General characteristics of Indo-European religion

Counter-Intelligence: Shining a light on Black Operations

Counter-Intelligence: Shining a light on Black Operations

An extraordinary work by a gifted filmmaker, “Counter-Intelligence” shines sunlight into the darkest crevices of empire run amok. The film vividly exposes a monstrous and unconstitutional “deep state” in which multiple competing chains of command — all but one illegal — hijack government capabilities and taxpayer funds to commit crimes against humanity in our name. Anyone who cares about democracy, good government, and the future will want to watch all five segments of this remarkable film.

– Robert David STEELE Vivas: CIA, USMC, OSS, Earth Intelligence Network and Founder

Filed under: Uncategorized

The thunder god

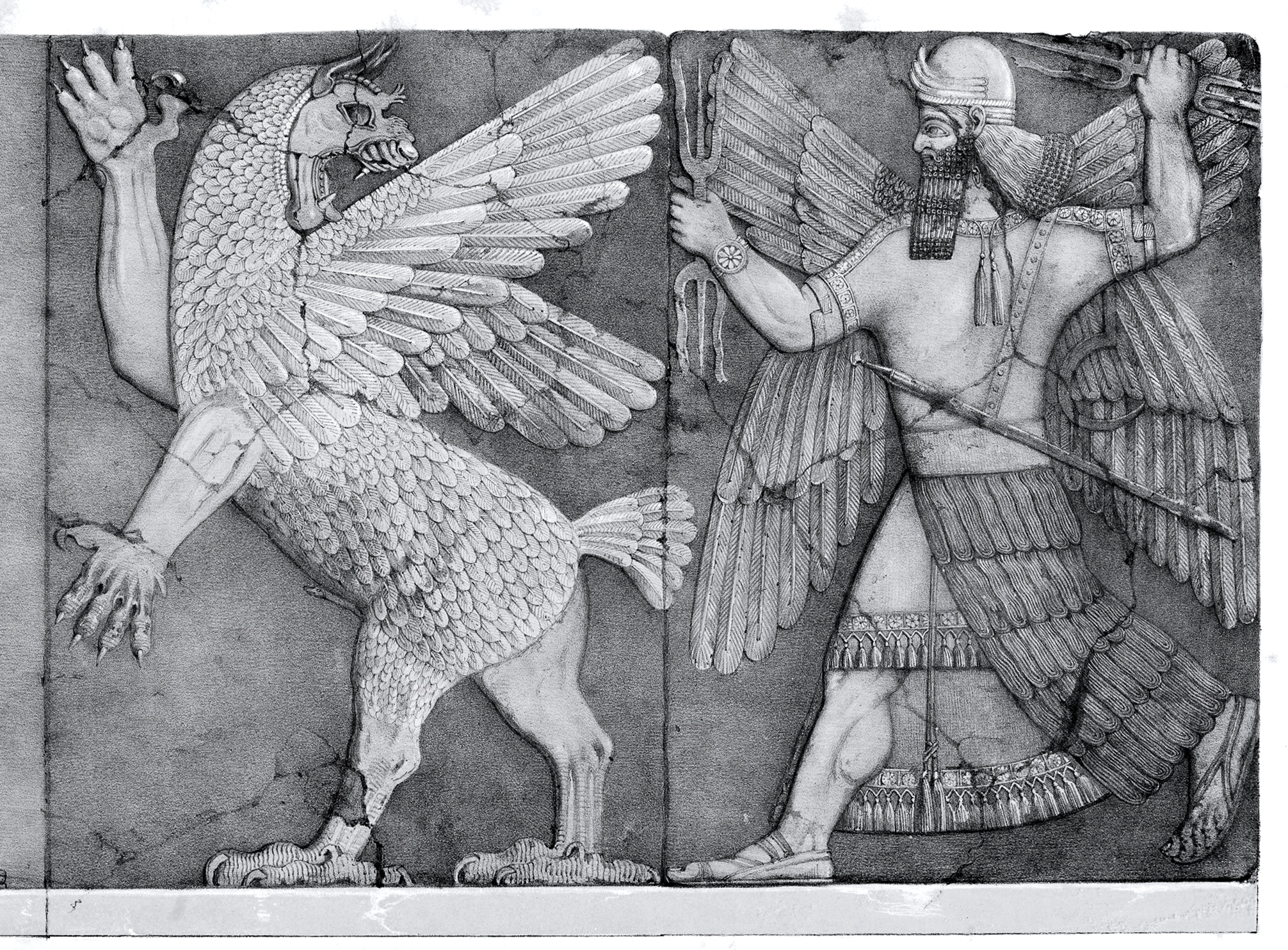

Enlil, wind god, with his thunderbolts pursues Anzu after Anzu stole the Tablets of Destiny (from Austen Henry Layard Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853)

Anzû (before misread as Zû), also known as Imdugud (meaning heavy rain, slingstone, ball of clay, thunderbird, hail storm), in Sumerian, (from An “heaven” and Zu “to know”, in the Sumerian language) is a lesser divinity or monster of Akkadian mythology, and the son of the bird goddess Siris, the patron of beer who is conceived of as a demon, which is not necessarily evil. Siris is considered the mother of Zu. Siris and Zu are large birds that can breathe fire and water.

Im-gíri means lightning storm (‘storm’ + ‘lightning flash’), im…mir means to be windy (‘wind’ + ‘storm wind’), im-ri-ha-mun means storm, whirlwind (‘weather’ + ‘to blow’ + ‘mutually opposing’), im…šèg means to rain (‘storm’ + ‘to rain’), and im-u-lu means southwind (‘wind’ + ‘storm’).

In Sumerian Tu, and damu, means weak, young or child. The Sumerian word /tur/ is also an allusion to the word for uterus/womb (šà-tùr). Some scholars follow the traditional interpretation that the element /tu/ is the same as the Sumerian verb /tudr/ “to give birth,” but this has been contested on phonological grounds.

Gugalanna

Gu or gud means ox, bull. In Mesopotamian mythology, Gugalanna (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”) was a Sumerian deity as well as the constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies.

Gugalanna was the first husband of the Goddess Ereshkigal, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, a gloomy place devoid of light. It was to share the sorrow with her sister that Inanna later descends to the Underworld.

Taurus was a constellation of the Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox from about 3,200 BCE. It marked the start of the agricultural year with the New Year Akitu festival (from á-ki-ti-še-gur-ku, = sowing of the barley), an important date in Mespotamian religion.

The death of Gugalanna, represents the obscuring disappearance of this constellation as a result of the light of the sun, with whom Gilgamesh was identified.

In the time in which this myth was composed, the Akitu festival at the Spring Equinox, due to the Precession of the Equinoxes did not occur in Aries, but in Taurus. At this time of the year, Taurus would have disappeared as it was obscured by the sun.

Joseph Campbell wrote in The masks of God: Oriental mythology (1991): “Between the period of the earliest female figurines circa 4500 B.C. … a span of a thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilised by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth.

Moreover by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and the laws of sky and earth.”

Enlil

Enlil (nlin) (EN = Lord + LÍL = Wind, “Lord (of the) Storm”) is the God of breath, wind, loft and breadth (height and distance). It was the name of a chief deity listed and written about in Sumerian religion, and later in Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian), Hittite, Canaanite and other Mesopotamian clay and stone tablets.

The name is perhaps pronounced and sometimes rendered in translations as “Ellil” in later Akkadian, Hittite, and Canaanite literature. In later Akkadian, Enlil is the son of Anshar and Kishar. Enlil was known as the inventor of the mattock (a key agricultural pick, hoe, ax or digging tool of the Sumerians) and helped plants to grow.

The myth of Enlil and Ninlil discusses when Enlil was a young god, he was banished from Ekur in Nippur, home of the gods, to Kur, the underworld for seducing a goddess named Ninlil. Ninlil followed him to the underworld where she bore his first child, the moon god Sin (Sumerian Nanna/Suen). After fathering three more underworld-deities (substitutes for Sin), Enlil was allowed to return to the Ekur.

By his wife Ninlil or Sud, Enlil was father of the moon god Nanna/Suen (in Akkadian, Sin) and of Ninurta (also called Ningirsu). Enlil is the father of Nisaba the goddess of grain, of Pabilsag who is sometimes equated with Ninurta, and sometimes of Enbilulu. By Ereshkigal Enlil was father of Namtar.

In one myth, Enlil gives advice to his son, the god Ninurta, advising him on a strategy to slay the demon Asag. This advice is relayed to Ninurta by way of Sharur, his enchanted talking mace, which had been sent by Ninurta to the realm of the gods to seek counsel from Enlil directly.

Enlil is associated with the ancient city of Nippur, sometimes referred to as the cult city of Enlil. His temple was named Ekur, “House of the Mountain.” Such was the sanctity acquired by this edifice that Babylonian and Assyrian rulers, down to the latest days, vied with one another to embellish and restore Enlil’s seat of worship. Eventually, the name Ekur became the designation of a temple in general.

Grouped around the main sanctuary, there arose temples and chapels to the gods and goddesses who formed his court, so that Ekur became the name for an entire sacred precinct in the city of Nippur. The name “mountain house” suggests a lofty structure and was perhaps the designation originally of the staged tower at Nippur, built in imitation of a mountain, with the sacred shrine of the god on the top.

Enlil was also known as the god of weather. According to the Sumerians, Enlil helped create the humans, but then got tired of their noise and tried to kill them by sending a flood. A mortal known as Utnapishtim survived the flood through the help of another god, Ea, and he was made immortal by Enlil after Enlil’s initial fury had subsided.

As Enlil was the only god who could reach An, the god of heaven, he held sway over the other gods who were assigned tasks by his agent and would travel to Nippur to draw in his power. He is thus seen as the model for kingship. Enlil was assimilated to the north “Pole of the Ecliptic”. His sacred number name was 50.

At a very early period prior to 3000 BC, Nippur had become the centre of a political district of considerable extent. Inscriptions found at Nippur, where extensive excavations were carried on during 1888–1900 by John P. Peters and John Henry Haynes, under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, show that Enlil was the head of an extensive pantheon. Among the titles accorded to him are “king of lands”, “king of heaven and earth”, and “father of the gods”.

Enki (Capricorn)

Capricorn is the tenth astrological sign in the zodiac, originating from the constellation of Capricornus. It spans the 270–300th degree of the zodiac, corresponding to celestial longitude. Capricorn is ruled by the planet Saturn. In astrology, Capricorn is considered an earth sign, introvert sign, and one of the four cardinal signs.

Under the tropical zodiac, the sun transits this area from December 22 to January 19 each year, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun currently transits the constellation of Capricorn from approximately January 15 to February 14.

The Encyclopedia Britannica states that the figure of Capricorn derives from the half-goat, half-fish representation of the Sumerian god Enki.

Enki (EN.KI(G)), later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology, was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation (Nudimmud: nu, likeness, dim mud, make beer).

The main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu. He was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization.

His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, sometimes confused with the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water'”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He was accompanied by an attendant Isimud, who is readily identifiable by the fact that he possesses two faces looking in opposite directions.

He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki.

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael), with Ia.

Jean Bottero (1952) and others suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea, Enki’s Akkadian name, associating the Canaanite theonym Yahu, and ultimately Hebrew YHWH.

This hypothesis is dismissed by some scholars as erroneous, based on a mistaken cuneiform reading, but academic debate continues. Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic Yamm (sea), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw, or Ya’a.

Saturn (Capricorn)

Saturn (Latin: Saturnus) is a god in ancient Roman religion, and a character in myth. Saturn is a complex figure because of his multiple associations and long history. He was the first god of the Capitol, known since the most ancient times as Saturnius Mons, and was seen as a god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation.

In later developments he came to be also a god of time. His reign was depicted as a Golden Age of plenty and peace. Macrobius states explicitly that the Roman legend of Janus and Saturn is an affabulation, as the true meaning of religious beliefs cannot be openly expressed.

In the myth Saturn was the original and autochthonous ruler of the Capitolium, which had thus been called the Mons Saturnius in older times and on which once stood the town of Saturnia. He was sometimes regarded as the first king of Latium or even the whole of Italy.

At the same time, there was a tradition that Saturn had been an immigrant god, received by Janus after he was usurped by his son Jupiter and expelled from Greece. In Versnel’s view his contradictions – a foreigner with one of Rome’s oldest sanctuaries, and a god of liberation who is kept in fetters most of the year – indicate Saturn’s capacity for obliterating social distinctions.

The Golden Age of Saturn’s reign in Roman mythology differed from the Greek tradition. He arrived in Italy “dethroned and fugitive,” but brought agriculture and civilization for which things was rewarded by Janus with a share of the kingdom, becoming he himself king.

Saturn is associated with a major religious festival in the Roman calendar, Saturnalia. Saturnalia celebrated the harvest and sowing, and ran from December 17–23. Macrobius (5th century AD) presents an interpretation of the Saturnalia as a festival of light leading to the winter solstice.

The renewal of light and the coming of the New Year is celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis of Sol Invictus, the “Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun,” on December 25.

Saturn the planet and Saturday are both named after the god. Saturn was also among the gods the Romans equated with Yahweh, whose Sabbath (on Saturday) he shared as his holy day. The phrase Saturni dies, “Saturn’s day,” first appears in Latin literature in a poem by Tibullus, who wrote during the reign of Augustus.

The Winter solstice was thought to occur on December 25. January 1 was New Year day: the day was consecrated to Janus since it was the first of the New Year and of the month (kalends) of Janus: the feria had an augural character as Romans believed the beginning of anything was an omen for the whole.

Thus on that day it was customary to exchange cheerful words of good wishes. For the same reason everybody devoted a short time to his usual business, exchanged dates, figs and honey as a token of well wishing and made gifts of coins called strenae. Cakes made of spelt (far) and salt were offered to the god and burnt on the altar.

Ovid states that in most ancient times there were no animal sacrifices and gods were propitiated with offerings of spelt and pure salt. This libum was named ianual and it was probably correspondent to the summanal offered the day before the Summer solstice to god Summanus, which however was sweet being made with flour, honey and milk.

Shortly afterwards, on January 9, on the feria of the Agonium of January the rex sacrorum offered the sacrifice of a ram to Janus.

Baal

Baal, also rendered Baʿal, is a North-West Semitic title and honorific meaning “master” or “lord” that is used for various gods who were patrons of cities in the Levant and Asia Minor, cognate to Akkadian Bēlu. A Baalist or Baalite means a worshipper of Baal.

“Baal” may refer to any god and even to human officials. In some texts it is used for Hadad, a god of thunderstorms, fertility and agriculture, and the lord of Heaven. Since only priests were allowed to utter his divine name, Hadad, Ba‛al was commonly used. . El and Baal are often associated with the bull in Ugaritic texts, as a symbol both of strength and fertility.

The worship of Ba’al in Canaan was bound to the economy of the land which depends on the regularity and adequacy of the rains, unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, which depend on irrigation. Anxiety about the rainfall was a continuing concern of the inhabitants which gave rise to rites to ensure the coming of the rains. Thus the basis of the Ba’al cult was the utter dependence of life on the rains which were regarded as Baal’s bounty. In that respect, Ba’al can be considered a rain god.

El

Ēl (cognate to Akkadian: ilu) is a Northwest Semitic word meaning “deity”. Cognate forms are found throughout the Semitic languages. They include Ugaritic ʾil, pl. ʾlm; Phoenician ʾl pl. ʾlm; Hebrew ʾēl, pl. ʾēlîm; Aramaic ʾl; Akkadian ilu, pl. ilānu.

Elohim and Eloah ultimately derive from the root El, ‘strong’, possibly genericized from El (deity), as in the Ugaritic ’lhm (consonants only), meaning “children of El” (the ancient Near Eastern creator god in pre-Abrahamic tradition).

In the Canaanite religion, or Levantine religion as a whole, El or Il was a god also known as the Father of humanity and all creatures, and the husband of the goddess Asherah as recorded in the clay tablets of Ugarit (modern Ra′s Shamrā, Syria).

In northwest Semitic use, El was both a generic word for any god and the special name or title of a particular god who was distinguished from other gods as being “the god”. El is listed at the head of many pantheons. El is the Father God among the Canaanites.

However, because the word sometimes refers to a god other than the great god Ēl, it is frequently ambiguous as to whether Ēl followed by another name means the great god Ēl with a particular epithet applied or refers to another god entirely. For example, in the Ugaritic texts, ʾil mlk is understood to mean “Ēl the King” but ʾil hd as “the god Hadad”.

The bull was symbolic to El and his son Baʻal Hadad, and they both wore bull horns on their headdress. He may have been a desert god at some point, as the myths say that he had two wives and built a sanctuary with them and his new children in the desert. El had fathered many gods, but most important were Hadad, Yam, and Mot.

Allah/YHWH

The Semitic root ʾlh (Arabic ʾilāh, Aramaic ʾAlāh, ʾElāh, Hebrew ʾelōah) may be ʾl with a parasitic h, and ʾl may be an abbreviated form of ʾlh. In Ugaritic the plural form meaning “gods” is ʾilhm, equivalent to Hebrew ʾelōhîm “powers”. But in Hebrew this word is also regularly used for semantically singular “god”.

The stem ʾl is found prominently in the earliest strata of east Semitic, northwest Semitic, and south Semitic groups. Personal names including the stem ʾl are found with similar patterns in both Amorite and South Arabic which indicates that probably already in Proto-Semitic ʾl was both a generic term for “god” and the common name or title of a single particular god.

As Hebrew and Arabic are closely related Semitic languages, it is commonly accepted that Allah (root, ilāh) and the Biblical Elohim are cognate derivations of same origin, as is Eloah, a Hebrew word which is used (e.g. in the Book of Job) to mean ‘(the) God’ and also ‘god or gods’ as is the case of Elohim.

Allah is the Arabic word for God (al ilāh, iliterally “the God”). The word has cognates in other Semitic languages, including Alah in Aramaic, ʾĒl in Canaanite and Elohim in Hebrew.

It is used mainly by Muslims to refer to God in Islam, but it has also been used by Arab Christians since pre-Islamic times. It is also often, albeit not exclusively, used by Bábists, Bahá’ís, Indonesian and Maltese Christians, and Mizrahi Jews.

Christians and Sikhs in West Malaysia also use and have used the word to refer to God. This has caused political and legal controversies there as the law in West Malaysia prohibited them from using it.

The term Allāh is derived from a contraction of the Arabic definite article al- “the” and ilāh “deity, god” to al-lāh meaning “the [sole] deity, God”. Cognates of the name “Allāh” exist in other Semitic languages, including Hebrew and Aramaic.

The corresponding Aramaic form is Alah, but its emphatic state is Alaha/Ĕlāhā in Biblical Aramaic and Alâhâ in Syriac as used by the Assyrian Church, both meaning simply “God”.

Biblical Hebrew mostly uses the plural (but functional singular) form Elohim, but more rarely it also uses the singular form Eloah. In the Sikh scripture of Guru Granth Sahib, the term Allah is used 37 times.

The name was previously used by pagan Meccans as a reference to a creator deity, possibly the supreme deity in pre-Islamic Arabia. The concepts associated with the term Allah (as a deity) differ among religious traditions.

In pre-Islamic Arabia amongst pagan Arabs, Allah was not considered the sole divinity, having associates and companions, sons and daughters–a concept that was deleted under the process of Islamization.

In Islam, the name Allah is the supreme and all-comprehensive divine name, and all other divine names are believed to refer back to Allah. Allah is unique, the only Deity, creator of the universe and omnipotent. Arab Christians today use terms such as Allāh al-Ab ‘God the Father’) to distinguish their usage from Muslim usage.

There are both similarities and differences between the concept of God as portrayed in the Quran and the Hebrew Bible. It has also been applied to certain living human beings as personifications of the term and concept.

The name Allah or Alla was found in the Epic of Atrahasis engraved on several tablets dating back to around 1700 BC in Babylon, which showed that he was being worshipped as a high deity among other gods who were considered to be his brothers but taking orders from him.

Many inscriptions containing the name Allah have been discovered in Northern and Southern Arabia as early as the 5th century B.C., including Lihyanitic, Thamudic and South Arabian inscriptions.

Dumuzid the Shepherd, a king of the 1st Dynasty of Uruk named on the Sumerian King List, was later over-venerated so that people started associating him with “Alla” and the Babylonian god Tammuz.

The name Allah was used by Nabataeans in compound names, such as “Abd Allah” (The Servant/Slave of Allah), “Aush Allah” (The Faith of Allah), “Amat Allah” (The She-Servant of Allah), “Hab Allah” (Beloved of Allah), “Han Allah” (Allah is gracious), “Shalm Allah” (Peace of Allah), while the name “Wahab Allah” (The Gift of Allah) was found throughout the entire region of the Nabataean kingdom.

From Nabataean inscriptions, Allah seems to have been regarded as a “High and Main God”, while other deities were considered to be mediators before Allah and of a second status, which was the same case of the worshipers at the Kaaba temple at Mecca.

Meccans worshipped him and Al-lāt, Al-‘Uzzá, Manāt as his daughters. Some Jews might considered Uzair to be his son. Christians and Hanifs used the term ‘Bismillah’, ‘in the name of Allah’ and the name Allah to refer to the supreme Deity in Arabic stone inscriptions centuries before Islam.

According to Islamic belief, Allah is the proper name of God, and humble submission to his will, divine ordinances and commandments is the pivot of the Muslim faith. “He is the only God, creator of the universe, and the judge of humankind.” “He is unique (wāḥid) and inherently one (aḥad), all-merciful and omnipotent.” The Qur’an declares “the reality of Allah, His inaccessible mystery, His various names, and His actions on behalf of His creatures.”

In Jewish scripture Elohim is used as a descriptive title for the God of the scriptures, whose personal name is YHWH, Elohim is also used for plural pagan gods. Yahweh was the national god of the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

The name may have originated as an epithet of the god El, head of the Bronze Age Canaanite pantheon (“El who is present, who makes himself manifest”), and appears to have been unique to Israel and Judah, although Yahweh may have been worshiped south of the Dead Sea at least three centuries before the emergence of Israel according to the Kenite hypothesis.

The earliest reference to a deity called “Yahweh” appears in Egyptian texts of the 13th century BC that place him among the Shasu-Bedu of southern Transjordan.

In the oldest biblical literature (12th–11th centuries BC), Yahweh is a typical ancient Near Eastern “divine warrior” who leads the heavenly army against Israel’s enemies; he and Israel are bound by a covenant under which Yahweh will protect Israel and, in turn, Israel will not worship other gods.

At a later period, Yahweh functioned as the dynastic cult (the god of the royal house) with the royal courts promoting him as the supreme god over all others in the pantheon (notably Baal, El, and Asherah (who is thought by some scholars to have been his consort).

Over time, Yahwism became increasingly intolerant of rivals, and the royal court and temple promoted Yahweh as the god of the entire cosmos, possessing all the positive qualities previously attributed to the other gods and goddesses.

With the work of Second Isaiah (the theoretical author of the second part of the Book of Isaiah) towards the end of the Babylonian exile (6th century BC), the very existence of foreign gods was denied, and Yahweh was proclaimed as the creator of the cosmos and the true god of all the world.

By early post-biblical times, the name of Yahweh had ceased to be pronounced. In modern Judaism, it is replaced with the word Adonai, meaning Lord, and is understood to be God’s proper name and to denote his mercy. Many Christian Bibles follow the Jewish custom and replace it with “the LORD”.

The Greek Adōnis, an annually-renewed, ever-youthful vegetation god, a life-death-rebirth deity whose nature is tied to the calendar, was a borrowing from the Canaanite / Phoenician language word ʼadōn, meaning “lord”, which is related to Adonai, one of the names used to refer to the god of the Hebrew Bible and still used in Judaism to the present day.

Syrian Adonis is Gauas or Aos, akin to Egyptian Osiris, the Semitic Tammuz and Baal Hadad, the Etruscan Atunis and the Phrygian Attis, all of whom are deities of rebirth and vegetation.

Kumarbi

El was identified by the Hurrians with Sumerian Enlil, and by the Ugaritians with Kumarbi, the chief god of the Hurrians. He is the son of Anu (the sky), and father of the storm-god Teshub.

The Song of Kumarbi or Kingship in Heaven is the title given to a Hittite version of the Hurrian Kumarbi myth, dating to the 14th or 13th century BC. It is preserved in three tablets, but only a small fraction of the text is legible.

The song relates that Alalu, considered to have housed “the Hosts of Sky”, the divine family, because he was a progenitor of the gods, and possibly the father of Earth, was overthrown by Anu who was in turn overthrown by Kumarbi.

The word “Alalu” borrowed from Semitic mythology and is a compound word made up of the Semitic definite article “Al” and the Semitic supreme deity “Alu.” The “u” at the end of the word is a termination to denote a grammatical inflection. Thus, “Alalu” may also occur as “Alali” or “Alala” depending on the position of the word in the sentence. He was identified by the Greeks as Hypsistos. He was also called Alalus.

Alalu was a primeval deity of the Hurrian mythology. After nine years of reign, Alalu was defeated by his son Anu. Anuʻs son Kumarbi also defeated his father, and his son Teshub defeated him, too. Alalu fled to the underworld.

Scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian creation myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

When Anu tried to escape, Kumarbi bit off his genitals and spat out three new gods. In the text Anu tells his son that he is now pregnant with the Teshub, Tigris, and Tašmišu. Upon hearing this Kumarbi spit the semen upon the ground and it became impregnated with two children. Kumarbi is cut open to deliver Tešub. Together, Anu and Teshub depose Kumarbi.

In another version of the Kingship in Heaven, the three gods, Alalu, Anu, and Kumarbi, rule heaven, each serving the one who precedes him in the nine-year reign. It is Kumarbi’s son Tešub, the Weather-God, who begins to conspire to overthrow his father.

From the first publication of the Kingship in Heaven tablets scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian creation myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

Anzu

Anzu was conceived by the pure waters of the Apsu and the wide Earth. Both Anzû and Siris are seen as massive birds who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately seen as a lion-headed eagle (like a reverse griffin).

Anzu was a servant of the chief sky god Enlil, guard of the throne in Enlil’s sanctuary, (possibly previously a symbol of Anu), from whom Anzu stole the Tablet of Destinies, so hoping to determine the fate of all things. In one version of the legend, the gods sent Lugalbanda to retrieve the tablets, who killed Anzu.

In another, Ea and Belet-Ili conceived Ninurta for the purpose of retrieving the tablets. In a third legend, found in The Hymn of Ashurbanipal, Marduk is said to have killed Anzu.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzû is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds. This demon—half man and half bird—stole the “Tablets of Destiny” from Enlil and hid them on a mountaintop.

Anu ordered the other gods to retrieve the tablets, even though they all feared the demon. According to one text, Marduk killed the bird; in another, it died through the arrows of the god Ninurta. The bird is also referred to as Imdugud.

In Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with cosmogony, any theory concerning the coming into existence (or origin) of either the cosmos (or universe), or the so-called reality of sentient beings.

Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of umsimi (which is usually translated “crown” but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the “ideal creative organ.”) “Ham is the Chaldean Anzu, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime,” which parallels the mutilation of Uranos by Kronos and of Set by Horus.

Ninurta

Ninurta (Nin Ur: God of War) in Sumerian and the Akkadian mythology of Assyria and Babylonia, was the god of Lagash, identified with Ningirsu with whom he may always have been identified.

In older transliteration the name is rendered Ninib and Ninip, and in early commentary he was sometimes portrayed as a solar deity. A number of scholars have suggested that either the god Ninurta or the Assyrian king bearing his name (Tukulti-Ninurta I) was the inspiration for the Biblical character Nimrod.

In Nippur, Ninurta was worshiped as part of a triad of deities including his father, Enlil and his mother, Ninlil. In variant mythology, his mother is said to be the harvest goddess Ninhursag. The consort of Ninurta was Ugallu in Nippur and Bau when he was called Ningirsu.

Ninurta often appears holding a bow and arrow, a sickle sword, or a mace named Sharur: Sharur is capable of speech in the Sumerian legend “Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta” and can take the form of a winged lion and may represent an archetype for the later Shedu.

In another legend, Ninurta battles a birdlike monster called Imdugud (Akkadian: Anzû); a Babylonian version relates how the monster Anzû steals the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil. The Tablets of Destiny were believed to contain the details of fate and the future.

Ninurta slays each of the monsters later known as the “Slain Heroes” (the Warrior Dragon, the Palm Tree King, Lord Saman-ana, the Bison-beast, the Mermaid, the Seven-headed Snake, the Six-headed Wild Ram), and despoils them of valuable items such as Gypsum, Strong Copper, and the Magilum boat). Eventually, Anzû is killed by Ninurta who delivers the Tablet of Destiny to his father, Enlil.

The cult of Ninurta can be traced back to the oldest period of Sumerian history. In the inscriptions found at Lagash he appears under his name Ningirsu, “the lord of Girsu”, Girsu being the name of a city where he was considered the patron deity.

Ninurta appears in a double capacity in the epithets bestowed on him, and in the hymns and incantations addressed to him. On the one hand he is a farmer and a healing god who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons; on the other he is the god of the South Wind as the son of Enlil, displacing his mother Ninlil who was earlier held to be the goddess of the South Wind. Enlil’s brother, Enki, was portrayed as Ninurta’s mentor from whom Ninurta was entrusted several powerful Mes, including the Deluge.

He remained popular under the Assyrians: two kings of Assyria bore the name Tukulti-Ninurta. Ashurnasirpal II (883—859 BCE) built him a temple in the then capital city of Kalhu (the Biblical Calah, now Nimrud). In Assyria, Ninurta was worshipped alongside the gods Aššur and Mulissu.

In the astral-theological system Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn, or perhaps as offspring or an aspect of Saturn. In his capacity as a farmer-god, there are similarities between Ninurta and the Greek Titan Kronos, whom the Romans in turn identified with their Titan Saturn.

In the late neo-Babylonian and early Persian period, syncretism seems to have fused Ninurta’s character with that of Nergal. The two gods were often invoked together, and spoken of as if they were one divinity.

Nergal

A certain confusion exists in cuneiform literature between Ninurta (slayer of Asag and wielder of Sharur, an enchanted mace) and Nergal. Nergal has epithets such as the “raging king,” the “furious one,” and the like. A play upon his name—separated into three elements as Ne-uru-gal (lord of the great dwelling) — expresses his position at the head of the nether-world pantheon.

Nergal was a deity worshipped throughout throughout Mesopotamia (Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia) with the main seat of his worship at Cuthah represented by the mound of Tell-Ibrahim.

Nergal’s chief temple at Cuthah bore the name Meslam, from which the god receives the designation of Meslamtaeda or Meslamtaea, “the one that rises up from Meslam”. The name Meslamtaeda/Meslamtaea indeed is found as early as the list of gods from Fara while the name Nergal only begins to appear in the Akkadian period.

Amongst the Hurrians and later Hittites Nergal was known as Aplu (Apollo), a name derived from the Akkadian Apal Enlil, (Apal being the construct state of Aplu) meaning “the son of Enlil”. As God of the plague, he was invoked during the “plague years” during the reign of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma, when this disease spread from Egypt.

Nergal is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as the deity of the city of Cuth (Cuthah): “And the men of Babylon made Succoth-benoth, and the men of Cuth made Nergal” (2 Kings, 17:30). According to the rabbins, his emblem was a cock and Nergal means a “dunghill cock”, although standard iconography pictured Nergal as a lion. He is the son of Enlil and Ninlil.

Nergal’s fiery aspect appears in names or epithets such as Lugalgira, Lugal-banda (Nergal as the fighting-cock), Sharrapu (“the burner,” a reference to his manner of dealing with outdated teachings), Erra, Gibil (though this name more properly belongs to Nusku), and Sibitti or Seven.

Nergal actually seems to be in part a solar deity, sometimes identified with Shamash, but only a representative of a certain phase of the sun. Portrayed in hymns and myths as a god of war and pestilence, Nergal seems to represent the sun of noontime and of the summer solstice that brings destruction, high summer being the dead season in the Mesopotamian annual cycle.

Nergal was also the deity who presides over the netherworld, and who stands at the head of the special pantheon assigned to the government of the dead (supposed to be gathered in a large subterranean cave known as Aralu or Irkalla).

In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal and Allatu/Ereshkigal.

In the late Babylonian astral-theological system Nergal is related to the planet Mars. As a fiery god of destruction and war, Nergal doubtless seemed an appropriate choice for the red planet, and he was equated by the Greeks either to the combative demigod Heracles (Latin Hercules) or to the war-god Ares (Latin Mars) – hence the current name of the planet.

Ordinarily Nergal pairs with his consort Laz. Standard iconography pictured Nergal as a lion, and boundary-stone monuments symbolise him with a mace surmounted by the head of a lion.

In Assyro-Babylonian ecclesiastical art the great lion-headed colossi serving as guardians to the temples and palaces seem to symbolise Nergal, just as the bull-headed colossi probably typify Ninurta.

The worship of Nergal does not appear to have spread as widely as that of Ninurta, but in the late Babylonian and early Persian period, syncretism seems to have fused the two divinities, which were invoked together as if they were identical. Hymns and votive and other inscriptions of Babylonian and Assyrian rulers frequently invoke him, but we do not learn of many temples to him outside of Cuthah.

The Assyrian king Sennacherib speaks of one at Tarbisu to the north of the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, but significantly, although Nebuchadnezzar II (606 BC – 586 BC), the great temple-builder of the neo-Babylonian monarchy, alludes to his operations at Meslam in Cuthah, he makes no mention of a sanctuary to Nergal in Babylon. Local associations with his original seat—Kutha—and the conception formed of him as a god of the dead acted in making him feared rather than actively worshipped.

Being a deity of the desert, god of fire, which is one of negative aspects of the sun, god of the underworld, and also being a god of one of the religions which rivaled Christianity and Judaism, Nergal was sometimes called a demon and even identified with Satan. According to Collin de Plancy and Johann Weyer, Nergal was depicted as the chief of Hell’s “secret police”, and worked as an “an honorary spy in the service of Beelzebub”.

Teshub/Taru

Teshub (also written Teshup or Tešup) was the Hurrian god of sky and storm. He was related to the Hattian Taru. His Hittite and Luwian name was Tarhun (with variant stem forms Tarhunt, Tarhuwant, Tarhunta), although this name is from the Hittite root *tarh- “to defeat, conquer”.

Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

The Hurrian myth of Teshub’s origin—he was conceived when the god Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his father Anu’s genitals, as such it most likely shares a Proto-Indo-European cognate with the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony. Teshub’s brothers are Aranzah (personification of the river Tigris), Ullikummi (stone giant) and Tashmishu.

In the Hurrian schema, Teshub was paired with Hebat the mother goddess; in the Hittite, with the sun goddess Arinniti of Arinna – a cultus of great antiquity which has similarities with the venerated bulls and mothers at Çatalhöyük in the Neolithic era. His son was called Sarruma, the mountain god.

According to Hittite myths, one of Teshub’s greatest acts was the slaying of the dragon Illuyanka. Myths also exist of his conflict with the sea creature (possibly a snake or serpent) Hedammu.

lluyanka is probably a compound, consisting of two words for “snake”, Proto-Indo-European *h₁illu- and *h₂eng(w)eh₂-. The same compound members, inverted, appear in Latin anguilla “eel”. The *h₁illu- word is cognate to English eel, the anka- word to Sanskrit ahi. Also this dragon is known as Illujanka and Illuyankas.

The Hittite texts were introduced in 1930 by W. Porzig, who first made the comparison of Teshub’s battle with Illuyankas with the sky-god Zeus’ battle with serpent-like Typhon, told in Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke (I.6.3); the Hittite-Greek parallels found few adherents at the time, the Hittite myth of the castration of the god of heaven by Kumarbi, with its clearer parallels to Greek myth, not having yet been deciphered and edited.

In the early Vedic religion, Vritra (Vṛtra वृत्र “the enveloper”), is an Asura and also a serpent or dragon, the personification of drought and adversary of Indra. Vritra was also known in the Vedas as Ahi (“snake”). He appears as a dragon blocking the course of the rivers and is heroically slain by Indra.

Tork Angegh

In Armenian Tor has two meanings 1. grandson, q is the plural form, so torq is grandsons or heirs, 2. rain. In Armenian Artsax Dialect Tor means rain, tora kyalis (galis) means it rains.

Tork Angegh (Armenian: Տորք Անգեղ) was an ancient Armenian masculine deity of strength, courage, of manufacturing and the arts, also called Torq and Durq/Turq. A creature of unnatural strength and power, Tork was considered one of Hayk’s great-grandsons and reportedly represented as an unattractive male figure.

He is mentioned by Armenian 4th Century historian Movses Khorenatsi and considered one of the significant deities of the Armenian pantheon prior to the time when it came under influence by Iranian and Hellenic religion and mythology.

According to the Armenian legend, Torq (Turq) Angegh was a deity, the son of Angegh and the Grandson of Hayk. Moreover, in historical Armenia there is a place (region) known as Ang'(e)gh, probably named after the father of Torq. Their symbol was ang'(e)gh (a vulture) and they were called – Ang'(e)gh tohmi jarangnere, the heirs of the house of vultures. To(u)rq Angegh has a lot to do with rain and storm, but at the same time he was described as a man living in ancient Armenia, Armenian deity.

Only after christianity Torq Angegh got negative meaning and became ugly. Everything predating 301 AD is ugly, this way they made the Armenians be ashamed of thier heritage but anyway, the historical memory never forgets the past, the Armenians call Torq Angeg to the ones who are bigger, who may have had exaggerated features.

Torq was worshipped in historical Armenian territory known as Tegarama or Togorma. The word angel derives from angegh, which is the same as the Sumerian gal, meaning great.

Angels came to the people as birds, angels are with wings. The angels are the derivation of the bird angegh which means vulture. This bird was worshipped among Armenians and considered to be sacred.

Torq was a deity of storm, rain and thunder. They believe, he threw a huge stone in the sea and the ships of the enemies of his people got drowned. The Armenians have an expression փոթորիկ անել “potorik anel” which means to make storms.

Taken in the context of Proto-Indo-European religions, it is conceivable that an etymological connection with Norse god Thor/Tyr is more than a simple coincidence. An analogy is frequently made with the Middle-Eastern god Nergal, also represented as an unattractive male.

Odin/Thor

Odin (from Old Norse Óðinn, “The Furious One”) is a major god in Germanic mythology, especially in Norse mythology. In many Norse sources he is the Allfather of the gods and the ruler of Asgard. Homologous with the Old English “Wōden”, the Old Saxon “Wôdan” and the Old High German “Wôtan”, the name is descended from Proto-Germanic “Wōdanaz” or “*Wōđanaz”.

“Odin” is generally accepted as the modern English form of the name, although, in some cases, older forms may be used or preferred. His name is related to ōðr, meaning “fury, excitation”, besides “mind” or “poetry”. His role, like that of many of the Norse gods, is complex.

Odin is a principal member of the Æsir (the major group of the Norse pantheon) and is associated with war, battle, victory and death, but also wisdom, Shamanism, magic, poetry, prophecy, and the hunt. Odin has many sons, the most famous of whom is the thunder god Thor.

Indra

Indra, also known as Śakra in the Vedas, is the leader of the Devas or demi gods and the lord of Svargaloka or heaven in Hinduism. He is the god of rain and thunderstorms. He wields a lightning thunderbolt known as vajra and rides on a white elephant known as Airavata.

Indra is the supreme deity and is the twin brother of Agni and is also mentioned as an Āditya, son of Aditi. His home is situated on Mount Meru in the heaven. He has many epithets, notably vṛṣan the bull, and vṛtrahan, slayer of Vṛtra, Meghavahana “the one who rides the clouds” and Devapati “the lord of gods or devas”.

Indra appears as the name of a daeva in Zoroastrianism (but please note that word Indra can be used in general sense as a leader, either of devatas or asuras), while his epithet, Verethragna, appears as a god of victory. Indra is also called Śakra frequently in the Vedas and in Buddhism (Pali: Sakka).

He is celebrated as a demiurge who pushes up the sky, releases Ushas (dawn) from the Vala cave, and slays Vṛtra; both latter actions are central to the Soma sacrifice. He is associated with Vajrapani – the Chief Dharmapala or Defender and Protector of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha who embodies the power of the Five Dhyani Buddhas.

On the other hand, he also commits many kinds of mischief (kilbiṣa) for which he is sometimes punished. In Puranic mythology, Indra is bestowed with a heroic and almost brash and amorous character at times, even as his reputation and role diminished in later Hinduism with the rise of the Trimurti.

Zeus

Zeus is the “Father of Gods and men” who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter.

Zeus is the Greek continuation of *Di̯ēus, the name of the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also called *Dyeus ph2tēr (“Sky Father”). The god is known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic Sanskrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European vocative *dyeu-ph2tēr), deriving from the root *dyeu- (“to shine”, and in its many derivatives, “sky, heaven, god”).

Zeus is the only deity in the Olympic pantheon whose name has such a transparent Indo-European etymology. The earliest attested forms of the name are the Mycenaean Greek di-we and di-wo, written in the Linear B syllabic script.

Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.

He is known for his erotic escapades. These resulted in many godly and heroic offspring, including Athena, Apollo and Artemis, Hermes, Persephone (by Demeter), Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses (by Mnemosyne); by Hera, he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe and Hephaestus.

As Walter Burkert points out in his book, Greek Religion, “Even the gods who are not his natural children address him as Father, and all the gods rise in his presence.” For the Greeks, he was the King of the Gods, who oversaw the universe.

As Pausanias observed, “That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men”. In Hesiod’s Theogony Zeus assigns the various gods their roles. In the Homeric Hymns he is referred to as the chieftain of the gods.

His symbols are the thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak. In addition to his Indo-European inheritance, the classical “cloud-gatherer” (Greek: Nephelēgereta) also derives certain iconographic traits from the cultures of the Ancient Near East, such as the scepter. Zeus is frequently depicted by Greek artists in one of two poses: standing, striding forward, with a thunderbolt leveled in his raised right hand, or seated in majesty.

Tyr

Týr is a god associated with law and heroic glory in Norse mythology, portrayed as one-handed. Corresponding names in other Germanic languages are Gothic Teiws, Old English Tīw and Old High German Ziu and Cyo, all from Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz. The Latinised name is Tius or Tio.

Old Norse Týr, literally “god”, plural tívar “gods”, comes from Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz (cf. Old English Tīw, Old High German Zīo), which continues Proto-Indo-European *deiwós “celestial being, god” (cf. Welsh duw, Latin deus, Lithuanian diẽvas, Sanskrit dēvá, Avestan daēvō “demon”). And *deiwós is based in *dei-, *deyā-, *dīdyā-, meaning ‘to shine’.

In the late Icelandic Eddas, Tyr is portrayed, alternately, as the son of Odin (Prose Edda) or of Hymir (Poetic Edda), while the origins of his name and his possible relationship to Tuisto suggest he was once considered the father of the gods and head of the pantheon, since his name is ultimately cognate to that of *Dyeus (cf. Dyaus), the reconstructed chief deity in Indo-European religion. It is assumed that Tîwaz was overtaken in popularity and in authority by both Odin and Thor at some point during the Migration Age, as Odin shares his role as God of war.

Comparative mythology

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. These closely parallel two ancient Indo-European conceptions of justice represented by the one-eyed sovereign (wild, unreliable, ruling through bravado) and the one-handed sovereign (solemn, proper, ruling by the letter of the law).

These conceptions of justice and their attendant myths were originally described at length by prominent philologist Georges Dumezil (1898-1986) in his 1948 book Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty.

The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

In Nordic mythology, for example, a young wolf named Fenrir is thought (by shrewd prognosticators attuned to supernatural wolf strength) to be capable of destroying the world of the gods. The one-eyed god Odhinn thus tries to get Fenrir to submit to a leash. This he does through deceit: Odhinn presents the leashing as a challenge—see how long it takes you to get out of it. The savvy wolf suspects, correctly, that the leash is magic and will subdue him for eternity. So as a gesture of goodwill, Tyr, a god representing the rule of law, offers to put his hand in Fenrir’s mouth as a pledge to the wolf that there is no hocus-pocus afoot—if Fenrir cannot get out of the leash, Tyr will lose his hand. The wolf submits, the world is saved, but at the cost of Tyr’s hand.

In Roman mytho-history (Romans liked to give their history a mythic burnish), one-eyed Horatio Cocles (“Cocles” being derived from “Cyclops”) and soon to be one-handed Mucius Scaevola team up to defeat Lars Porsenna, an invading Etruscan determined to sack Rome.

According to Dumzeil, the one-eyed Cocles “holds the enemy in check by his strangely wild behavior.” Citing the Roman historian Livy, Dumezil writes that “remaining alone at the entrance to the bridge, [Cocles] casts terrible and menacing looks at the Etruscan leaders, challenging them individually, insulting them collectively.” He also deploys “terrible grimaces.”

Cocles’ antics stop Porsenna temporarily, but the surly Etruscan soon brings war upon Rome again, and this time it’s Scaevola, whose mind ran in a more statesmanlike track than his comrade Cocles, to the rescue. He warns Porsenna that he has 300 assassins at his disposal—it’s a bluff, but Scaevola burns his hand in a fire to convince his enemy his threat is bona fide. Porsenna agrees to leave Rome.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

Dumézil compares Varuna and Mitra with other figures like the gods Savitr (the creative initiater of movement, who is connected with night and dusk) and Bhaga (the fair distributer, who is connected with dawn and midday) of India, the Germanic deities Odin (mystical) and Tyr (prudent), the early Roman kings Romulus (unpredictable founder) and Numa (conservative legislator), and the Irish-Celtic gods Lugus (name derived from proto-Celtic for “oath”) and Nodens (the derivation of this name is uncertain).

A strange motif of unclear meaning involving eyes and hands also plays a role in this concept and extends the metaphor to other figures and stories. While there is nothing particularly significant involving the eyes and hands of Mitra and Varuna (or indeed Romulus and Numa), Odin and Lugus are both one-eyed gods and Tyr and Nodens are both one-handed.

Tyr is probably the oldest of the Germanic deities, his name being an abbreviated form of Tiwaz, which derives from the same PIE word that gave us Zeus, Dios, deus, and theos. Tyr is regarded as the father of the Germanic pantheon while Nodens was the original ruler of the Tuatha de Dannan, a legendary race of people who conquered Ireland from the Fir Bolg. Additionally, two early Roman heroes, Horatius Cocles and Mucius Scaevola, are respectively one-eyed and one-handed.

Zeus seized power from his father Cronos with the assistance of Cyclopes and strange hundred-handed creatures (it is worth noting as well that Cronos governed the world without laws while Zeus provided order; there is a legend that Romulus was killed by leading aristocrats due to his arbitrary rulership and replaced with Numa to bring stability).

In the cases of Cocles and Lugus, their eyes were lost in battle while both Scaevola and Tyr were required to sacrifice their hands to uphold oaths. These early Romans are typically regarded as being at least partially historical, but it seems clear that these ancient legends were superimposed upon the real figures for the purposes of narrative.

Gaius Mucius Scaevola

Gaius Mucius Scaevola was a Roman youth, famous for his bravery. In 508 BC, during the war between Rome and Clusium, the Clusian king Lars Porsena laid siege to Rome. Mucius, with the approval of the Roman Senate sneaked into the Etruscan camp and attempted to murder Porsena. It was the soldiers’ pay day. There were two similarly dressed people on a raised platform talking to the troops. He misidentified Porsena and killed Porsena’s scribe instead.

Mucius was captured, and famously declared to Porsena: “I am Gaius Mucius, a citizen of Rome. I came here as an enemy to kill my enemy, and I am as ready to die as I am to kill. We Romans act bravely and, when adversity strikes, we suffer bravely.” He also declared that he was the first of three hundred Roman youths who volunteered to assassinate Porsena at the risk of their own lives.

“Watch this,” he declared. “so that you know how cheap the body is to men who have their eye on great glory.” Mucius thrust his right hand into a fire which was lit for sacrifice and held it there without giving any indication of pain, thereby earning for himself and his descendants the cognomen Scaevola, meaning ‘left-handed’.

Porsena, shocked at the youth’s bravery, dismissed him from the Etruscan camp, free to return to Rome saying “Go back, since you do more harm to yourself than me”. At the same time, the king also sent ambassadors to Rome to offer peace.

Mucius was granted farming land on the right-hand bank of the Tiber, which later became known as the Mucia Prata (Mucian Meadows). It is not clear whether the story of Mucius is historical or mythical.

Mars/Ares

Tiw was equated with Mars (Latin: Mārs, Martis), in ancient Roman religion and myth the god of war and also an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome, in the interpretatio germanica. Tuesday is in fact “Tīw’s Day” (also in Alemannic Zischtig from zîes tag), translating dies Martis. He was second in importance only to Jupiter and Neptune and he was the most prominent of the military gods in the religion of the Roman army.

Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him (Latin Martius), and in October, which began the season for military campaigning and ended the season for farming.

Under the influence of Greek culture, Mars was identified with the Greek god Ares, whose myths were reinterpreted in Roman literature and art under the name of Mars. But the character and dignity of Mars differed in fundamental ways from that of his Greek counterpart, who is often treated with contempt and revulsion in Greek literature.

Ares is the Greek god of war. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. In Greek literature, he often represents the physical or violent and untamed aspect of war, in contrast to the armored Athena, whose functions as a goddess of intelligence include military strategy and generalship.

Although Ares was viewed primarily as a destructive and destabilizing force, Mars represented military power as a way to secure peace, and was a father (pater) of the Roman people.

In the mythic genealogy and founding myths of Rome, Mars was the father of Romulus and Remus with Rhea Silvia. His love affair with Venus symbolically reconciled the two different traditions of Rome’s founding; Venus was the divine mother of the hero Aeneas, celebrated as the Trojan refugee who “founded” Rome several generations before Romulus laid out the city walls.

The importance of Mars in establishing religious and cultural identity within the Roman Empire is indicated by the vast number of inscriptions identifying him with a local deity, particularly in the Western provinces.

During the Hellenization of Latin literature, the myths of Ares were reinterpreted by Roman writers under the name of Mars. Greek writers under Roman rule also recorded cult practices and beliefs pertaining to Mars under the name of Ares. Thus in the classical tradition of later Western art and literature, the mythology of the two figures becomes virtually indistinguishable.

Sumerian

Northwest Semitic

Life-death-rebirth deity

Thunder gods

Stone gigant

Snake

Decayed Gods

Decayed Gods: Origin and Development of Georges Dumézil’s “Idéologie Tripartie”

Filed under: Uncategorized

Enki and Saturn – The Capricorn

Enlil, wind god, with his thunderbolts pursues Anzu after Anzu stole the Tablets of Destiny (from Austen Henry Layard Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853)

Anu – Enki/Enlil/Haya – Marduk (Sumerian)

Anu – Kumarbi – Teshub (Hurrian)

Anu – El/Dagon – Baal/Haddad/Adad (Semitic)

Uranus – Cronus – Zeus (Greek)

Caelus – Saturn/Janus/Portunus – Jupiter (Roman)

Tefnut/Shu – Ptah/Geb – Nefertem (Egypt)

Nu (the abyss) – Ra/Atum -

Tefnut/Shu – Geb/Nut (Neuth) – Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys and Horus (Egypt)

The trifunctional hypothesis

The trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society postulates a tripartite ideology (“idéologie tripartite”) reflected in the existence of three classes or castes—priests, warriors, and commoners (farmers or tradesmen) – corresponding to the three functions of the sacral, the martial and the economic, respectively.

This thesis is especially associated with the French mythographer Georges Dumézil who proposed it in 1929 in the book Flamen-Brahman, and later in Mitra-Varuna.

Dumézil postulated a split of the figure of the sovereign god in Indoeuropean religion, which is embodied by Vedic gods Varuna and Mitra. Of the two, the first one shows the aspect of the magic, uncanny, awe inspiring power of creation and destruction, while the second shows the reassuring aspect of guarantor of the legal order in organised social life.

Whereas in Jupiter these double features have coalesced, Briquel sees Saturn as showing the characters of a sovereign god of the Varunian type. His nature becomes evident in his mastership over the annual time of crisis around the winter solstice, epitomised in the power of subverting normal codified social order and its rules, which is apparent in the festival of the Saturnalia, in the mastership of annual fertility and renewal, in the power of annihilation present in his paredra Lua, in the fact that he is the god of a timeless era of plenty and bounty before time, which he reinstates at the time of the yearly crisis of the winter solstice.

Also, in Roman and Etruscan reckoning Saturn is a wielder of lightning; no other agricultural god (in the sense of specialized human activity) is one. Hence the mastership he has on agriculture and wealth cannot be that of a god of the third function, i.e. of production, wealth, and pleasure, but it stems from his magical lordship over creation and destruction.

Although these features are to be found in Greek god Cronus as well, it looks they were proper to the most ancient Roman representations of Saturn, such as his presence on the Capitol and his association with Jupiter, who in the stories of the arrival of the Pelasgians in the land of the Sicels and that of the Argei orders human sacrifices to him.

Sacrifices to Saturn were performed according to “Greek rite” (ritus graecus), with the head uncovered, in contrast to those of other major Roman deities, which were performed capite velato, “with the head covered.”

Saturn himself, however, was represented as veiled (involutus), as for example in a wall painting from Pompeii that shows him holding a sickle and covered with a white veil. This feature is in complete accord with the character of a sovereign god of the Varunian type and is common with German god Odin.

Briquel remarks Servius had already seen that the choice of the Greek rite was due to the fact that the god himself is imagined and represented as veiled, thence his sacrifice cannot be carried out by a veiled man: this is an instance of the reversal of the current order of things typical of the nature of the deity as appears in its festival. Plutarch writes his figure is veiled because he is the father of truth.

Pliny notes that the cult statue of Saturn was filled with oil; the exact meaning of this is unclear. Its feet were bound with wool, which was removed only during the Saturnalia. The fact that the statue was filled with oil and the feet were bound with wool may relate back to the myth of “The Castration of Uranus”. In this myth Rhea gives Cronus a rock to eat in Zeus’ stead thus tricking Cronus.

Although mastership of knots is a feature of Greek origin it is also typical of the Varunian sovereign figure, as apparent e.g. in Odin. Once Zeus was victorious over Cronus, he sets this stone up at Delphi and constantly it is anointed with oil and strands of unwoven wool are placed on it. It wore a red cloak, and was brought out of the temple to take part in ritual processions and lectisternia, banquets at which images of the gods were arranged as guests on couches.

All these ceremonial details identify a sovereign figure. Briquel concludes that Saturn was a sovereign god of a time that the Romans perceived as no longer actual, that of the legendary origins of the world, before civilization.

Little evidence exists in Italy for the cult of Saturn outside Rome, but his name resembles that of the Etruscan god Satres. The potential cruelty of Saturn was enhanced by his identification with Cronus, known for devouring his own children. He was thus equated with the Carthaginian god Ba’al Hammon, to whom children were sacrificed.

Later this identification gave rise to the African Saturn, a cult that enjoyed great popularity til the 4th century. It had a popular but also a mysteric character and required child sacrifices. It is also considered as inclining to monotheism.

In the ceremony of initiation the myste intrat sub iugum, ritual that Leglay compares to the Roman tigillum sororium. Even though their origin and theology are completely different the Italic and the African god are both sovereign and master over time and death, fact that has permitted their encounter. Moreover here Saturn is not the real Italic god but his Greek counterpart Cronus.

Saturn was also among the gods the Romans equated with Yahweh, whose Sabbath (on Saturday) he shared as his holy day. The phrase Saturni dies, “Saturn’s day,” first appears in Latin literature in a poem by Tibullus, who wrote during the reign of Augustus.

Theogony

Teshub (also written Teshup or Tešup) was the Hurrian god of sky and storm. Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

The Hurrian myth of Teshub’s origin—he was conceived when the god Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his father Anu’s genital, as such it most likely shares a Proto-Indo-European cognate with the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony.

In ancient myth recorded by Hesiod’s Theogony, Cronus envied the power of his father, the ruler of the universe, Uranus. Uranus drew the enmity of Cronus’ mother, Gaia, when he hid the gigantic youngest children of Gaia, the hundred-handed Hecatonchires and one-eyed Cyclopes, in the Tartarus, so that they would not see the light. Gaia created a great stone sickle and gathered together Cronus and his brothers to persuade them to castrate Uranus.

Only Cronus was willing to do the deed, so Gaia gave him the sickle and placed him in ambush. When Uranus met with Gaia, Cronus attacked him with the sickle, castrating him and casting his testicles into the sea.

From the blood that spilled out from Uranus and fell upon the earth, the Gigantes, Erinyes, and Meliae were produced. The testicles produced the white foam from which the goddess Aphrodite emerged.

For this, Uranus threatened vengeance and called his sons Titenes (according to Hesiod meaning “straining ones,” the source of the word “titan”, but this etymology is disputed) for overstepping their boundaries and daring to commit such an act.

In an alternate version of this myth, a more benevolent Cronus overthrew the wicked serpentine Titan Ophion. In doing so, he released the world from bondage and for a time ruled it justly.

After dispatching Uranus, Cronus re-imprisoned the Hecatonchires, and the Cyclopes and set the dragon Campe to guard them. He and his sister Rhea took the throne of the world as king and queen. The period in which Cronus ruled was called the Golden Age, as the people of the time had no need for laws or rules; everyone did the right thing, and immorality was absent.

Cronus learned from Gaia and Uranus that he was destined to be overcome by his own sons, just as he had overthrown his father. As a result, although he sired the gods Demeter, Hestia, Hera, Hades and Poseidon by Rhea, he devoured them all as soon as they were born to prevent the prophecy.

When the sixth child, Zeus, was born Rhea sought Gaia to devise a plan to save them and to eventually get retribution on Cronus for his acts against his father and children. Another child Cronus is reputed to have fathered is Chiron, by Philyra.

Rhea secretly gave birth to Zeus in Crete, and handed Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, also known as the Omphalos Stone, which he promptly swallowed, thinking that it was his son.

Rhea kept Zeus hidden in a cave on Mount Ida, Crete. According to some versions of the story, he was then raised by a goat named Amalthea, while a company of Kouretes, armored male dancers, shouted and clapped their hands to make enough noise to mask the baby’s cries from Cronus.

Other versions of the myth have Zeus raised by the nymph Adamanthea, who hid Zeus by dangling him by a rope from a tree so that he was suspended between the earth, the sea, and the sky, all of which were ruled by his father, Cronus. Still other versions of the tale say that Zeus was raised by his grandmother, Gaia.

Once he had grown up, Zeus used an emetic given to him by Gaia to force Cronus to disgorge the contents of his stomach in reverse order: first the stone, which was set down at Pytho under the glens of Mount Parnassus to be a sign to mortal men, and then his two brothers and three sisters.

In other versions of the tale, Metis gave Cronus an emetic to force him to disgorge the children, or Zeus cut Cronus’ stomach open. After freeing his siblings, Zeus released the Hecatonchires, and the Cyclopes who forged for him his thunderbolts, Poseidon’s trident and Hades’ helmet of darkness.

In a vast war called the Titanomachy, Zeus and his brothers and sisters, with the help of the Hecatonchires, and Cyclopes, overthrew Cronus and the other Titans. Afterwards, many of the Titans were confined in Tartarus, however, Atlas, Epimetheus, Menoetius, Oceanus and Prometheus were not imprisoned following the Titanomachy. Gaia bore the monster Typhon to claim revenge for the imprisoned Titans.

Accounts of the fate of Cronus after the Titanomachy differ. In Homeric and other texts he is imprisoned with the other Titans in Tartarus. In Orphic poems, he is imprisoned for eternity in the cave of Nyx. Pindar describes his release from Tartarus, where he is made King of Elysium by Zeus.

In another version, the Titans released the Cyclopes from Tartarus, and Cronus was awarded the kingship among them, beginning a Golden Age. In Virgil’s Aeneid, it is Latium to which Saturn (Cronus) escapes and ascends as king and lawgiver, following his defeat by his son Jupiter (Zeus).

One other account referred by Robert Graves (who claims to be following the account of the Byzantine mythographer Tzetzes) it is said that Cronus was castrated by his son Zeus just like he had done with his father Uranus before.

However the subject of a son castrating his own father, or simply castration in general, was so repudiated by the Greek mythographers of that time that they suppressed it from their accounts until the Christian era (when Tzetzes wrote).

The one-handed god and the one-eyed sovereign

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. These closely parallel two ancient Indo-European conceptions of justice represented by the one-eyed sovereign (wild, unreliable, ruling through bravado) and the one-handed sovereign (solemn, proper, ruling by the letter of the law).

These conceptions of justice and their attendant myths were originally described at length by prominent philologist Georges Dumezil (1898-1986) in his 1948 book Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty.

The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

Dumezil observed that a wide range of Indo-European cultures produced myths—philologically related to one another—in which the universe was governed by one-eyed and one-handed gods acting in concert. The one-eyed gods tended to rule though magic, strong personalities, and mad bravado. The one-handed gods, by contrast, represented the rule of law—the ordering and arrangement of society through contracts, covenants, and statutes.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

In Nordic mythology, for example, a young wolf named Fenrir is thought (by shrewd prognosticators attuned to supernatural wolf strength) to be capable of destroying the world of the gods. The one-eyed god Odhinn thus tries to get Fenrir to submit to a leash. This he does through deceit: Odhinn presents the leashing as a challenge—see how long it takes you to get out of it. The savvy wolf suspects, correctly, that the leash is magic and will subdue him for eternity. So as a gesture of goodwill, Tyr, a god representing the rule of law, offers to put his hand in Fenrir’s mouth as a pledge to the wolf that there is no hocus-pocus afoot—if Fenrir cannot get out of the leash, Tyr will lose his hand. The wolf submits, the world is saved, but at the cost of Tyr’s hand.

In Roman mytho-history (Romans liked to give their history a mythic burnish), one-eyed Horatio Cocles (“Cocles” being derived from “Cyclops”) and soon to be one-handed Mucius Scaevola team up to defeat Lars Porsenna, an invading Etruscan determined to sack Rome.

According to Dumzeil, the one-eyed Cocles “holds the enemy in check by his strangely wild behavior.” Citing the Roman historian Livy, Dumezil writes that “remaining alone at the entrance to the bridge, [Cocles] casts terrible and menacing looks at the Etruscan leaders, challenging them individually, insulting them collectively.” He also deploys “terrible grimaces.”

Cocles’ antics stop Porsenna temporarily, but the surly Etruscan soon brings war upon Rome again, and this time it’s Scaevola, whose mind ran in a more statesmanlike track than his comrade Cocles, to the rescue. He warns Porsenna that he has 300 assassins at his disposal—it’s a bluff, but Scaevola burns his hand in a fire to convince his enemy his threat is bona fide. Porsenna agrees to leave Rome.

In many narratives, the one-handed god loses his hand or arm after breaking a contract or reneging on a deal—illustrating the idea that in times of crisis, the law must be bent or broken, though the price for doing so can be dear.

Dumézil compares Varuna and Mitra with other figures like the gods Savitr (the creative initiater of movement, who is connected with night and dusk) and Bhaga (the fair distributer, who is connected with dawn and midday) of India, the Germanic deities Odin (mystical) and Tyr (prudent), the early Roman kings Romulus (unpredictable founder) and Numa (conservative legislator), and the Irish-Celtic gods Lugus (name derived from proto-Celtic for “oath”) and Nodens (the derivation of this name is uncertain).

A strange motif of unclear meaning involving eyes and hands also plays a role in this concept and extends the metaphor to other figures and stories. While there is nothing particularly significant involving the eyes and hands of Mitra and Varuna (or indeed Romulus and Numa), Odin and Lugus are both one-eyed gods and Tyr and Nodens are both one-handed.

Tyr is probably the oldest of the Germanic deities, his name being an abbreviated form of Tiwaz, which derives from the same PIE word that gave us Zeus, Dios, deus, and theos. Tyr is regarded as the father of the Germanic pantheon while Nodens was the original ruler of the Tuatha de Dannan, a legendary race of people who conquered Ireland from the Fir Bolg. Additionally, two early Roman heroes, Horatius Cocles and Mucius Scaevola, are respectively one-eyed and one-handed.

Zeus seized power from his father Cronos with the assistance of Cyclopes and strange hundred-handed creatures (it is worth noting as well that Cronos governed the world without laws while Zeus provided order; there is a legend that Romulus was killed by leading aristocrats due to his arbitrary rulership and replaced with Numa to bring stability).

In the cases of Cocles and Lugus, their eyes were lost in battle while both Scaevola and Tyr were required to sacrifice their hands to uphold oaths. These early Romans are typically regarded as being at least partially historical, but it seems clear that these ancient legends were superimposed upon the real figures for the purposes of narrative.

Gugalanna

Gu or gud means ox, bull. In Mesopotamian mythology, Gugalanna (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”) was a Sumerian deity as well as the constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies.