![]()

Khaldi (the god of war)

![]()

Hel (the goddess of the underworld)

The ancient Greeks and Romans knew of only five ‘wandering stars': Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Following the discovery of a sixth planet in the 18th century, the name Uranus was chosen as the logical addition to the series: for Mars (Ares in Greek) was the son of Jupiter, Jupiter (Zeus in Greek) the son of Saturn, and Saturn (Cronus in Greek) the son of Uranus. What is anomalous is that, while the others take Roman names, Uranus is a name derived from Greek in contrast to the Roman Caelus.

Ereshkigal – “The great lady under earth”

The Queen of Heaven

Descent to the underworld

Inanna (life/spring) and Ereskigal (death/autumn)

Similarities in the Sumerian and the Egyptian mythologies

Januar (Hel) – the beginning or the end?

The Norse Goddess Hel

List of sky deities

The supreme God in various nations

Irkalla

In Babylonian mythology, Irkalla (also Ir-Kalla, Irkalia) is the underworld from which there is no return. It is also called Arali, Kigal, Gizal, and the lower world. Irkalla is ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal and her consort, the death god Nergal.

Ereshkigal

In Mesopotamian mythology, Ereshkigal (DEREŠ.KI.GAL, lit. “great lady under earth”) was the goddess of Irkalla, the land of the dead or underworld, also called Arali, Kigal, Gizal, and the lower world. Irkalla is ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal and her consort, the death god Nergal. Sometimes her name is given as Irkalla, similar to the way the name Hades was used in Greek mythology for both the underworld and its ruler.

Ereshkigal was the only one who could pass judgment and give laws in her kingdom. The main temple dedicated to her was located in Kutha (Sumerian: Gudua, modern Tell Ibrahim). In Mesopotamian mythology, Gugalanna (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”) was a Sumerian deity as well as the constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and warfare, and goddess of the E-Anna temple at the city of Uruk (Eresh), her main centre.

Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies.

Gugalanna was the first husband of the Goddess Ereshkigal, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, a gloomy place devoid of light. It was to share the sorrow with her sister that Inanna later descends to the Underworld.

Taurus was a constellation of the Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox from about 3,200 BCE. It marked the start of the agricultural year with the New Year Akitu festival (from á-ki-ti-še-gur10-ku5, = sowing of the barley), an important date in Mespotamian religion. The death of Gugalanna represents the obscuring disappearance of this constellation as a result of the light of the sun, with whom Gilgamesh was identified.

In the time in which this myth was composed, the Akitu festival at the Spring Equinox, due to the Precession of the Equinoxes did not occur in Aries, but in Taurus. At this time of the year, Taurus would have disappeared as it was obscured by the sun.

“Between the period of the earliest female figurines circa 4500 B.C. … a span of a thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilised by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth. Moreover by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and the laws of sky and earth.”

The goddess Inanna (Ninana) refers to Ereshkigal as her older sister in the Sumerian hymn “The Descent of Inanna” (which was also in later Babylonian myth, also called “The Descent of Ishtar”). Inanna/Ishtar’s trip and return to the underworld is the most familiar of the myths concerning Ereshkigal.

Ereshkigal is the sister and counterpart of Inanna/Ishtar, the symbol of nature during the non-productive season of the year. Ereshkigal was also a queen that many gods and goddesses looked up to in the underworld. She is known chiefly through two myths, believed to symbolize the changing of the seasons, but perhaps also intended to illustrate certain doctrines which date back to the Mesopotamia period. According to the doctrine of two kingdoms, the dominions of the two sisters are sharply differentiated, as one is of this world and one of the world of the dead.

One of these myths is Inanna’s descent to the netherworld and her reception by her sister who presides over it; Ereshkigal traps her sister in her kingdom and Inanna is only able to leave it by sacrificing her husband Dumuzi in exchange for herself.

The other myth is the story of Nergal, the plague god. Once, the gods held a banquet that Ereshkigal as queen of the Netherworld cannot come up to attend. They invite her to send a messenger and she sends Namtar, her vizier. He is treated well by all but disrespected by Nergal.

As a result of this, Nergal is banished to the kingdom controlled by the goddess. Versions vary at this point, but all of them result in him becoming her husband. In later tradition, Nergal is said to have been the victor, taking her as wife and ruling the land himself.

It is theorized that the story of Inanna’s descent is told to illustrate the possibility of an escape from the netherworld, while the Nergal myth is intended to reconcile the existence of two rulers of the netherworld: a goddess and a god.

The addition of Nergal represents the harmonizing tendency to unite Ereshkigal as the queen of the netherworld with the god who, as god of war and of pestilence, brings death to the living and thus becomes the one who presides over the dead.

In some versions of the myths, she rules the underworld by herself, sometimes with a husband subordinate to her named Gugalana. It was said that she had been stolen away by Kur and taken to the underworld, where she was made queen unwillingly.

She is the mother of the goddess Nungal, a goddess of the underworld. Her son with Enlil was the god Namtar (or Namtaru, or Namtara; meaning destiny or fate). With Gugalana her son was Ninazu, a god of the underworld, and of healing.

Ningishzida (sum: dnin-g̃iš-zid-da) is a Mesopotamian deity of the underworld. His name in Sumerian is translated as “lord of the good tree” by Thorkild Jacobsen.

In Sumerian mythology, he appears in Adapa’s myth as one of the two guardians of Anu’s celestial palace, alongside Dumuzi or Tammuz (Akkadian: Duʾzu, Dūzu; Sumerian: Dumuzid (DUMU.ZI(D), “faithful or true son”), the name of a Sumerian god of food and vegetation, also worshiped in the later Mesopotamian states of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia.

Ningishzida was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head. He is sometimes the son of Ninazu and Ningiridda, even though the myth Ningishzidda’s journey to the netherworld suggests he is the son of Ereshkigal. Following an inscription found at Lagash, he was the son of Anu, the heavens.

His wife is Azimua, one of the eight deities born to relieve the illness of Enki, and also Geshtinanna, while his sister is Amashilama. In some texts Ningishzida is said to be female, which means “Nin” would then refer to Lady, which is mostly how the word is used by the Sumerians. He or she was one of the ancestors of Gilgamesh.

Ningishzida is the earliest known symbol of snakes twining around an axial rod. It predates the Caduceus of Hermes, the Rod of Asclepius and the staff of Moses by more than a millennium. One Greek myth of origin of the caduceus is part of the story of Tiresias, who found two snakes copulating and killed the female with his staff.

Ares

Ares is the Greek god of war. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. In Greek literature, he often represents the physical or violent and untamed aspect of war, in contrast to the armored Athena, whose functions as a goddess of intelligence include military strategy and generalship.

The counterpart of Ares among the Roman gods is Mars, who as a father of the Roman people was given a more important and dignified place in ancient Roman religion as a guardian deity.

The etymology of the name Ares is traditionally connected with the Greek word arē, the Ionic form of the Doric ara, “bane, ruin, curse, imprecation”. There may also be a connection with the Roman god of war Mars, via hypothetical Proto-Indo-European *M̥rēs; compare Ancient Greek marnamai, “I fight, I battle”.

Walter Burkert notes that “Ares is apparently an ancient abstract noun meaning throng of battle, war.” R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name. The earliest attested form of the name is the Mycenaean Greek a-re, written in the Linear B syllabic script.

The adjectival epithet, Areios, was frequently appended to the names of other gods when they took on a warrior aspect or became involved in warfare: Zeus Areios, Athena Areia, even Aphrodite Areia. In the Iliad, the word ares is used as a common noun synonymous with “battle.”

Eris, the Greek goddess of chaos, strife and discord, or Enyo, the goddess of war, bloodshed, and violence, was considered the sister and companion of the violent Ares. In at least one tradition, Enyalius, rather than another name for Ares, was his son by Enyo.

Enyalius or Enyalio in Greek mythology is generally a byname of Ares the god of war but in Mycenaean times is differentiated as a separate deity. On the Mycenaean Greek Linear B KN V 52 tablet, the name, e-nu-wa-ri-jo, has been interpreted to refer to this same Enyalios.

The union of Ares and Aphrodite created the gods Eros, Anteros, Phobos, Deimos, Harmonia, and Adrestia. While Eros and Anteros’ godly stations favored their mother, Adrestia preferred to emulate her father, often accompanying him to war. Other versions include Alcippe as one of his daughters.

Alala

Allatu (Allatum) is an underworld goddess modeled after the mesopotamic goddess Ereshkigal and worshipped by western Semitic peoples, including the Carthaginians. She also may be equates with the Canaanite goddess Arsay. Alala, (Ancient Greek: “battle-cry” or “war-cry”), was the female personification of the war cry in Greek mythology. She was an attendant of the war god Ares, whose war cry was her name, “Alale alala”. Alalaxios is an epithet of Ares.

Allāt or al-Lāt was a Pre-Islamic Arabian goddess who was one of the three chief goddesses of Mecca. She is mentioned in the Qur’an (Sura 53:19), which indicates that pre-Islamic Arabs considered her as one of the daughters of Allah, along with Manāt and al-‘Uzzá.

Especially in older sources, Allat is an alternative name of the Mesopotamian goddess of the underworld, now usually known as Ereshkigal. She was reportedly also venerated in Carthage under the name Allatu.

The goddess occurs in early Safaitic graffiti (Safaitic han-‘Ilāt “the Goddess”). The Nabataeans of Petra and the people of Hatra also worshipped her, equating her with the Greek Athena and Tyche and the Roman Minerva.

She is frequently called “the Great Goddess” in Greek in multi-lingual inscriptions. According to Wellhausen, the Nabataeans believed al-Lāt was the mother of Hubal (and hence the mother-in-law of Manāt).

The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, considered her the equivalent of Aphrodite: The Assyrians call Aphrodite Mylitta, the Arabians Alilat and the Persians Mithra. In addition that deity is associated with the Indian deity Mitra.

This passage is linguistically significant as the first clear attestation of an Arabic word, with the diagnostically Arabic article al-. The Persian and Indian deities were developed from the Proto-Indo-Iranian deity known as *Mitra.

According to Herodotus, the ancient Arabians believed in only two gods: They believe in no other gods except Dionysus and the Heavenly Aphrodite; and they say that they wear their hair as Dionysus does his, cutting it round the head and shaving the temples. They call Dionysus, Orotalt; and Aphrodite, Alilat.

According to the 5th century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, Orotalt was a god of Pre-Islamic Arabia whom he identified with Dionysus. Also known as Đū Shará or Dusares (which means “Possessor of the (Mountain) Shara”), Orotalt was worshipped by the Nabataeans, Arabs who inhabited southern Jordan, Canaan and the northern part of Arabia.

Dushara (Arabic: “Lord of the Mountain”), also transliterated as Dusares, a deity in the ancient Middle East worshipped by the Nabataeans at Petra and Madain Saleh (of which city he was the patron).

He was mothered by Manat the goddess of fate. In Greek times, he was associated with Zeus because he was the chief of the Nabataean pantheon as well as with Dionysus. His sanctuary at Petra contained a great temple in which a large cubical stone was the centrepiece.

A shrine to Dushara has been discovered in the harbour of Pozzuoli in Italy. Ancient Puteoli was an important harbour for trade to the Near East, and a Nabataean presence is detected there in the mid 1st century BC.

The cult continued in some capacity well into the Roman period and possibly as late as the Islamic period. This deity was mentioned by the 9th century CE Muslim historian Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi, who wrote in The Book of Idols (Kitab al-Asnām) that: “The Banū al-Hārith ibn-Yashkur ibn-Mubashshir of the ʻAzd had an idol called Dū Sharā.”

Chaabou is one of the goddesses in the Nabataean pantheon, as noted by Epiphanius of Salamis (c.315–403). The description points to either Allat or Uzza, but is most likely the former, since Allat is also associated with Aphrodite, a fertility goddess.

According to Epiphanius, Chaabou was a virgin who gave birth to Dusares (aka Dhu Sharaa, and DVSARI), the ‘Lord of Mount Seir’, the god of the Nabataeans who was equated with Zeus.

Epiphanius records a festival celebrating the birth of Dusares on the 25th of December whereby the Black Stone of Dusares (considered newly born) is carried around the courtyard of the temple seven times.

Gerra

Gibil in Sumerian mythology is the god of fire, variously of the son of An and Ki, An and Shala or of Ishkur and Shala. He later developed into the Akkadian god Gerra (also known as Girra), the Babylonian and Akkadian god of fire. Gerra is the son of Anu and Antu. Guerra is a Portuguese, Spanish and Italian term meaning “war”.

Erra or Irra is an Akkadian plague god known from an ‘epos’ of the eighth century BCE. Erra is the god of mayhem and pestilence who is responsible for periods of political confusion. In the epic that is given the modern title Erra, the writer Kabti-ilani-Marduk, a descendant, he says, of Dabibi, presents himself in a colophon following the text as simply the transcriber of a visionary dream in which Erra himself revealed the text.

Uranus

Uranus (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. In Ancient Greek literature, Uranus or Father Sky was the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Uranus was conceived by Gaia alone, but other sources cite Aether as his father.

Uranus and Gaia were the parents of the first generation of Titans, and the ancestors of most of the Greek gods, but no cult addressed directly to Uranus survived into Classical times, and Uranus does not appear among the usual themes of Greek painted pottery. Elemental Earth, Sky and Styx might be joined, however, in a solemn invocation in Homeric epic.

The most probable etymology is from the basic Proto-Greek form worsanos derived from the noun worso-, Sanskrit: varsa “rain”. The relative Proto-Indo-European language root is *ṷers- “to moisten, to drip” (Sanskrit: varsati “to rain”), which is connected with the Greek ουρόω (Latin: “urina”, English: “urine”, compare Sanskrit: var “water,” Avestan var “rain”, Lithuanian & Latvian jura “sea”, Old English wær “sea,” Old Norse ver “sea,” Old Norse ur “drizzling rain”) therefore Ouranos is the “rainmaker” or the “fertilizer”.

Another possible etymology is “the one standing high in order” (Sanskrit: vars-man: height, Lithuanian: virus: upper, highest seat). The identification with the Vedic Varuna, god of the sky and waters, is uncertain. It is also possible that the name is derived from the PIE root *wel “to cover, enclose” (Varuna, Veles). or *wer “to cover, shut”.

Varuna

It is possible that Uranus was originally an Indo-European god, to be identified with the Vedic Váruṇa, the supreme keeper of order who later became the god of oceans and rivers, as suggested by Georges Dumézil, following hints in Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912).

Another of Dumézil’s theories is that the Iranian supreme God Ahura Mazda is a development of the Indo-Iranian *vouruna-*mitra. Therefore this divinity has also the qualities of Mitra, which is the god of the falling rain.

Uranus is connected with the night sky, and Váruṇa is the god of the sky and the celestial ocean, which is connected with the Milky Way. His daughter Lakshmi is said to have arisen from an ocean of milk, a myth similar to the myth of Aphrodite.

Georges Dumézil made a cautious case for the identity of Uranus and Vedic Váruṇa at the earliest Indo-European cultural level. Dumézil’s identification of mythic elements shared by the two figures, relying to a great extent on linguistic interpretation, but not positing a common origin, was taken up by Robert Graves and others.

The identification of the name Ouranos with the Hindu Váruṇa, based in part on a posited PIE root *-ŭer with a sense of “binding”—ancient king god Váruṇa binds the wicked, ancient king god Uranus binds the Cyclopes—is widely rejected by those who find the most probable etymology is from Proto-Greek *(F)orsanόj (worsanos) from a PIE root *ers “to moisten, to drip” (referring to the rain).

Vedic Indra is linked with Zeus grandson of Uranus, but according to Vedic myths Indra & Váruna were brothers so it is possible that Indra is the grand-uncle of Zeus and not his counterpart.

In Vedic religion, Varuna (Malay: Baruna) or Waruna, is a god of the water and of the celestial ocean, as well as a god of law of the underwater world. A Makara is his mount. In Hindu mythology, Varuna continued to be considered the god of all forms of the water element, particularly the oceans.

As chief of the Adityas, Varuna has aspects of a solar deity though, when opposed to Mitra (Vedic term for Surya), he is rather associated with the night and Mitra with the daylight. As the most prominent Deva, however, he is mostly concerned with moral and societal affairs than being a deification of nature.

Together with Mitra, originally ‘agreement’ (between tribes) personified, he is the supreme keeper of order and god of the law. Varuna and Mitra are the gods of the societal affairs including the oath, and are often twinned Mitra-Varuna (a dvandva compound). Varuna is also twinned with Indra in the Rigveda, as Indra-Varuna (when both cooperate at New Year in re-establishing order).

The Rigveda and Atharvaveda portray Varuna as omniscient, catching liars in his snares. The stars are his thousand-eyed spies, watching every movement of men.

In the Rigveda, Indra, chief of the Devas, is about six times more prominent than Varuna, who is mentioned 341 times. This may misrepresent the actual importance of Varuna in early Vedic society due to the focus of the Rigveda on fire and Soma ritual, Soma being closely associated with Indra; Varuna with his omniscience and omnipotence in the affairs of men has many aspects of a supreme deity.

The daily Sandhyavandanam ritual of a dvija addresses Varuna in this aspect in its evening routine, asking him to forgive all sins, while Indra receives no mention.

Both Mitra and Varuna are classified as Asuras in the Rigveda (e.g. RV 5.63.3), although they are also addressed as Devas as well (e.g. RV 7.60.12), possibly indicating the beginning of the negative connotations carried by Asura in later times.

In post-Vedic texts Varuna became the god of oceans and rivers and keeper of the souls of the drowned. As such, Varuna is also a god of the dead, and can grant immortality. He is attended by the nagas, the Sanskrit and Pāli word for a deity or class of entity or being, taking the form of a very great snake—specifically the king cobra, found in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. He is also one of the Guardians of the directions, representing the west.

Assuming that Vedic Varuna is not a purely Indian development (i.e. assuming that he derives from an Indo-Iranian *vouruna), there are several different theories on what might have happened to Indo-Iranian *vouruna in Iran.

Nyberg (Die Religionen des alten Iran, 1938:282ff) sees Varuna represented as the Amesha Spenta Asha Vahishta “Best Righteousness”, an opinion—with extensions—that Dumezil (Tarpeia 1947:33-113) and Widengren (Die Religionen Irans, 1965:12-13) also follow. This theory is based on Vedic Varuna’s role as the principal protector of rta, which in Iran is represented by asha [vahishta].

Kuiper (IIJ I, 1957) proposes that none less than Ahura Mazda is a development from an earlier dvandva *vouruna-mitra. The basis of Kuiper’s proposal is that the equivalent of Avestan mazda “wisdom” is Vedic medhira, described in Rigveda 8.6.10 as the “(revealed) insight into the cosmic order” that Varuna grants his devotees. In Kuiper’s view, Ahura Mazda is then a compound divinity in which the propitious characteristics of *mitra negate the unfavorable qualities of *vouruna.

Rta

Mitra is being master of ṛtá (ṛtaṃ), “that which is properly joined; order, rule; truth”), the principle of natural order which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it

The word ṛtá, order, is also translated as “season”. Ṛta is derived from the Sanskrit verb root ṛ- “to go, move, rise, tend upwards”, and the derivative noun ṛtam is defined as “fixed or settled order, rule, divine law or truth”.

As Mahony (1998) notes, however, the term can just as easily be translated literally as “that which has moved in a fitting manner”, abstractly as “universal law” or “cosmic order”, or simply as “truth”. The latter meaning dominates in the Avestan cognate to Ṛta, aša.

The notion of a universal principle of natural order is by no means unique to the Vedas, and Ṛta has been compared to similar ideas in other cultures, such as Ma’at in Ancient Egyptian religion, Moira and the Logos in Greek paganism, and the Tao.

In the hymns of the Vedas, Ṛta is described as that which is ultimately responsible for the proper functioning of the natural, moral and sacrificial orders. Conceptually, it is closely allied to the injunctions and ordinances thought to uphold it, collectively referred to as Dharma, and the action of the individual in relation to those ordinances, referred to as Karma – two terms which eventually eclipsed Ṛta in importance as signifying natural, religious and moral order in later Hinduism.

Sanskrit scholar Maurice Bloomfield referred to Ṛta as “one of the most important religious conceptions of the Rig Veda”, going on to note that, “from the point of view of the history of religious ideas we may, in fact we must, begin the history of Hindu religion at least with the history of this conception”.

Makara

Later art depicts Varuna as a lunar deity, as a yellow man wearing golden armor and holding a noose or lasso made from a snake. He rides the sea creature Makara, generally depicted as half terrestrial animal in the frontal part, in animal forms of an elephant, crocodile, stag, or deer, and in the hind part as an aquatic animal, in the form of a fish or seal tail. Sometimes, even a peacock tail is depicted.

Makara is the vahana (vehicle) of the Ganga – the goddess of river Ganges (Ganga) and the sea god Varuna. It is also the insignia of the love god Kamadeva, also known as Makaradhvaja (one whose flag a makara is depicted). Makara is the astrological sign of Capricorn, one of the twelve symbols of the Zodiac. It is often portrayed protecting entryways to Hindu and Buddhist temples.

Makara symbolized in ornaments are also in popular use as wedding gifts for bridal decoration. The Hindu Preserver-god Vishnu is also shown wearing makara-shaped earrings called Makarakundalas. The Sun god Surya and the Mother Goddess Chandi are also sometimes described as being adorned with Makarakundalas.

Caelus

The equivalent of Uranus in Roman mythology was Caelus or Coelus, a primal god of the sky in Roman myth and theology, iconography, and literature (compare caelum, the Latin word for “sky” or “the heavens”, hence English “celestial”).

The deity’s name usually appears in masculine grammatical form when he is conceived of as a male generative force, but the neuter form Caelum is also found as a divine personification.

The name of Caelus indicates that he was the Roman counterpart of the Greek god Uranus. Varro couples him with Terra (Earth) as pater and mater (father and mother), and says that they are “great deities” (dei magni) in the theology of the mysteries at Samothrace.

Although Caelus is not known to have had a cult at Rome, not all scholars consider him a Greek import given a Latin name; he has been associated with Summanus, the god of nocturnal thunder, as counterposed to Jupiter, the god of diurnal (daylight) thunder.

Caelus begins to appear regularly in Augustan art and in connection with the cult of Mithras during the Imperial era. Vitruvius includes him among celestial gods whose temple-buildings (aedes) should be built open to the sky.

The name Caelus occurs in dedicatory inscriptions in connection to the cult of Mithras. The Mithraic deity Caelus is sometimes depicted allegorically as an eagle bending over the sphere of heaven marked with symbols of the planets or the zodiac.

In a Mithraic context he is associated with Cautes, torch-bearers depicted attending the god Mithras in the icons of ancient Roman cult of Mithraism, known as Tauroctony, and can appear as Caelus Aeternus (“Eternal Sky”).

A form of Ahura-Mazda is invoked in Latin as Caelus Aeternus Iupiter. The walls of some mithrea feature allegorical depictions of the cosmos with Oceanus, s a pseudo-geographical feature in classical antiquity, believed by the ancient Greeks and Romans to be the divine personification of the World Ocean, an enormous river encircling the world, and Caelus.

The mithraeum, a place of worship for the followers of the mystery religion of Mithraism, of Dieburg represents the tripartite world with Caelus, Oceanus, and Tellus below Phaeton-Heliodromus.

According to Cicero and Hyginus, Caelus was the son of Aether and Dies (“Day” or “Daylight”). Caelus and Dies were in this tradition the parents of Mercury. With Trivia, Caelus was the father of the Roman god Janus, as well as of Saturn and Ops.

Caelus was also the father of one of the three forms of Jupiter, the other two fathers being Aether and Saturn. In one tradition, Caelus was the father with Tellus of the Muses, though was this probably a mere translation of Ouranos from a Greek source.

Caelus substituted for Uranus in Latin versions of the myth of Saturn (Cronus) castrating his heavenly father, from whose severed genitals, cast upon the sea, the goddess Venus (Aphrodite) was born.

In his work On the Nature of the Gods, Cicero presents a Stoic allegory of the myth in which the castration signifies “that the highest heavenly aether, that seed-fire which generates all things, did not require the equivalent of human genitals to proceed in its generative work.”

For Macrobius, the severing marks off Chaos from fixed and measured Time (Saturn/Cronus) as determined by the revolving Heavens (Caelum). The semina rerum (“seeds” of things that exist physically) come from Caelum and are the elements which create the world.

The divine spatial abstraction Caelum is a synonym for Olympus as a metaphorical heavenly abode of the divine, both identified with and distinguished from the mountain in ancient Greece named as the home of the gods.

Varro says that the Greeks call Caelum (or Caelus) “Olympus.” As a representation of space, Caelum is one of the components of the mundus, the “world” or cosmos, along with terra (earth), mare (sea), and aer (air).

In his work on the cosmological systems of antiquity, the Dutch Renaissance humanist Gerardus Vossius deals extensively with Caelus and his duality as both a god and a place that the other gods inhabit.

The ante-Nicene Christian writer Lactantius routinely uses the Latin theonyms Caelus, Saturn, and Jupiter to refer to the three divine hypostases of the Neoplatonic school of Plotinus: the First God (Caelus), Intellect (Saturn), and Soul, son of the Intelligible (Jupiter).

It is generally though not universally agreed that Caelus is depicted on the cuirass of the Augustus of Prima Porta, at the very top above the four horses of the Sun god’s quadriga. He is a mature, bearded man who holds a cloak over his head so that it billows in the form of an arch, a conventional sign of deity (velificatio) that “recalls the vault of the firmament.”

He is balanced and paired with the personification of Earth at the bottom of the cuirass. (These two figures have also been identified as Saturn and the Magna Mater, to represent the new Saturnian “Golden Age” of Augustan ideology.) On an altar of the Lares now held by the Vatican, Caelus in his chariot appears along with Apollo-Sol above the figure of Augustus.

As Caelus Nocturnus, he was the god of the night-time, starry sky. In a passage from Plautus, Nocturnus is regarded as the opposite of Sol, the Sun god. Nocturnus appears in several inscriptions found in Dalmatia and Italy, in the company of other deities who are found also in the cosmological schema of Martianus Capella, based on the Etruscan tradition.

In the Etruscan discipline of divination, Caelus Nocturnus was placed in the sunless north opposite Sol to represent the polar extremities of the axis. This alignment was fundamental to the drawing of a templum (sacred space) for the practice of augury.

YAWHE

Some Roman writers used Caelus or Caelum as a way to express the monotheistic god of Judaism. Juvenal identifies the Jewish god with Caelus as the highest heaven (summum caelum), saying that Jews worship the numen of Caelus; Petronius uses similar language.

Florus has a rather odd passage describing the Holy of Holies in the Temple of Jerusalem as housing a “sky” (caelum) under a golden vine, which has been taken as an uncomprehending attempt to grasp the presence of the Jewish god.

A golden vine, perhaps the one mentioned, was sent by the Hasmonean king Aristobulus to Pompeius Magnus after his defeat of Jerusalem, and was later displayed in the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.

Summanus and Fidus

Georges Dumézil has argued that Summanus would represent the uncanny, violent and awe-inspiring element of the gods of the first function, connected to heavenly sovereignty.

The double aspect of heavenly sovereign power would be reflected in the dichotomy Varuna-Mitra in Vedic religion and in Rome in the dichotomy Summanus-Dius Fidius, a god of oaths associated with Jupiter.

The first gods of these pairs would incarnate the violent, nocturnal, mysterious aspect of sovereignty while the second ones would reflect its reassuring, daylight and legalistic aspect.

Fidius may be an earlier form for filius, “son”, with the name Dius Fidius originally referring to Hercules as a son of Jupiter. According to some writers, the phrase medius fidius was equivalent to mehercule “My Hercules!”, a common interjection.

His name was thought to be related to Fides, the goddess of trust. Her temple on the Capitol was where the Roman Senate signed and kept state treaties with foreign countries, and where Fides protected them.

Jupiter

As a sky god, Caelus became identified with Jupiter (Latin: Iuppiter; genitive case: Iovis) or Jove, as indicated by an inscription that reads Optimus Maximus Caelus Aeternus Iup<pi>ter.

Jupiter is the king of the gods and the god of sky and thunder in myth. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire.

Jupiter is usually thought to have originated as a sky god. His identifying implement is the thunderbolt, and his primary sacred animal is the eagle, which held precedence over other birds in the taking of auspices and became one of the most common symbols of the Roman army. The two emblems were often combined to represent the god in the form of an eagle holding in its claws a thunderbolt, frequently seen on Greek and Roman coins.

As the sky-god, he was a divine witness to oaths, the sacred trust on which justice and good government depend. Many of his functions were focused on the Capitoline (“Capitol Hill”), where the citadel was located. He was the chief deity of the early Capitoline Triad with Mars and Quirinus. In the later Capitoline Triad, he was the central guardian of the state with Juno and Minerva. His sacred tree was the oak.

The Romans regarded Jupiter as the equivalent of the Greek Zeus, and in Latin literature and Roman art, the myths and iconography of Zeus are adapted under the name Iuppiter.

In the Greek-influenced tradition, Jupiter was the brother of Neptune and Pluto. Each presided over one of the three realms of the universe: sky, the waters, and the underworld. The Italic Diespiter was also a sky god who manifested himself in the daylight, usually but not always identified with Jupiter.

Tinia

Tinia, the god of the sky and the highest god in Etruscan mythology, equivalent to the Roman Jupiter and the Greek Zeus, is usually regarded as his Etruscan counterpart. He was the husband of Thalna or Uni and the father of Hercle. Tinia was also part of the powerful “trinity” that included Menrva and Uni and had temples in every city of Etruria.

Ani

Ani was the god of the sky who lived in the highest level of the heavens, and the god of passage. His female counterpart (similar person) was Ana. Ani was like the Etruscan version of the Latin god Janus, because he was similarly a two-faced god. His name may be linked to the Roman god Janus.

Janus

It has long been believed that Janus was present among the theonyms on the outer rim of the Piacenza Liver in case 3 under the name of Ani. This fact created a problem as the god of beginnings looked to be located in a situation other than the initial, i.e. the first case.

After the new readings proposed by A. Maggiani, in case 3 one should read TINS: the difficulty has thus dissolved. Ani has thence been eliminated from Etruscan theology as this was his only attestation. Maggiani remarks that this earlier identification was in contradiction with the testimony ascribed to Varro by Johannes Lydus that Janus was named caelum among the Etruscans.

The Piacenza liver is a striking conceptual parallel to clay models of sheep’s livers known from the Ancient Near East, reinforcing the evidence of a connection between the Etruscans and the Anatolian cultural sphere. A Babylonian clay model of a sheep’s liver dated to the Middle Bronze Age is preserved in the British Museum.

Culsans

Culsans was a two-headed Etruscan god of doorways, doors, and death, same as the two-faced Roman god Janus and Portunes of Roman Mythology, and in fact the Romans appropriated him via Interpretatio Romana. But there are, however, a few distinct differences, that would likely matter to an ancient Etruscan.

Culsans is, like many Etruscan deities, a god of the underworld, and thus may have other death-themed powers and responsibilities, Culsans’ two heads are always both presented as youthful, whereas the two heads of Janus are depicted as one youthful and one aged, and Culsans is often accompanied by his scissors-toting, bare-breasted companion Culsu.

Culsu

Culsu, also Cul, is an Etruscan goddess associated with gateways and death. She appears as a topless winged woman carrying a torch and scissors. Her name means “She Who Coils”. As with many Etruscan deities, she has wings, presides over death or the underworld, and has an unexplained association with snakes (“she who coils”).

Most of the Etruscan religion and mythology was lost long ago, along with their language and culture, so we don’t really know a lot about Culsu, but she is often referred to as a demon by scholars and in haruspicy (augury), she presides over certain ill omens.

She stood at the gates of the underworld, with her partner Culsans, and she was often painted next to Culsans, whom the Romans decided was also the figure they knew as Janus. The nature of their relationship is poorly understood, but they seem to possibly guard the gates of the underworld together.

Cel

Cel, also Cilens or Celens, named either Ati Cel (“Father Earth”) or Apa Cel (“Mother Earth”), was an Etruscan Earth god. On the Etruscan calendar, the month of Celi (September) is likely named for her. Her Greek counterpart is Gaia and her Roman is Tellus. Cel appears on the Liver of Piacenza, a bronze model of a liver marked for the Etruscan practice of haruspicy. She is placed in House 13.

In Etruscan mythology, Cel was the mother of the Giants. In Greek, “giant” comes from a word meaning “born from Gaia.” A bronze mirror from the 5th century BC depicts a theomachy in which Celsclan, “son of Cel,” is a Giant attacked by Laran, the god of war. Another mirror depicts anguiped Giants in the company of a goddess, possibly Cel, whose lower body is formed of vegetation.

In a sanctuary near Lake Trasimeno were found five votive bronze statuettes, some male and some female, dedicated to her as Cel Ati, “Mother Cel.” The inscription on each reads mi celś atial celthi, “I [belong to, have been given] to Cel the mother, here [in this sanctuary].”

Hel

In Norse mythology, Hel is a being who presides over a realm of the same name, where she receives a portion of the dead. Scholarly theories have been proposed about Hel’s potential connections to figures appearing in the 11th century Old English Gospel of Nicodemus and Old Norse Bartholomeus saga postola, potential Indo-European parallels to Bhavani, Kali, and Mahakali, and her origins.

In Norse mythology, Hel (Old Norse Hel, “Hidden”, from the word hel, “to conceal”), also known as Hella, Holle or Hulda, is a giantess and goddess in Norse mythology who rules over Helheim, the underworld where the dead dwell, which was known as Niflheim, or Helheim, the Kingdom of the Dead. The name Hel, quite literally means “one that hides” or “one who covers up.”

Hel was the daughter of Loki and a giantess. Her siblings are the wolf Fenrir and the snake Jormungand. She was half alive, half dead. Half of her face is beautiful, reminiscent of her father, while the other half is ugly and difficult to look at like her mother. She is described as half white/half blue, or half living/half rotten.

The old Old Norse word Hel derives from Proto-Germanic *khalija/*haljō, which means “one who covers up or hides something”, which itself derives from Proto-Indo-European *kel-, meaning “conceal”.

The cognate in English is the word Hell which is from the Old English forms hel and helle. Related terms are Old Frisian, helle, German Hölle and Gothic halja. Other words more distantly related include hole, hollow, hall, helmet and cell, all from the aforementioned Indo-European root *kel-.

The word Hel is found in Norse words and phrases related to death such as Helför (“Hel-journey,” a funeral) and Helsótt (“Hel-sickness,” a fatal illness). The Norwegian word “heilag/hellig” which means “sacred” is directly related etymologically to the name “Hel”, and the same goes for the English word “holy”.

Both Hel and Heimdallr are strongly connected to the rune Haglaz or Hagalaz (Hag-all-az) – literally: “Hail” or “Hailstone” – Esoteric: Crisis or Radical Change. Interesting enough to notice that “heil” is also a name of this rune when it has a protection aspect, as heil/heilag comes from Hel, and the word “heil” was also found in the “Heil og Sæl” (an old norse way to greet which means “to good health and happiness”).

The reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of the h-rune ᚺ, meaning “Hag-all-az” – Literally: “Hail” or “Hailstone”. In the Anglo-Saxon futhorc, it is continued as hægl and in the Younger Futhark as ᚼ hagall. The corresponding Gothic letter is h, named hagl.

Hail is a form of solid precipitation. It is distinct from sleet, though the two are often confused for one another It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailstone. Sleet falls generally in cold weather while hail growth is greatly inhibited at cold temperatures.

Hail shocks you with stinging hardness (confrontation) then it melts into water which creates germination of seeds (transformation). The ancients describe hail as a grain rather than as ice, thus creating a metaphor for a deeper truth of life. It contains the seed of all the other runic energies and this can be seen in its other form, a six-fold snowflake. Spiritual awakening often comes from times of deep crisis.

Celts

The ethnonym Celts probably stems from the Indo-European root *kel- or *(s)kel-, but there are several such roots of various meanings: *kel- “to be prominent”, *kel- “to drive or set in motion”, *kel- “to strike or cut”, etc.

Khaldi/ Theispas

Ḫaldi (Ḫaldi, also known as Khaldi or Hayk) was one of the three chief deities of Ararat (Urartu). His shrine was at Ardini. Of all the gods of Ararat (Urartu) pantheon, the most inscriptions are dedicated to him. His wife was the goddess Arubani. He is portrayed as a man with or without a beard, standing on a lion.

Khaldi was a warrior god whom the kings of Urartu would pray to for victories in battle. The temples dedicated to Khaldi were adorned with weapons, such as swords, spears, bow and arrows, and shields hung off the walls and were sometimes known as ‘the house of weapons’.

Hayk or Hayg, also known as Haik Nahapet (Hayk the Tribal Chief) is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation. His story is told in the History of Armenia attributed to the Armenian historian Moses of Chorene (410 to 490).

Hayasa-Azzi or Azzi-Hayasa was a Late Bronze Age confederation formed between two kingdoms of Armenian Highlands, Hayasa located South of Trabzon and Azzi, located north of the Euphrates and to the south of Hayasa. The Hayasa-Azzi confederation was in conflict with the Hittite Empire in the 14th century BC, leading up to the collapse of Hatti around 1190 BC.

The similarity of the name Hayasa to the endonym of the Armenians, Hayk or Hay and the Armenian name for Armenia, Hayastan has prompted the suggestion that the Hayasa-Azzi confereration was involved in the Armenian ethnogenesis.

Thus, the Great Soviet Encyclopedia of 1962 posited that the Armenians derive from a migration of Hayasa into Shupria in the 12th century BC. This is open to objection due to the possibility of a mere coincidental similarity between the two names and the lack of geographic overlap, although Hayasa (the region) became known as Lesser Armenia (Pokr Hayastan in modern Armenian) in coming centuries.

The term Hayastan bears resemblance to the ancient Mesopotamian god Haya (ha-ià) and another western deity called Ebla Hayya, related to the god Ea (Enki or Enkil in Sumerian, Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian).

Haya’s functions are two-fold: he appears to have served as a door-keeper but was also associated with the scribal arts, and may have had an association with grain. He is the spouse of Nidaba/Nissaba, the Sumerian goddess of grain and writing, patron deity of the city Ereš (Uruk).

There is also a divine name Haia(-)amma in a bilingual Hattic-Hittite text from Anatolia which is used as an equivalent for the Hattic grain-goddess Kait in an invocation to the Hittite grain-god Halki, although it is unclear whether this appellation can be related to ha-ià.

In some cases he was identified as father of the goddess Ninlil, a goddess mainly known as the wife of Enlil, and later of Aššur, the head of the Assyrian pantheon. Ninlil first appears in the late fourth millennium BCE and survived into the first centuries CE. She was at times syncretised with various healing and mother goddesses as well as with the goddess Inanna (Ninana)/Ištar.

Haya is also characterised, beyond being the spouse of Nidaba/Nissaba, as an “agrig”-official of the god Enlil. The god-list AN = Anu ša amēli (lines 97-98) designates him as “the Nissaba of wealth”, as opposed to his wife, who is the “Nissaba of Wisdom”.

Traditions vary regarding the genealogy of Nidaba. She appears on separate occasions as the daughter of Enlil, of Uraš, of (Enki) Ea, and of Anu. Together Haya and Nidaba have a daughter called Sud/Ninlil. Two myths describe the marriage of Sud/Ninlil with Enlil. This implies that Nidaba could be at once the daughter and the mother-in-law of Enlil. Nidaba is also the sister of Ninsumun, the mother of Gilgameš.

Nidaba is frequently mentioned together with the goddess Nanibgal who also appears as an epithet of Nidaba, although most god lists treat her as a distinct goddess. In a debate between Nidaba and Grain, Nidaba is syncretised with Ereškigal as “Mistress of the Underworld”. Nidaba is also identified with the goddess of grain Ašnan, and with Nanibgal/Nidaba-ursag/Geme-Dukuga, the throne bearer of Ninlil and wife of Ennugi, throne bearer of Enlil.

Theispas, also sometimes the god of war, is a counterpart to the Assyrian god Adad, and the Hurrian god, Teshub. He was often depicted as a man standing on a bull, holding a handful of thunderbolts. His wife was the goddess Huba, who was the counterpart of the Hurrian goddess Hebat.

The other two chief deities were the Urartian weather-god Theispas (also known as Teisheba or Teišeba) of Kumenu, notably the god of storms and thunder, and the solar god Shivini or Artinis (the present form of the name is Artin, meaning “sun rising” or to “awake”, and it persists in Armenian names to this day) of Tushpa.

An, Kumarbi and Teshup

The Greek creation myth is similar to the Hurrian creation myth. In Hurrian religion Anu is the sky god. His son Kumarbi, the chief god of the Hurrians, bit off his genitals and spat out three deities, one of whom, Teshub (also written Teshup or Tešup; cuneiform IM), the Hurrian god of sky and storm, later deposed Kumarbis. In Sumerian mythology and later for Assyrians and Babylonians, Anu is the sky god and represented law and order.

Kumarbi was identified by the Hurrians with Sumerian Enlil, and by the Ugaritians with El, while Teshub is related to the Hattian Taru. His Hittite and Luwian name was Tarhun (with variant stem forms Tarhunt, Tarhuwant, Tarhunta), although this name is from the Hittite root *tarh- “to defeat, conquer”.

Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

The Hurrian myth of Teshub’s origin—he was conceived when the god Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his father Anu’s genitals, as such it most likely shares a Proto-Indo-European cognate with the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony. Teshub’s brothers are Aranzah (personification of the river Tigris), Ullikummi (stone giant) and Tashmishu.

In the Hurrian schema, Teshub was paired with Hebat the mother goddess; in the Hittite, with the sun goddess Arinniti of Arinna—a cultus of great antiquity which has similarities with the venerated bulls and mothers at Çatalhöyük in the Neolithic era. His son was called Sarruma, the mountain god.

Anshar and Kishar

In the Babylonian creation myth Enuma Elish, Anshar (also spelled Anshur), which means “sky pivot” or “sky axle”, is a sky god. He is the husband of his sister Kishar. They might both represent heaven (an), the male principle, and earth (ki), the female principle.

Both are the second generation of gods; their parents being the serpents Lahmu and Lahamu and grandparents Tiamat and Abzu. They, in turn, are the parents of Anu, another sky god.

During the reign of Sargon II, Assyrians started to identify Anshar with their Assur in order to let him star in their version of Enuma Elish. In this mythology Anshar’s spouse was Ninlil, “lady of the open field” or “Lady of the Wind”, also called Sud, in Assyrian called Mulliltu, in Sumerian mythology the consort goddess of Enlil.

The parentage of Ninlil is variously described. Most commonly she is called the daughter of Haia (god of stores) and Nunbarsegunu (or Ninshebargunnu, a goddess of barley, or Nisaba).

Another Akkadian source says she is the daughter of Anu (aka An) and Antu (Sumerian Ki). Other sources call her a daughter of Anu and Nammu. Theophilus G. Pinches noted that Nnlil or Belit Ilani had seven different names (such as Nintud, Ninhursag, Ninmah, etc.) for seven different localities.

In Enuma Elish Anshar and Ninlil do evil, unspeakable things. Then, Abzu decides to try to destroy them. They both hear of the plan and kill him first. Tiamat gets outraged and gives birth to 11 children. They then kill them both and then are outmatched by anyone.

Marduk (God of rain/thunder/lightning) kills Tiamat by wrapping a net around her and summoning the 4 winds to make her swell, then Marduk shoots an arrow into her and kills her. Half of her body is then divided to create the heavens and the Earth. He uses her tears to make rivers on Earth and take her blood to make humans.

If this name /Anšar/ is derived from */Anśar/, then it may be related to the Egyptian hieroglyphic /NṬR/ (“god”), since hieroglyphic Egyptian /Ṭ/ may be etymological */Ś/. Anšar might also be the same as Antum.

Asherah (Ugaritic: ‘ṯrt), in Semitic mythology, is a mother goddess who appears in a number of ancient sources. She appears in Akkadian writings by the name of Ashratum/Ashratu, and in Hittite as Asherdu(s) or Ashertu(s) or Aserdu(s) or Asertu(s). Asherah is generally considered identical with the Ugaritic goddess ʼAṯirat. The Ancient Greeks identified Hathor with the goddess Aphrodite, while in Roman mythology she corresponds to Venus.

In Egypt, beginning in the 18th dynasty, a Semitic goddess named Qudshu (‘Holiness’) begins to appear prominently, equated with the native Egyptian goddess Hathor. Some think this is Athirat/Ashratu under her Ugaritic name. If Asherah is to be associated with Hathor/Qudshu, it can then be assumed that the cow is what’s being referred to as Asherah.

Anu and Antu

In Akkadian mythology, Antu or Antum is a Babylonian goddess. She was the first consort of Anu, and the pair was the parents of the Anunnaki and the Utukki. Antu was a dominant feature of the Babylonian akit festival until as recently as 200 BC, her later pre-eminence possibly attributable to identification with the Greek goddess Hera. Antu was replaced as consort by Ishtar or Inanna, who may also be a daughter of Anu and Antu. She is similar to Anat.

Anu was a sky-god, the god of heaven, lord of constellations, king of gods, spirits and demons, and dwelt in the highest heavenly regions. It was believed that he had the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and that he had created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the royal tiara. His attendant and minister of state was the god Ilabrat.

The purely theoretical character of Anu is thus still further emphasized, and in the annals and votive inscriptions as well as in the incantations and hymns, he is rarely introduced as an active force to whom a personal appeal can be made. His name becomes little more than a synonym for the heavens in general and even his title as king or father of the gods has little of the personal element in it.

A consort Antum (or as some scholars prefer to read, Anatum) is assigned to him, on the theory that every deity must have a female associate. But Anu spent so much time on the ground protecting the Sumerians he left her in Heaven and then met Innin, whom he renamed Innan, or, “Queen of Heaven”. She was later known as Ishtar. Anu resided in her temple the most, and rarely went back up to Heaven. He is also included in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and is a major character in the clay tablets.

Anu is so prominently associated with the E-anna temple in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech) in southern Babylonia that there are good reasons for believing this place to be the original seat of the Anu cult. If this is correct, then the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar) of Uruk may at one time have been his consort.

Anu had several consorts, the foremost being Ki (earth), Nammu, and Uras. By Ki he was the father of, among others, the Anunnaki gods. By Uras he was the father of Nin’insinna.

According to legends, heaven and earth were once inseparable until An and Ki bore Enlil, god of the air, who cleaved heaven and earth in two. An and Ki were, in some texts, identified as brother and sister being the children of Anshar and Kishar. Ki later developed into the Akkadian goddess Antu (also known as “Keffen Anu”, “Kef”, and “Keffenk Anum”).

Anu existed in Sumerian cosmogony as a dome that covered the flat earth; Outside of this dome was the primordial body of water known as Tiamat (not to be confused with the subterranean Abzu).

In Sumerian, the designation “An” was used interchangeably with “the heavens” so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted.

The Akkadians inherited An as the god of heavens from the Sumerian as Anu-, and in Akkadian cuneiform, the DINGIR character may refer either to Anum or to the Akkadian word for god, ilu-, and consequently had two phonetic values an and il. Hittite cuneiform as adapted from the Old Assyrian kept the an value but abandoned il.

Anu, Enlil and Enki

Anu was one of the oldest gods in the Sumerian pantheon and part of a triad including Enlil (god of the air) and Enki (god of water). He was called Anu by the later Akkadians in Babylonian culture. By virtue of being the first figure in a triad consisting of Anu, Enlil, and Enki (also known as Ea), Anu came to be regarded as the father and at first, king of the gods.

The doctrine once established remained an inherent part of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion and led to the more or less complete disassociation of the three gods constituting the triad from their original local limitations.

An intermediate step between Anu viewed as the local deity of Uruk, Enlil as the god of Nippur, and Ea as the god of Eridu is represented by the prominence which each one of the centres associated with the three deities in question must have acquired, and which led to each one absorbing the qualities of other gods so as to give them a controlling position in an organized pantheon.

For Nippur we have the direct evidence that its chief deity, En-lil, was once regarded as the head of the Sumerian pantheon. The sanctity and, therefore, the importance of Eridu remained a fixed tradition in the minds of the people to the latest days, and analogy therefore justifies the conclusion that Anu was likewise worshipped in a centre which had acquired great prominence.

The summing-up of divine powers manifested in the universe in a threefold division represents an outcome of speculation in the schools attached to the temples of Babylonia, but the selection of Anu, Enlil (and later Marduk), and Ea for the three representatives of the three spheres recognized, is due to the importance which, for one reason or the other, the centres in which Anu, Enlil, and Ea were worshipped had acquired in the popular mind.

Each of the three must have been regarded in his centre as the most important member in a larger or smaller group, so that their union in a triad marks also the combination of the three distinctive pantheons into a harmonious whole.

In the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively.

Eridu (Nun-ki)

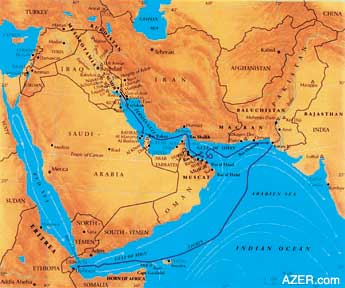

Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI; Sumerian: eriduki; Akkadian: irîtu) is an ancient Sumerian city in what is now Tell Abu Shahrain, Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq. Eridu was long considered the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia.

One name of Eridu in cuneiform logograms was pronounced “NUN.KI” (“the Mighty Place”) in Sumerian, but much later the same “NUN.KI” was understood to mean the city of Babylon. Eridu, also transliterated as Eridug, could mean “mighty place” or “guidance place”.

Located 12 km southwest of Ur, Eridu was the southernmost of a conglomeration of Sumerian cities that grew about temples, almost in sight of one another.

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu was originally the home of Enki, later known by the Akkadians as Ea, who was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem.

Like all the Sumerian and Babylonian gods, Enki/Ea began as a local god, who came to share, according to the later cosmology, with Anu and Enlil, the rule of the cosmos. His kingdom was the waters that surrounded the World and lay below it (Sumerian ab=water; zu=far).

In the Sumerian king list, Eridu is named as the city of the first kings. The king list gave particularly long rules to the kings who ruled before a great flood occurred, and shows how the center of power progressively moved from the south to the north of the country.

According to the king list: In Eridu, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28800 years. Alalngar ruled for 36000 years. 2 kings; they ruled for 64800 years. Then Eridu fell and the kingship was taken to Bad-tibira, “Wall of the Copper Worker(s)”, or “Fortress of the Smiths”, identified as modern Tell al-Madineh, between Ash Shatrah and Tell as-Senkereh (ancient Larsa) in southern Iraq.

Adapa, elsewhere called the first man, was a half-god, half-man culture hero, called by the title Abgallu (ab=water, gal=big, lu=man) of Eridu. He was considered to have brought civilization to the city from Dilmun, and he served Alulim.

The stories of Inanna, goddess of Uruk, describe how she had to go to Eridu in order to receive the gifts of civilization. At first Enki, the god of Eridu attempted to retrieve these sources of his power, but later willingly accepted that Uruk now was the centre of the land. This seems to be a mythical reference to the transfer of power northward, mentioned above.

Babylonian texts also talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, “the holy city, the dwelling of their [the other gods] delight”.

In the court of Assyria, special physicians trained in the ancient lore of Eridu, far to the south, foretold the course of sickness from signs and portents on the patient’s body, and offered the appropriate incantations and magical resources as cures.

The Egyptologist David Rohl has suggested that Eridu is the original site of Babel, and that the incomplete ziggurat found there – by far the oldest and largest of its kind – is none other than the remnants of the Biblical tower. Other scholars have discussed at length a number of additional correspondences between the names of “Babylon” and “Eridu”.

Rohl further equate Biblical Nimrod, said to have built Erech (Uruk) and Babel, with the name Enmerkar (-KAR meaning “hunter”) of the king-list and other legends, who is said to have built temples both in his capital of Uruk and in Eridu, and is even credited with the invention of writing on clay tablets, for the purpose of threatening Aratta into submission.

The king list adds that Enmerkar became king after his father Mesh-ki-ang-gasher, son of Utu, had “entered the sea and disappeared.” Enmerkar is also known from Sumerian legends, most notably Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, where a previous confusion of the languages of mankind is mentioned. In this account, it is Enmerkar himself who is called ‘the son of Utu’ (the Sumerian sun god).

Older accounts sometimes suppose that by reason of the constant accumulation of soil in the Euphrates valley Eridu was formerly situated on the Persian Gulf itself (as indicated by mention in Sumerian texts of its being on the Apsu), but it is now known that the opposite is true, that the waters of the Persian Gulf have been eroding the land and that the Apsu must refer to the fresh water of the marshes surrounding the city.

Tthe name of Marduk’s sanctuary at Babylon bears the same name, Esaggila, as that of Ea in Eridu. Marduk is generally termed the son of Ea, who derives his powers from the voluntary abdication of the father in favor of his son.

Enki

Enki was a deity in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Babylonian mythology. The name Ea is of Sumerian origin and was written by means of two signs signifying “house” and “water”. In the city Eridu the main temple to Enki is called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu.

Certain tanks of holy water in Babylonian and Assyrian temple courtyards were also called abzu (apsû). Typical in religious washing, these tanks were similar to the washing pools of Islamic mosques, or the baptismal font in Christian churches.

The Sumerian god Enki (Ea in the Akkadian language) was believed to live in the abzu since before human beings were created. His wife Damgalnuna, his mother Nammu, his advisor Isimud and a variety of subservient creatures, such as the gatekeeper Lahmu, also lived in the abzu.

The Abzu (Cuneiform: ZU.AB; Sumerian: abzu; Akkadian: apsû) also called engur, (Cuneiform: LAGAB×HAL; Sumerian: engur; Akkadian: engurru) literally, ab=’water’ (or ‘semen’) zu=’to know’ or ‘deep’ was the name for fresh water from underground aquifers that was given a religious fertilizing quality in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology. Lakes, springs, rivers, wells, and other sources of fresh water were thought to draw their water from the abzu.

Abzu (apsû) is depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Elish, taken from the library of Assurbanipal (c 630 BCE) but which is about 500 years older. In this story, he was a primal being made of fresh water and a lover to another primal deity, Tiamat, who was a creature of salt water.

The Enuma Elish begins: When above the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, the first, the begetter, and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, she who bore them all; they were still mixing their waters, and no pasture land had yet been formed, nor even a reed marsh…

The exact meaning of the name of Enki is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

He is the creater of the first man, Adamu or Adapa. He was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization, and he was regarded as the protector and teacher of mankind. He is essentially a god of civilization, and it was natural that he was also looked upon as the creator of man, and of the world in general.

His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus – the basis for the winged caduceus symbol used by modern Western medicine, the Rod of Asclepius, and the rod of Hermes. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

Enki was the deity of water, intelligence, creation, and lord of the Apsu, the watery abyss. Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water’”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

He was the leader of the first sons of Anu who came down to Earth, playing a pivotal role in creating humans then saving them from the Deluge. According to Sumerian mythology, Enki allowed humanity to survive the Deluge designed to kill them.

After Enlil and the rest of the Anunnaki, decided that Man would suffer total annihilation, he covertly rescued the human man Ziusudra by either instructing him to build some kind of an boat for his family, or by bringing him into the heavens in a magic boat. This is apparently the oldest surviving source of the Noah’s Ark myth and other parallel Middle Eastern Deluge myths.

Linked to flood myths, Enki was considered a god of life and replenishment, and was often depicted with streams of water emanating from his shoulders. Alongside him were trees symbolizing the male and female aspects of nature, each holding the male and female aspects of the ‘Life Essence’, which he, as apparent alchemist of the gods, would masterfully mix to create several beings that would live upon the face of the Earth.

His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. Enki’s sacred number is 40.

Nun

Nu (“watery one”), also called Nun (“inert one”) is the deification of the primordial watery abyss in Egyptian mythology. In the Ogdoad cosmogony, the word nu means “abyss”. In the Ennead cosmogony Nun is perceived as transcendent at the point of creation alongside Atum the creator god.

The Ancient Egyptians envisaged the oceanic abyss of the Nun as surrounding a bubble in which the sphere of life is encapsulated, representing the deepest mystery of their cosmogony.

In Ancient Egyptian creation accounts the original mound of land comes forth from the waters of the Nun. The Nun is the source of all that appears in a differentiated world, encompassing all aspects of divine and earthly existence.

Nu was shown usually as male but also had aspects that could be represented as female or male. Nunet (also spelt Naunet) is the female aspect, which is the name Nu with a female gender ending.

The male aspect, Nun, is written with a male gender ending. As with the primordial concepts of the Ogdoad, Nu’s male aspect was depicted as a frog, or a frog-headed man.

In Ancient Egyptian art, Nun also appears as a bearded man, with blue-green skin, representing water, while Naunet is represented as a snake or snake-headed woman.

Beginning with the Middle Kingdom Nun is described as “the Father of the Gods” and he is depicted on temple walls throughout the rest of Ancient Egyptian religious history.

The Ogdoad includes with Naunet and Nun, Amaunet and Amun, Hauhet and Heh, and Kauket with Kuk. Like the other Ogdoad deities, Nu did not have temples or any center of worship. Even so, Nu was sometimes represented by a sacred lake, or, as at Abydos, by an underground stream.

In the 12th Hour of the Book of Gates Nu is depicted with upraised arms holding a “solar bark” (or barque, a boat). The boat is occupied by eight deities, with the scarab deity Khepri standing in the middle surrounded by the seven other deities.

During the late period when Egypt became occupied the negative aspect of the Nun (chaos) became the dominant perception, reflecting the forces of disorder that were set loose in the country.

Atum

Atum, sometimes rendered as Atem or Tem, is an important deity in Egyptian mythology. His name is thought to be derived from the word tem which means to complete or finish. Thus he has been interpreted as being the ‘complete one’ and also the finisher of the world, which he returns to watery chaos at the end of the creative cycle.

He is usually depicted as a man wearing either the royal head-cloth or the dual white and red crown of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, reinforcing his connection with kingship. Sometimes he also is shown as a serpent, the form he returns to at the end of the creative cycle, and also occasionally as a mongoose, lion, bull, lizard, or ape.

As creator he was seen as the underlying substance of the world, the deities and all things being made of his flesh or alternatively being his ka, the Egyptian concept of vital essence, that which distinguishes the difference between a living and a dead person, with death occurring when the ka left the body.

The Egyptians believed that Khnum created the bodies of children on a potter’s wheel and inserted them into their mothers’ bodies. Depending on the region, Egyptians believed that Heket or Meskhenet was the creator of each person’s Ka, breathing it into them at the instant of their birth as the part of their soul that made them be alive. This resembles the concept of spirit in other religions.

The Egyptians also believed that the ka was sustained through food and drink. For this reason food and drink offerings were presented to the dead, although it was the kau within the offerings that was consumed, not the physical aspect. The ka was often represented in Egyptian iconography as a second image of the king, leading earlier works to attempt to translate ka as double.

Atum is one of the most important and frequently mentioned deities from earliest times, as evidenced by his prominence in the Pyramid Texts, where he is portrayed as both a creator and father to the king.

In the Heliopolitan creation myth, Atum was considered to be the first god, having created himself, sitting on a mound (benben) (or identified with the mound itself), from the primordial waters (Nu).

Early myths state that Atum created the god Shu and goddess Tefnut by spitting them out of his mouth. To explain how Atum did this, the myth uses the metaphor of masturbation, with the hand he used in this act representing the female principle inherent within him.

Atum was a self-created deity, the first being to emerge from the darkness and endless watery abyss that existed before creation. In the Book of the Dead, which was still current in the Graeco-Roman period, the sun god Atum is said to have ascended from chaos-waters with the appearance of a snake, the animal renewing it self every morning.

Atum is the god of pre-existence and post-existence. In the binary solar cycle, the serpentine Atum is contrasted with the ram-headed scarab Khepri – the young sun god, whose name is derived from the Egyptian hpr “to come into existence”. Khepri-Atum encompassed sunrise and sunset, thus reflecting the entire solar cycle.

Filed under:

Uncategorized ![]()

![]()