Khaldi – Haik

Khaldi – Haik

tu = men

Urartu = Urmen = Armen

One of the great chapters in the history of Armenia is or should be the epic of the monarchy which the Assyrians called Urartu, but which was known to the Hebrews as Ararat. Herodotus called its people Alarodians. Urartu is regarded by history today as one of the earlier incarnations of Armenia.

In Urartu was manifest not only the indomitable fighting spirit of the later Armenians, but also the same tendency towards development of a higher culture. As a noted authority, H. A. B. Lynch, remarks, Urartu was “no obscure dynasty which slept secure behind the mountains, but a splendid monarchy which for more than two centuries rivalled the claims of Assyria to the dominion of the ancient world.”

Urartian, Vannic, and (in older literature) Chaldean (Khaldian, or Haldian) are conventional names for the language spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu that was located in the region of Lake Van, with its capital near the site of the modern town of Van, in the Armenian Highland, modern-day Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey.

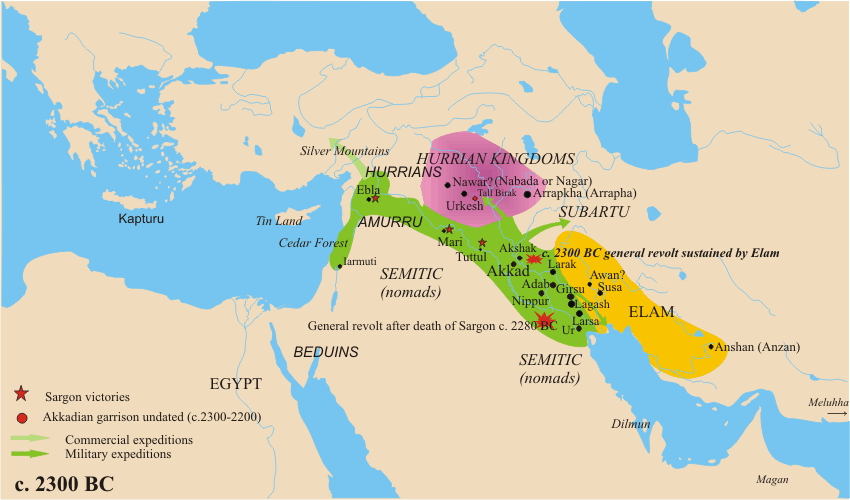

Urartian was an ergative, agglutinative language, which belongs to neither the Semitic nor the Indo-European families but to the Hurro-Urartian family (whose only other known member is Hurrian). It was probably spoken by the majority of the population around Lake Van and in the areas along the upper Zab valley.

Urartian is closely related to Hurrian, a somewhat better documented language attested for an earlier, non-overlapping period, approximately from 2000 BCE to 1200 BCE (written by native speakers until about 1350 BCE). The two languages must have developed quite independently from approximately 2000 BCE onwards.

Although Urartian is not a direct continuation of any of the attested dialects of Hurrian, many of its features are best explained as innovative developments with respect to Hurrian as we know it from the preceding millennium.

The closeness holds especially true of the so-called Old Hurrian dialect, known above all from Hurro-Hittite bilingual texts. Igor Diakonoff and others have suggested ties between the Hurro-Urartian languages and the Northeastern Caucasian languages.

Urartian survives in many inscriptions found in the area of the Urartu kingdom, written in the Assyrian cuneiform script. There have been claims of a separate autochthonous script of “Urartian hieroglyphs” but these remain unsubstantiated.

While the Armenians were known to history much earlier (for example, they were mentioned in the 6th century BC Behistun Inscription and Xenophon’s 4th century BC history, The Anabasis), the oldest surviving Armenian language text is the 5th century AD Bible translation of Mesrob Mashtots. Mesrob Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet in 405 AD, at which time it had 36 letters. He is also credited by some with the creation of the Georgian alphabet.

The large percentage of loans from Iranian languages initially led linguists to erroneously classify Armenian as an Iranian language. The distinctness of Armenian was only recognized when Hübschmann (1875) used the comparative method to distinguish two layers of Iranian loans from the older Armenian vocabulary.

W. M. Austin (1942) concluded that there was an early contact between Armenian and Anatolian languages, based on what he considered common archaisms, such as the lack of a feminine and the absence of inherited long vowels. However, unlike shared innovations (or synapomorphies), the common retention of archaisms (or symplesiomorphy) is not necessarily considered evidence of a period of common isolated development.

Soviet linguist Igor Diakonov (1985) noted the presence in Old Armenian of what he calls a Caucasian substratum, identified by earlier scholars, consisting of loans from the Kartvelian and Northeast Caucasian languages such as Udi.

Noting that the Hurro-Urartian peoples inhabited the Armenian homeland in the second millennium b.c., Diakonov identifies in Armenian a Hurro-Urartian substratum of social, cultural, and animal and plant terms such as ałaxin “slave girl” ( ← Hurr. al(l)a(e)ḫḫenne), cov “sea” ( ← Urart. ṣûǝ “(inland) sea”), ułt “camel” ( ← Hurr. uḷtu), and xnjor “apple(tree)” ( ← Hurr. ḫinzuri). Some of the terms he gives admittedly have an Akkadian or Sumerian provenance, but he suggests they were borrowed through Hurrian or Urartian.

Given that these borrowings do not undergo sound changes characteristic of the development of Armenian from Proto-Indo-European, he dates their borrowing to a time before the written record but after the Proto-Armenian language stage.

In the early 6th century BC, the Urartian Kingdom was replaced by the Armenian Orontid dynasty. In the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 521 or 520 BC by the order of Darius the Great of Persia, the country referred to as Urartu in Assyrian is called Arminiya in Old Persian and Harminuia in Elamite.

Shupria (Shubria) or Arme-Shupria (Akkadian: Armani-Subartu from the 3rd millennium BC) was a Hurrian-speaking kingdom, known from Assyrian sources beginning in the 13th century BC, located in the Armenian Highland, to the southwest of Lake Van, bordering on Ararat proper. Later, there is reference to a district in the area called Arme or Urme, which some scholars have linked to the name Armenia.

Together with Armani-Subartu (Hurri-Mitanni), Hayasa-Azzi and other populations of the region such as the Nairi fell under Urartian (Kingdom of Ararat) rule in the 9th century BC, and their descendants, according to most scholars, later contributed to the ethnogenesis of the early Armenians.

The Èr people, also known as Èrsh or (in Georgian works) the Hers, are a little-known ancient people inhabiting Northern modern Armenia, and to an extent, small areas of Northeast Turkey, Southern Georgia, and Northwest Azerbaijan.

Most of their history is constructed based on archaeological and linguistic (primarily based on placenames, with some elements) data, compared to historical trends in the region and historical writings, such as the Georgian Chronicles or the Armenian Chronicles, as well as a couple notes made by Strabo.

They were a constituent of the state of Urartu, which either incorporated or conquered them during the 8th century BCE. Their relation to the main Urartians (who were probably ethnically separate from them, judging from place names) is unknown. Linguistically, based on placenames, they are thought to have been a Nakh people.

Their language was a Nakh language. Nakh peoples are a group of historical and modern ethnic groups speaking (or historically speaking) Nakh languages and sharing certain cultural traits. In modern days, they reside almost completely in the North Caucasus, but historically certain areas of the South Caucasus may have also been Nakh.

The only healthy, living branch of the Nakh languages are now the Vainakh languages (spoken by the Vainakh peoples, namely Chechens, Ingush and Georgian Kist), due to the extinction of other peoples. The only non-Vainakh modern Nakh people are the Bats people in Northeast Georgia, but they are largely assimilated and their language is highly endangered.

Although the Vainakh are only a branch of Nakh peoples, due to the present day situation where the only well-known Nakh are Vainakh, the words Vainakh and Nakh are frequently confused. Hence the word Vainakh is frequently, but mistakenly applied to historical non-Vainakh peoples.

Nothing is really known about the people of Eriaki prior to their conquest or interpretation by Urartu, but the probably had lived separately before that. Urartu was originally situated around the Lake Van, but expanded in all directions, including North, probably eventually incorporating or conquering the Èrs.

The Urartians themselves were probably distantly related to the Èrs, in the very least by language, and probably more than just that. They were part of the same language family, the Northeast Caucasian family, and although they were of different branches, the Nakh branch is thought to be the closest to the Hurro-Urartian branch to which Urartian belongs.

The Urartian fortress Erebuni was named after them. Buni is a Nakh root, meaning shelter or home, the same root which gave rise to the modern Chechen word bun (pronounced /bʊn/), meaning a cabin, or small house. Hence, Erebuni meant “the home of the Èrs”. It corresponds to modern Yerevan (van is a common Armenian rendering for the root /bun/).

In the Georgian Chronicles, Leonti Mroveli refers to Lake Sevan as “Lake Ereta”. The name of the Arax River is also attributed to the Èrs. It is also called the Yeraskhi. The Armenian name is “Yeraskhadzor” (which Jaimoukha identifies as Èr + khi a Nakh water body suffix + Armenian dzor gorge).

The Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (Azerbaijani: Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası) is a landlocked exclave of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Armenian tradition says that Nakhchivan was founded by Noah. The oldest material culture artifacts found in the region date back to the Neolithic Age. The region was part of the states of Mannae, Urartu and Media. It became part of the Satrapy of Armenia under Achaemenid Persia 521 BC.

According to the 19th-century language scholar, Johann Heinrich Hübschmann, the name “Nakhichavan” in Armenian literally means “the place of descent”, a Biblical reference to the descent of Noah’s Ark on the adjacent Mount Ararat.

First century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus also writes about Nakhichevan, saying that its original name “Αποβατηριον, or Place of Descent, is the proper rendering of the Armenian name of this very city”.

Hübschmann notes, however, that it was not known by that name in antiquity. Instead, he states the present-day name evolved to “Nakhchivan” from “Naxčavan”. The prefix “Naxč” was a name and “avan” is Armenian for “town”. Nakhchivan was also mentioned in Ptolemy’s Geography and by other classical writers as Naxuana.

Modern historian Suren Yeremyan disputes this assertion, arguing that ancient Armenian tradition placed Nakhichevan’s founding to the year 3669 BC and, in ascribing its establishment to Noah, that it took its present name after the Armenian phrase “Nakhnakan Ichevan” (Նախնական Իջևան), or “first landing.”

Interestingly, in close proximity to the South is the “Nakhchradzor” gorge, perhaps an old home of the Dzurdzuks. During the time of the kingdom of Urartu, there was a northern region near the Yerashkhadzor gorge and a little northwest of Erebuni called “Eriaki”.

Filed under: Uncategorized