded by the other gods to heal him. Some scholars suggest that this served as the basis for the story of Eve created from Adam’s rib in the Book of Genesis.

Ninti, the title of Ninhursag, also means “the mother of all living”, and was a title given to the later Hurrian goddess Kheba. This is also the title given in the Bible to Eve, the Hebrew and Aramaic Ḥawwah (חוה), who was made from the rib of Adam, in a strange reflection of the Sumerian myth, in which Adam — not Enki — walks in the Garden of Paradise.

Hebat, also transcribed, Kheba or Khepat, was the mother goddess of the Hurrians, known as “the mother of all living”. She is also a Queen of the deities. During Aramaean times Hebat also appears to have become identified with the goddess Hawwah, or Eve.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a long Akkadian poem on the theme of human beings’ futile quest for immortality. A number of earlier Sumerian stories about Gilgamesh, the quasi-historical hero of the epic, seem to have been used as sources, but the Akkadian work was composed about 2000 BC. It exists in several different rescissions, none of them complete.

The goddess Aruru, the goddess of creation, makes Enkidu of clay from the river. God made Adam from clay from the soil. Both were made to do the will of the god(s), nothing more. They were both made from the same material, in the same way, for the same basic purpose.

However, there’s one huge difference. Adam was made by a god, while Enkidu was made by a goddess. So, in the 1500 years separating these two books, women went from being respected while working as prostitutes in the temple to being the first sinners ever.

Lilith

Lilith is a Hebrew name for a figure in Jewish mythology, developed earliest in the Babylonian Talmud, who is generally thought to be in part derived from a historically far earlier class of female demons (līlīṯu) in Mesopotamian religion, found in cuneiform texts of Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia.