![]()

Thracian peltast, 5th–4th century BC.

![]()

The Odrysian kingdom in its maximum extent under Sitalces (431-424 BC).

![]()

Marble statue of a Dacian warrior surmounting the Arch of Constantine in Rome.

![]()

Dacian Draco as from Trajan’s Column

![]()

Tiridates I of Armenia (reign: 63 AD). Statue: Versailles, France

-

-

Languages

The Paleo-Balkan languages are the various Indo-European languages that were spoken in the Balkans in ancient times. Except for Greek and the language that developed into Albanian, they are all extinct, due to Hellenization, Romanization, Slavicization and Turkicization.

The following languages are reported to have been spoken on the Balkan Peninsula by Ancient Greek and Roman writers: Ancient Macedonian, Dacian, Illyrian languages, Liburnian, Messapic, Mysian, Paeonian, Phrygian, and Thracian.

Although these languages are all members of the Indo-European language family, the relationships between them are unknown. Classification of the languages spoken in the region is severely hampered by the fact that they are all scantily attested.

Furthermore, many of the individuals who have published studies on these languages have had strong patriotic or nationalistic interests, which compromises the scholarly value of their work.

The classification of Ancient Macedonian and its relationship to Greek are also under investigation, with solid sources pointing that Ancient Macedonian is in fact a variation of Doric Greek, but also the possibility of being only related through the local sprachbund.

Hellenic constitutes a branch of the Indo-European language family. The ancient languages that might have been most closely related to it, ancient Macedonian and Phrygian, are not well enough documented to permit detailed comparison. Among Indo-European branches with living descendants, Greek is often argued to have the closest genetic ties with Armenian and the Indo-Iranian languages.

The Proto-Greek language is the assumed last common ancestor of all known varieties of Greek, including Mycenaean, the classical Greek dialects (Attic-Ionic, Aeolic, Doric and Arcado-Cypriot), and ultimately Koine, Byzantine and modern Greek.

Some scholars would include the fragmentary ancient Macedonian language, either as descended from an earlier “Proto-Hellenic” language, or by definition including it among the descendants of Proto-Greek as a Hellenic language and/or a Greek dialect.

The unity of Proto-Greek would have ended as Hellenic migrants, speaking the predecessor of the Mycenaean language, entered the Greek peninsula either during the Neolithic period or the Bronze Age.

The evolution of Proto-Greek should be considered within the context of an early Paleo-Balkan sprachbund that makes it difficult to delineate exact boundaries between individual languages.

The characteristically Greek representation of word-initial laryngeals by prothetic vowels is shared by the Armenian language, which also shares other phonological and morphological peculiarities of Greek. The close relatedness of Armenian and Greek sheds light on the paraphyletic nature of the Centum-Satem isogloss.

The close similarities between Ancient Greek and Vedic Sanskrit suggest that both Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian were still quite similar to either late Proto-Indo-European, which would place the latter somewhere in the late 4th millennium BC.

Scholars are divergent in their views regarding the geographical origins of proto-Greek and when the first Greek-speakers arrived into the Greek peninsula. Vladimir I. Georgiev, for example, placed proto-Greek in northwestern Greece during the Late Neolithic period.

Eric Hamp, however, placed the first speakers of Greek and ancient Macedonian (“Helleno-Macedonian”) in the northeast coast of the Black Sea and its hinterlands who migrated to Greece through Anatolia during the Bronze Age.

In the field of archaeogenetics, Russel Gray and Quentin Atkinson, using computational methods derived from evolutionary biology, concluded that the divergence of Greco-Armenian from Proto-Indo-European occurred around 7300–7000 years ago (~5300–5000 BC) coinciding with the spread of agriculture from Asia Minor to Greece during the Neolithic period; Greek, specifically, developed into a separate linguistic lineage before 6000 years ago (before 4000 BC).

The Armenian language is an Indo-European language spoken by the Armenians. It is the official language of the Republic of Armenia and the self-proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. It has historically been spoken throughout the Armenian Highlands and today is widely spoken in the Armenian diaspora. It is of interest to linguists for its distinctive phonological developments within the Indo-European family of languages.

Linguists classify Armenian as an independent branch of the Indo-European language family. Armenian shares a number of major innovations with Greek, and some linguists group these two languages together with the Indo-Iranian family into a higher-level subgroup of Indo-European, which is defined by such shared innovations as the augment. More recently, others have proposed a Balkan grouping including Greek, Armenian, and Albanian.

The large percentage of loans from Iranian languages initially led linguists to erroneously classify Armenian as an Iranian language. The distinctness of Armenian was only recognized when Hübschmann (1875) used the comparative method to distinguish two layers of Iranian loans from the older Armenian vocabulary.

M. Austin (1942) concluded that there was an early contact between Armenian and Anatolian languages, based on what he considered common archaisms, such as the lack of a feminine and the absence of inherited long vowels. However, unlike shared innovations (or synapomorphies), the common retention of archaisms (or symplesiomorphy) is not necessarily considered evidence of a period of common isolated development.

Soviet linguist Igor Diakonov (1985) noted the presence in Old Armenian of what he calls a Caucasian substratum, identified by earlier scholars, consisting of loans from the Kartvelian and Northeast Caucasian languages such as Udi.

Noting that the Hurro-Urartian peoples inhabited the Armenian homeland in the second millennium b.c., Diakonov identifies in Armenian a Hurro-Urartian substratum of social, cultural, and animal and plant terms such as ałaxin “slave girl” ( ← Hurr. al(l)a(e)ḫḫenne), cov “sea” ( ← Urart. ṣûǝ “(inland) sea”), ułt “camel” ( ← Hurr. uḷtu), and xnjor “apple(tree)” ( ← Hurr. ḫinzuri).

Some of the terms he gives admittedly have an Akkadian or Sumerian provenance, but he suggests they were borrowed through Hurrian or Urartian. Given that these borrowings do not undergo sound changes characteristic of the development of Armenian from Proto-Indo-European, he dates their borrowing to a time before the written record but after the Proto-Armenian language stage.

Proto-Armenian is an earlier, unattested stage of the Armenian language that has been reconstructed by linguists. As Armenian is the only known language of its branch of the Indo-European languages, the comparative method cannot be used to reconstruct earlier stages.

Instead, a combination of internal reconstruction and external reconstruction, through reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European and other branches, has allowed linguists to piece together the earlier history of Armenian.

Because Proto-Armenian is not the common ancestor of several related languages, but of just a single language, there is no clear definition of the term. It is generally held to include a variety of ancestral stages of Armenian between the times of Proto-Indo-European up to the earliest attestations of Old Armenian. Thus, it is not a Proto-language in the strict sense, although the term “Proto-Armenian” has become common in the field regardless.

The earliest testimony of Armenian dates to the 5th century AD (the Bible translation of Mesrob Mashtots). The earlier history of the language is unclear and the subject of much speculation. It is clear that Armenian is an Indo-European language, but its development is opaque. In any case, Armenian has many layers of loanwords and shows traces of long language contact with Hurro-Urartian, Greek and Indo-Iranian.

The Proto-Armenian sound changes are varied and eccentric (such as *dw- yielding erk-), and in many cases uncertain. For this reason, Armenian was not immediately recognized as an Indo-European branch in its own right, and was assumed to be simply a very eccentric member of the Iranian languages before H. Hübschmann established its independent character in an 1874 publication.

Proto-Indo-European voiceless stops are aspirated in Proto-Armenian, a circumstance that gave rise to an extended version of the Glottalic theory, which postulates that this aspiration may have been sub-phonematic already in PIE. In certain contexts, these aspirated stops are further reduced to w, h or zero in Armenian (PIE *pots, Armenian otn, Greek pous “foot”; PIE treis, Armenian erekʿ, Greek treis “three”).

The Armenians according to Diakonoff, are then an amalgam of the Hurrians (and Urartians), Luvians and the Mushki. After arriving in its historical territory, Proto-Armenian would appear to have undergone massive influence on part the languages it eventually replaced. Armenian phonology, for instance, appears to have been greatly affected by Urartian, which may suggest a long period of bilingualism.

Graeco-Aryan (or Graeco-Armeno-Aryan) is a hypothetical clade within the Indo-European family, ancestral to the Greek language, the Armenian language, and the Indo-Iranian languages. Graeco-Aryan unity would have become divided into Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian by the mid 3rd millennium BC.

Conceivably, Proto-Armenian would have been located between Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian, consistent with the fact that Armenian shares certain features only with Indo-Iranian (the satem change) but others only with Greek (s > h).

Graeco-Armeno-Aryan has comparatively wide support among Indo-Europeanists for the Indo-European Homeland to be located in the Armenian Highland. Early and strong evidence was given by Euler’s 1979 examination on shared features in Greek and Sanskrit nominal flection.

Used in tandem with the Graeco-Armeno-Aryan hypothesis, the Armenian language would also be included under the label Aryano-Greco-Armenic, splitting into proto-Greek/Phrygian and “Armeno-Aryan” (ancestor of Armenian and Indo-Iranian).

In the context of the Kurgan hypothesis, Greco-Aryan is also known as “Late PIE” or “Late Indo-European” (LIE), suggesting that Greco-Aryan forms a dialect group which corresponds to the latest stage of linguistic unity in the Indo-European homeland in the early part of the 3rd millennium BC. By 2500 BC, Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian had separated, moving westward and eastward from the Pontic Steppe, respectively. Graeco-Aryan is invoked in particular in studies of comparative mythology, e.g. by West (1999) and Watkins (2001).

If Graeco-Aryan is a valid group, Grassmann’s law may have a common origin in Greek and Sanskrit. (Note, however, that Grassmann’s law in Greek postdates certain sound changes that happened only in Greek and not Sanskrit, which suggests that it cannot strictly be an inheritance from a common Graeco-Aryan stage. Rather, it is more likely an areal feature that spread across a then-contiguous Graeco-Aryan-speaking area after early Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian had developed into separate dialects but before they ceased being in geographic contact.)

Graeco-Armenian (also Helleno-Armenian) is the hypothetical common ancestor of the Greek and Armenian languages which postdates the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). Its status is comparable to that of the Italo-Celtic grouping: each is widely considered plausible without being accepted as established communis opinio.

The hypothetical Proto-Graeco-Armenian stage would need to date to the 3rd millennium BC, only barely differentiated from either late PIE or Graeco-Armeno-Aryan. The hypothesis originates with Pedersen (1924), who noted that the number of Greek-Armenian lexical cognates is greater than that of agreements between Armenian and any other Indo-European language.

Meillet (1925, 1927) further investigated morphological and phonological agreement, postulating that the parent languages of Greek and Armenian were dialects in immediate geographical proximity in the parent language.

Meillet’s hypothesis became popular in the wake of his Esquisse d’une grammaire comparée de l’arménien classique (1936). Solta (1960) does not go as far as postulating a Proto-Graeco-Armenian stage, but he concludes that considering both the lexicon and morphology, Greek is clearly the dialect most closely related to Armenian.

Hamp (1976:91) supports the Graeco-Armenian thesis, anticipating even a time “when we should speak of Helleno-Armenian” (meaning the postulate of a Graeco-Armenian proto-language).

Clackson (1994:202) is again more reserved, holding the evidence in favour of a positive Graeco-Armenian sub-group to be inconclusive and tends to include Armenian into a larger Graeco-Armeno-Aryan family.

Evaluation of the hypothesis is tied up with the analysis of the poorly attested Phrygian language. While Greek is attested from very early times, allowing a secure reconstruction of a Proto-Greek language dating to the late 3rd millennium, the history of Armenian is opaque. It is strongly linked with Indo-Iranian languages; in particular, it is a Satem language.

The earliest testimony of the Armenian language dates to the 5th century AD (the Bible translation of Mesrob Mashtots). The earlier history of the language is unclear and the subject of much speculation. It is clear that Armenian is an Indo-European language, but its development is opaque. In any case, Armenian has many layers of loanwords and shows traces of long language contact with Greek and Indo-Iranian.

Nakhleh, Warnow, Ringe, and Evans (2005) compared various phylogeny methods and found that five procedures (maximum parsimony, weighted and unweighted maximum compatibility, neighbor joining, and the widely criticized technique of Gray and Atkinson) support a Graeco-Armenian subgroup.

Graeco-Phrygian is a hypothetical branch of the Indo-European language family with two ‘child’ branches: Greek and Phrygian. Greek has also been variously grouped with Armenian (Graeco-Armenian; Graeco-Aryan), Ancient Macedonian (Graeco-Macedonian) and, more recently, Messapian.

Multiple or all of these, with the exception of Armenian, are sometimes (tentatively) classified under “Hellenic”; at other times, Hellenic is posited to consist of only Greek. Blažek (2005, p. 6) says that, in regard with the classification of these languages, their surviving texts—because of their scarcity and/or their nature—can’t be quantified.

Armeno-Phrygian is a term for a minority supported claim of hypothetical people who are thought to have lived in the Armenian Highland as a group and then have separated to form the Phrygians and the Mushki of Cappadocia.

It is also used for the language they are assumed to have spoken. It can also be used for a language branch including these languages, a branch of the Indo-European family or a sub-branch of the proposed Graeco-Armeno-Aryan or Armeno-Aryan branch.

Classification is difficult because little is known of Phrygian and virtually nothing of Mushki, while Proto-Armenian forms a subgroup with Hurro-Urartian, Greek, and Indo-Iranian. These subgroups are all Indo-European, with the exception of Hurro-Urartian.

Note that the name Mushki is applied to different peoples by different sources and at different times. It can mean the Phrygians (in Assyrian sources) or Proto-Armenians as well as the Mushki of Cappadocia, or all three, in which case it is synonymous with Armeno-Phrygian.

The Armenian hypothesis of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat, based on the Glottalic theory suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 4th millennium BC in the Armenian Highland. It is an Indo-Hittite model and does not include the Anatolian languages in its scenario.

The phonological peculiarities proposed in the Glottalic theory would be best preserved in the Armenian language and the Germanic languages, the former assuming the role of the dialect which remained in situ, implied to be particularly archaic in spite of its late attestation.

The Proto-Greek language would be practically equivalent to Mycenaean Greek and date to the 17th century BC, closely associating Greek migration to Greece with the Indo-Aryan migration to India at about the same time (viz., Indo-European expansion at the transition to the Late Bronze Age, including the possibility of Indo-European Kassites).

The Armenian hypothesis argues for the latest possible date of Proto-Indo-European (sans Anatolian), roughly a millennium later than the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis. In this, it figures as an opposite to the Anatolian hypothesis, in spite of the geographical proximity of the respective suggested Urheimaten, diverging from the timeframe suggested there by as much as three millennia.

The linguistic classification of the ancient Thracian language has long been a matter of contention and uncertainty, and there are widely varying hypotheses regarding its position among other Paleo-Balkan languages. It is not contested, however, that the Thracian languages were Indo-European languages which had acquired satem characteristics by the time they are attested.

The longer Thracian inscriptions that are known (if they are indeed examples of Thracian sentences and phrases, which has not been determined) are not apparently close to Baltic, Slavic, Albanian, or any other known language, and they have not been satisfactorily deciphered aside from perhaps a few words.

A Daco-Thracian grouping is widely held. The problem of the classification of Thracian can thus be seen as the wider problem of the classification of Daco-Thracian and its place within the Indo-European language family.

However, some paleo-linguists are not convinced that Dacian was a Northern branch of Thracian, and have sought to place Dacian on a separate branch rather than believing that Dacian diverged from Thracian/or Thracian diverged from Dacian (or both diverging from an immediate common ancestor).

In the 1950s, the Bulgarian linguist Vladimir I. Georgiev published his work which argued that Dacian and Albanian should be assigned to a language branch termed Daco-Mysian, Mysian (the term Mysian derives from the Daco-Thracian tribe known as the Moesi) being thought of as a transitional language between Dacian and Thracian.

Georgiev argued that Dacian and Thracian are different languages, with different phonetic systems, his idea being supported by the placenames, which end in -dava in Dacian and Mysian, as opposed to -para, in Thracian placenames.

A series of authors favors Georgiev’s view. Nevertheless, Polome hesitates to accept it. Crossland considers this seems to be a divergence of a Thraco-Dacian language into northern and southern groups of dialects, not as different as to rank as separate languages .

Thraco-Illyrian is a hypothesis that the Thraco-Dacian and Illyrian languages comprise a distinct branch of Indo-European. Thraco-Illyrian is also used as a term merely implying a Thracian-Illyrian interference, mixture or sprachbund, or as a shorthand way of saying that it is not determined whether a subject is to be considered as pertaining to Thracian or Illyrian. Downgraded to a geo-linguistic concept, these languages are referred to as Paleo-Balkan.

A hypothesis that Thracian (or in other scenarios, Daco-Thracian) and the Baltic languages or the Balto-Slavic languages form one branch of Indo-European has also been proposed. Here again due to the scanty evidence, though many close cognates exist between Balto-Slavic and Thracian, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that Thracian and Balto-Slavic or Thracian and Baltic (excluding Slavic in some scenarios) form one branch of Indo-European.

Sorin Mihai Olteanu, a Romanian linguist and Thracologist, recently proposed that the Thracian (as well as the Dacian) language was a centum language in its earlier period, and developed satem features over time. One of the arguments for this idea is that there are many close cognates between Thracian and Ancient Greek.

There are also substratum words in the Romanian language that are cited as evidence of the genetic relationship of the Thracian language to ancient Greek and the Ancient Macedonian language (the extinct language or Greek dialect of ancient Macedon). The Greek language itself may be grouped with the Phrygian language and Armenian language, both of which have been grouped with Thracian in the past.

As in the case with Albanian and Balto-Slavic, there is no compelling evidence that Thracian and Greek (or Daco-Thracian and Greco-Macedonian) share a close common ancestor.

People

The Dacians were an Indo-European people, part of or related to the Thracians. The Dacians spoke the Dacian language, believed to have been closely related to Thracian, but were somewhat culturally influenced by the neighbouring Scythians and by the Celtic invaders of the 4th century BC.

Dacians were the ancient inhabitants of Dacia, located in the area in and around the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. This area includes the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine, Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary and Southern Poland.

The Thracians (Ancient Greek: Θρᾷκες Thrāikes, Latin: Thraci) were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting a large area in Central and Southeastern Europe. They were bordered by the Scythians to the north, the Celts and the Illyrians to the west, the Ancient Greeks to the south and the Black Sea to the east. They spoke the Thracian language – a scarcely attested branch of the Indo-European language family. The study of Thracians and Thracian culture is known as Thracology.

In Greek mythology, Thrax (by his name simply the quintessential Thracian) was regarded as one of the reputed sons of the god Ares. In the Alcestis, Euripides mentions that one of the names of Ares himself was “Thrax” since he was regarded as the patron of Thrace (his golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia in Thrace).

One notable cult that is attested from Thrace to Moesia and Scythia Minor is that of the “Thracian horseman”, also known as the “Thracian Heros”, at Odessos (Varna) attested by a Thracian name as Heros Karabazmos, a god of the underworld usually depicted on funeral statues as a horseman slaying a beast with a spear. Some think that the Greek god Dionysus evolved from the Thracian god Sabazios.

The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records. Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts of material culture. Leo Klejn identifies proto-Thracians with the multi-cordoned ware culture that was pushed away from Ukraine by the advancing timber grave culture.

The Multi-cordoned Ware culture (also known as Mnogovalikovaya (MVK), Multiple-Relief-band Ware culture, and Babyno culture) is an archaeological culture of the Middle Bronze Age (22nd-18th centuries b.c.).

Tribes of this culture inhabited an area stretching from the Don to Moldavia, including Dnieper Ukraine, Right-bank Ukraine, and part of the modern Ternopil oblast. It was bordered by the Volga to the east. The culture succeeded the western Catacomb culture (ca. 2800–2200 BC), a group of related cultures in the early Bronze Age occupying essentially what is present-day Ukraine.

The Catacomb culture culture was the first to introduce corded pottery decorations into the steppes and shows a profuse use of the polished battle axe, providing a link to the West. Parallels with the Afanasevo culture, including provoked cranial deformations, provide a link to the East. It was preceded by the Yamna culture. The Catacomb culture in the Pontic steppe was succeeded by the Srubna culture from ca. the 17th century BC.

The linguistic composition of the Catacomb culture is unclear. Within the context of the Kurgan hypothesis expounded by Marija Gimbutas, an Indo-European component is hard to deny, particularly in the later stages. Placing the ancestors of the Greek, Armenian and Paleo-Balkan dialects here is tempting, as it would neatly explain certain shared features.

More recently, the Ukrainian archaeologist V. Kulbaka has argued that the Late Yamna cultures of ca. 3200–2800 BC, esp. the Budzhak, Starosilsk, and Novotitarovka groups, might represent the Greek-Armenian-“Aryan”(=Indo-Iranian) ancestors (Graeco-Aryan, Graeco-Armenian), and the Catacomb culture that of the “unified” (to ca. 2500 BC) and then “differentiated” Indo-Iranians.

Grigoryev’s (1998) version of the Armenian hypothesis connects Catacomb culture with Indo-Aryans, because catacomb burial ritual had roots in South-Western Turkmenistan from the early 4th millennium (Parkhai cemetery). The same opinion is supported by Leo Klejn in his various publications.

The Multi-cordoned Ware culture was overlain, assimilated, and eventually pushed out by the Timber grave culture (Srubnaya) (ca. 2000-1800 b.c.) which resulted in migration of its bearers into the Balkans who advanced further to the south, to the territory of Greece. Leo Klejn identifies its bearers with the early Thracians. Others attach the culture to the Proto-Phrygians/Bryges and Proto-Armenians (Mushki).

Two different groups are called Muški in the Assyrian sources (Diakonoff 1984:115), one from the 12th to 9th centuries, located near the confluence of the Arsanias and the Euphrates (“Eastern Mushki”), and the other in the 8th to 7th centuries, located in Cappadocia and Cilicia (“Western Mushki”). Assyrian sources identify the Western Mushki with the Phrygians, while Greek sources clearly distinguish between Phrygians and Moschoi.

Identification of the Eastern with the Western Mushki is uncertain, but it is of course possible to assume a migration of at least part of the Eastern Mushki to Cilicia in the course of the 10th to 8th centuries, and this possibility has been repeatedly suggested, variously identifying the Mushki as speakers of a Georgian, Armenian or Anatolian idiom.

The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture notes that “the Armenians according to Diakonoff, are then an amalgam of the Hurrian (and Urartians), Luvians and the Proto-Armenian Mushki (or Armeno-Phrygians) who carried their IE language eastwards across Anatolia.”

The Srubna culture (also English: Timber-grave culture), was a Late Bronze Age (18th–12th centuries BC) culture. The name comes from Russian cруб (srub), “timber framework”, from the way graves were constructed. Animal parts were buried with the body.

The Srubna culture is a successor to the Yamna culture (Pit Grave culture) and the Poltavka culture. It occupied the area along and above the north shore of the Black Sea from the Dnieper eastwards along the northern base of the Caucasus to the area abutting the north shore of the Caspian Sea, west of the Ural Mountains to come up against the domain of the approximately contemporaneous and somewhat related Andronovo culture.

The economy was mixed agriculture and livestock breeding. The historical Cimmerians have been suggested as descended from this culture. The Srubna culture is succeeded by Scythians and Sarmatians in the 1st millennium BC, and by Khazars and Kipchaks in the first millennium AD.

Poltavka culture, 2700—2100 BC, an early to middle Bronze Age archaeological culture of the middle Volga from about where the Don-Volga canal begins up to the Samara bend, with an easterly extension north of present Kazakhstan along the Samara River valley to somewhat west of Orenburg.

It is like the Catacomb culture preceded by the Yamna culture, while succeeded by the Sintashta culture. It seems to be seen as an early manifestation of the Srubna culture. There is evidence of influence from the Maykop culture to its south.

The only real things that distinguish it from the Yamna culture are changes in pottery and an increase in metal objects. Tumulus inhumations continue, but with less use of ochre. It was preceded by the Yamna culture and succeeded by the Srubna and Sintashta culture. It is presumptively early Indo-Iranian (Proto-Indo-Iranian).

The Yamna culture (“Pit [Grave] Culture”, from Russian/Ukrainian яма, “pit”) is a late copper age/early Bronze Age culture of the Southern Bug/Dniester/Ural region (the Pontic steppe), dating to the 36th–23rd centuries BC. The name also appears in English as Pit Grave Culture or Ochre Grave Culture.

The culture was predominantly nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers and a few hillforts. The earliest remains in Eastern Europe of a wheeled cart were found in the “Storozhova mohyla” kurgan (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, excavated by Trenozhkin A.I.) associated with the Yamna culture.

It is said to have originated in the middle Volga based Khvalynsk culture and the middle Dnieper based Sredny Stog culture. It was preceded by the Sredny Stog culture, Khvalynsk culture and Dnieper-Donets culture, while succeeded in its western range by the Catacomb culture and by the Poltavka culture and the Srubna culture in the east.

The Yamna culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas. It is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, along with the preceding Sredny Stog culture, now that archaeological evidence of the culture and its migrations has been closely tied to the evidence from linguistics.

The Sredny Stog culture is a pre-kurgan archaeological culture, named after the Russian term for the Dnieper river islet of Seredny Stih, Ukraine, where it was first located, dating from the 5th millennium BC.

It was situated across the Dnieper river on both its shores, with sporadic settlements to the west and east. One of the best known sites associated with this culture is Dereivka, located on the right bank of the Omelnik, a tributary of the Dnieper, and is the most impressive site within the Sredny Stog culture complex, being about 2,000 square meters in area.

The Sredny Stog culture seems to have had contact with the agricultural Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the west and was a contemporary of the Khvalynsk culture. In its three largest cemeteries, Alexandria (39 individuals), Igren (17) and Dereivka (14), evidence of inhumation in flat graves (ground level pits) has been found.

This parallels the practise of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, and is in contrast with the later Yamna culture, which practiced tumuli burials, according to the Kurgan hypothesis.

In Sredny Stog culture, the deceased were laid to rest on their backs with the legs flexed. The use of ochre in the burial was practiced, as with the kurgan cultures. For this and other reasons, Yuri Rassamakin suggests that the Sredny Stog culture should be considered as an areal term, with at least four distinct cultural elements co-existing inside the same geographical area.

The expert Dmytro Telegin has divided the chronology of Sredny Stog into two distinct phases. Phase II (ca. 4000–3500 BC) used corded ware pottery which may have originated there, and stone battle-axes of the type later associated with expanding Indo-European cultures to the West. Most notably, it has perhaps the earliest evidence of horse domestication (in phase II), with finds suggestive of cheek-pieces (psalia).

In the context of the modified Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas, this pre-kurgan archaeological culture could represent the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language. The culture ended at around 3500 BC, when Yamna culture expanded westward replacing Sredny Stog, and coming into direct contact with the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the western Ukraine.

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (ca. 4800 to 3000 BC) in Eastern Europe. It extends from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of some 350,000 km2(140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of some 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kiev in the northeast to Brasov in the southwest).

The majority of Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys. During the Middle Trypillia phase (ca. 4000 to 3500 BC), populations belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as 1,600 structures.

The roots of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture can be found in the Starčevo-Körös-Criș and Vinča cultures of the 6th to 5th millennia, with additional influence from the Bug-Dniester culture (6500-5000 BC).

During the early period of its existence (in the 5th millennium BC), the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was also influenced by the Linear Pottery culture from the north, and by the Boian-Giulesti culture from the south. Through colonization and acculturation from these other cultures, the formative Precucuteni/Trypillia A culture was established.

Over the course of the fifth millennium, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture expanded from its ‘homeland’ in the Prut-Siret region along the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into the basins and plains of the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers of central Ukraine. Settlements also developed in the southeastern stretches of the Carpathian Mountains, with the materials known locally as the Ariuşd culture.

Most of the settlements were located close to rivers, with fewer settlements located on the plateaus. Most early dwellings took the form of pit houses, though they were accompanied by an ever-increasing incidence of above-ground clay houses. The floors and hearths of these structures were made of clay, and the walls of clay-plastered wood or reeds. Roofing was made of thatched straw or reeds.

A 2010 study analyzed mtDNA recovered from Cucuteni-Trypillian human osteological remains found in the Verteba Cave (on the bank of the Siret river, Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine). It revealed that seven of the individuals whose remains was analysed belonged to the pre-HV branch of the R haplogroup, two to haplogroup HV, two to haplogroup H, one to haplogroup J, and one to T4 haplogroup, the latter also being the oldest sample of the set.

The authors conclude that the population living around Verteba Cave was fairly heterogenous, but that the wide chronological age of the specimens might indicate that the heterogeneity might have been due to natural population flow during this timeframe. The authors also link the pre-HV and HV/V haplogroups with European Paleolithic populations, and consider the T and J haplogroups as hallmarks of Neolithic demic intrusions from the South-East (the North-Pontic region) rather than from the West (i.e. the Linear Pottery culture).

Old Europe is a term coined by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas to describe what she perceived as a relatively homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture in southeastern Europe located in the Danube River valley.

Old Europe, or Neolithic Europe, refers to the time between the Mesolithic and Bronze Age periods in Europe, roughly from 7000 BC (the approximate time of the first farming societies in Greece) to ca. 1700 BC (the beginning of the Bronze Age in northwest Europe).

The duration of the Neolithic varies from place to place: in southeast Europe it is approximately 4000 years (i. e., 7000–3000 BC); in North-West Europe it is just under 3000 years (ca. 4500–1700 BC).

Marija Gimbutas investigated the Neolithic period in order to understand cultural developments in settled village culture in the southern Balkans, which she characterized as peaceful, matrilineal, and possessing a goddess-centered religion.

In contrast, she characterizes the later Indo-European influences as warlike, nomadic, and patrilineal. Using evidence from pottery and sculpture, and combining the tools of archaeology, comparative mythology, linguistics, and, most controversially, folkloristics, Gimbutas invented a new interdisciplinary field, archaeomythology.

In historical times, some ethnonyms are believed to correspond to Pre-Indo-European peoples, assumed to be the descendants of the earlier Old European cultures: the Pelasgians, Minoans, Leleges, Iberians, Etruscans and Basques.

Two of the three pre-Greek peoples of Sicily, the Sicans and the Elymians, may also have been pre-Indo-European. The term “Pre-Indo-European” is sometimes extended to refer to Asia Minor and Central Asia, in which case the Hurrians and Urartians are sometimes included.

How many Pre-Indo-European languages existed is not known. Nor is it known whether the ancient names of peoples descended from the pre-ancient population, actually referred to speakers of distinct languages.

Marija Gimbutas (1989), observing a unity of symbols marked especially on pots, but also on other objects, concluded that there may have been a single language spoken in Old Europe. She thought that decipherment would have to wait for the discovery of bilingual texts.

There is consensus that agricultural technology and the main breeds of animals and plants which are farmed entered Europe from somewhere in the area of the Fertile Crescent and specifically the Levant region from the Sinai to Southern Anatolia.

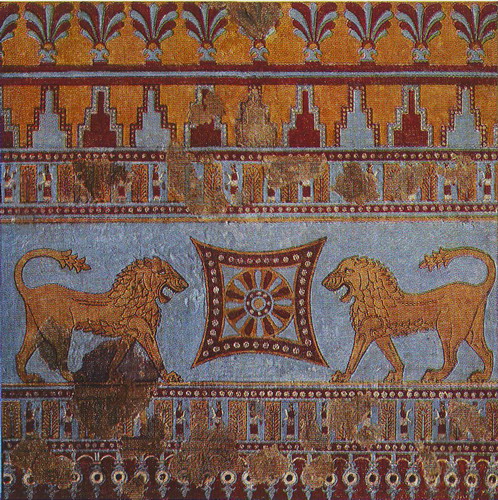

The Maykop culture (also spelled Maikop), ca. 3700 BC—3000 BC, was a major Bronz Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia.

It extends along the area from the Taman Peninsula at the Kerch Strait to near the modern border of Dagestan and southwards to the Kura River. The culture takes its name from a royal burial found in Maykop kurgan in the Kuban River valley.

New data revealed the similarity of artifacts from the Maykop culture with those found recently in the course of excavations of the ancient city of Tell Khazneh in northern Syria, the construction of which dates back to 4000 BC.

In the south it borders the approximately contemporaneous Kura-Araxes culture (3500—2200 BC), which extends into eastern Anatolia and apparently influenced it. To the north is the Yamna culture, including the Novotitorovka culture (3300—2700), which it overlaps in territorial extent. It is contemporaneous with the late Uruk period in Mesopotamia.

The Kuban River is navigable for much of its length and provides an easy water-passage via the Sea of Azov to the territory of the Yamna culture, along the Don and Donets River systems. The Maykop culture was thus well-situated to exploit the trading possibilities with the central Ukraine area.

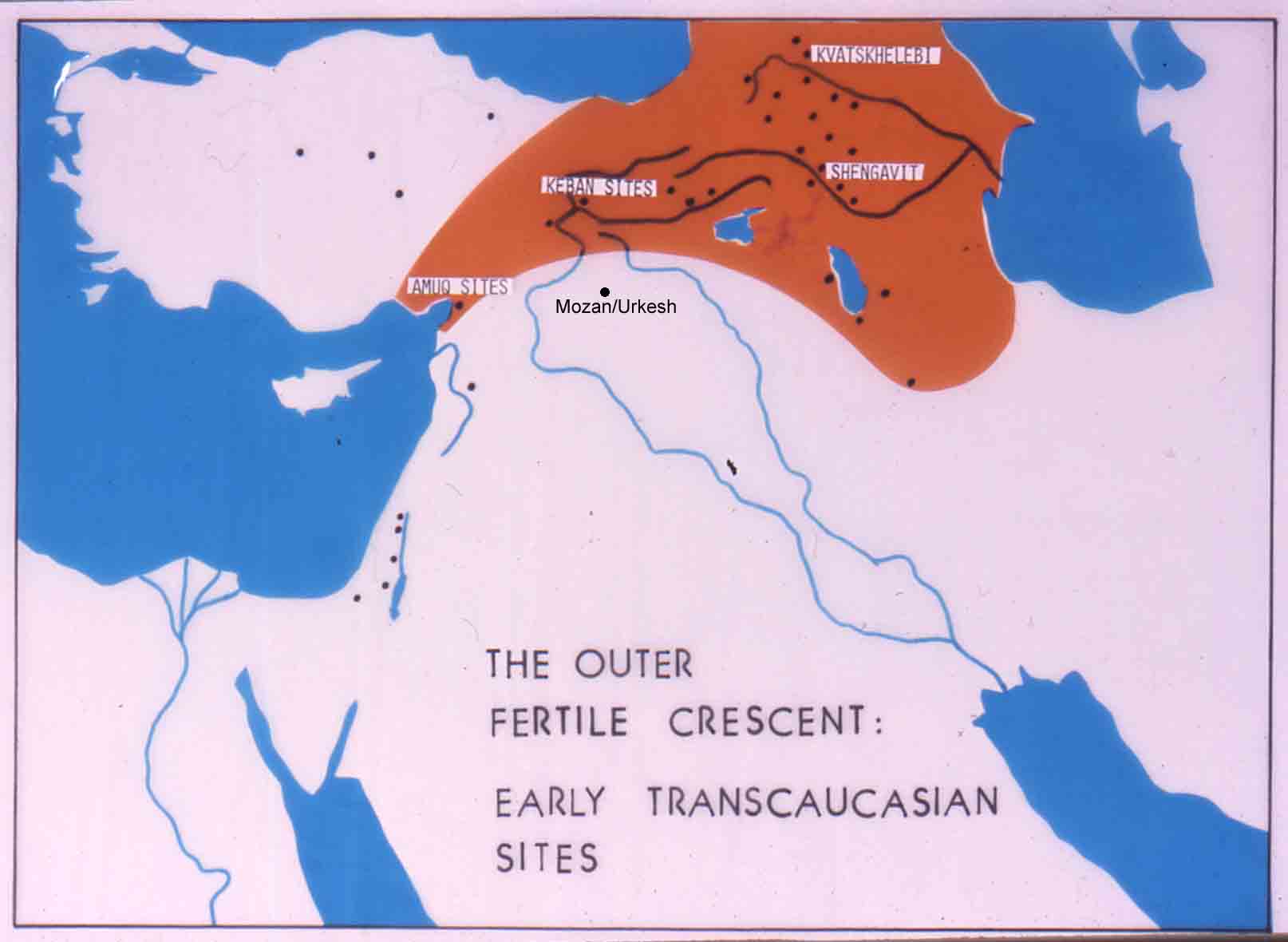

The Kura–Araxes culture or the early trans-Caucasian culture was a civilization that existed from 3400 BC until about 2000 BC, which has traditionally been regarded as the date of its end, but it may have disappeared as early as 2600 or 2700 BC. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain.

The name of the culture is derived from the Kura and Araxes river valleys. Its territory corresponds to parts of modern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Dagestan, Georgia, Ingushetia and North Ossetia. It may have given rise to the later Khirbet Kerak ware culture found in Syria and Canaan after the fall of the Akkadian Empire.

Hurrian and Urartian elements are quite probable, as are Northeast Caucasian ones. Some authors subsume Hurrians and Urartians under Northeast Caucasian as well as part of the Alarodian theory. The presence of Kartvelian languages was also highly probable. Influences of Semitic languages and Indo-European languages are also highly possible, though the presence of the languages on the lands of the Kura–Araxes culture is more controversial.

The Leyla-Tepe culture is a culture of archaeological interest from the Chalcolithic era. Its population was distributed on the southern slopes of the Central Caucasus (modern Azerbaijan, Agdam District), from 4350 until 4000 B.C.

Monuments of the Leyla-Tepe were first located in the 1980s by I.G. Narimanov, a Soviet archaeologist. Recent attention to the monuments has been inspired by the risk of their damage due to the construction of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline and the South Caucasus pipeline.

The Shulaveri-Shomu culture, a Late Neolithic/Eneolithic culture that existed on the territory of present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Armenian Highlands, is one of the earliest known prehistoric culture of the central Transcaucasus region, carbon-dated to roughly 6000 – 4000 BC. It is thought to be one of the earliest known Neolithic cultures.

The Shulaveri-Shomu culture begins after the 8.2 kiloyear event which was a sudden decrease in global temperatures starting ca. 6200 BC and which lasted for about two to four centuries. In around ca. 6000–4200 B.C the Shulaveri-Shomu and other Neolithic/Chalcolithic cultures of the Southern Caucasus use local obsidian for tools, raise animals such as cattle and pigs, and grow crops, including grapes.

Many of the characteristic traits of the Shulaverian material culture (circular mudbrick architecture, pottery decorated by plastic design, anthropomorphic female figurines, obsidian industry with an emphasis on production of long prismatic blades) are believed to have their origin in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Hassuna, Halaf).

Shulaveri culture predates the Kura-Araxes culture and surrounding areas, which is assigned to the period of ca. 4000 – 2200 BC, and had close relation with the middle Bronze Age culture called Trialeti culture (ca. 3000 – 1500 BC). Sioni culture of Eastern Georgia possibly represents a transition from the Shulaveri to the Kura-Arax cultural complex.

The Halaf culture is a prehistoric period which lasted between about 6100 and 5500 BCE. The period is a continuous development out of the earlier Pottery Neolithic and is located primarily in south-eastern Turkey, Syria, and northern Iraq, although Halaf-influenced material is found throughout Greater Mesopotamia.

Halaf pottery has been found in other parts of northern Mesopotamia, such as at Nineveh and Tepe Gawra, Chagar Bazar and at many sites in Anatolia (Turkey) suggesting that it was widely used in the region. In addition, the Halaf communities made female figurines of partially baked clay and stone and stamp seals of stone.

The seals are thought to mark the development of concepts of personal property, as similar seals were used for this purpose in later times. The Halaf people used tools made of stone and clay. Copper was also known, but was not used for tools.

The Halaf period was succeeded by the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period (~5500 – 5200 cal. BCE) and then by the Ubaid period (~5200 – 4000 cal. BCE). It is a very poorly understood period and was created to explain the gradual change from Halaf style pottery to Ubaid style pottery in North Mesopotamia.

The Ubaid period (ca. 6500 to 3800 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-Ubaid, a low, relatively small tell (settlement mound) west of nearby Ur in southern Iraq’s Dhi Qar Governorate, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvium although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.

In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

The Leyla-Tepe culture includes a settlement in the lower layer of the settlements Poilu I, Poilu II, Boyuk-Kesik I and Boyuk-Kesik II. They apparently buried their dead in ceramic vessels. Similar amphora burials in the South Caucasus are found in the Western Georgian Jar-Burial Culture, anarchaeological culture that was widespread in the second century B.C. to the eighth century A.D. in the basins of the Kura and Araks rivers in Transcaucasia, particularly in Caucasian Albania.

The culture has also been linked to the north Ubaid period monuments, in particular, with the settlements in the Eastern Anatolia Region (Arslan-tepe, Coruchu-tepe, Tepechik, etc.). The settlement is of a typical Western-Asian variety, with the dwellings packed closely together and made of mud bricks with smoke outlets.

It has been suggested that the Leyla-Tepe were the founders of the Maykop culture. An expedition to Syria by the Russian Academy of Sciences revealed the similarity of the Maykop and Leyla-Tepe artifacts with those found recently while excavating the ancient city of Tel Khazneh I, from the 4th millennium BC.

The name of the culture is derived from the Kura and Araxes river valleys. Its territory corresponds to parts of modern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Dagestan, Georgia, Ingushetia and North Ossetia. It may have given rise to the later Khirbet Kerak ware culture found in Syria and Canaan after the fall of the Akkadian Empire.

At some point the culture’s settlements and burial grounds expanded out of lowland river valleys and into highland areas. Although some scholars have suggested that this expansion demonstrates a switch from agriculture to pastoralism, and that it serves as possible proof of a large-scale arrival of Indo-Europeans, facts such as that settlement in the lowlands remained more or less continuous suggest merely that the people of this culture were diversifying their economy to encompass both crop and livestock agriculture.

The economy was based on farming and livestock-raising (especially of cattle and sheep). They grew grain and various orchard crops, and are known to have used implements to make flour. They raised cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and in its later phases, horses (introduced around 3000 BCE, probably by Indo-European speaking tribes from the North).

There is evidence of trade with Mesopotamia, as well as Asia Minor. It is, however, considered above all to be indigenous to the Caucasus, and its major variants characterized (according to Caucasus historian Amjad Jaimoukha) later major cultures in the region.

In its earliest phase, metal was scant, but it would later display “a precocious metallurgical development which strongly influenced surrounding regions”. They worked copper, arsenic, silver, gold, tin, and bronze. Their metal goods were widely distributed, recorded in the Volga, Dnieper and Don-Donets systems in the north, into Syria and Palestine in the south, and west into Anatolia.

Their pottery was distinctive; in fact, the spread of their pottery along trade routes into surrounding cultures was much more impressive than any of their achievements domestically. It was painted black and red, using geometric designs for ornamentation. Examples have been found as far south as Syria and Israel, and as far north as Dagestan and Chechnya.

The spread of this pottery, along with archaeological evidence of invasions, suggests that the Kura-Araxes people may have spread outward from their original homes, and most certainly, had extensive trade contacts. Jaimoukha believes that its southern expanse is attributable primarily to Mitanni and the Hurrians.

The culture is closely linked to the approximately contemporaneous Maykop culture of Transcaucasia. As Amjad Jaimoukha puts it: “The Kura-Araxes culture was contiguous, and had mutual influences, with the Maikop culture in the Northwest Caucasus. According to E.I.Krupnov (1969:77), there were elements of the Maikop culture in the early memorials of Chechnya and Ingushetia in the Meken and Bamut kurgans and in Lugovoe in Serzhen-Yurt.

Similarities between some features and objects of the Maikop and Kura-Araxes cultures, such as large square graves, the bold-relief curvilinear ornamentation of pottery, ochre-coloured ceramics, earthen hearth props with horn projections, flint arrowheads, stone axes and copper pitchforks are indicative of a cultural unity that pervaded the Caucasus in the Neolithic Age.”

Inhumation practices are mixed. Flat graves are found, but so are substantial kurgan burials, the latter of which may be surrounded by cromlechs. This points to a heterogeneous ethno-linguistic population.

They are also remarkable for the production of wheeled vehicles (wagons and carts), which were sometimes included in burial kurgans. Late in the history of this culture, its people built kurgans of greatly varying sizes, containing greatly varying amounts and types of metalwork, with larger, wealthier kurgans surrounded by smaller kurgans containing less wealth.

This trend suggests the eventual emergence of a marked social hierarchy. Their practice of storing relatively great wealth in burial kurgans was probably a cultural influence from the more ancient civilizations of the Fertile Crescent to the south.

The Trialeti culture, named after Trialeti region of Georgia, is attributed to the first part of the 2nd millennium BC. In the late 3rd millennium BC, settlements of the Kura-Araxes culture began to be replaced by early Trialeti culture sites.

The Trialeti culture was a second culture to appear in Georgia, after the Shulaveri-Shomu culture which existed from 6000 to 4000 BC. The Trialeti culture shows close ties with the highly developed cultures of the ancient world, particularly with the Aegean, but also with cultures to the south, such as probably the Sumerians and their Akkadian conquerors.

The site at Trialeti was originally excavated in 1936–1940 in advance of a hydroelectric scheme, when forty-six barrows were uncovered. A further six barrows were uncovered in 1959–1962.

The Trialeti culture was known for its particular form of burial. The elite were interred in large, very rich burials under earth and stone mounds, which sometimes contained four-wheeled carts. Also there were many gold objects found in the graves. These gold objects were similar to those found in Iran and Iraq.

They also worked tin and arsenic. This form of burial in a tumulus or “kurgan”, along with wheeled vehicles, is the same as that of the Kurgan culture which has been associated with the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. In fact, the black burnished pottery of especially early Trialeti kurgans is similar to Kura-Araxes pottery.

In a historical context, their impressive accumulation of wealth in burial kurgans, like that of other associated and nearby cultures with similar burial practices, is particularly noteworthy. This practice was probably a result of influence from the older civilizations to the south in the Fertile Crescent.

Hayasa-Azzi or Azzi-Hayasa was a Late Bronze Age confederation formed between two kingdoms of Armenian Highlands, Hayasa located South of Trabzon and Azzi, located north of the Euphrates and to the south of Hayasa. The Hayasa-Azzi confederation was in conflict with the Hittite Empire in the 14th century BC, leading up to the collapse of Hatti around 1190 BC.

Nairi was the Assyrian name (KUR.KUR Na-i-ri, also Na-‘i-ru) for a Proto-Armenian (Hurrian-speaking) tribe in the Armenian Highlands, roughly corresponding to the modern Van and Hakkâri provinces of modern Turkey.

The word is also used to describe the tribes who lived there, whose ethnic identity is uncertain. Nairi has sometimes been equated with Nihriya, known from Mesopotamian, Hittite, and Urartean sources. However, its co-occurrence with Nihriya within a single text may argue against this.

During the Bronze Age collapse (13th to 12th centuries BC), the Nairi tribes were considered a force strong enough to contend with both Assyria and Hatti. The Battle of Nihriya, the culminating point of the hostilities between Hittites and Assyrians for control over the remnants of the former empire of Mitanni, took place there, circa 1230. Nairi was incorporated into Urartu during the 10th century BC.

Urartu, corresponding to the biblical Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili;) was an Iron Age kingdom centred around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands.

Strictly speaking, Urartu is the Assyrian term for a geographical region, while “kingdom of Urartu” or “Biainili lands” are terms used in modern historiography for the Proto-Armenian (Hurro-Urartian) speaking Iron Age state that arose in that region. That a distinction should be made between the geographical and the political entity was already pointed out by König (1955).

The landscape corresponds to the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highlands. The kingdom rose to power in the mid-9th century BC, but was conquered by Media in the early 6th century BC. The heirs of Urartu are the Armenians and their successive kingdoms.

The main object of early Assyrian incursions into Armenia was to obtain metals. The iron-working age followed that of bronze everywhere, opening a new epoch of human progress. Its influence is noticeable in Armenia, and the transition period is well marked. Tombs whose metal contents are all of bronze are of an older epoch. In most of the cemeteries explored, both bronze and iron furniture were found, indicating the gradual advance into the Iron Age.

It is generally proposed that a proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age when the latter, around 1500 BC, mixed with indigenous peoples. We speak of proto-Thracians from which during the Iron Age (about 1000 BC) Dacians and Thracians begin developing.

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the 5th century BC. Like the Illyrians, the mountainous regions were home to people regarded as various warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable.

Thracians inhabited parts of the ancient provinces: Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia, Mysia, Pannonia, and other regions on the Balkans and Anatolia. This area extends over most of the Balkans region, and the Getae north of the Danube as far as beyond the Bug and including Panonia in East.

The beginning

The term “Natufian” was coined by Dorothy Garrod who studied the Shuqba cave in Wadi an-Natuf, in the western Judean Mountains, about halfway between Tel Aviv and Ramallah.

The Natufian culture was an Epipaleolithic culture that existed from 13,000 to 9,800 B.C. in the Levant, a region in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was unusual in that it was sedentary, or semi-sedentary, before the introduction of agriculture.

The Natufian communities are possibly the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. There is some evidence for the deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture, at the Tell Abu Hureyra site, the site for earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. Generally, though, Natufians made use of wild cereals. Animals hunted included gazelles.

The period is commonly split into two subperiods: Early Natufian (12,500–10,800 BC) and Late Natufian (10,800–9500 BC). The Late Natufian most likely occurred in tandem with the Younger Dryas (10,800 to 9500 BC). In the Levant, there are more than a hundred kinds of cereals, fruits, nuts and other edible parts of plants, and the flora of the Levant during the Natufian period was not the dry, barren, and thorny landscape of today, but woodland.

The Natufian developed in the same region as the earlier Kebaran complex, and is generally seen as a successor which developed from at least elements within that earlier culture. There were also other cultures in the region, such as the Mushabian culture of the Negev and Sinai, which are sometimes distinguished from the Kebaran, and sometimes also seen as having played a role in the development of the Natufian.

More generally there has been discussion of the similarities of these cultures with those found in coastal North Africa. Graeme Barker notes there are: “similarities in the respective archaeological records of the Natufian culture of the Levant and of contemporary foragers in coastal North Africa across the late Pleistocene and early Holocene boundary”.

Ofer Bar-Yosef has argued that there are signs of influences coming from North Africa to the Levant, citing the microburin technique and “microlithic forms such as arched backed bladelets and La Mouillah points.”

But recent research has shown that the presence of arched backed bladelets, La Mouillah points, and the use of the microburin technique was already apparent in the Nebekian industry of the Eastern Levant and Maher et al. state that, “Many technological nuances that have often been always highlighted as significant during the Natufian were already present during the Early and Middle EP [Epipalaeolithic] and do not, in most cases, represent a radical departure in knowledge, tradition, or behavior.”

Authors such as Christopher Ehret have built upon the little evidence available to develop scenarios of intensive usage of plants having built up first in North Africa, as a precursor to the development of true farming in the Fertile Crescent, but such suggestions are considered highly speculative until more North African archaeological evidence can be gathered. In fact, Weiss et al. have shown that the earliest known intensive usage of plants was in the Levant 23,000 years ago at the Ohalo II site.

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace in a recent study on cranial metric traits however, was also able to identify a “clear link” to Sub-Saharan African populations for early Natufians based on his observation of gross anatomical similarity with extant populations found mostly in the Sahara. Brace believes that these populations later became assimilated into the broader continuum of Southwest Asian populations.

According to Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen, “It seems that certain preadaptive traits, developed already by the Kebaran and Geometric Kebaran populations within the Mediterranean park forest, played an important role in the emergence of the new socioeconomic system known as the Natufian culture.”

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was not in use yet. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating around 8000 to 7000 BC. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.

PPNA archaeological sites are much larger than those of the preceding Natufian hunter-gatherer culture, and contain traces of communal structures, such as the famous tower of Jericho. One of the most notable PPNA settlements is Jericho, thought to be the world’s first town (c 8000 BC). The PPNA town contained a population of up to 2,000-3,000 people, and was protected by a massive stone wall and tower.

Sedentism of this time allowed for the cultivation of local grains, such as barley and wild oats, and for storage in granaries. Sites such as Dhra′ and Jericho retained a hunting lifestyle until the PPNB period, but granaries allowed for year-round occupation. This period of cultivation is considered “pre-domestication”, but may have begun to develop plant species into the domesticated forms they are today.

Deliberate, extended-period storage was made possible by the use of “suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents”. This practice “precedes the emergence of domestication and large-scale sedentary communities by at least 1,000 years”.

Granaries are positioned in places between other buildings early on 9500 BC. However beginning around 8500 BC, they were moved inside houses, and by 7500 BC storage occurred in special rooms. This change might reflect changing systems of ownership and property as granaries shifted from a communal use and ownership to become under the control of households or individuals.

It has been observed of these granaries that their “sophisticated storage systems with subfloor ventilation are a precocious development that precedes the emergence of almost all of the other elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic package—domestication, large scale sedentary communities, and the entrenchment of some degree of social differentiation”. Moreover, “Building granaries may … have been the most important feature in increasing sedentism that required active community participation in new life-ways”.

PPNA cultures are unique for their burial practices, and Kenyon (who excavated the PPNA level of Jericho), characterized them as “living with their dead”. Kenyon found no fewer than 279 burials, below floors, under household foundations, and in between walls. In the PPNB period, skulls were often dug up and reburied, or mottled with clay and (presumably) displayed.

The lithic industry is based on blades struck from regular cores. Sickle-blades and arrowheads continue traditions from the late Natufian culture, transverse-blow axes and polished adzes appear for the first time.

With more sites becoming known, archaeologists have defined a number of regional variants:

- ‘Sultanian’ in the Jordan River valley and southern Levant with the type site of Jericho. Other sites include Netiv HaGdud, El-Khiam, Hatoula and Nahal Oren.

- ‘Mureybetian’ in the Northern Levant. Defined by the finds from Mureybet IIIA, IIIB, typical: Helwan points, sickle-blades with base amenagée or short stem and terminal retouch. Other sites include Sheyk Hasan and Jerf el-Ahmar.

- ‘Aswadian’ in the Damascus Basin. Defined by finds from Tell Aswad IA. Typical: bipolar cores, big sickle blades, Aswad points. The ‘Aswadian’ variant was recently abolished by the work of Danielle Stordeur in her initial report from further investigations in 2001–2006. The PPNB horizon was moved back at this site, to around 8700 BC.

- sites in ‘Upper Mesopotamia’ include Çayönü and Göbekli Tepe, with the latter possibly being the oldest religious structural complex yet discovered.

- sites in central Anatolia which include the ‘mother city’ Çatal höyük and the smaller but older site, rivaling even Jericho in age, Aşıklı Höyük.

Göbekli Tepe (“Potbelly Hill”) is an archaeological site at the top of a mountain ridge in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, approximately 6 km (4 mi) northeast of the town of Şanlıurfa. The tell has a height of 15 m (49 ft) and is about 300 m (984 ft) in diameter.

The tell includes two phases of ritual use dating back to the 10th-8th millennium BCE. During the first phase (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected. In the second phase (Pre-pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. The site was abandoned after the PPNB-period. Younger structures date to classical times.

The imposing stratigraphy of Göbekli Tepe attests to many centuries of activity, beginning at least as early as the epipaleolithic period. Structures identified with the succeeding period, PPNA, have been dated to the 10th millennium BCE. Remains of smaller buildings identified as PPNB and dating from the 9th millennium BCE have also been unearthed.

The inhabitants are assumed to have been hunters and gatherers who nevertheless lived in villages for at least part of the year. So far, very little evidence for residential use has been found. Through the radiocarbon method, the end of Layer III can be fixed at about 9000 BCE (see above) but it is believed that the elevated location may have functioned as a spiritual center by 11,000 BCE or even earlier.

The surviving structures, then, not only predate pottery, metallurgy, and the invention of writing or the wheel, they were built before the so-called Neolithic Revolution, i.e., the beginning of agriculture and animal husbandry around 9000 BCE. But the construction of Göbekli Tepe implies organization of an advanced order not hitherto associated with Paleolithic, PPNA, or PPNB societies.

Schmidt’s view, shared by most experts, was that Göbekli Tepe is a stone-age mountain sanctuary. Radiocarbon dating as well as comparative, stylistic analysis indicates that it is the oldest religious site yet discovered anywhere. Schmidt believed that what he called this “cathedral on a hill” was a pilgrimage destination attracting worshippers up to 100 miles (160 km) distant.

Butchered bones found in large numbers from local game such as deer, gazelle, pigs, and geese have been identified as refuse from food hunted and cooked or otherwise prepared for the congregants.

Schmidt considered Göbekli Tepe a central location for a cult of the dead and that the carved animals are there to protect the dead. Though no tombs or graves have been found so far, Schmidt believed that they remain to be discovered in niches located behind the sacred circles’ walls. Schmidt also interpreted it in connection with the initial stages of the Neolithic.

It is one of several sites in the vicinity of Karaca Dağ, an area which geneticists suspect may have been the original source of at least some of our cultivated grains. Recent DNA analysis of modern domesticated wheat compared with wild wheat has shown that its DNA is closest in sequence to wild wheat found on Mount Karaca Dağ 20 miles (32 km) away from the site, suggesting that this is where modern wheat was first domesticated. Such scholars suggest that the Neolithic revolution, i.e., the beginnings of grain cultivation, took place here.

Schmidt believed, as others do, that mobile groups in the area were compelled to cooperate with each other to protect early concentrations of wild cereals from wild animals (herds of gazelles and wild donkeys). Wild cereals may have been used for sustenance more intensively than before and were perhaps deliberately cultivated.

This would have led to early social organization of various groups in the area of Göbekli Tepe. Thus, according to Schmidt, the Neolithic did not begin on a small scale in the form of individual instances of garden cultivation, but developed rapidly in the form of “a large-scale social organization”

Schmidt engaged in some speculation regarding the belief systems of the groups that created Göbekli Tepe, based on comparisons with other shrines and settlements. He assumed shamanic practices and suggested that the T-shaped pillars represent human forms, perhaps ancestors, whereas he saw a fully articulated belief in gods only developing later in Mesopotamia, associated with extensive temples and palaces.

This corresponds well with an ancient Sumerian belief that agriculture, animal husbandry, and weaving were brought to mankind from the sacred mountain Ekur, which was inhabited by Annuna deities, very ancient gods without individual names. Schmidt identified this story as a primeval oriental myth that preserves a partial memory of the emerging Neolithic.

It is also apparent that the animal and other images give no indication of organized violence, i.e. there are no depictions of hunting raids or wounded animals, and the pillar carvings ignore game on which the society mainly subsisted, like deer, in favor of formidable creatures like lions, snakes, spiders, and scorpions.

Göbekli Tepe is regarded as an archaeological discovery of the greatest importance since it could profoundly change the understanding of a crucial stage in the development of human society. Ian Hodder of Stanford University said, “Göbekli Tepe changes everything”. It shows that the erection of monumental complexes was within the capacities of hunter-gatherers and not only of sedentary farming communities as had been previously assumed. As excavator Klaus Schmidt put it, “First came the temple, then the city.”

Not only its large dimensions, but the side-by-side existence of multiple pillar shrines makes the location unique. There are no comparable monumental complexes from its time. Nevalı Çori, a Neolithic settlement also excavated by the German Archaeological Institute and submerged by the Atatürk Dam since 1992, is 500 years later. Its T-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its shrine was located inside a village. The roughly contemporary architecture at Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture, and Çatal höyük, perhaps the most famous Anatolian Neolithic village, is also 2,000 years later.

At present Göbekli Tepe raises more questions for archaeology and prehistory than it answers. It remains unknown how a force large enough to construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was mobilized and compensated or fed in the conditions of pre-sedentary society. Scholars cannot interpret the pictograms, and do not know for certain what meaning the animal reliefs had for visitors to the site.

The variety of fauna depicted, from lions and boars to birds and insects, makes any single explanation problematic. As there is little or no evidence of habitation, and the animals pictured are mainly predators, the stones may have been intended to stave off evils through some form of magic representation. Alternatively, they could have served as totems.

The assumption that the site was strictly cultic in purpose and not inhabited has also been challenged by the suggestion that the structures served as large communal houses, “similar in some ways to the large plank houses of the Northwest Coast of North America with their impressive house posts and totem poles.” It is not known why every few decades the existing pillars were buried to be replaced by new stones as part of a smaller, concentric ring inside the older one. Human burial may or may not have occurred at the site.

Around the beginning of the 8th millennium BCE Göbekli Tepe (“Potbelly Hill”) lost its importance. The advent of agriculture and animal husbandry brought new realities to human life in the area, and the “Stone-age zoo” (Schmidt’s phrase applied particularly to Layer III, Enclosure D) apparently lost whatever significance it had had for the region’s older, foraging communities.

But the complex was not simply abandoned and forgotten to be gradually destroyed by the elements. Instead, each enclosure was deliberately buried under as much as 300 to 500 cubic meters (390 to 650 cu yd) of refuse consisting mainly of small limestone fragments, stone vessels, and stone tools. Many animal, even human, bones have also been identified in the fill. Why the enclosures were buried is unknown, but it preserved them for posterity.

The reason the complex was carefully backfilled remains unexplained. Until more evidence is gathered, it is difficult to deduce anything certain about the originating culture or the site’s significance.

Haplogroup G descends from macro-haplogroup F, which is thought to represent the second major migration of Homo sapiens out of Africa, at least 60,000 years ago. While the earlier migration of haplogroups C and D had followed the coasts of South Asia as far as Oceania and the Far East, haplogroup F penetrated through the Arabian peninsula and settled in the Middle East.

Its main branch, macro-haplogroup IJK would become the ancestor of 80% of modern Eurasian people. Haplogroup G had a slow start, evolving in apparent isolation for tens of thousands of years, possibly in Southwest Asia, cut off from the wave of colonisation of Eurasia.

Members of haplogroup G2 appear to have been closely linked to the development of early agriculture in the Levant part of the Fertile Crescent, starting 11,500 years before present. The G2a branch expanded to Anatolia, the Caucasus and Europe, while G2b ended up secluded in the southern Levant and is now found mostly among Jewish people.

It has now been proven by the testing of Neolithic remains in various parts of Europe that haplogroup G2a was one of the lineages of Neolithic farmers and herders who migrated from Anatolia to Europe between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago. In this scenario migrants from the eastern Mediterranean would have brought with them sheep and goats, which were domesticated south of the Caucasus about 12,000 years ago. This would explain why haplogroup G is more common in mountainous areas, be it in Europe or in Asia.

The geographic continuity of G2a from Anatolia to Thessaly to the Italian peninsula, Sardinia, south-central France and Iberia already suggested that G2a could be connected to the Printed-Cardium Pottery culture (5000-1500 BCE).

There has so far been ancient Y-DNA analysis from only four Neolithic cultures (LBK in Germany, Remedello in Italy and Cardium Pottery in south-west France and Spain), and all sites yielded G2a individuals, which is the strongest evidence at present that farming originated with and was disseminated by members of haplogroup G (although probably in collaboration with other haplogroups such as E1b1b, J, R1b and T).

The highest genetic diversity within haplogroup G is found between the Levant and the Caucasus, in the Fertile Crescent, which is a good indicator of its region of origin. It is thought that early Neolithic farmers expanded from the Levant and Mesopotamia westwards to Anatolia and Europe, eastwards to South Asia, and southwards to the Arabian peninsula and North and East Africa.

The domestication of goats and cows first took place in the mountainous region of eastern Anatolia, including the Caucasus and Zagros. This is probably where the roots of haplogroup G2a (and perhaps of all haplogroup G) are to be found. So far, the only G2a people negative for subclades downstream of P15 or L149.1 were found exclusively in the South Caucasus region.

Haplogroup G has an overall low frequency in most populations but is widely distributed within ethnic groups of the Old World in the Middle East, Europe, Caucasus, South Asia, western and central Asia, and northern Africa.

Haplogroup G2a (SNP P15+) has been identified in neolithic human remains in Europe dating between 5000-3000BC. Furthermore, the majority of all the male skeletons from the European Neolithic period have so far yielded Y-DNA belonging to this haplogroup.

The oldest skeletons confirmed by ancient DNA testing as carrying haplogroup G2a were five found in the Avellaner cave burial site for farmers in northeastern Spain and were dated by radiocarbon dating to about 7000 years ago.

At the Neolithic cemetery of Derenburg Meerenstieg II, north central Germany, with burial artifacts belonging to the Linear Pottery culture, known in German as Linearbandkeramik (LBK). This skeleton could not be dated by radiocarbon dating, but other skeletons there were dated to between 5,100 and 6,100 years old.

The most detailed SNP mutation identified was S126 (L30), which defines G2a3. G2a was found also in 20 out of 22 samples of ancient Y-DNA from Treilles, the type-site of a Late Neolithic group of farmers in the South of France, dated to about 5000 years ago.

The fourth site also from the same period is the Ötztal of the Italian Alps where the mummified remains of Ötzi the Iceman were discovered. Preliminary word is that the Iceman belongs to haplogroup G2a2b (earlier called G2a4).

Haplogroup J2 is thought to have appeared somewhere in the Middle East towards the end of the last glaciation, between 15,000 and 22,000 years ago. Its present geographic distribution argues in favor of a Neolithic expansion from the Fertile Crescent.

This expansion probably correlated with the diffusion of domesticated of cattle and goats (starting c. 8000-9000 BCE) from the Zagros mountains and northern Mesopotamia, rather than with the development of cereal agriculture in the Levant (which appears to be linked rather to haplogroups G2 and E1b1b).

A second expansion of J2 could have occured with the advent of metallurgy, notably copper working (from the Lower Danube valley, central Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia), and the rise of some of the oldest civilisations.

Quite a few ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilisations flourished in territories where J2 lineages were preponderant. This is the case of the Hattians, the Hurrians, the Etruscans, the Minoans, the Greeks, the Phoenicians (and their Carthaginian offshoot), the Israelites, and to a lower extent also the Romans, the Assyrians and the Persians. All the great seafaring civilisations from the middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age were dominated by J2 men.

There is a distinct association of ancient J2 civilisations with bull worship. The oldest evidence of a cult of the bull can be traced back to Neolithic central Anatolia, notably at the sites of Çatal höyük and Alaca Höyük.

Bull depictions are omnipresent in Minoan frescos and ceramics in Crete. Bull-masked terracotta figurines and bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus (dating back as far as the Neolithic, the first presumed expansion of J2 from West Asia). The Hattians, Sumerians, Babylonians, Canaaites, and Carthaginians all had bull deities (in contrast with Indo-European or East Asian religions).

The sacred bull of Hinduism, Nandi, present in all temples dedicated to Shiva or Parvati, does not have an Indo-European origin, but can be traced back to Indus Valley civilisation. Minoan Crete, Hittite Anatolia, the Levant, Bactria and the Indus Valley also shared a tradition of bull leaping, the ritual of dodging the charge of a bull. It survives today in the traditional bullfighting of Andalusia in Spain and Provence in France, two regions with a high percentage of J2 lineages.