In search of the descendants of the sun

Megaliths of Shoria: The Russia Stonehenge?

Mountain Shoria, Mountainous Shoria, or Gornaya Shoria is a mountain-taiga region lying on the south of Southern Western Siberia, Russia, east of the Altay Mountains between the mountain systems of Altai and Sayan. It is the southern part of Kemerovo Oblast.

It is called after the Shors, the ingenious ancient people, very original but small one, still living there. The Shors as a people formed as a result of a long process of interbreeding between the Turkic, Ugric, Samoyedic and Ket-speaking tribes. Their culture and origins are similar to those of the northern Altay people and some of the ethnic groups of the Khakas.

The Shors were mainly engaged in hunting, fishing, some primitive farming, and pine nut picking. Blacksmithing and iron ore mining and melting were also important (hence, the name “Blacksmithing Tatars”).

Mysterious stones on Mountain Shoriya (Kemerov region, Russia) have puzzled both scientists and ordinary men. The wall of rectangular stones piled up on top of each other is already being called the “Russian Stonehenge”. According to one of the stories, they were found back in ancient times.

Though it aroused the interest of researchers in 1991, it was not explored then due to lack of financing. The research was just resumed in autumn 2013.

The Shoria site, however, isn’t in an area that’s prone to frequent earthquakes, and the stone involved is much harder than the sandstone of Yonaguni, but our weird world is known to have created some startling rock formations that defy explanation.

The Giants Causeway of Northern Ireland and The Waffle Rock of West Virginia come to mind. Both of those sites are now known to have been completely natural, but when viewed from the perspective of the layman, it seems incredible to think that they aren’t artificial constructions.

In any event, the site at Shoria has yet to be studied by experts in the field, all we have at the moment are the pictures, which in-an-of-themselves are quite impressive, but hardly conclusive. Future investigation should prove interesting.

Megaliths of Shoria: The Russia Stonehenge

Super-megalithic Site Found in Russia: Natural or Man-made?

Filed under: Uncategorized

No Gods, No Masters!

Mye tyder på at vi lever i både en spirituel verden, som ikke er åpen for vanlig dødelige, og en fysisk virkelighet som vi lever i. Mye tyder på at våre følelser og tanker, det som skjer med oss her i livet og impulser ikke kun er et spørsmål om arv og miljø, men samtidig reflekterer den spirituelle verden.

Gudene skapte menneskene erklærte sumererne, som også påsto at menneskene hadde fri vilje. I Bibelen, som for en høy grad er basert på eldre skrifter, pågår en kamp mot gudene, som blant annet inkluderer Babels tårn og språkenes forvirring, samt historien om gudenes (Enlils) forsøk på å utrydde mennesket fordi det brøt med gudens formaninger, men også gudenes (Enkis, sivilisasjonens skaper) forsøk på å redde det gode i menneskeheten via ham vi kjenner som Noah.

Spørsmålet er om disse gudene, annunakier som de ble kalt, og som betyr de med kolig blod eller pronser, representerer krefter i naturen eller om de er virkelige. De er khthoniske, et av flere ord for «jord» og det som anses som jordens indre framfor det livet som foregår på jordens ytre (et område som tilhører gaia eller ge) eller «land» (som hører til khora), fruktbarhetsguddommer forbundet med underverdenen hvor de har blitt herrer.

Annunakienes forhold til en gruppe guddommer kjent som Igigi er uklar. Noen ganger er de synonyme, men i Atra-Hasis (Noah) flodmyten er det den sjette generasjoner guder som må jobbe for anunnakiene, men gjør opprør etter 40 dager for så å bli skiftet ut av menneskene.

Vaspurakan, som betyr prinsenes land, var var den første og muligvis største provinsen i Armenia. Senere kom Vest Armenia, som i dag er en del av Tyrkia, til å bli referert til som Vaspurakan.

Uansett – “Ingen guder, ingen mestre” er en anarkistisk, feministisk og arbeiderbevegelseslagord. Dets engelske opprinnelse kommer fra en pamflett gitt ut av Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) under Lawrence tekstilstreiken i 1912. Frasen stammer fra det franske slagordet “Ni dieu ni maître!”, som litterært betyr “Hverken gud eller mestre”‘ som ble skapt av sosialisten Auguste Blanqui i 1880, da han publiserte en avis med samme navn.

Anarkisme (fra gresk ἀν (an), «uten» og ἄρχειν (arkhin), «å herske» og ισμός (ismos) (fra stammen -ιζειν), «uten herskere») er en politisk filosofi som mener staten er uønsket, unødvendig eller skadelig, og som går inn for å fjerne, eller i stor grad minske, alle former for maktstrukturer. Det er en konsekvent antiautoritær filosofi som har hatt sine røtter i alle kulturer siden urtiden.

Begrepet anarki har flere betydninger. For anarkister beskriver det en tilstand hvor folk lever i samfunn og styrer seg selv, i mest mulig grad uten hierarkisk organisasjon. Med andre ord er anarkistiske styringsformer basert på horisontal (eller flat) organisering.

Et godt eksempel på dette er samvirkebevegelsen. I motsetning til den sentralistiske staten, som styrer ovenfra (hierarkisk), er det anarkistiske alternativet et samfunn basert på desentralisering og en flat organisasjonsform der samfunnet for eksempel er organisert i mindre enheter der «hver mann er sin herre» i et kooperativt samarbeid.

Jesus var en frelser og kristendommen en frelsesreligion – det handler om å ta opp korset og vandre sammen med ham i hans kamp mot urett og svik mot mennesker og livet her på jorden! En kamp mot kapitalisme og grådighet!

Mange kristne anarkister har funnet sine utgangspunkter i håndplukkede sitater fra autoritære kirkefedre. Erklæringen fra Paulus: “Der er finnes ingen autoritet unntatt Gud,” er temmelig slitt.

Et annet velbrukt sitat er hentet fra Augustin: “Elsk, og gjør hva du vil.” Som evangelisten Johannes før ham, er Augustin inne på idéen om total frihet gjennom uselvisk nestekjærlighet, men han er allikevel en betenkelig kilde til anarkistisk filosofi. Som svar på hvorfor han trodde på evangeliet, kom han med følgende respons: “Fordi Kirken formaner meg til å tro!”

”Ned med ejendomsretten! væk med pengene! Hug dem over, de djævelske lænker der binder menneskehedens fødder til de forbandede blylodder, saa den fri og stolt kan svæve ud i rummet og jublende forfølge sin store bestemmelses maal: At erobre universet, og indrette sig i det som en herre i sit eget hus. Hvad satan nøler I efter? Hug dog lænkerne over og slip menneskeheden løs. Lad dette mangetusen-aarige vanvid endelig engang ha en ende!”, skrev Hans Jæger i Anarkiets Bibel som utkom på Gyldendal forlag i København i 1906.

Kristen-anarkisme vokser for tiden i Sør-Amerika. Kristne anarkister, som er pasifister og mot enhver bruk av vold i krig, mener at hverken regjeringen eller noen av de etablerte kirkene skal ha makt over befolkningen. Bergprekenen og Leo Tolstojs «The Kingdom of God Is Within You» er sentrale i kristne anarkistenes lære. Det er troen på at Gud er den eneste autoritet som kristne står til ansvar overfor.

Ifølge anarkistisk bibelanskuelse er det en klar overensstemmelse mellem anarkisme og Jesu lære, som flere steder er kritisk overfor kirken og status quo. Hverken regjeringen eller den etablerte kirken skal ha makt over befolkningen.»No gods, no masters» – En advarsel mot å opphøye regjering, staten, etablerte kriker og livssynssamfunn, EU og FN til guder som bare blindt følges.

Noen av de første som kalte seg anarkister i Norge, var Arne Garborg og Ivar Mortensson-Egnund. De drev det radikale målbladet Fedraheimen som kom ut 1877-91. Etter hvert ble bladet mer og mer anarkistisk orientert, og helt mot slutten av dets levetid hadde det undertittelen Anarkistisk-Kommunistisk Organ. Den anarkistiske forfatteren Hans Jæger gav i 1906 ut bokverket «Anarkiets bibel», og i nyere tid har Jens Bjørneboe vært en talsmann for anarkismen – blant annet i boken «Politi og anarki».

Margaret Sanger lanserte i 1914 Den kvinnelige opprører, en 8 siders avis som fremmet prevensjon med bruk av slagordet “No Gods, No Masters”. Hun insisterte på at hver kvinne var frue over sin egen kropp.

Lærdommen er at uansett at vi må være herrer over våre egne liv, både her i den fysiske virkeligheten og i den spirituelle verden. Vi må være herrer over både våre tanker og følelser. Vi trenger hverken guder eller andre herrer, hverken jordiske herrer som krever at vi gjør noe mer enn det kardemomme loven tilsier og ingen som legger ord i vår munn.

Å ha et trygt sted å bo, mat, klær, helseomsorg, en arbeidsplass å gå til og frihet til å leve i samsvar med sin tro – har med menneskerettigheter å gjøre. Borgerlønn, som er en universell og betingelsesløs grunninntekt, er innfrielse av menneskerettighetene i praksis. Borgerlønn kan med andre ord være med til å frigjøre oss, og våre potensialer, i en fri og horisontal verden hvor vi er herrer over oss selv.

Ny forskning på mus med lav status

Filed under: Uncategorized

I DECLARE: WE ARE ALL ONE

I DECLARE…

“That the message We Are All One, inter-related, inter-connected and inter-dependent, with God/Life/One-another, is the one spiritual message that the world has been waiting for to bring about loving and sustainable answers to humanity’s challenges.”

Have you read and signed the GLOBAL ONENESS DECLARATION? Almost 90 000 people from all over the world have. Have you shared it with your family and friends?

Oneness is the Core Reality of our existence… Let’s spread the news!

Oneness Declaration – The Text

We Only Have One Race ~ The Human Race

Filed under: Uncategorized

Mesopotamian Tree of Life

Mesopotamian Tree of Life:

This image represents the early Mesopotamian Tree of Life. In Babylonian mythology, the Tree of Life was a magical tree that grew in the center of paradise. The Apsu, or primordial waters, flowed from its roots. It is the prototype of the tree described in Genesis: the biblical Tree of Paradise evolved directly from this ancient symbol; it is the symbol from which the Egyptian, Islamic, and Kabbalistic Tree of Life concepts originated.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Magic and magicians

Pentagram

Perhaps the most well-known occult symbol of all times, the pentagram, also dates back to ancient Sumeria. In Sumerian pictographic writing, it was an ideogram used to describe Merovingian Kings as “lofty ones” or “shining ones”, and was presented in its inverted form.

The pentagram’s association with black magic probably derives from the fact that these kings were thought to possess magical powers; so it is both a symbol of their dynasty and their doctrine.

In early (Ur I) monumental Sumerian script, a pentagram glyph served as a logogram for the word ub, meaning “corner, angle, nook; a small room, cavity, hole; pitfall” (this later gave rise to the cuneiform sign UB, composed of five wedges, further reduced to four in Assyrian cuneiform).

In medieval Christian tradition, the pentagram could represent the five wounds of Jesus. In the Renaissance it came to be associated with magic and occultism, and is also found as a magic symbol in the folklore of early modern Germany (Drudenfuss).

In modern use, it is sometimes used as representing the Seal of Solomon, and it has religious significance in various new religious movements (including certain forms of Neopaganism) as well as in occultism.

-

In parts of Mesopotamian religion, magic was believed in and actively practiced. At the city of Uruk, archaeologists have excavated houses dating from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE in which cuneiform clay tablets have been unearthed containing magical incantations.

In ancient Egypt, magic consisted of four components; the primeval potency that empowered the creator-god was identified with Heka, who was accompanied by magical rituals known as Seshaw held within sacred texts called Rw. In addition Pekhret, medicinal prescriptions, were given to patients to bring relief.

This magic was used in temple rituals as well as informal situations by priests. These rituals, along with medical practices, formed an integrated therapy for both physical and spiritual health.

Magic was also used for protection against the angry deities, jealous ghosts, foreign demons and sorcerers who were thought to cause illness, accidents, poverty and infertility. Temple priests used wands during magical rituals.

Egyptians believed that with Heka, the activation of the Ka, an aspect of the soul of both gods and humans, (and divine personification of magic), they could influence the gods and gain protection, healing and transformation. Health and wholeness of being were sacred to Heka.

There is no word for religion in the ancient Egyptian language as mundane and religious world views were not distinct; thus, Heka was not a secular practice but rather a religious observance. Every aspect of life, every word, plant, animal and ritual was connected to the power and authority of the gods.

Magi (Latin plural of magus; Ancient Greek: magos; Old Persian: maguš, Persian: mogh; English singular magian, mage, magus, magusian, magusaean; Kurdish: manji) is a term, used since at least the 6th century BC, to denote followers of Zoroastrianism or Zoroaster.

The earliest known usage of the word Magi is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription.

Starting later, presumably during the Hellenistic period, the word Magi also denotes followers of what the Hellenistic chroniclers incorrectly associated Zoroaster with, which was – in the main – the ability to read the stars, and manipulate the fate that the stars foretold.

However, Old Persian texts, pre-dating the Hellenistic period, refer to a Magus as a Zurvanic, and presumably Zoroastrian, priest.

Pervasive throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia until late antiquity and beyond, mágos, “Magian” or “magician,” was influenced by (and eventually displaced) Greek goēs (γόης), the older word for a practitioner of magic, to include astrology, alchemy and other forms of esoteric knowledge.

This association was in turn the product of the Hellenistic fascination for Pseudo-Zoroaster, who was perceived by the Greeks to be the “Chaldean” “founder” of the Magi and “inventor” of both astrology and magic.

Among the skeptical thinkers of the period, the term ‘magian’ acquired a negative connotation and was associated with tricksters and conjurers. This pejorative meaning survives in the words “magic” and “magician”.

In English, the term “magi” is most commonly used in reference to the “μάγοι” from the east who visit Jesus in Chapter 2 of the Gospel of Matthew Matthew 2:1, and are now often translated as “wise men” in English versions.

The plural “magi” entered the English language from Latin around 1200, in reference to these. The singular appears considerably later, in the late 14th century, when it was borrowed from Old French in the meaning magician together with magic.

The Magi, also referred to as the (Three) Wise Men or (Three) Kings were, in the Gospel of Matthew and Christian tradition, a group of distinguished foreigners who visited Jesus after his birth, bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

They are regular figures in traditional accounts of the nativity celebrations of Christmas and are an important part of Christian tradition.

According to Matthew, the only one of the four Canonical gospels to mention the Magi, they were the first religious figures to worship Jesus. It states that “they” came “from the east” to worship the Christ, “born King of the Jews.”

Although the account does not mention the number of people “they” or “the Magi” refers to, the three gifts has led to the widespread assumption that there were three men.

In Eastern Christianity, especially the Syriac churches, the Magi often number twelve. Their identification as kings in later Christian writings is probably linked to Psalms 72:11, “May all kings fall down before him”.

Made famous by the account of the New Testament, by which the were said to have followed a start to the birth of the Christian Messiah, the Magi were priests of the Persian empire, who were renowned throughout antiquity for their knowledge of magic, astrology and alchemy. Thus, our own word for magic refers to the occult arts of the Magi

In truth, though, the Magi known to the Greek and Roman world, were not the same as the official priests of the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, said to be founded by Zoroaster. For, when we compare the ideas that were attributed to the Magi by ancient writers, we find that they differed widely from what we know of the mainstream version of the religion, as found in its sacred scriptures, the Avesta.

Rather, it would appear that the Greeks had come into contact, not with priests of Zoroastrianism, but the notorious Magussaeans of Asia Minor, in what is now Turkey. These Magussaeans were Persian emigres that found their way to the region after it had come under Persian domination. Speaking the language of Aramaic, rather than Palahvi, they were unable to read their own scriptures in their original tongue, and thereby deviated from the faith.

Basically, the cult of the Magussaeans was a combination of heretical Zoroastrianism and Babylonian astrology. When Cyrus the Great conquered the great city of Babylon in the sixth century BC, the Magi came into contact with the teachings of the city’s astrologers, known as Chaldeans. According to Diodorus of Sicily, a Greek historian of 80 to 20 BC, and author of a universal history, Bibliotheca historica:

“…being assigned to the service of the gods they spend their entire life in study, their greatest renown being in the field of astrology. But they occupy themselves largely with soothsaying as well, making predictions about future events, and in some cases by purifications, in others by sacrifices, and in others by some other charms they attempt to effect the averting of evil things and the fulfillment of the good.

They are also skilled in the soothsaying by the flight of birds, and they give out interpretations of both dreams and portents. They also show marked ability in making divinations from the observations of the entrails of animals, deeming that in this branch they are eminently successful.”

Though astrology has often been regarded as representing an ancient form of knowledge devised by the Babylonians, scholars have now determined that its development was impossible, before the eighth century BC, due to the absence of a reliable system of chronology, and that, more properly, astrology was a product of the sixth century BC. This transformation, according to Bartel van der Waerden, was the result of the influence of Zoroastrianism, with its doctrine that the human soul originated in the stars.

In addition, the sixth century BC is also known in Jewish history as the Exile, when their entire population was located in the city, having been removed to there by Nebuchadnezzar, at the beginning of the century, after he had destroyed Jerusalem.

Having become substantial citizens, with some achieving minor administrative posts, it is possible the Jews also contributed to this development. In fact, in the Book of Daniel, Chapter 2:48, Daniel is made chief of the “wise men” of Babylon, that is of the Magi or Chaldeans. In any case, scholars have certainly recognized that the later teachings referred to collectively as the esoteric Kabbalah, seem to have been a combination of Magian and Chaldean lore.

Astrology was not a component of mainstream Zoroastrianism, and those who incorporated its concepts into their version of the faith seem to have been regarded as heretical. As Edwin Yamauchi describes, “the relationship of the Magi to Zoroaster and his teachings is a complex and controversial issue.”

Ever since the early days of the Persian Empire, there had existed an antagonism with the proponents of true Zoroastrianism and the Magi. And, according the French Assyriologist Lenormant, “to their influence are to be ascribed nearly all the changes which, towards the end of the Achaemenid dynasty, corrupted deeply the Zoroastrian faith, so that it passed into idolatry.”

The Chaldean Magi: A Library of Ancient Sources

Filed under: Uncategorized

Noratus and the famous Noratus cemetery: The largest cluster of khachkars in Armenia

Noratus (also Romanized as Noraduz) is a major and historical village in the Gegharkunik province (marz) of Armenia, near the town of Gavar.

Gegharkunik, which includes Geghama mountains and Geghama lake, presently Lake Sevan, the largest lake in the Caucasus and a major tourist attraction of the region, were named after Gegham, a Haykazuni King and fifth generation after Hayk.

Gegham was according to the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi the father of Sisak of Syunid nobles and Harmar, who was known as Arma, a descendant of the legendary patriarch of the Armenians, Hayk and the legendary Armenian hero Ara the Beautiful (also Ara the Handsome or Ara the Fair; Armenian: Ara Geghetsik).

The Siunia also known as the Siak or Syunik were a family of ancient Armenian nobles who were the first dynasty to govern as Naxarars in the Syunik Province in Armenia from the 1st century. The Naxarars were descendants of Sisak.

Inscriptions found in the region around Lake Sevan attributed to King Artaxias I confirm that in the 2nd century BC the District of Syunik constituted part of the Ancient Armenia.

Gegharkunik has an exclave inside Azerbaijan, Artsvashen, also Romanized as Artzvashen (“Eagle City” in Armenian), which came under Azerbaijani control during the Nagorno-Karabakh War and has been controlled by the Azerbaijani army since 1992.

In the Soviet times there was a branch of Haygorg (“Armenian carpet” state company) in Artsvashen. After the invasion of the Azeri forces, the residents of Artsvashen migrated to Shorzha, Vardenis, Abovyan and Chambarak, where they continued traditions of this art.

The capital of the Gegharkunik Province, Gavar, is a town in Armenia and was known as Nor Bayezet or Novyi Bayazet until 1959, then Kamo (named in honour of a Bolshevik of the same name) until 1996.

The town is situated among the high mountains of Geghama range, few miles away from the western shores of Lake Sevan, with an average height of 1982 meters above sea level. It is 91 kilometers east of the capital Yerevan.

It was founded in 1830 by Armenian migrants from the city of Bayazet (historically known as Daroink) of the Ottoman Empire. Being known as “New Bayazit”, the settlement achieved the status of a city in 1850.

However, the area of modern-day Gavar has been inhabited since the Bronze Age. Many historical tombstones, dating back to the 2nd millennium BC are founded in Gavar.

The remains of a cyclopean fort dating back to the early Iron Age, are found on a hill at the centre of the town. It is supposed that the fortress was the royal capital of the Araratian region of Velikukhi. It was surrounded with more than 22 minor fortifications.

The region of Velikukhi was conquered by the Araratian king Sarduri II. His son, Rusa II renamed the fortress in honour of Khaldi; one of the three chief deities of Ararat.

Noratus contains the famous Noraduz cemetery. The village also has a monastery and church dated to the 9th century, and a ruined basilica built by Prince Sahak.

Noratus is first mentioned as a settlement in the Middle Ages, when it was a much larger settlement. The bronze-age megalithic fort near the village points to the notion that Noratus is one of the most ancient continuously-inhabited settlements in Armenia.

Noratus cemetery is a medieval cemetery with a large number of early khachkars located in the village of Noratus, Gegharkunik marz near Gavar and Lake Sevan, 90 km north of Yerevan.

The cemetery has the largest cluster of khachkars in the republic of Armenia. It is currently the largest surviving cemetery with khachkars following the destruction of the khachkars in Old Julfa, Nakhichevan by the government of Azerbaijan.

Julfa, formerly Jugha, is the administrative capital of the Julfa Rayon administrative region of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in Azerbaijan. It is separated by the Araks River from its namesake, the town of Jolfa on the Iranian side of the border. The two towns are linked by a road bridge and a railway bridge.

Traditionally, the king of Armenia, Tigranes I, was said to have be the founder of Jugha. Existing as a village in the early Middle Ages, it grew into a town between the 10th and 13th centuries, with a population that was almost entirely Armenian.

It contained the largest surviving collection of Armenian khachkar tombstones, most dating to the 15th and 16th centuries. Between 1998 and 2006 the entire cemetery was destroyed. The various stages of the destruction process were documented by photographic and video evidence taken from the Iranian side of the border.

However, the government and state officials of Azerbaijan have denied that any destruction has taken place, stating that an Armenian cemetery never existed on the site and that Armenians have never lived in Julfa. Azerbaijan has, to date, refused to allow investigators access to the site.

The sudden and dramatic downfall of Old Julfa in the 17th century made a deep and lasting impression on Armenian society and culture. During the 19th century, poets such Hovhanness Toumanian and historians such as Ghevond Alishan produced works based on the event.

The emotions raised as a result of the destruction of the graveyard in 2006 indicates that the fate of Julfa still resonates within contemporary Armenian society.

Filed under: Uncategorized

The forerunners of Gothic architecture are of Armenian origin

Gothic is an extinct Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other languages such as Portuguese, Spanish and French.

As a Germanic language, Gothic is a part of the Indo-European language family. It is the earliest Germanic language that is attested in any sizable texts, but lacks any modern descendants. The oldest documents in Gothic date back to the 4th century.

The language was in decline by the mid-6th century, due, in part, to the military defeat of the Goths at the hands of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation (in Spain the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted to Catholicism in 589).

The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) as late as the 8th century, and in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea apparently as late as the early 9th century. Gothic-seeming terms found in later (post-9th century) manuscripts may not belong to the same language.

Crimean Gothic was a Gothic dialect spoken by the Crimean Goths in some isolated locations in Crimea until the late 18th century. The existence of a Germanic dialect in the Crimea is attested in a number of sources from the 9th century to the 18th century.

However, only a single source provides any details of the language itself: a letter by the Flemish ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, dated 1562 and first published in 1589, gives a list of some eighty words and a song supposedly in the language.

Busbecq’s information is problematic in a number of ways: his informants were not unimpeachable (one was a Greek speaker who knew Crimean Gothic as a second language, the other a Goth who had abandoned his native language in favour of Greek); there is the possibility that Busbecq’s transcription was influenced by his own language (a Flemish dialect of Dutch); there are undoubted misprints in the printed text, which is the only source.

Nonetheless, much of the vocabulary cited by Busbecq is unmistakably Germanic.

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture.

Originating in 12th-century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as Opus Francigenum (“French work”) with the term Gothic first appearing during the latter part of the Renaissance. Its characteristics include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault and the flying buttress.

Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe. It is also the architecture of many castles, palaces, town halls, guild halls, universities and to a less prominent extent, private dwellings.

It is in the great churches and cathedrals and in a number of civic buildings that the Gothic style was expressed most powerfully, its characteristics lending themselves to appeals to the emotions, whether springing from faith or from civic pride.

A great number of ecclesiastical buildings remain from this period, of which even the smallest are often structures of architectural distinction while many of the larger churches are considered priceless works of art and are listed with UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. For this reason a study of Gothic architecture is largely a study of cathedrals and churches.

A series of Gothic revivals began in mid-18th-century England, spread through 19th-century Europe and continued, largely for ecclesiastical and university structures, into the 20th century.

The forerunners of Gothic architecture are of Armenian origin

In 933, The fortress-city of Kars was proclaimed as the new capital. Finally in 961, the capital of Armenia was proclaimed the City of Ani, which would become one of the greatest cities in Armenian history. The city at its height had nearly 200,000 inhabitants and was one of the largest of its era. This was at a time, when many of the current European capitals, including London and Paris, were relatively small, compared to that of Ani, which later on due to the number of many splendid churches was dubbed as “the city of 1001 churches.”

Josef Strzygowski, the renowned Austrian art historian, in his magnum opus, The Architecture of Armenia and Europe, outlined the influence of Armenian art and architecture upon Europe, including upon early Medieval architecture of Europe. Strzygowski was amongst the first to point out early Gothic styles that were applied in Armenian architecture of Ani and elsewhere which later on were transmuted to Europe by Armenian architects, many of whom were personally employed by a number of European kings.

Trdat the Architect (circa 940s – 1020; Latin: Tiridates) was the chief architect of the Bagratuni kings of Armenia, whose 10th century monuments are the forerunners of Gothic architecture which came to Europe several centuries later.

The belltower at Haghpat Monastery

After a great earthquake in 989 ruined the dome of Aya (Hagia) Sophia, the Byzantine officials summoned Trdat to Byzantium to organize repairs. The restored dome was completed by 994. Trdat is also thought to have designed or supervised the construction of Surb Nshan (Holy Sign, completed in 991), the oldest structure at Haghpat Monastery.

Even [Hagia] Aya Sophia, the cathedral, was torn to pieces from top to bottom. On account of this, many skillful workers among the Greeks tried repeatedly to reconstruct it. The architect and stonemason Trdat of the Armenians also happened to be there, presented a plan, and with wise understanding prepared a model, and began to undertake the initial construction, so that [the church] was rebuilt more handsomely than before.

Ani Cathedral moder by Toros Toramanian

In 961, Ashot III moved his capital from Kars to the great city of Ani where he assembled new palaces and rebuilt the walls. The Catholicosate was moved to the Argina district in the suburbs of Ani where Trdat completed the building of the Catholicosal palace and the Mother Cathedral of Ani. This cathedral offers an example of a cruciform domed church within a rectangular plan.

Ani

The cruciform domed church, or the cross inscribed in a rectangle, was not frequently used in the following centuries; we have, however, an outstanding example in the cathedral of Ani, built by the architect Trdat between the years 989 and 1001.

The side apses are almost entirely screened by short walls, as at Mren and St. Gayane, but the dome, instead of being placed over the middle of the rectangular space created by these short walls and the west wall, is brought closer to the main apse. From the powerful, clustered piers rise pointed and stepped arches supporting the dome on pendentives. Recessed pilasters are placed against the north and south walls, facing the clustered piers. Ten small semi-circular niches open into the main apse wall.

The clustered piers, the pointed arches and vaults, which had also been used by Trdat in the churches of Argin and Horomos, remind one of early Gothic architecture, but these forms appear in Armenia about a hundred years before they come into use in Western Europe.

Though of moderate size, the cathedral of Ani is imposing in the interior through the harmony of the proportions. The blind arcade with slender columns and ornate arches, the delicate interlaces carved around the door and windows add to the beauty of the exterior, and this church deserves to be listed among the important examples of medieval architecture.

The forerunners of Gothic architecture are of Armenian origin

Filed under: Uncategorized

The Arabs and the Nabateans of Petra

Petra is a historical and archaeological city in the southern Jordanian governorate of Ma’an that is famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit system. Another name for Petra is the Rose City due to the color of the stone out of which it is carved.

It lies on the slope of Jebel al-Madhbah (identified by some as the biblical Mount Hor) in a basin among the mountains which form the eastern flank of Arabah (Wadi Araba), the large valley running from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba.

It was first established sometime around the 6th century BC, by the Nabataean Arabs, a nomadic tribe who settled in the area and laid the foundations of a commercial empire that extended into Syria. It was established possibly as the capital city of the Nabataeans as early as 312 BC.

Despite successive attempts by the Seleucid king Antigonus, the Roman emperor Pompey and Herod the Great to bring Petra under the control of their respective empires, Petra remained largely in Nabataean hands until around 100AD, when the Romans took over.

It was still inhabited during the Byzantine period, when the former Roman Empire moved its focus east to Constantinople, but declined in importance thereafter. The Crusaders constructed a fort there in the 12th century, but soon withdrew, leaving Petra to the local people until the early 19th century, when it was rediscovered by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812.

Petra is today a symbol of Jordan, as well as Jordan’s most-visited tourist attraction. It was described as “a rose-red city half as old as time” in a Newdigate Prize-winning poem by John William Burgon, and was chosen by the Smithsonian Magazine as one of the “28 Places to See Before You Die.”

Petra has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985. UNESCO has described it as “one of the most precious cultural properties of man’s cultural heritage”.

The Nabataeans, also Nabateans, were an ancient people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, their settlements in CE 37 – c. 100, gave the name of Nabatene to the borderland between Arabia and Syria, from the Euphrates to the Red Sea.

Located between the Sinai Peninsula and the Arabian Peninsula, its northern neighbour was the kingdom of Judea, and its south western neighbour was Ptolemaic Egypt. Its capital was the city of Petra in Jordan, and it included the towns of Bostra, Mada’in Saleh, and Nitzana.

Petra was a wealthy trading town, located at a convergence of several important trade routes. One of them was the Incense Route which was based around the production of both myrrh and frankincense in southern Arabia, and ran through Mada’in Saleh to Petra. From here the aromatics were distributed throughout the Mediterranean region.

Diodorus Siculus (book ii) described them as a strong tribe of some 10,000 warriors, pre-eminent among the nomads of Arabia, eschewing agriculture, fixed houses, and the use of wine, but adding to pastoral pursuits a profitable trade with the seaports in frankincense, myrrh and spices from Arabia Felix (today’s Yemen), as well as a trade with Egypt in bitumen from the Dead Sea.

Onomastic analysis has suggested that Nabataean culture may have had multiple influences. Classical references to the Nabataeans begin with Diodorus Siculus; they suggest that the Nabataeans’ trade routes and the origins of their goods were regarded as trade secrets, and disguised in tales that should have strained outsiders’ credulity.

Their loosely-controlled trading network centered on strings of oases that they controlled, where agriculture was intensively practiced in limited areas, and on the routes that linked them, had no securely defined boundaries in the surrounding desert.

Trajan conquered the Nabataean kingdom, annexing it to the Roman Empire, where their individual culture, easily identified by their characteristic finely-potted painted ceramics, became dispersed in the general Greco-Roman culture and was eventually lost.

The brief Babylonian captivity of the Hebrews that began in 586 BCE opened a minor power vacuum in Judah (prior to the Israelites’ return under the Persian King, Cyrus the Great), and as Edomites moved into open Judaean grazing lands, Nabataean inscriptions began to be left in Edomite territory.

The first definite appearance was in 312/311 BCE, when they were attacked at Sela or perhaps Petra without success by Antigonus I’s officer Athenaeus as part of the Third War of the Diadochi; at that time Hieronymus of Cardia, a Seleucid officer, mentioned the Nabataeans in a battle report.

About 50 BCE, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus cited Hieronymus in his report, and added the following: “Just as the Seleucids had tried to subdue them, so the Romans made several attempts to get their hands on that lucrative trade.”

The Nabataeans had already some tincture of foreign culture when they first appear in history. The language of the Nabataean inscriptions, attested from the 2nd century BCE, shows a local development of the Aramaic language, which had ceased to have super-regional importance after the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire (330 BC). The Nabataean alphabet itself also developed out of the Aramaic alphabet.

That culture was Aramaic; they wrote a letter to Antigonus in Syriac letters, and Aramaic continued to be the language of their coins and inscriptions when the tribe grew into a kingdom, and profited by the decay of the Seleucids to extend its borders northward over the more fertile country east of the Jordan.

They occupied Hauran, and in about 85 BC their king Aretas III became lord of Damascus and Coele-Syria. Nabataeans became the Arabic name for Aramaeans, whether in Syria or Iraq, a fact which was thought to show that the Nabataeans were originally Aramaean immigrants from Babylonia.

Proper names on their inscriptions suggest that they were ethnically Arabs who had come under Aramaic influence. Starcky identifies the Nabatu of southern Arabia (Pre-Khalan migration) as their ancestors. However different groups amongst the Nabataeans wrote their names in slightly different ways, consequently archeologists are reluctant to say that they were all the same tribe, or that any one group is the original Nabataeans.

Various native homelands were suggested for the Nabataeans, such as Northern Arabia and the North-East of the Arabian peninsula, based on a probable similarity between the names of deities which were worshiped in those areas, and some similarities between the inscriptions of some other Arab groups who inhabited the southern half of ancient Mesopotamia.

In 1997, a group of scholars of the University of Exeter in England made a critical review of all these theories in a multi-volume study, arguing that the original homeland of Nabataens was to the south of Al Jawf Province, a region of Saudi Arabia, located in the north of the country, bordering Jordan.

This Aramaic dialect was increasingly affected by the Arabic dialect of the local population. From the 4th century, the Arabic influence becomes overwhelming, in a way that it may be said the Nabataean language shifted seamlessly from Aramaic to Arabic.

The Arabic alphabet itself developed out of cursive variants of the Nabataean script in the 5th century, and Ibn Wahshiyya claimed to have translated from this language in his Nabataean corpus.

Pre-Islamic religion – Allah

Allah is the Arabic word for God (literally ‘the God’, as the initial “Al-” is the definite article). It is used mainly by Muslims to refer to God in Islam, Arab Christians, and often, albeit not exclusively, by Bahá’ís, Arabic-speakers, Indonesian and Maltese Christians, and Mizrahi Jews. Christians and Sikhs in Malaysia also use and have used the word to refer to God.

The term Allāh is derived from a contraction of the Arabic definite article al- “the” and ilāh “deity, god” to al-lāh meaning “the [sole] deity, God”. Cognates of the name “Allāh” exist in other Semitic languages, including Hebrew and Aramaic.

The name was previously used by pagan Meccans as a reference to a creator deity, possibly the supreme deity in pre-Islamic Arabia. In pre-Islamic Arabia amongst pagan Arabs, Allah was not considered the sole divinity, having associates and companions, sons and daughters–a concept that was deleted under the process of Islamization.

The name Allah was used by Nabataeans in compound names, and was found throughout the entire region of the Nabataean kingdom. From Nabataean inscriptions, Allah seems to have been regarded as a “High and Main God”, while other deities were considered to be mediators before Allah and of a second status, which was the same case of the worshipers at the Kaaba temple at Mecca.

Many inscriptions containing the name Allah have been discovered in Northern and Southern Arabia as early as the 5th century B.C., including Lihyanitic, Thamudic and South Arabian inscriptions.

The name Allah or Alla was found in the Epic of Atrahasis engraved on several tablets dating back to around 1700 BC in Babylon, which showed that he was being worshipped as a high deity among other gods who were considered to be his brothers but taking orders from him.

Dumuzid the Shepherd, a king of the 1st Dynasty of Uruk named on the Sumerian King List, was later over-venerated so that people started associating him with “Alla” and the Babylonian god Tammuz.

Enki is a god in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. Enki/Ea is essentially a god of civilization, wisdom, and culture. He was also the creator and protector of man, and of the world in general. He was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation (Nudimmud: nu, likeness, dim mud, make beer).

He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, an ancient Sumerian city in what is now Tell Abu Shahrain, Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq, long considered the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

As Ea, Enki had a wide influence outside of Sumer, being equated with El (at Ugarit) and possibly Yah (at Ebla) in the Canaanite ‘ilhm pantheon, he is also found in Hurrian and Hittite mythology, as a god of contracts, and is particularly favourable to humankind.

A large number of myths about Enki have been collected from many sites, stretching from Southern Iraq to the Levantine coast. He figures in the earliest extant cuneiform inscriptions throughout the region and was prominent from the third millennium down to Hellenistic times.

He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki.

Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40,” occasionally referred to as his “sacred number.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water.” In Sumerian E-A means “the house of water”, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

The pool of the Abzu at the front of his temple was adopted also at the temple to Nanna (Akkadian Sin) the Moon, at Ur, and spread from there throughout the Middle East. It is believed to remain today as the sacred pool at Mosques, or as the holy water font in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael), with Ia. Jean Bottero (1952) and others suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea, Enki’s Akkadian name, associating the Canaanite theonym Yahu, and ultimately Hebrew YHWH.

This hypothesis is dismissed by some scholars as erroneous, based on a mistaken cuneiform reading, but academic debate continues. Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic Yamm (sea), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw, or Ya’a.

Pre-Islamic religion

Allāt, Al-Uzzá and Manāt was three chief goddesses of Arabian religion in pre-Islamic times and was worshiped as the daughters of Allah by the pre-Islamic Arabs. They were goddesses of Mecca.

Allat is an alternative name of the Mesopotamian goddess of the underworld, now usually known as Ereshkigal. She was reportedly also venerated in Carthage under the name Allatu.

The goddess occurs in early Safaitic graffiti (Safaitic han-’Ilāt “the Goddess”) and the Nabataeans of Petra and the people of Hatra also worshipped her, equating her with the Greek Athena and Tyche and the Roman Minerva.

She is frequently called “the Great Goddess” in Greek in multi-lingual inscriptions. According to Wellhausen, the Nabataeans believed al-Lāt was the mother of Hubal (and hence the mother-in-law of Manāt).

The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, considered her the equivalent of Aphrodite: The Assyrians call Aphrodite Mylitta, the Arabians Alilat, and the Persians Mitra. In addition that deity is associated with the Indian deity Mitra.

This passage is linguistically significant as the first clear attestation of an Arabic word, with the diagnostically Arabic article al-. The Persian and Indian deities were developed from the Proto-Indo-Iranian deity known as Mitra.

According to Herodotus, the ancient Arabians believed in only two gods: They believe in no other gods except Dionysus and the Heavenly Aphrodite; and they say that they wear their hair as Dionysus does his, cutting it round the head and shaving the temples. They call Dionysus, Orotalt; and Aphrodite, Alilat.

The first known mention of al-‘Uzzá is from the inscriptions at Dedan, the capital of the Lihyanite Kingdom, an Ancient Northwest Arabian kingdom in the fourth or third century BC. A stone cube at aṭ-Ṭā’if (near Mecca) was held sacred as part of her cult. Al-‘Uzzá, like Hubal, was called upon for protection by the pre-Islamic Quraysh.

Al-‘Uzzá was also worshipped by the Nabataeans, who equated her with the Greek goddess Aphrodite Ourania (Roman Venus Caelestis). She had been adopted alongside Dushara as the presiding goddess at Petra, the Nabataen capital, where she assimilated with Isis, Tyche, and Aphrodite attributes and superseded her sisters.

Manāt was one of the three chief goddesses of Mecca. The pre-Islamic Arabs believed Manāt to be the goddess of fate. She was known by the cognate name Manawat to the Nabataeans of Petra, who equated her with the Graeco-Roman goddess Nemesis, and she was considered the wife of Hubal.

According to Grunebaum in Classical Islam, the Arabic name of Manat is the linguistic counterpart of the Hellenistic Tyche, Dahr, fateful ‘Time’ who snatches men away and robs their existence of purpose and value. There are also connections with Chronos of Mithraism and Zurvan mythology.

Dushara, (“Lord of the Mountain”), also transliterated as Dusares, a deity in the ancient Middle East worshipped by the Nabataeans at Petra and Madain Saleh (of which city he was the patron). He was mothered by Manat the goddess of fate.

In Greek times, he was associated with Zeus because he was the chief of the Nabataean pantheon as well as with Dionysus. His sanctuary at Petra contained a great temple in which a large cubical stone was the centrepiece.

Chaabou (perhaps the original version of the Arabic word Ka’bah) is one of the goddesses in the Nabataean Pantheon, as noted by Epiphanius of Salamis (c.315–403). The description points to either Allat or Uzza, but is most likely the former, since Allat is also associated with Aphrodite, a fertility goddess.

According to Epiphanius, Chaabou was a virgin that gave birth to Dusares (aka Dhu Sharaa, and DVSARI), the ‘Lord of Mount Seir’, the god of the Nabataeans who was equated with Zeus. Epiphanius records a festival celebrating the birth of Dusares on the 25th of December whereby the Black Stone of Dusares (considered newly born) is carried around the courtyard of the temple seven times.

Remnants of this practice are observed not only in the present-day Muslim Hajj, but also in most Arab countries where, upon birth of a child, the family carries the baby around the house seven times.

This ritual is called Subu’ (meaning ‘the sevens’). It is also interesting that once the pilgrims return from the Hajj, they are considered as those who have been purified from sin, as if they were newly born.

John of Damascus, in his accounts regarding the Hagarenes or Saracens, noted that they revered a certain black stone and showered it with kisses, and that it was the head of Aphrodite, the goddess that they once worshipped and whom they called Chobar in their language.

Hagarenes, is a term that widely used by early Syriac, Greek, Coptic and Armenian sources to describe the early Arab conquerors of Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

The name was used in Judeo-Christian literature and Byzantine chronicles for “Hanif” Arabs, refering to one who maintained the pure monothestic beliefs of the patriarch Ibrahim during the period known as the Pre-Islamic period or Age of Ignorance, and later for Islamic forces as a synonym of the term Saracens.

The Syriac term “Hagraye” can be roughly translated as “the followers or descendants of Hagar”, while the other frequent name, “Mhaggraye”, is thought to have connections with the Arabic “Muhajir”, other scholars assume that the terms may not be of Judeo-Christian origin.

Hagar, meaning “uncertain”, is a biblical person in the Book of Genesis Chapter 16. She was an Egyptian handmaid of Sarai (Sarah), who gave her to Abram (Abraham) to bear a child. Thus came the firstborn, Ishmael, the patriarch of the Ishmaelites.

The name Hagar originates from the Book of Genesis, is mentioned in Hadith, and alluded to in the Qur’an. She is revered in the Islamic faith and acknowledged in all Abrahamic faiths. In mainstream Christianity, she is considered a concubine to Abram.

Pre-Islamic religion – The end

The “Hijra”, also Hijrat or Hegira, is the migration or journey of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina between June 21 and July 2 in 622 CE.

The shrine and temple dedicated to al-Lat, who was then known as “the lady of Tā’if, in Taif, about 100 km (62 mi) southeast of Mecca, was demolished along with all of the other signs of the city’s previously pagan existence on the orders of Muhammad, during the Expedition of Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, in the same year as the Battle of Tabuk (which occurred in October 630 AD).

The destruction of the idol was a demand by Muhammad before any reconciliation could take place with the citizens of Taif who were under constant attack and suffering from a blockade by the Banu Hawazin, led by Malik, a convert to Islam who promised to continue the war against the citizens of the city which was started by Muhammad in the Siege of Taif.

Both Ta’if and Mecca were resorts of pilgrimage. Ta’if was more pleasantly situated than Mecca itself and the people of Ta’if had close trade relations with the people of Mecca. The people of Ta’if carried on agriculture and fruit‑growing in addition to their trade activities.

During the 5th century Christianity became the prominent religion of the region following conquest by Barsauma.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Soma among the Armenians

Soma was a god, a plant, and an intoxicating beverage. It is referenced in some 120 of 1028 verses of the Indian Rig Veda (mid second millenium BC.). Haoma was its Iranian counterpart. Although the Iranian Avesta mentions haoma less frequently, there is little doubt that the substances were similar or identical. In both India and Iran, at some point the true identity of soma/haoma was forgotten, and substitutes for it were adopted.

It has been suggested that abandonment of the divine entheogen and its replacement by surrogates occurred because the original substance was no longer available or was difficult to obtain once the proto Indo-Iranians left their “original homeland” and emigrated.

During the past two hundred years, scholars have tried with varying degrees of success to identify this mysterious plant which was at the base of early Indo-Iranian worship. As early as 1794, Sir William Jones suggested that haoma was “a species of mountain rue”, or Peganum harmala L. (Arm. spand). Other soma candidates in the 19th and early 20th centuries have included cannabis (Arm. kanep’) and henbane (Arm. aghueshbank).

All of these plants are native to the Armenian highlands, and all of them were used by the Armenians and their predecessors for medicinal and magico-religious purposes. If the divine elixir really was a single substance rather than a mixture, then, in our view, none of the above-mentioned nominees alone qualifies.

The pharmacological effects of Peganum harmala, cannabis, or henbane, taken alone, simply do not match the Vedic and Iranian descriptions of the effects of soma/haoma. In the 1960s, R. Gordon Wasson proposed a new candidate, whose effects are more consistent with those mentioned in the Vedas. The present study will examine Wasson’s thesis and look for supporting evidence in ancient Armenian legends and customs.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Phrygian Cult Practice

In a society where there were no sacred texts or established doctrines that we can use to understand religious practice, our knowledge of Phrygian religion comes almost entirely from the physical remains of cult rituals: the representations of deities, votive offerings to them, and the sanctuaries and sacred spaces of the Phrygians.

Our limited knowledge of the Phrygian language means that we do not know what the Phrygians thought about the divine, nor can we be certain about the nature of their religious practices.

Greek and Roman historical and literary texts give a vivid picture of Phrygian rites, but a better understanding of Phrygian cult practice can be gained from the evidence within Phrygia itself. This discussion will be primarily concerned with Phrygian cult material and its meaning in the context of Phrygian society.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Mithras – The Other Saviour

The Eurocentric viewer of modern life may take the underlying mythology of western calendar myths for granted, assuming that, for instance, the winter solstice holiday is basically either about the birth of the Christian god-man Jesus, or about a jolly fat elf who lives at the North Pole and brings toys to good children on 24 December.

This same observer may be startled to discover that the origins of many of the beliefs and customs surrounding the celebration of the solstice holiday – both relating to Jesus and Santa Claus – have their roots in quite a different saviour god who brought blessings to mankind – the now almost-forgotten god Mithras.

The cult of Mithras, which flourished from Britain to Palestine in the early centuries of the First Millennium AD, has left us a legacy of winter customs, a number of intriguing archaeological sites, and a strange cult figure in a funny hat. The Roman army bathed in bulls’ blood and called one another ‘brother’ in his name, and poets from TaliesinMithras – The Other Saviour

Filed under: Uncategorized

Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

This paper discusses forms of a ‘Great Mother’ goddess as she evolved in prehistoric and early historic Anatolia, her movements throughout Asia Minor, her transmission to Greece and Rome, and her worship thence throughout the ancient world. It also addresses the controversy of how and whether the Phrygian and later Greco-Roman goddess Cybele is connected to the Anatolian Kubaba mentioned in Hittite texts and later worshipped in Carchemish.

Through my translations of Hittite, Phrygian, Greek and Roman texts I try to explicate the relationship of the Anatolian Kubaba and Phrygian, Greek, and Roman Cybele.

In pre-Neolithic and Neolithic Anatolia there were several cultures to which belong female figurines associated with felines. The earliest carved on rock in an area between pillars containing depictions of felines. The double mound of Çatal höyük, 45 kilometers south of modern Konya, dates from the eighth to the sixth millennia BC.

…

Although the Kybileian Mountain Mother may not be related linguistically to the earlier Kubaba, the iconography of female figure, feline, throne, and mural crown links Kubaba to the Hittite Great Goddess, the sun-goddess of Arinna, or Hebat, depicted as a Mistress of Animals and as mother of the gods; the feline links her to several pre historic cultures of Anatolia. Thus there is continuity of a “Great Mother” figure accompanied by lions from pre-Neolithic Anatolia through the first centuries of this era.

Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

Ancient Felines and the Great-Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

Filed under: Uncategorized

Day of Wrath

“Stéphane Hessel at a pro-Palestinian rally. He is wearing a Phrygian cap, an icon of the French Revolution.”

Mher remains entombed in Raven’s Rock since justice still doesn’t reign over the earth, but someday Mher will come out of the cave, mounted on his fiery horse, to punish the enemies of his people. That will be the Day of Wrath.

Filed under: Uncategorized

The Midas Touch

MUSHKI – ARMENO-PHRYGIAN

The Mushki were an Iron Age people of Anatolia, known from Assyrian sources. They do not appear in Hittite records. Assyrian sources identify the Western Mushki with the Phrygians, while Greek sources clearly distinguish between Phrygians and Moschoi.

Two different groups are called Muški in the Assyrian sources, one from the 12th to 9th centuries, located near the confluence of the Arsanias and the Euphrates (“Eastern Mushki”), and the other in the 8th to 7th centuries, located in Cappadocia and Cilicia (“Western Mushki”).

Identification of the Eastern with the Western Mushki is uncertain, but it is of course possible to assume a migration of at least part of the Eastern Mushki to Cilicia in the course of the 10th to 8th centuries.

The Eastern Muski appear to have moved into Hatti in the 12th century, completing the downfall of the collapsing Hittite state, along with various Sea Peoples. They established themselves in a post-Hittite kingdom in Cappadocia.

Whether they moved into the core Hittite areas from the east or west has been a matter of some discussion by historians. Some speculate that they may have originally occupied a territory in the area of Urartu; alternatively, ancient accounts suggest that they first arrived from a homeland in the west (as part of the Armeno-Phrygian migration), from the region of Troy, or even from as far as Macedonia, as the Bryges.

Armeno-Phrygian is a term for a minority supported claim of hypothetical people who are thought to have lived in the Armenian Highland as a group and then have separated to form the Phrygians and the Mushki of Cappadocia.

It is also used for the language they are assumed to have spoken. It can also be used for a language branch including these languages, a branch of the Indo-European family or a sub-branch of the proposed Graeco-Armeno-Aryan or Armeno-Aryan branch.

Classification is difficult because little is known of Phrygian and virtually nothing of Mushki, while Proto-Armenian forms a subgroup with Hurro-Urartian, Greek, and Indo-Iranian. These subgroups are all Indo-European, with the exception of Hurro-Urartian.

Note that the name Mushki is applied to different peoples by different sources and at different times. It can mean the Phrygians (in Assyrian sources) or Proto-Armenians as well as the Mushki of Cappadocia, or all three, in which case it is synonymous with Armeno-Phrygian.

The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture notes that “the Armenians according to Diakonoff, are then an amalgam of the Hurrian (and Urartians), Luvians and the Proto-Armenian Mushki (or Armeno-Phrygians) who carried their IE language eastwards across Anatolia.”

MIDAS

Midas is the name of at least three members of the royal house of Phrygia. The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ability to turn everything he touched with his hand into gold. This came to be called the Golden touch, or the Midas touch.

The Phrygian city Midaeum was presumably named after this Midas, and this is probably also the Midas that according to Pausanias founded Ancyra. According to Aristotle, legend held that Midas died of starvation as a result of his “vain prayer” for the gold touch.

The legends told about this Midas and his father Gordias, credited with founding the Phrygian capital city Gordium and tying the Gordian Knot, indicate that they were believed to have lived sometime in the 2nd millennium BC, well before the Trojan War. However, Homer does not mention Midas or Gordias, while instead mentioning two other famed Phrygian kings, Mygdon and Otreus.

HUBAL

Hubal was a god worshipped in pre-Islamic Arabia, notably at the Kaaba in Mecca. His idol was a human figure, believed to control acts of divination, which was in the form of tossing arrows before the statue. The direction in which the arrows pointed answered questions asked of the idol.

The origins of the cult of Hubal are uncertain, but the name is found in inscriptions from Nabataea in northern Arabia (across the territory of modern Syria and Iraq). The specific powers and identity attributed to Hubal are equally unclear.

Hubal most prominently appears at Mecca, where an image of him was worshipped at the Kaaba. According to Karen Armstrong, the sanctuary was dedicated to Hubal, who was worshipped as the greatest of the 360 idols the Kaaba contained, which probably represented the days of the year.

Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi’s Book of Idols describes the image as shaped like a human, with the right hand broken off and replaced with a golden hand. According to Ibn Al-Kalbi, the image was made of red agate, whereas Al-Azraqi, an early Islamic commentator, described it as of “cornelian pearl”.

Al-Azraqi also relates that it “had a vault for the sacrifice” and that the offering consisted of a hundred camels. Both authors speak of seven arrows, placed before the image, which were cast for divination, in cases of death, virginity and marriage.

Access to the idol was controlled by the Quraysh tribe. The god’s devotees fought against followers of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad during the Battle of Badr in 624 CE. After Muhammad entered Mecca in 630 CE, he removed the statue of Hubal from the Kaaba along with the idols of all the other pagan gods.

Filed under: Uncategorized

A false flag – False FB profile – Provocations

Houda Ezra Ebrahim Nonoo, Bahrain’s Jewish U.S. ambassador

One of Bahrain’s 36 Jews, Nonoo says she has never been discriminated against in her country, where woman are allowed to vote, choose to wear a headscarf and even drive.

Her statement:

I can’t wait for that day when its done!!!

we will never stab in your backs, when we want to do something we tell ppl before doing it.. Israel is here to exist and all that promised land belongs to the Jewish ppl, either u like it or not…

G-d promised us all this land and it is written in the Bible. People rejecting Bible are rejecting G-d’s words. Even Christians are also agree with this map. I suggest muslims to follow G-ds words.

muslim terrorist from arabia occupied Israel and named it palestine, so we took out land back – like muslims want to occupy europe today - I want the muslims to accept this truth as soon as possible when they see this they will be used to it and accept it, accept it sooner so better.

Call what ever you like to call it but this is not going anywhere, Israel is here to stay and Israel will get its land back.

Everyday we remember and remind our children about how big and far our promised land is when we see the map of our promised land on our currency. So you ppl can just f..k off.

But then:

While you fools are smelling and tasting my shit and guessing if its real Israeli or not so I have said what I meant and what we believe in, the promised land belongs to Jewish people, either u fools like it or not so it remains your problem.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Vår bakgrunn

Dette for å vise til vår sivilisasjons røtter, vår bakgrunn og eksistens. Vi lever på denne jordkloden – og den er viktig – må bevares! – ingen krig, urett eller forurensing. Vi er på feil løp og vil tape mot de eksistensielle kreftene. Gudene er naturkrefter, de som lager vilkårene for vår eksistens. Den menneskelige familie er viktig for det er vår kroppslige eksistens – vi trenger denne for å utvikle denne planeten.

SKRIK!!!!!!

- Syrias barn skriker

Kanskje de destruktive kreftene i dag oppererer fra USA, men de er inne i oss alle – og de er en del av oss – vi må bare beherske dem!

Vredens dag kommer nærmere!

Vi meve ut fra nestekjærlighetsprinsippet!

- for hat vil møte mørke og nestekjærlighet vil møte lys!

Du må ikke sitte trygt i ditt hjem

og si: Det er sørgelig, stakkars dem!

Du må ikke tåle så inderlig vel

den urett som ikke rammer dig selv!

Jeg roper med siste pust av min stemme:

Du har ikke lov til å gå der og glemme!

A Resistance Hero Fires Up the French

-

-

-

Vi meve ut fra nestekjærlighetsprinsippet

- for hat vil møte mørke og nestekjærlighet vil møte lys!

Å dyrke Maria (Ma-ri-a) – Mariannu (Maria-nnu) er ikke avgudsdyrkelse. Jesus er Mitra (Mi-ta-nni) og Maria er Ma-ri-a-nnu. Marianne er frigjøringskvinnen i Frankrike, hvor også den frygisk-armenske frigjøringslua står høyt i hevd.

Hurrierne, også kjent som arierne, utgjør bakgrunnen for vår histire, være seg som kaukasere, indoeuropeere eller semitter. De synes å være spesielt i slekt med nakh språkene innen den nordøstkaukasiske språkfamilien og med haplogruppe J2, samt med sumererne i det sørlige Mesopotamia.

Det meste av hurriernes oppkonstruerte historie stammer fra dokumenter funnet i bibliotekene til andre av tidens folk, inkludert hettitene, akkaderne, sumererne og egypterne. Men alt tyder på at alle disse folkene hadde sine røtter fra hurrierne, som synes å ha vært til stede i den transkaukasiske regionen siden tidenes morgen, så på tross for at deres opprinnelse ikke er kjent så peker alt på at deres hjemland lå et sted i den transkaukasiske regionen.

En av kontroversene dreier seg om forholdet mellom indo-arierne og hurrierne, hvor av noen hevder at hurrisk var indo-ariere, eller nærmere bestemt proto indo-europeere, mens andre hevder at også indo-arierne migrerte fra den transkaukasiske regionen og bosatte seg i de samme regionene som hurrierne nosatte seg slik at hurriernes ble influert av indo-arierne og adopterte deres språktrekk.

Mye tyder på at indoeuropeerne er i slekt med de kaukasiske språkene, nærmere bestemt de nordvest kaukasiske språkene, og dermed med adhyge befolkningen, også kjent som sirkasserne, og dermed med haplogruppe G, som var en av de første befolkningene som utviklet jordbruk i Sørvest Asia. Spørsmålet blir da om de nordvest og nordøst kaukasiske språkene er beslektet, og om hurro-urartisk kan være moderspråket til de alle tre.

Grunnlaget for det armenske språket er ennå uklart, men alt tyder på at det er det eldste indoeuropeiske språket og det stammer fra den transkaukasiske regionen, samt at det enten stammer fra det hurro-urartiske språket eller i det minste at de to befolkningene har har levd i en lang periode med bilingvisme, slik at armensk er det språket som tales i dag som er de hurro-urartiske språkene nærmest.

Uansett så stammer den indoeuropeiske kulturen fra den transkaukasiske regionen og deler opphev med både hurrierne, sumererne og med semittene. Kura Arakses kulturen, som selv synes å ha bakgrunn i Tell Halaf og Tell Hassuna i det sørlige Kaukasus, samt Majkop kulturen, som noe senere oppsto i det nordlige Kaukasus, synes å være hovedfaktoren når det kommer til indoeuropeernes ekspansjon ut på steppene.

Uansett ble hurriernes territorium etter hvert bebodd av semittiske og indoeuropeiske folk, som blandet seg med dem og bevarte deres kulturelle trekk. Uansett ble hurrierne til tider sterkere og kom sammen med indoariere til å danne Mittani kongedømmet omkring 1600 f.vt.

Mitanniriket ble referert til som Maryannu, nhrn, som blir uttalt Naharin fra det assyrisk-akkadisk ordet for elv, som i Aram-Naharaim, eller Mitanni av egypterne, Hurri (Ḫu-ur-ri) av hettittene (he-ti, utledet fra ha-tu), lokalisert i nordøstlige Syria, og Hanigalbat (Han-i-gal-bat) av assyrerne. Ulike navn synes å ha blitt om hverandre for det samme kongeriket.

Armenerne het hurriere, som vil si ariere, fra det armenske ordet hur/hurri, som betyr ild/guddommelig og blir nevnt i assyriske og armensk-sumeriske kilder som dateres til bronsealderen. På armensk er ordet hurri/hur en variant av ar/har/hur, noe som forbinder hurriere (Urartu) med armener-ariere.

Aram-Naharaim er en region som blir nevnt 5 ganger i Gamletestamentet, og som blir identifisert med Nahrima, som blir nevnt i tre tavler av Amarna korrespondansen som en geografisk beskrivelse på Mitanni, hvor Abraham ifølge Genesis stammer fra (Gen 24:4) og hvor Avrams bror Nachor levde (Gen.24:10), men som noen steder skiftes ut med Paddam aram og Haran. I assyriske kilder nevnes Uruatri (Urartu) som et navn på en føderasjon som inkluderte landet Nairi.

De tidligste nedtegnelser av Harran kommer fra Eblatavlene fra rundt 2300 f.vt. Fra disse er det kjent at en tidlig konge eller høvding i Harran hadde giftet seg med en prinsesse fra Ebla som deretter ble kjent som “dronning av Harran”, og hennes navn opptrer på en rekke dokumenter. Det synes som om Harran forble en del av det regionale kongedømmet Ebla i en del tid etter.

Aleppo har nesten ikke blitt berørt av arkeologer i moderne tid ettersom den nye byen ligger oppå den gamle, men byen har vært bebodd fra omkring 5000 f.vt. Aleppo, som betyr lys, eller belyst, og er det samme som arev, som betyr sol på armensk, fra tidlig av en mye viktigere by enn Damaskus. Fra det tredje årtusen er Aleppo hovedstaden i et uavhengig rike nært forbundet med Ebla, kjent som Armi for Ebla og Arman for akkaderne, og var ifølge Giovanni Pettinato Eblas alterego.

Khabur er den største sideelva til Eufrat i Syria. Sidan 1930-åra er det gjort mange arkeologiske utgravingar og undersøkingar i Kahburdalen og dei indikerer at det har budd folk her sidan eldre steinalder. Viktige stader som er utgrave er mellom andre Tell Halaf, Tell Brak, Tell Leilan, Tell Mashnaqa, Tell Mozan og Tell Barri.

Hamoukar, i Jazira regionen i nordøst Syria, huser restene av en av verdens eldste byer, noe som har fått forskere til å anta at byer I denne delen av verden oppsto mye tidligere enn man antok og at det var dette som med rette kan kalles for sivilisasjonens vugge.

Det tidligste navnet på Armenia er fra det sjette århundret f.vt. I sin trilingvistiske Behistun innskrift refererer Darius I den store av Persia til Urashtu på babylonsk som Armina på gammel persisk og Harminuya på elamittisk, men armenologer hevder det gamle persiske Armina og det greske Armenoi er fortsettelser av det assyriske toponymet Armânum, eller Armanî.

Farao Thutmose III av Egypt nevner folket ermenen i sitt 33 år av sin tid (1446 f.vt.), og sier at paradis hviler på sine fire pilarer i deres land. Swastikaen er et viktig symbol i hele Eurasia og trer også frem i Samarra i provinsen Salh ad Din i Irak, ved elven Tigris, 120 km fra hovedstaden Bagdad, omkring 6000 f.vt. Samarra er utgangspunktet for sumererne.

Ur, også kjent som Edessa, er det historiske navnet på en syrisk by i det nordlige Mesopotamia som ble grunnlagt på nytt på et antikt sted av Selevkos I Nikator. Dagens by er Şanlıurfa, som på grunn av likheten i navnet forbindes med Ur som Abraham dro ut fra.

Folket i Urartu kalte seg selv for Khaldini etter deres hovedgud Kaldi, også kjent som Haldi eller Haik, som var urartiernes krigergud, guden som kongene i Urartu ba til når de skulle til krig. I tillegg til de to andre gudene, stormguden Theispas av Kumenu og solguden Shivini av Tushpa, var han en av urartiernes tre hovedguder. Khaldis tempel befant seg i Ardini, også kjent som Muṣaṣir (Mu-ṣa-ṣir), som betyr slangens utgangspunkt.

Den indo-ariske guddinnen Kali dyrkes ofte i egen kraft, men like gjerne som kona til Shiva, eller Shivas feminine aspekt, mens Shivini, eller Artinis, som betyr soloppgang eller å våkne, var den urartiske solguden.

Maryannu er et gammelt ord for en krigeradel som dominerte mange samfunn i Sørvest Asia under bronsealderen, og betyr ung kriger. Armenia var den første kristne stat.

Hubal var en gud som ble dyrket i det før-islamske Arabia, især ved Kaba i Mekka. Arabere er også hurriere. Hurrierne utviklet seg til å bli kaukasere, semitter (heb-ariere) og indoeuropeere. Disse stammer fra Noah, eller nakh, folket. Vainakh folket levde i området rundt Ararat.

Mitra og Jesus er en og den samme. Naturen opprinnelige tilstand, eller harmoni, kommer fra me, fra mesh (staten Mitanni, guden Mitra, kongen Mita), som betyr lys, eller belyst, og den egyptiske gudinnen Maat, som på kinesisk er wu, inkludert wusun. Alt betegner lys, eller det belyst, som vil si frihet fra undertrykkelse og rettferdighet. Derfor den frygisk-armenske frigjøringslua.

Jeru-salem (arisk fred), eller Ari-samlem, og Jere-van, Ari-stamme), eller Arivan, er det samme som Jesus, Ar-sus er det samme som ar, eller den egyptiske guden ra. Reah, grekernes modergudinne, har bakgrunn fra Ararat (Urartu).

Enki (An-ki), som betyr jordas herre, og som var grunnlegger av vår sivilisasjon gjennom avataren Adapa, eller Adam, ble til EA, som ble til Jahve (Ja-we) og Allah (EA-la).

History of civilizations of Central Asia, v. 1: The Dawn of Civilization

Who Were the Hurrians? – Archaeology Magazine Archive

Filed under: Uncategorized

SKRIK!!!!!!

SKRIK!!!!!!

- Syrias barn skriker

Kanskje de destruktive kreftene i dag oppererer fra USA,

men de er inne i oss alle – og de er en del av oss

- vi må bare beherske dem!

Vredens dag kommer nærmere!

Vi meve ut fra nestekjærlighetsprinsippet!

- for hat vil møte mørke og nestekjærlighet vil møte lys!

Du må ikke sove

Du må ikke sitte trygt i ditt hjem

og si: Det er sørgelig, stakkars dem!

Du må ikke tåle så inderlig vel

den urett som ikke rammer dig selv!

Jeg roper med siste pust av min stemme:

Du har ikke lov til å gå der og glemme!

Filed under: Uncategorized

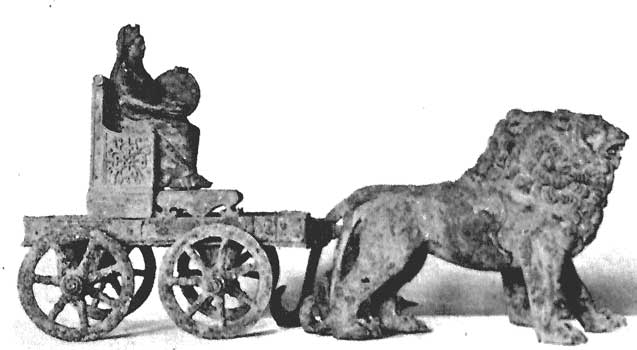

Gemini – The Divine Twins

Deeply integrated within Indo-European (IE) mythology is the importance given to the horse and chariot. In many IE mythologies, including Norse, Baltic, Celtic, Greek, Roman and Vedic, the sun and sometimes the moon are depicted as riders of a celestial chariot across the sky.

Within Indo-European mythology, the divine twins, associated with the constellation Gemini, are often related to horses and solar chariots. Examples include the horse-like Greek Dioscuri who pull the chariot of the sun across the sky, the Baltic Asviniai who represent twin solar horse gods and the similar Vedic Asvins.