![Sandro Botticelli + NASA (etc) via dimitri]()

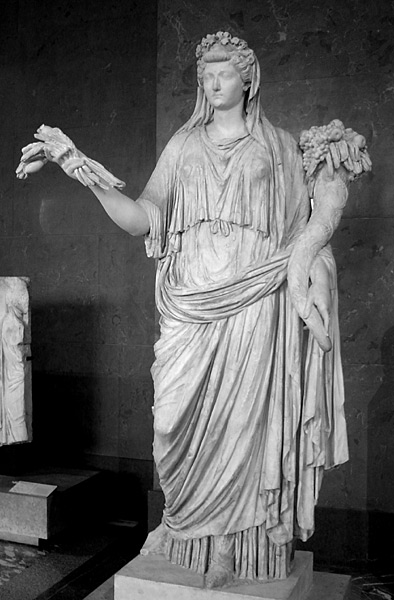

Mother goddess

Great Mother of the Gods

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![http://hybridchildrencommunity.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/a9.jpg]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![astrology_chartwheel 2]()

![]()

![]()

Great Mother of the Gods, in ancient Middle Eastern religion (and later in Greece, Rome, and Southwest Asia), mother goddess, the great symbol of the earth’s fertility.

As the creative force in nature she was worshiped under many names, including Ishtar (Babylon), Isis (Egypt), Astarte (Syria), Cybele (Phrygia), Demeter (Greece) and Ceres (Rome).

The later forms of her cult involved the worship of a male deity (her son or lover, e.g., Adonis, Osiris), whose death and resurrection symbolized the regenerative power of the earth. Syrian Adonis is Gauas or Aos, akin to Egyptian Osiris, the Semitic Tammuz and Baal Hadad, the Etruscan Atunis and the Phrygian Attis, all of whom are deities of rebirth and vegetation.

Dying-and-rising god

In comparative mythology, the related motifs of a dying god and of a dying-and-rising god (also known as a death-rebirth-deity) have appeared in diverse cultures. The concept of resurrection is found in the writings of some ancient non-Abrahamic religions in the Middle East. A few extant Egyptian and Canaanite writings allude to dying and rising gods such as Osiris and Baal.

In the more commonly accepted motif of a dying god, the deity goes away and does not return. The less than widely accepted motif of a dying-and-rising god refers to a deity which returns, is resurrected or is reborn, in either a literal or symbolic sense.

Beginning in the 19th century, a number of gods who would fit these motifs were proposed. Male examples include the ancient Near Eastern, Greek, and Norse deities Baal, Melqart, Adonis, Eshmun, Tammuz, Ra the Sun god with its fusion with Osiris/Orion, Jesus, and Dionysus. Female examples include Inanna/Ishtar, Persephone, and Bari.

The methods of death can be diverse, the Norse Baldr mistakenly dies by the arrow of his blind brother, the Aztec Quetzalcoatl sets himself on fire after over-drinking, and the Japanese Izanami dies of a fever. Some gods who die are also seen as either returning or bringing about life in some other form, in many cases associated with a vegetation deity related to a staple.

The very existence of the category “dying-and-rising-god” was debated throughout the 20th century, and the soundness of the category was widely questioned, given that many of the proposed gods did not return in a permanent sense as the same deity.

By the end of the 20th century, scholarly consensus had formed against the reasoning used to suggest the category, and it was generally considered inappropriate from a historical perspective.

Adonis

Adonis, in Greek mythology, is the god of beauty and desire, and is a central figure in various mystery religions. His religion belonged to women: the dying of Adonis was fully developed in the circle of young girls around the poet Sappho from the island of Lesbos, about 600 BC, as revealed in a fragment of Sappho’s surviving poetry.

Adonis has had multiple roles, and there has been much scholarship over the centuries concerning his meaning and purpose in Greek religious beliefs. He is an annually-renewed, ever-youthful vegetation god, a life-death-rebirth deity whose nature is tied to the calendar.

The Greek Adōnis was a borrowing from the Semitic word adon, meaning “lord”, which is related to Adonai, one of the names used to refer to the god of the Hebrew Bible and still used in Judaism to the present day. His name is often applied in modern times to handsome youths, of whom he is the archetype. Adonis is often referred to as the mortal god of Beauty.

Adonis, in Greek mythology, beautiful youth loved by Aphrodite and Persephone. When he was killed by a boar, both goddesses claimed him. Zeus decreed that he spend half the year above the ground with Aphrodite, the other half in the underworld with Persephone. His death and resurrection, symbolic of the seasonal cycle, were celebrated at the festival Adonia.

Attis

![]()

Attis was the consort of Cybele in Phrygian and Greek mythology. His priests were eunuchs, the Galli, as explained by origin myths pertaining to Attis and castration. Attis was also a Phrygian god of vegetation, and in his self-mutilation, death, and resurrection he represents the fruits of the earth, which die in winter only to rise again in the spring.

Aramazd

![]()

Aramazd (Zeus) – The father of all gods and goddesses, the creator of heaven and earth. The first two letters in his name, “AR” is the Indo-European root for sun, light, and life. Aramazd was the source of earth’s fertility, making it fruitful and bountiful. The celebration in his honor was called Am’nor, or New Year, which was celebrated on March 21 in the old Armenian calendar (also the Spring equinox).

Ara the Beautiful

Ara represents the heavenly Altar created by the gods of Mount Olympus to celebrate the defeat of the titans where the gods swore their allegiance to the supreme god Zeus (Jupiter). The smoke from the altar was said to pour out to create the Milky Way.

According to another account Ara was the altar on which the Centaur (Centaurus) offered his sacrifice of Lupus. Centaurus is traditionally depicted as carrying Lupus, the Wolf, to sacrifice on Ara, the altar. Ara was also known as the altar that Noah built after the great flood when his ark rested on Mt. Ararat.

Ara the Beautiful (also Ara the Handsome or Ara the Fair, Ara Geghetsik in Armenian), the god of spring, flora, agriculture, sowing and water, associated with Isis, Vishnu and Dionysus, as the symbol of new life, is a legendary Armenian hero notable in Armenian literature for the popular legend in which he was so handsome that the Assyrian queen Semiramis waged war against Armenia just to get him.

The battle began when Semiramis arrived in the region called Ararat. She ordered her commanders to capture Ara alive, but he was vanquished and killed by one of her sons. His body was found on the battlefield among the other slain soldiers.

BaHiyya means “beautiful” in Arabic.

![Ara]()

Ara – the Altar

Ara the Beautiful

The Armenian Gods

Ara, the sun-god

Osiris

![]()

Osiris (the Egyptian language name is variously transliterated Asar, Asari, Aser, Ausar, Ausir, Wesir, Usir, Usire or Ausare) is an Egyptian god, usually identified as the god of the afterlife, the underworld and the dead.

Osiris was classically depicted as a green-skinned man with a pharaoh’s beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive crown with two large ostrich feathers at either side, and holding a symbolic crook and flail.

Osiris was at times considered the oldest son of the Earth god Geb, and the sky goddess Nut, as well as being brother and husband of Isis, with Horus being considered his posthumously begotten son.

He was also associated with the epithet Khenti-Amentiu, which means “Foremost of the Westerners” — a reference to his kingship in the land of the dead. As ruler of the dead, Osiris was also sometimes called “king of the living”, since the Ancient Egyptians considered the blessed dead “the living ones”.

Osiris is first attested in the middle of the Fifth dynasty of Egypt, although it is likely that he was worshipped much earlier; the term Khenti-Amentiu dates to at least the first dynasty, also as a pharaonic title.

Osiris was considered not only a merciful judge of the dead in the afterlife, but also the underworld agency that granted all life, including sprouting vegetation and the fertile flooding of the Nile River. He was described as the “Lord of love”, “He Who is Permanently Benign and Youthful” and the “Lord of Silence”.

The Kings of Egypt were associated with Osiris in death — as Osiris rose from the dead they would, in union with him, inherit eternal life through a process of imitative magic. By the New Kingdom all people, not just pharaohs, were believed to be associated with Osiris at death, if they incurred the costs of the assimilation rituals.

Through the hope of new life after death, Osiris began to be associated with the cycles observed in nature, in particular vegetation and the annual flooding of the Nile, through his links with Orion and Sirius at the start of the new year.

Osiris was widely worshipped as Lord of the Dead until the suppression of the Egyptian religion during the Christian era.

Tammuz

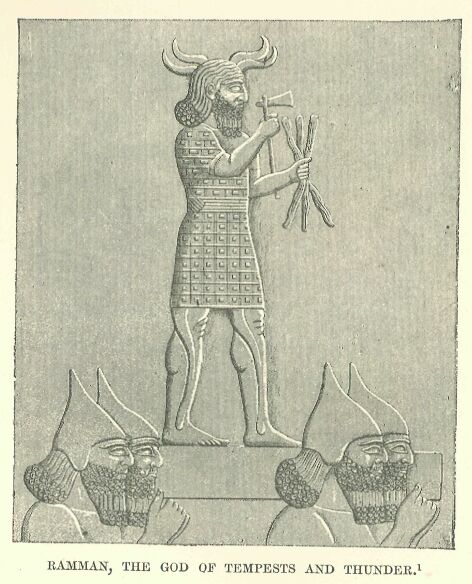

Tammuz (Akkadian: Duʾzu, Dūzu; Sumerian: Dumuzid (DUMU.ZI(D), “faithful or true son”) was the name of a Sumerian god of food and vegetation, also worshiped in the later Mesopotamian states of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia.

In Babylonia, the month Tammuz was established in honor of the eponymous god Tammuz, who originated as a Sumerian shepherd-god, Dumuzid or Dumuzi, the consort of Inanna and, in his Akkadian form, the parallel consort of Ishtar.

The Aramaic name “Tammuz” seems to have been derived from the Akkadian form Tammuzi, based on early Sumerian Damu-zid. The later standard Sumerian form, Dumu-zid, in turn became Dumuzi in Akkadian. Tamuzi also is Dumuzid or Dumuzi.

Beginning with the summer solstice came a time of mourning in the Ancient Near East, as in the Aegean: the Babylonians marked the decline in daylight hours and the onset of killing summer heat and drought with a six-day “funeral” for the god.

Recent discoveries reconfirm him as an annual life-death-rebirth deity: tablets discovered in 1963 show that Dumuzi was in fact consigned to the Underworld himself, in order to secure Inanna’s release, though the recovered final line reveals that he is to revive for six months of each year.

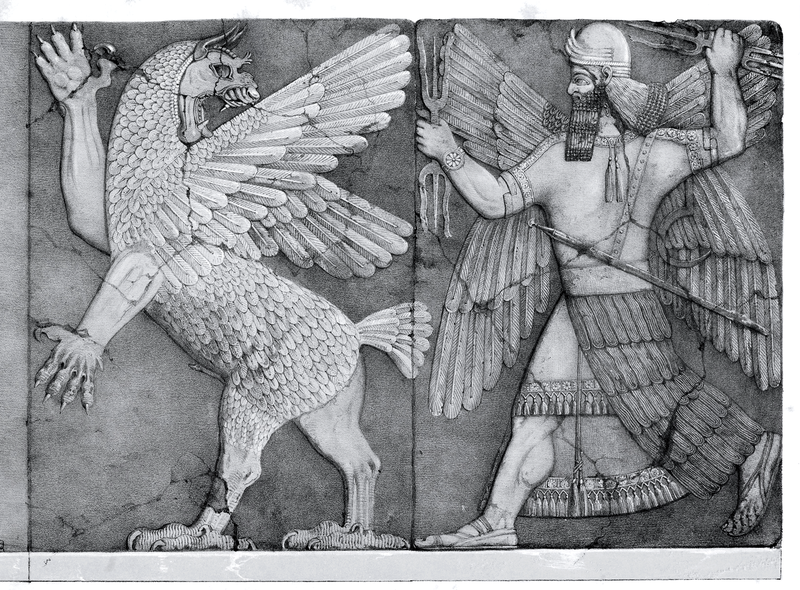

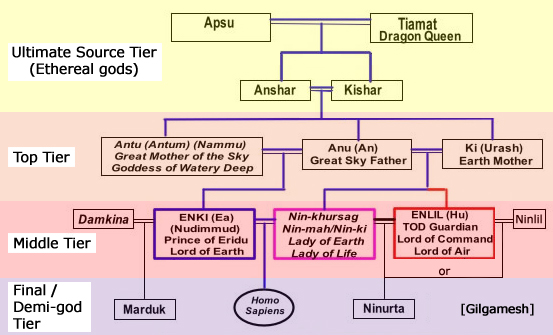

Enki

![]()

Enki and Gilgamesh

Enki (EN.KI(G)) is a god in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water.”

In Sumerian E-A means “the house of water”, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at the city of Eridu, where he was the patron god. His influence of his cult later spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

The main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu.

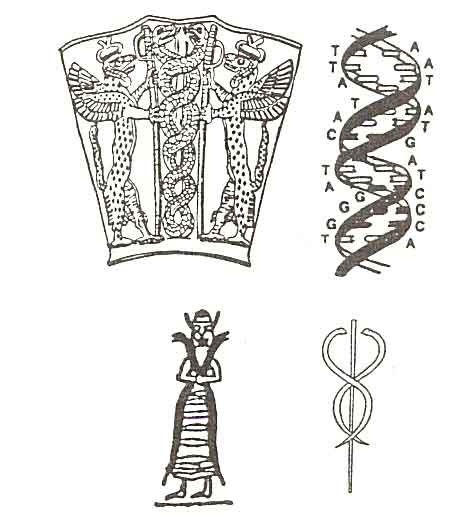

He was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, very similar to the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water’. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

The cosmogenic myth common in Sumer was that of the hieros gamos, a sacred marriage where divine principles in the form of dualistic opposites came together as male and female to give birth to the cosmos.

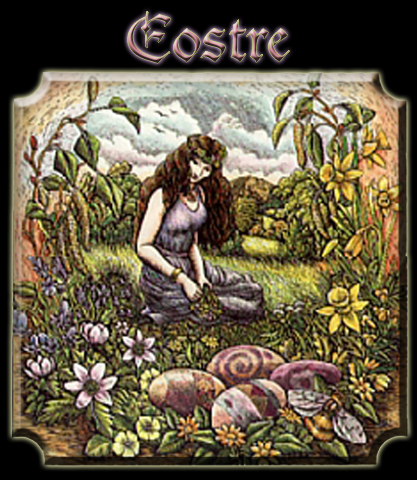

The Mother goddess

Mother goddess is a term used to refer to a goddess who represents and/or is a personification of nature, motherhood, fertility, creation, destruction or who embodies the bounty of the Earth. When equated with the Earth or the natural world, such goddesses are sometimes referred to as Mother Earth or as the Earth Mother.

The Earth Mother is a motif that appears in many mythologies. The Earth Mother is a fertile goddess embodying the fertile earth and typically, the mother of other deities, and so, also are seen as patronesses of motherhood. This is generally thought of as being because the earth was seen as being the mother from whom all life sprang.

The idea that the fertile earth is female and nurtures humans, was not limited to the Greco-Roman world. These traditions were greatly influenced by earlier cultures in the ancient Middle East.

Figurines of fertility goddesses, both individually sculpted and mass-produced, have been found at nearly all Near Eastern sites. The earliest such figurines date back to the Neolithic era (7th and 6th millennia BCE) and they continue to be made throughout Near Eastern history. Very little is known about the goddess or her cult as so little concerning them was written down in ancient times.

Many different goddesses have represented motherhood in one way or another, and some have been associated with the birth of humanity as a whole, along with the universe and everything in it. Others have represented the fertility of the earth.

Several small, voluptuous figures have been found during archaeological excavations of the Upper Paleolithic, the Venus of Willendorf, perhaps, being the most famous. This sculpture is estimated to have been carved 24,000–22,000 BCE. Some archaeologists believe they were intended to represent goddesses, while others believe that they could have served some other purpose.

These figurines predate, by many thousands of years, the available records of the goddesses listed below as examples of mother goddesses, so although they seem to conform to the same generic type, it is not clear whether they, indeed, were representations of a goddess or whether, if they are, there was any continuity of religion that connects them with Middle Eastern and Classical deities.

The Paleolithic period extends from 2.5 million years ago to the introduction of agriculture around 10,000 BCE. Archaeological evidence indicates that humans migrated to the Western Hemisphere before the end of the Paleolithic; so cultures around the world share its characteristics. It is the prehistoric era distinguished by the development of stone tools, and covers the greatest portion of humanity’s time on Earth.

While most Paleolithic figurines are from the Upper Paleolithic period, the Venus of Berekhat Ram found at Berekhat Ram on the Golan Heights is a Middle Paleolithic artefact of the later Acheulian period and possibly was made by individuals identified as, Homo erectus.

Diverse images of what are believed to be Mother Goddesses have been discovered that also date from the Neolithic period, the New Stone Age, which ranges from approximately 10,000 BCE, when the use of wild cereals led to the beginning of farming and, eventually, to agriculture.

The end of this Neolithic period is characterized by the introduction of metal tools as the skill appeared to spread from one culture to another, or arise independently as a new phase in an existing tool culture, and eventually, became widespread among humans.

Regional differences in the development of this stage of tool development are quite varied. In other parts of the world, such as Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, independent domestication events led to their own patterns of development, while distinctive Neolithic cultures arose independently in Europe and Southwest Asia.

During this time, native cultures appear in the Western Hemisphere, arising out of older Paleolithic traditions that were carried during migration. Regular seasonal occupation or permanent settlements begin to be seen in excavations.

Herding and keeping of cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs is evidenced along with the presence of dogs. Almost without exception, images of what Marija Gimbutas interpreted as Mother Goddesses have been discovered in all of these cultures.

James Frazer (author of The Golden Bough) and others (such as Jane Ellen Harrison, Robert Graves and Marija Gimbutas) advance the idea that goddess worship in ancient Europe and the Aegean was descended from Pre-Indo-European neolithic matriarchies.

Gimbutas argued that the thousands of female images from Old Europe (archaeology) represented a number of different groups of goddess symbolism, notably a “bird and snake” group associated with water, an “earth mother” group associated with birth, and a “stiff nude” group associated with death, as well as other groups.

Gimbutas maintained that the “earth mother” group continues the paleolithic figural tradition discussed above, and that traces of these figural traditions may be found in goddesses of the historical period. According to Gimbutas’ Kurgan Hypothesis, Old European cultures were disrupted by expansion of Indo-European speakers from southern Siberia.

In 1968 the archaeologist Peter Ucko proposed that the many images found in graves and archaeological sites of Neolithic cultures were toys. The graves he was describing dated from Predynastic Egypt and Neolithic Crete, and mostly, contained adults, however.

Anatolian

![]()

Anatolian Mother Goddes, Çatal höyük, the Konya region, Turkey (6000 BC)

The Seated Woman of Çatal Hüyük (also Çatalhöyük) is a baked-clay, nude female form, seated between feline-headed arm-rests. It is generally thought to depict a corpulent and fertile Mother Goddess in the process of giving birth while seated on her throne, which has two hand rests in the form of feline (leopard or panther) heads.

The statuette, one of several iconographically similar ones found at the site, is associated to other corpulent Neolithic goddess figures, of which the most famous is the Venus of Willendorf. The similarity to later iconography of the Anatolian Mother Goddess Cybele in the first millennium BC is striking.

It is a neolithic sculpture shaped by an unknown artist. It was unearthed by archeologist James Mellaart in 1961. When it was found, its head and hand rest of the right side was missing. The current head and the hand rest are modern replacements. The sculpture is at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey.

![File:Cybele Getty Villa 57.AA.19.jpg]()

Cybele

Cybele was an originally Anatolian mother goddess; she has a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatal höyük where the statue of a pregnant goddess seated on a lion throne was found in a granary. She is Phrygia’s only known goddess, and was probably its state deity. Her Phrygian cult was adopted and adapted by Greek colonists of Asia Minor and spread from there to mainland Greece and its more distant western colonies from around the 6th century BC.

Numerous female figurines from Neolithic Çatalhöyük in Anatolia have been interpreted as evidence of a mother-goddess cult, c.7500 BC. James Mellaart, who led excavation at the site in the 1960s, suggests that the figures represent a Great goddess, who headed the pantheon of an essentially matriarchal culture.

A seated female figure, flanked by what Mellart describes as lionesses, was found in a grain-bin; she may have intended to protect the harvest and grain.

Reports of more recent excavations at Çatalhöyük conclude that overall, the site offers no unequivocal evidence of matriarchal culture or a dominant Great Goddess; the balance of male and female power appears to have been equal. The seated or enthroned goddess-like figure flanked by lionesses, has been suggested as a prototype Cybele, a leading deity and Mother Goddess of later Anatolian states.

Near Eastern

![File:FemaleStatuetteSamarra6000BCE.jpg]()

Mother Goddes, Samarra, Iraq (6000 BC)

Many modern scholars believe that many of the Sumerian goddesses known from later myths and hymns were originally local aspects of the indigenous mother goddess. Prominent among such goddesses were Ninhursaga, Ninmah, Damgalnunna, Ninmah, Nintu and Nammu.

In Sumerian mythology Ki is the earth goddess. In Akkadian orthography she has the syllabic values gi,ge,qi,qe (for toponyms). Some scholars identify her with Ninhursag (lady of the mountains), the earth and fertility Mother Goddess, who had the surnames Nintu (lady of birth), Mamma, and Aruru.

Many of these goddesses were married off to the gods in the Old Babylonian period, after which they became increasingly regarded as taking a mediating and intercessionary role.

Due to being mother of Gilgamesh, Ninsun is also regarded as a Mother Goddess in general Mesopotamian mythology. She is Asherah in Canaan and `Ashtart in Syria. The Sumerians wrote erotic poetry about their mother goddess Ninhursag.

The title “The mother of life” later was given to the Akkadian Goddess Kubau, and hence to Hurrian Hepa, emerging in Hebrew as Eve (Heva) and Phygian Kubala (Cybele).

Old European

![Fil:SoborulZeitelor3Cucuteni.JPG]()

From 5500 to 2750 BC the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture flourished in the region of modern-day Romania, Moldova, and southwestern Ukraine, leaving behind ruins of settlements of as many as 15,000 residents who practiced agriculture and domesticated livestock. They also left behind many ceramic remains of pottery and clay figurines. Some of these figurines appear to represent the mother goddess (see images in this article).

Egyptian

![]()

Mother goddesses are present in the earliest images discovered among the archaeological finds in Ancient Egypt. An association is drawn to the early goddesses of Egypt with animals seen as good mothers – the lioness, cow, hippopotamus, white vulture, cobra, scorpion, and cat – as well as, to the life-giving primordial waters, the sun, the night sky, and the earth herself.

Even through the transition to a paired pantheon of male deities matched or “married” to each goddess and during the male-deity-dominated pantheon that arose much later, the mother goddesses persisted into historical times (such as Hathor and Isis). Advice from the oracles associated with these goddesses guided the rulers of Egypt.

The Two Ladies, Wadjet and Nekhbet, remained patron deities of the rulers of Ancient Egypt throughout every dynasty, including that of Akhenaten (who often is described as having abandoned all but one solar deity), and they all bore their images on their crowns and included special names associated with these goddesses among their titles.

The image of Isis nursing her son was worshiped into the sixth century A.D. and has been resurrected by contemporary “cults” of an Earth Mother. That imagery may have been adopted by early Christians as well.

Only in late Egyptian Mythology does the reverse seem true – Geb is the Earth Father while Nut is the Sky Mother, but the primordial and great goddess of Egypt was Mut, the source of all life and the mother of all. The mound of earth from which life sprang was Mut.

An Egyptian earth and fertility deity, Geb, was male and he was considered father of all snakes, however, the mound from which all life was created by parthenogenesis, represents Mut, the primal “mother of all who was not born of any”. She is the more appropriate figure to discuss as the mother goddess in Ancient Egyptian religion.

The number of Egyptian goddesses who are depicted as important mother deities is numerous because of regional cults of many very early cultures and a major unification of two ancient countries into one, whose written history only begins at approximately 3150 BC.

It is estimated that the some early cultures that eventually became parts of Ancient Egypt date back to 8000 BC. and that human occupation of the Nile Valley by modern hunter gatherer societies dates back 120 thousand years.

Indo-Aryan

In Hinduism, Durga represents the empowering and protective nature of motherhood. From her forehead sprang Kali, who defeated Durga’s enemy, Mahishasura. Kali (the feminine form of Kaal” i.e. “time”) is the primordial energy as power of Time, literally, the “creator or doer of time”—her first manifestation. after time, she manifests as “space”, as Tara, from which point further creation of the material universe progresses.

The divine Mother, Devi Adi parashakti, manifests herself in various forms, representing the universal creative force. She becomes Mother Nature (Mula Prakriti), who gives birth to all life forms as plants, animals, and such from Herself, and she sustains and nourishes them through her body, that is the earth with its animal life, vegetation, and minerals.

Ultimately she re-absorbs all life forms back into herself, or “devours” them to sustain herself as the power of death feeding on life to produce new life. She also gives rise to Maya (the illusory world) and to prakriti, the force that galvanizes the divine ground of existence into self-projection as the cosmos. The Earth itself is manifested by Adi parashakti. Hindu worship of the divine Mother can be traced back to pre-vedic, prehistoric India.

The form of Hinduism known as Shaktism is strongly associated with Samkhya, and Tantra Hind philosophies and ultimately, is monist. The primordial feminine creative-preservative-destructive energy, Shakti, is considered to be the motive force behind all action and existence in the phenomenal cosmos.

The cosmos itself is purusha, the unchanging, infinite, immanent, and transcendent reality that is the Divine Ground of all being, the “world soul”. This masculine potential is actualized by feminine dynamism, embodied in multitudinous goddesses who are ultimately all manifestations of the One Great Mother.

Mother Maya or Shakti, herself, can free the individual from demons of ego, ignorance, and desire that bind the soul in maya (illusion). Practitioners of the Tantric tradition focus on Shakti to free themselves from the cycle of karma.

In Hinduism, the Mother of all creation is called “Gayatri”. Gayatri is the name of one of the most important Vedic hymns consisting of twenty-four syllables. One of the sacred texts says, “The Gayatri is Brahma, Gayatri is Vishnu, Gayatri is Shiva, the Gayatri is Vedas” and Gayatri later came to be personified as a goddess.

She is shown as having five heads and is usually seated within a lotus. The four heads of Gayatri represent the four Vedas and the fifth one represents the almighty deity. In her ten hands, she holds all the symbols of Lord Vishnu. She is another consort of Lord Brahma.

In Hinduism and Buddhism the specific local indwelling mother deity of Earth (as opposed to the mother deity of all creation) is called Bhūmi. Gautama Buddha called upon Bhumi as his witness when he achieved Enlightenment.

Aegean

![File:Rhea MKL1888.png]()

![Rhea Cybele, mother of the gods, riding a lion | Greek vase, Athenian red figure kylix]()

![]()

![File:Livia statue.jpg]()

Mother goddess, Rhea/Opis, Greek mythology

![File:Iuno Petit Palais ADUT00168.jpg]()

Mother goddess, Juno, Rome

In the Aegean, Anatolian, and ancient Near Eastern culture zones, Cybele, the primordial deity Gaia, and Rhea were worshiped as Mother goddesses. In Mycenae the great goddess often was represented by a column.

Olympian goddesses of classical Greece with mother goddess attributes include Hera and Demeter. “The goddesses of Greek polytheism, so different and complementary, are nonetheless, consistently similar at an earlier stage, with one or the other simply becoming dominant in a sanctuary or city. Each is the Great Goddess presiding over a male society; each is depicted in her attire as Mistress of the Beasts, and Mistress of the Sacrifice, even Hera and Demeter”.

The Minoan goddess represented in seals and other remains many of whose attributes were absorbed into Artemis, seems to have been a mother goddess type, for in some representations she suckles the animals that she holds.

The archaic local goddess worshiped at Ephesus, whose cult statue was adorned with necklaces and stomachers hung with rounded protuberances who was later also identified by Hellenes with Artemis, was probably also a mother goddess.

In ancient Roman religion, Tellus or Terra Mater (“Mother Earth”) was a goddess of the earth and agriculture. Her festivals and rituals often connected her to Ceres, goddess of grain, agriculture, fertility, and mothering.

Venus was regarded as a mother of the Roman people through her half-mortal son Aeneas, who led refugees from the Trojan War to settle in Italy. The family of Julius Caesar claimed to have descended from Venus.

In this capacity she was given cult as Venus Genetrix (Venus the Begetter). In the later Imperial era, she was included among the many manifestations of a syncretised Magna Dea (Great Goddess), who could be manifested as any goddess at the head of a pantheon, such as Juno or Minerva.

Celtic

The Irish goddess Anu, sometimes known as Danu, has an aspect as a mother goddess, judging from the Dá Chích Anann near Killarney, County Kerry. Irish literature names the last and most favored generation of deities as “the people of Danu” (Tuatha De Danann).

The Welsh have a similar figure called Dôn who is often equated with Danu and identified as a mother goddess. Sources for this character date from the Christian period, however, so she is referred to simply as a “mother of heroes” in the Mabinogion. The character’s (assumed) origins as a goddess are obscured.

The Celts of Gaul worshipped a goddess known as Dea Matrona (“divine mother goddess”) who was associated with the Marne River. Similar figures known as the Matres (Latin for “mothers”) are found on altars in Celtic as well as Germanic areas of Europe.

The Irish Celts worshipped Danu, whilst the Welsh Celts worshipped Dôn. Hints of their names occur throughout Europe, such as the Don river, the Danube River, the Dnestr, and the Dnepr, suggest that they stemmed from an ancient Proto-Indo-European goddess.

Nordic

![]()

In Norse mythology the earth is personified as Jörð, Hlöðyn, and Fjörgyn and Fjörgynn. In Germanic paganism, the Earth Goddess is referred to as Nertha.

In the first century BC, Tacitus recorded rites amongst the Germanic tribes focused on the goddess Nerthus, whom he calls Terra Mater, ‘Mother Earth’. Prominent in these rites was the procession of the goddess in a wheeled vehicle through the countryside. Among the seven or eight tribes said to worship her, Tacitus lists the Anglii and the Longobardi.

Among the later Anglo-Saxons, a Christianized charm known as Æcerbot survives from records from the tenth century. The charm involves a procession through the fields while calling upon the Christian God for a good harvest, that invokes ‘eorþan modor’ (Earth Mother) and ‘folde, fira modor,’ (Earth, mother of men).

In skaldic poetry, the kenning, “Odin’s wife”, is a common designation for the Earth. Bynames of the Earth in Icelandic poetry include Jörð, Fjörgyn, Hlóðyn, and Hlín. Hlín is used as a byname of both Jörð and Frigg.

Fjörgynn (a masculine form of Fjörgyn) is said to be Frigg’s father, while the name Hlóðyn is most commonly linked to Frau Holle, as well as to a goddess, Hludana, whose name is found etched in several votive inscriptions from the Roman era.

Connections have been proposed between the figure of Nerthus and various figures (particularly figures counted amongst the Vanir) recorded in thirteenth century Icelandic records of Norse mythology, including Frigg.

Due to potential etymological connections, the Norse god Njörðr has been proposed as the consort of Nerthus. In the Poetic Edda poem, Lokasenna, Njörðr is said to have fathered his famous children by his own sister. This sister remains unnamed in surviving records.

Due to specific terms used to describe the figure of Grendel’s mother from the poem Beowulf, some scholars have proposed that the figure of Grendel’s mother, like the poem itself, may have derived from earlier traditions originating from Germanic paganism.

Slavic

Mat Zemlya and her handmaiden Mokosh are two major deities in Slavic mythology. They date back to the Primary Chronicle and working together, they can give life and take it away. Mat Zemlya is Mother Earth, and Mokosh is the moisture that makes it fertile.

In Lithuanian mythology Gaia – Žemė (Lithuanian for “Earth”) is daughter of Sun and Moon. Also she is wife of Dangus (Lithuanian for “Sky”) (Varuna).

Chinese

![File:QueenMotherOfTheWest-Earthenware-EasternHanDynasty-ROM-May8-08.png]()

Mother Goddes – China

Queen Mother of the West, Xi wang mu, earthenware

second century, Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD)

Xi Wangmu (Hsi Wang-mu; literally “Queen Mother of the West”) is a Chinese goddess known from the ancient times. The growing popularity of the Queen Mother of the West, as well as the beliefs that she was the dispenser of prosperity, longevity, and eternal bliss took place during the second century BC when the northern and western parts of China were able to be better known because of the opening of the Silk Routes.

From her name alone some of her most important characteristics are revealed: she is royal, female, and is associated with the west. Originally, from the earliest known depictions of her in the “Guideways of Mountains and Seas” during the Zhou Dynasty, she was a ferocious goddess with the teeth of a tiger, who sent Pestilence down upon the world. After she was adopted into the Taoist pantheon, she was transformed into the goddess of life and immortality.

The Queen Mother of the West usually is depicted holding court within her palace on the mythological Mount Kunlun, usually supposed to be in western China (a modern Mount Kunlun is named after this). Her palace is believed to be a perfect and complete paradise, where it was used as a meeting place for the deities and a cosmic pillar where communications between deities and humans were possible.

The Kunlun mountains are believed to be a paradise of Taoism. The first to visit this paradise was, according to the legends, King Mu (976-922 BCE) of the Zhou Dynasty. He supposedly discovered there the Jade Palace of Huang-Di, the mythical Yellow Emperor and originator of Chinese culture, and met Hsi Wang Mu (Xi Wang Mu), the ‘Spirit Mother of the West’ usually called the ‘Queen Mother of the West’, who was the object of an ancient religious cult which reached its peak in the Han Dynasty, also had her mythical abode in these mountains.

One Chinese myth tells a story about Mu, who dreamed of being an immortal god. He was determined to visit the heavenly paradise and taste the peaches of immortality. A brave charioteer named Zaofu used his chariot to carry the king to his destination. The Mu Tianzi Zhuan, a fourth-century BC romance, describes Mu’s visit to Xi Wangmu.

Probably one of the best known stories of contact between a goddess and a mortal ruler is between King Mu of the Zhou Dynasty and the Queen Mother of the West. There are several different accounts of this story but they all agree that King Mu, one of the greatest rulers of the Zhou, set out on a trip with his eight chargers to the far western regions of his empire. As he obtains the eight chargers and has the circuit of his realm, it proves that he has the Mandate of Heaven.

On his journey he encounters the Queen Mother of the West on the mythical Mount Kunlun. They then have a love affair, and King Mu hoping to obtain immortality, gives the Queen Mother important national treasures. In the end he must return to the human realm, and does not receive immortality.

The relationship between the Queen Mother of the West and King Mu has been compared to that of Taoist master and disciple.(Bernard, 2000: 206) She passes on secret teaching to him at his request and he, the disciple, fails to benefit, and dies like any other mortal.

The Bamboo Annals record that in the 9th year of reign of the legendary Chinese ruler Shun, “messengers from the western Wang-mu (Queen Mother) came to do him homage.”

Shun, also known as Emperor Shun and Chonghua, was a legendary leader of ancient China, and one of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors.

Shun’s ancestral name is Yao, his clan name is Youyu. His given name was Chonghua. Shun is sometimes referred to as the Great Shun or as Yu Shun. The “Yu” in “Yu Shun” was the name of the fiefdom, which Shun received from Yao; thus, providing him the title of “Shun of Yu”).

According to traditional sources, Shun received the mantle of leadership from Emperor Yao at the age of 53, and then died at the age of 100 years. Before his death Shun is recorded as relinquishing his seat of power to Yu: an event which is supposed to have eventuated in the establishment of the Xia Dynasty. Shun’s capital was located in Puban, presently located in Shanxi).

Yu the Great (c. 2200 – 2100 BC), was a legendary ruler in ancient China famed for his introduction of flood control, inaugurating dynastic rule in China by founding the Xia Dynasty, and for his upright moral character. Yu and other “sage-kings” of Ancient China were lauded by Confucius and other Chinese teachers, who praised their virtues and morals

The Xunzi, a third-century BCE classic of statecraft written by a follower of Confucius, wrote that “Yu studied with the Queen Mother of the West”. This passage refers to Yu the Great, the legendary founder of the Xia dynasty, and posits that the Queen Mother of the West was Yu’s teacher. It is believed that she grants Yu both legitimacy, and the right to rule, and the techniques necessary for ruling.

The fact that she taught Yu gives her enormous power, since the belief in Chinese thinking is that the teacher automatically surpasses the pupil in seniority and wisdom.

Turkic

Yer Tanrı is the mother of Umai, also known as Ymai or Mai, the mother goddess of the Turkic Siberians. She is depicted as having sixty golden tresses, that resemble the rays of the sun. She is thought to have once been identical with Ot of the Mongols.

Christian

The Normans had a major influence on English Romanesque architecture when they built a large numbers of Christian monasteries, abbeys, churches, and cathedrals. These Romanesque styles originated in Normandy and became widespread in north western Europe, particularly in England, which has the largest number of surviving examples.

Sheela na Gig is a common stone carving found in Romanesque Christian churches scattered throughout Europe. These female figures are found in Ireland, Great Britain, France, Spain, Switzerland, Norway, Belgium, and in the Czech Republic.

Their meaning is not clearly identifiable as Christian, and may be a concept that survived from ancient forms of yoni worship and sacred prostitution practiced in the goddess temples. Some of the figures seem to be elements of earlier structures, perhaps devoted to goddess worship.

Other common motifs on Christian churches of the same time period are spirals and ouroboros or dragons swallowing their tails, which is a reference to rebirth and regeneration, a concept well known in pantheism.

Other creatures including the succubus make an appearance in the sculptural reliefs of the church that have a long history in the oral tradition of previous civilizations that preceded Christianity that may relate to earlier goddess worship.

Most Christians regard the Mary, the mother of Jesus, as the Theotokos (or Mother of God). For many believers as a “spiritual mother,” since she not only fulfills a maternal role, but is often viewed as a protective and intercessory force, a divinely established mediator for humanity, but stress that she is not worshipped as a divine “mother goddess”.

The Roman Catholic, Anglican, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Orthodox churches identify “the woman clothed in sun” described in Revelation 12 as Mary because in verse 5, this woman is said to have given “birth to a son, a male child, destined to rule all the nations with an iron rod”, whom they identify as Jesus Christ. Then, in verse 17 of Revelation 12, the Bible describes “the rest of her offspring” as “those who keep God’s commandments and bear witness to Jesus.”

These Christians believe themselves to be the other “offspring” because they try to “keep God’s commandments and bear witness to Jesus,” and thus, they embrace Mary as their “mother”.

They also cite John 19:26–27 where Jesus entrusts his mother to John the Apostle as evidence that Mary is the mother of all Christians, taking the command “behold thy mother” to apply generally. The Roman Catholics refer to her as, the Blessed Virgin Mary.

In 300 A.D., the Blessed Virgin Mary was worshipped as a Mother Goddess in the Christian sect Collyridianism, which was found throughout Saudi Arabia. Collyridianism was made up mostly of women followers and female priests.

Followers of Collyridianism were known to make bread and wheat offerings to the Virgin Mary, along with other sacrificial practices. The cult was heavily condemned as heretical and schismatic by the Roman Catholic Church and was preached against by Epiphanius of Salamis, who exposed the group in his recollective writings entitled, Panarion.

As motherhood is a recurring concept in many religions, the Blessed Virgin Mary received many titles in the Roman Catholic Church, such as Queen of Heaven and Our Lady, Star of the Sea, that are familiar from earlier Near Eastern traditions.

Due to this correlation, some Protestants often accuse Catholics of viewing Mary as a goddess, but the Roman Catholic Church and Orthodox churches always have condemned “worship as adoration” of Mary.

Part of this accusation is due to the Catholic practice of prayer as a means of communication rather than as a means of worship. Catholics believe that the faithful dead have achieved eternal life and can intercede for people here on earth.

Concepts of Mother Goddess worshipped is heavily condemned by the Holy See as it had been suppressed and condemned among the Collyridianist sect in 300 A.D.

Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

This paper discusses forms of a ‘Great Mother’ goddess as she evolved in prehistoric and early historic Anatolia, her movements throughout Asia Minor, her transmission to Greece and Rome, and her worship thence throughout the ancient world. It also addresses the controversy of how and whether the Phrygian and later Greco-Roman goddess Cybele is connected to the Anatolian Kubaba mentioned in Hittite texts and later worshipped in Carchemish.

Through my translations of Hittite, Phrygian, Greek and Roman texts I try to explicate the relationship of the Anatolian Kubaba and Phrygian, Greek, and Roman Cybele.

In pre-Neolithic and Neolithic Anatolia there were several cultures to which belong female figurines associated with felines. The earliest carved on rock in an area between pillars containing depictions of felines. The double mound of Çatal höyük, 45 kilometers south of modern Konya, dates from the eighth to the sixth millennia BC.

…

Although the Kybileian Mountain Mother may not be related linguistically to the earlier Kubaba, the iconography of female figure, feline, throne, and mural crown links Kubaba to the Hittite Great Goddess, the sun-goddess of Arinna, or Hebat, depicted as a Mistress of Animals and as mother of the gods; the feline links her to several pre historic cultures of Anatolia. Thus there is continuity of a “Great Mother” figure accompanied by lions from pre-Neolithic Anatolia through the first centuries of this era.

Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

Ancient Felines and the Great-Goddess in Anatolia: Kubaba and Cybele

Sumerian creation myth

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The primordial chaos

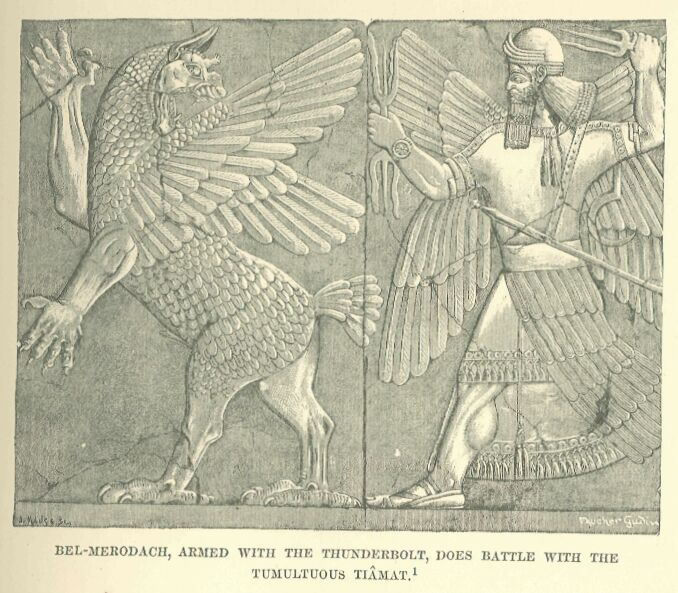

In Mesopotamian Religion (Sumerian, Assyrian, Akkadian and Babylonian), Tiamat is a chaos monster, a primordial goddess of the ocean, mating with Abzû (the god of fresh water) to produce younger gods.

Tiamat was later known as Thalattē (as a variant of thalassa, the Greek word for “sea”) in the Hellenistic Babylonian Berossus’ first volume of universal history.

It is thought that the name of Tiamat was dropped in secondary translations of the original religious texts (written in the East Semitic Akkadian language) because some Akkadian copyists of Enûma Elish substituted the ordinary word for “sea” for Tiamat, since the two names had become essentially the same due to association.

Tehom, literally the Deep or Abyss, refers to the Great Deep of the primordial waters of creation in the Bible. Tehom is a cognate of the Akkadian word tamtu and Ugaritic t-h-m which have similar meaning. As such it was equated with the earlier Sumerian Tiamat.

Tiamat was the “shining” personification of salt water who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Apsu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is “Ummu-Hubur who formed all things”.

The Babylonian epic Enuma Elish is named for its incipit: “When above” the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, “the first, the begetter”, and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, “she who bore them all”; they were “mixing their waters”.

Harriet Crawford finds this “mixing of the waters” to be a natural feature of the middle Persian Gulf, where fresh waters from the Arabian aquifer mix and mingle with the salt waters of the sea.

This characteristic is especially true of the region of Bahrain, whose name in Arabic means “two seas”, and which is thought to be the site of Dilmun, the original site of the Sumerian creation beliefs. The difference in density of salt and fresh water drives a perceptible separation.

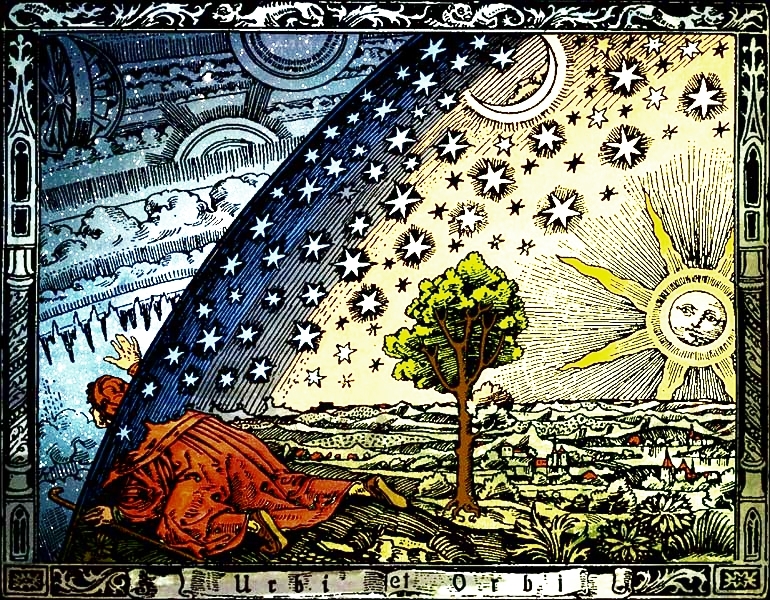

Chaos refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, more specifically the initial “gap” created by the original separation of heaven and earth.

Greek χάος means “emptiness, vast void, chasm, abyss”, from the verb χαίνω, “gape, be wide open, etc.”, from Proto-Indo-European ghen-, cognate to Old English geanian, “to gape”, whence English yawn.

Hesiod and the Pre-Socratics use the Greek term in the context of cosmogony. Hesiod’s chaos has often been interpreted as a moving, formless mass from which the cosmos and the gods originated, but Eric Voegelin sees it instead as creatio ex nihilo, much as in the Book of Genesis.

The term tohu wa-bohu of Genesis 1:2 has been shown to refer to a state of non-being prior to creation rather than to a state of matter. The Septuagint makes no use of χάος in the context of creation, instead using the term for גיא, “chasm, cleft”, in Micha 1:6 and Zacharia 14:4.

Nevertheless, the term chaos has been adopted in religious studies as referring to the primordial state before creation, strictly combining two separate notions of primordial waters or a primordial darkness from which a new order emerges and a primordial state as a merging of opposites, such as heaven and earth, which must be separated by a creator deity in an act of cosmogony.

In both cases, chaos referring to a notion of a primordial state contains the cosmos in potentia but needs to be formed by a demiurge before the world can begin its existence.

This model of a primordial state of matter has been opposed by the Church Fathers from the 2nd century, who posited a creation ex nihilo by an omnipotent God.

In modern biblical studies, the term chaos is commonly used in the context of the Torah and their cognate narratives in Ancient Near Eastern mythology more generally. Parallels between the Hebrew Genesis and the Babylonian Enuma Elish were established by H. Gunkel in 1910. Besides Genesis, other books of the Old Testament, especially a number of Psalms, some passages in Isaiah and Jeremiah and the Book of Job are relevant.

Gnostics used this text to propose that the original creator god, called the “Pléroma” or “Bythós” (from the Greek, meaning “Deep”) pre-existed Elohim, and gave rise to such later divinities and spirits by way of emanations, progressively more distant and removed from the original form.

Abzu

The Abzu, also called engur, literally, ab=’water’ (or ‘semen’) zu=’to know’ or ‘deep’, was the name for fresh water from underground aquifers that was given a religious fertilizing quality in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology. Lakes, springs, rivers, wells, and other sources of fresh water were thought to draw their water from the abzu.

Abzu (apsû) is depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Elish, taken from the library of Assurbanipal (c 630 BCE) but which is about 500 years older. In this story, he was a primal being made of fresh water and a lover to another primal deity, Tiamat, who was a creature of salt water.

The Enuma Elish begins: When above the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, the first, the begetter, and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, she who bore them all; they were still mixing their waters, and no pasture land had yet been formed, nor even a reed marsh…

In the city Eridu, Enki’s temple was known as E2-abzu (house of the cosmic waters) and was located at the edge of a swamp, an abzu. Certain tanks of holy water in Babylonian and Assyrian temple courtyards were also called abzu (apsû). Typical in religious washing, these tanks were similar to the washing pools of Islamic mosques, or the baptismal font in Christian churches.

The pool of the Abzu at the front of his temple was adopted also at the temple to Nanna (Akkadian Sin) the Moon, at Ur, and spread from there throughout the Middle East. It is believed to remain today as the sacred pool at Mosques, or as the holy water font in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.

The Sumerian god Enki (Ea in the Akkadian language) was believed to have lived in the abzu since before human beings were created. His wife Damgalnuna, his mother Nammu, his advisor Isimud and a variety of subservient creatures, such as the gatekeeper Lahmu, also lived in the abzu.

Ap (áp-) is the Vedic Sanskrit term for “water”, in Classical Sanskrit occurring only in the plural, āpas (sometimes re-analysed as a thematic singular, āpa-), whence Hindi āp. The term is from PIE hxap “water”. The Indo-Iranian word survives also, as the Persian word for water, Āb, e.g. in Punjab (from panj-āb “five waters”).

Apas (āpas) is the Avestan language term for “the waters”, which – in its innumerable aggregate states – is represented by the Apas, the hypostases of the waters.

In both Avestan and Vedic Sanskrit texts, the waters—whether as waves or drops, or collectively as streams, pools, rivers or wells—are represented by the Apas, the group of divinities of the waters. The identification of divinity with element is complete in both cultures.

Here, a similarity can be seen between the concept of ‘Ap’(Waters/River) and the Sumerian ‘Ab’(Ocean), which is a language that is widely believed to be a language isolate. In archaic ablauting contractions, the laryngeal of the PIE root remains visible in Vedic Sanskrit, e.g. pratīpa- “against the current”, from *proti-hxp-o-.

In the Rigveda, several hymns are dedicated to “the waters” (āpas): 7.49, 10.9, 10.30, 10.47. In the oldest of these, 7.49, the waters are connected with the draught of Indra. Agni, the god of fire, has a close association with water and is often referred to as Apām Napāt “offspring of the waters”. The female deity Apah is the presiding deity of Purva Ashadha (The former invincible one) asterism in Vedic astrology

In Hindu philosophy, the term refers to water as an element, one of the Panchamahabhuta, or “five great elements”. In Hinduism, it is also the name of the deva Varuna a personification of water, one of the Vasus in most later Puranic lists.

In the myth and folklore of the Near East and Europe, Abyzou is the name of a female demon. Abyzou was blamed for miscarriages and infant mortality and was said to be motivated by envy, as she herself was infertile.

In the Jewish tradition she is identified with Lilith, in Coptic Egypt with Alabasandria, and in Byzantine culture with Gylou, but in various texts surviving from the syncretic magical practice of antiquity and the early medieval era she is said to have many or virtually innumerable names.

Abyzou is pictured on amulets with fish- or serpent-like attributes. Her fullest literary depiction is the compendium of demonology known as the Testament of Solomon, dated variously by scholars from as early as the 1st century AD to as late as the 4th.

A.A. Barb connected Abyzou and similar female demons to the Sumerian myth of primeval Sea. Barb argued that although the name “Abyzou” appears to be a corrupted form of the Greek word abyssos (“the abyss”), the Greek itself was borrowed from Assyrian Apsu or Sumerian Abzu, the undifferentiated sea from which the world was created in the Sumerian belief system, equivalent to Babylonian Tiamat, or Hebrew Tehom in the Book of Genesis.

The entity Sea was originally bi- or asexual, later dividing into male Abzu (fresh water) and female Tiamat (salt water). The female demons among whom Lilith is the best-known are often said to have come from the primeval sea.

In classical Greece, female sea monsters that combine allure and deadliness may also derive from this tradition, including the Gorgons (who were daughters of the old sea god Phorcys), Sirens, Harpies, and even water nymphs and Nereids.

In the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures, the word Abyssos is treated as a noun of feminine grammatical gender, even though Greek nouns ending in -os are typically masculine. Abyssos is equivalent in meaning to Mesopotamian Abzu as the dark chaotic sea before Creation.

The word also appears in the Christian scriptures, occurring six times in the Book of Revelation, where it is conventionally translated not as “the deep” but as “the bottomless pit” of Hell. Barb argues that in essence the Sumerian Abzu is the “grandmother” of the Christian Devil.

Nut and Geb (Hebat)

The Ennead (meaning a collection of nine things) was a group of nine deities in Egyptian mythology. The Ennead were worshipped at Heliopolis (Egyptian: Aunu, “place of pillars”) and consisted of the god Atum, his children Shu and Tefnut, their children Geb and Nut and their children Osiris, Isis, Set and Nephthys.

The creation account of Heliopolis relates that from the primeval waters represented by Nun, a mound appeared on which the self-begotten deity Atum sat. Bored and alone, Atum spat or, according to other stories, masturbated, producing Shu, representing the air and Tefnut, representing moisture.

Some versions however have Atum – identified with Ra – father Shu and Tefnut with Iusaaset, who is accordingly sometimes described as a “shadow” in this pesedjet.

In turn, Shu and Tefnut mated and brought forth Geb, representing the earth, and Nut, representing the nighttime sky. Because of their initial closeness, Geb and Nut engaged in continuous copulation until Shu separated them, lifting Nut into her place in the sky. The children of Geb and Nut were the sons Osiris and Set and the daughters Isis and Nephthys, which in turn formed couples.

In the Heliopolitan Ennead (a group of nine gods created in the beginning by the one god Atum or Ra), Geb is the husband of Nut, the sky or visible daytime and nightly firmament, the son of the earlier primordial elements Tefnut (moisture) and Shu (‘emptiness’), and the father to the four lesser gods of the system – Osiris, Seth, Isis and Nephthys.

In this context, Geb was believed to have originally been engaged in sex with Nut and had to be separated from her by Shu, god of the air. Consequently, in mythological depictions, Geb was shown as a man reclining, sometimes with his phallus still pointed towards Nut.

Nut and her brother, Geb, may be considered enigmas in the world of mythology. In direct contrast to most other mythologies which usually develop a sky father associated with an Earth mother (or Mother Nature), she personified the sky and he the Earth.

Nut, or Neuth, also spelled Nuit or Newet) was the goddess of the sky in the Ennead of Egyptian mythology. Nut appears in the creation myth of Heliopolis which involves several goddesses who play important roles: Tefnut (Tefenet) is a personification of moisture, who mated with Shu (Air) and then gave birth to Sky as the goddess Nut, who mated with her brother Earth, as Geb.

From the union of Geb and Nut came, among others, the most popular of Egyptian goddesses, Isis, the mother of Horus, whose story is central to that of her brother-husband, the resurrection god Osiris. Osiris is killed by his brother Seth and scattered over the Earth in 14 pieces which Isis gathers up and puts back together. Osiris then climbs a ladder into his mother Nut for safety and eventually becomes king of the dead.

A huge cult developed about Osiris that lasted well into Roman times. Isis was her husband’s queen in the underworld and the theological basis for the role of the queen on earth. It can be said that she was a version of the great goddess Hathor. Like Hathor she not only had death and rebirth associations, but was the protector of children and the goddess of childbirth.

She was seen as a star-covered nude woman arching over the earth, or as a cow. Originally, Nut was said to be laying on top of Geb (Earth) and continually having intercourse. During this time she birthed four or five children: Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys, and sometimes Horus.

Nut was the goddess of the sky and all heavenly bodies, a symbol of protecting the dead when they enter the after life. According to the Egyptians, during the day, the heavenly bodies—such as the sun and moon – would make their way across her body. Then, at dusk, they would be swallowed, pass through her belly during the night, and be reborn at dawn.

Nut is also the barrier separating the forces of chaos from the ordered cosmos in the world. She was pictured as a woman arched on her toes and fingertips over the earth; her body portrayed as a star-filled sky. Nut’s fingers and toes were believed to touch the four cardinal points or directions of north, south, east, and west.

Nut is a daughter of Shu and Tefnut. She is Geb’s sister. Her name is translated to mean ‘sky’ and she is considered one of the oldest deities among the Egyptian pantheon, with her origin being found on the creation story of Heliopolis.

Nut was originally the goddess of the nighttime sky, but eventually became referred to as simply the sky goddess. Her headdress was the hieroglyphic of part of her name, a pot, which may also symbolize the uterus.

Mostly depicted in nude human form, Nut was also sometimes depicted in the form of a cow whose great body formed the sky and heavens, a sycamore tree, or as a giant sow, suckling many piglets (representing the stars).

As time progressed, the deity became more associated with the habitable land of Egypt and also as one of its early rulers. As a chthonic deity he (like Min) became naturally associated with the underworld and with vegetation – barley being said to grow upon his ribs – and was depicted with plants and other green patches on his body.

His association with vegetation, and sometimes with the underworld and royalty brought Geb the occasional interpretation that he was the husband of Renenutet, a minor goddess of the harvest and also mythological caretaker (the meaning of her name is “nursing snake”) of the young king in the shape of a cobra, who herself could also be regarded as the mother of Nehebkau, a primeval snake god associated with the underworld. He is also equated by classical authors as the Greek Titan Cronus.

Geb was the Egyptian god of the Earth and a member of the Ennead of Heliopolis. It was believed in ancient Egypt that Geb’s laughter were earthquakes and that he allowed crops to grow.

The name was pronounced as such from the Greek period onward and was formerly erroneously read as Seb or as Keb. The original Egyptian was perhaps “Gebeb”/”Kebeb”. It was spelled with either initial -g- (all periods), or with -k-point (gj).

The latter initial root consonant occurs once in the Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts, more often in 21st Dynasty mythological papyri as well as in a text from the Ptolemaic tomb of Petosiris at Tuna el-Gebel or was written with initial hard -k-, as e.g. in a 30th Dynasty papyrus text in the Brooklyn Museum dealing with descriptions of and remedies against snakes.

The oldest representation in a fragmentary relief of the god, was as an anthropomorphic bearded being accompanied by his name, and dating from king Djoser’s reign, 3rd Dynasty, and was found in Heliopolis. In later times he could also be depicted as a ram, a bull or a crocodile (the latter in a vignette of the Book of the Dead of the lady Heryweben in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

Geb was frequently described mythologically as father of snakes (one of the names for snake was s3-t3 – “son of the earth”). In a Coffin Texts spell Geb was described as father of the snake Nehebkau. In mythology Geb also often occurs as a primeval divine king of Egypt from whom his son Osiris and his grandson Horus inherited the land after many contendings with the disruptive god Set, brother and killer of Osiris.

Geb could also be regarded as personified fertile earth and barren desert, the latter containing the dead or setting them free from their tombs, metaphorically described as “Geb opening his jaws”, or imprisoning those there not worthy to go to the fertile North-Eastern heavenly Field of Reeds. In the latter case, one of his otherworldly attributes was an ominous jackal-headed stave (called wsr.t) rising from the ground unto which enemies could be bound.

As time progressed, the deity became more associated with the habitable land of Egypt and also as one of its early rulers. As a chthonic deity he (like Min) became naturally associated with the underworld and with vegetation – barley being said to grow upon his ribs – and was depicted with plants and other green patches on his body.

His association with vegetation, and sometimes with the underworld and royalty brought Geb the occasional interpretation that he was the husband of Renenutet, a minor goddess of the harvest and also mythological caretaker (the meaning of her name is “nursing snake”) of the young king in the shape of a cobra, who herself could also be regarded as the mother of Nehebkau, a primeval snake god associated with the underworld. He is also equated by classical authors as the Greek Titan Cronus.

Nammu

It is thought that female deities are older than male ones in Mesopotamia and Tiamat may have begun as part of the cult of Nammu, also Namma (spelled ideographically NAMMA = ENGUR), a primeval goddess, corresponding to Tiamat in Babylonian mythology, a female principle of a watery creative force, with equally strong connections to the underworld, which predates the appearance of Ea-Enki.

Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the Goddess sea (Engur), also known as the Abzu, that gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first gods, representing the Apsu, the fresh water ocean that the Sumerians believed lay beneath the earth, the source of life-giving water and fertility in a country with almost no rainfall.

Reay Tannahill in Sex in History (1980) singled out Nammu as the “only female prime mover” in the cosmogonic myths of antiquity. Nammu is the goddess who “has given birth to the great gods”. It is she who has the idea of creating mankind, and she goes to wake up Enki, characterized as the lord of the Abzu, the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth, when he is asleep in the Apsu, so that he may set the process going.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

According to the Neo-Sumerian mythological text Enki and Ninmah, Nammu was, as the watery creative force, said to preexist Ea-Enki and was the mother of Enki, while An was his father. Enki was the grandson of Abzu.

Nammu is not well attested in Sumerian mythology. She may have been of greater importance prehistorically, before Enki took over most of her functions. An indication of her continued relevance may be found in the theophoric name of Ur-Nammu (ca. 2047-2030 BC short chronology), the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule.

Enki

Enki is a god in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water.” In Sumerian E-A means “the house of water”, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

Enki was considered a god of life and replenishment, and was often depicted with two streams of water emanating from his shoulders, one the Tigris, the other the Euphrates.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

Enki was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation (Nudimmud: nu, likeness, dim mud, make beer). Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, he was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization.

Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40,” occasionally referred to as his “sacred number.”

Alongside him were trees symbolising the female and male aspects of nature, each holding the female and male aspects of the ‘Life Essence’, which he, as apparent alchemist of the gods, would masterfully mix to create several beings that would live upon the face of the earth.

The main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”"), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu.

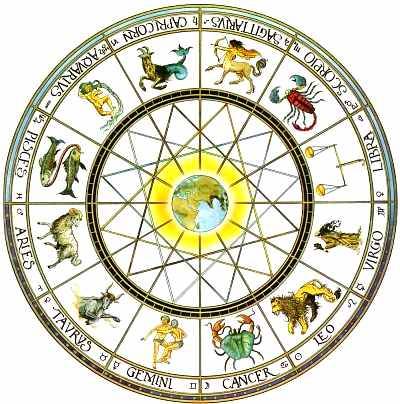

He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp. His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus).

He was accompanied by an attendant Isimud. He was also associated with the planet Mercury in the Sumerian astrological system. His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, very similar to the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine.

Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth. Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water’”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

The cosmogenic myth common in Sumer was that of the hieros gamos, a sacred marriage where divine principles in the form of dualistic opposites came together as male and female to give birth to the cosmos. In the epic Enki and Ninhursag, Enki, as lord of Ab or fresh water (also the Sumerian word for semen), is living with his wife in the paradise of Dilmun.

Dilmun was identified with Bahrein, whose name in Arabic means “two seas”, where the fresh waters of the Arabian aquifer mingle with the salt waters of the Persian Gulf. This mingling of waters was known in Sumerian as Nammu, and was identified as the mother of Enki.

Enki and Ninhursag and the Creation of Life and Sickness

Enki and the Making of Man

Confuser of languages

Enki and the Deluge

Enki and Inanna

Yahwe

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael), with Ia. Jean Bottero (1952) and others suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea, Enki’s Akkadian name, associating the Canaanite theonym Yahu, and ultimately Hebrew YHWH.

This hypothesis is dismissed by some scholars as erroneous, based on a mistaken cuneiform reading, but academic debate continues. Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic Yamm (sea), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw, or Ya’a.

Allah

Allah is the Arabic word for God (literally ‘the God’, as the initial “Al-” is the definite article). It is used mainly by Muslims to refer to God in Islam, Arab Christians, and often, albeit not exclusively, by Bahá’ís, Arabic-speakers, Indonesian and Maltese Christians, and Mizrahi Jews. Christians and Sikhs in Malaysia also use and have used the word to refer to God.

The term Allāh is derived from a contraction of the Arabic definite article al- “the” and ilāh “deity, god” to al-lāh meaning “the [sole] deity, God”. Cognates of the name “Allāh” exist in other Semitic languages, including Hebrew and Aramaic.

The name was previously used by pagan Meccans as a reference to a creator deity, possibly the supreme deity in pre-Islamic Arabia. In pre-Islamic Arabia amongst pagan Arabs, Allah was not considered the sole divinity, having associates and companions, sons and daughters–a concept that was deleted under the process of Islamization.

The name Allah was used by Nabataeans in compound names, and was found throughout the entire region of the Nabataean kingdom. From Nabataean inscriptions, Allah seems to have been regarded as a “High and Main God”, while other deities were considered to be mediators before Allah and of a second status, which was the same case of the worshipers at the Kaaba temple at Mecca.

Many inscriptions containing the name Allah have been discovered in Northern and Southern Arabia as early as the 5th century B.C., including Lihyanitic, Thamudic and South Arabian inscriptions.

The name Allah or Alla was found in the Epic of Atrahasis engraved on several tablets dating back to around 1700 BC in Babylon, which showed that he was being worshipped as a high deity among other gods who were considered to be his brothers but taking orders from him.

Dumuzid the Shepherd, a king of the 1st Dynasty of Uruk named on the Sumerian King List, was later over-venerated so that people started associating him with “Alla” and the Babylonian god Tammuz.

Ninhursag

Ninhursag is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the ‘true and great lady of heaven’ (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were ‘nourished by Ninhursag’s milk’.

Her hair is sometimes depicted in an omega shape, and she at times wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders, and not infrequently carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

Her symbol, resembling the Greek letter omega Ω, has been depicted in art from around 3000 BC, though more generally from the early second millennium. It appears on some boundary stones – on the upper tier, indicating her importance.

The omega symbol is associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor, and may represent a stylized womb. Hathor is at times depicted on a mountain, so it may be that the two goddesses are connected.

Nin-hursag means “lady of the sacred mountain” (from Sumerian NIN “lady” and ḪAR.SAG “sacred mountain, foothill”, possibly a reference to the site of her temple, the E-Kur (House of mountain deeps) at Eridu. She had many names including Ninmah (“Great Queen”); Nintu (“Lady of Birth”); Mamma or Mami (mother); Aruru, Belet-Ili (lady of the gods, Akkadian).

According to legend her name was changed from Ninmah to Ninhursag by her son Ninurta in order to commemorate his creation of the mountains. As Ninmenna, according to a Babylonian investiture ritual, she placed the golden crown on the king in the Eanna temple.

Some of the names above were once associated with independent goddesses (such as Ninmah and Ninmenna), who later became identified and merged with Ninhursag, and myths exist in which the name Ninhursag is not mentioned.

As the wife and consort of Enki she was also referred to as Damgulanna or Damkina (faithful wife). She had many epithets including shassuru or ‘womb goddess’, tabsut ili ‘midwife of the gods’, ‘mother of all children’ and ‘mother of the gods’. In this role she is identified with Ki in the Enuma Elish. She had shrines in both Eridu and Kish.

In the legend of Enki and Ninhursag, Ninhursag bore a daughter to Enki called Ninsar (“Lady Greenery”). Through Enki, Ninsar bore a daughter Ninkurra. Ninkurra, in turn, bore Enki a daughter named Uttu.

Enki then pursued Uttu, who was upset because he didn’t care for her. Uttu, on her ancestress Ninhursag’s advice buried Enki’s seed in the earth, whereupon eight plants (the very first) sprung up.

Enki, seeing the plants, ate them, and became ill in eight organs of his body. Ninhursag cured him, taking the plants into her body and giving birth to eight deities: Abu, Nintulla (Nintul), Ninsutu, Ninkasi, Nanshe (Nazi), Azimua, Ninti, and Enshag (Enshagag).

In the text ‘Creator of the Hoe’, she completed the birth of mankind after the heads had been uncovered by Enki’s hoe. In creation texts, Ninmah (another name for Ninhursag) acts as a midwife whilst the mother goddess Nammu makes different kinds of human individuals from lumps of clay at a feast given by Enki to celebrate the creation of humankind.

Creation of Life

A large number of myths about Enki have been collected from many sites, stretching from Southern Iraq to the Levantine coast. He figures in the earliest extant cuneiform inscriptions throughout the region and was prominent from the third millennium down to Hellenistic times.

The tale Enki and Ninhursag and the Creation of Life and Sickness share similarities to the Biblical story of the forbidden fruit, and repeats the story of how fresh water brings life to a barren land.

Enki, the Water-Lord then “caused to flow the ‘water of the heart” and having fertilised his consort Ninhursag, also known as Ki or Earth, after “Nine days being her nine months, the months of ‘womanhood’… like good butter, Nintu, the mother of the land, … like good butter, gave birth to Ninsar, (Lady Greenery)”.

Ninhursag relents and takes Enki’s Ab (water, or semen) into her body, and gives birth to gods of healing of each part of the body. Abu for the Jaw, Nintul for the Hip, Ninsutu for the tooth, Ninkasi for the mouth, Dazimua for the side, Enshagag for the Limbs. The last one, Ninti (Lady Rib), is also a pun on Lady Life, a title of Ninhursag herself.

The story thus symbolically reflects the way in which life is brought forth through the addition of water to the land, and once it grows, water is required to bring plants to fruit. It also counsels balance and responsibility, nothing to excess.