![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7d/Erebuni_pattern.jpg]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Yerevan (Erban – Urban)

Er/Ur/Ar – To create – Van/Ban – Home/Nest

-

Er/Ur/Ar – Urartu – Armenia

In Sumerian ![]() (URU) is written before the city name, often in combination with

(URU) is written before the city name, often in combination with ![]() (KI) after the city names. Cities are often indicated with their Sumerian names (Akkadian logograms): meaning: Sum. uru `city’, Akk. alu(m) `city’.

(KI) after the city names. Cities are often indicated with their Sumerian names (Akkadian logograms): meaning: Sum. uru `city’, Akk. alu(m) `city’.

![]()

![]()

![]() - urununki, Eridu, the city Eridu, home of the water god Ea.

- urununki, Eridu, the city Eridu, home of the water god Ea.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() – uru unug ki, Ur, the city Ur, important port in South Mesopotamia and home of the moon god Sîn.

– uru unug ki, Ur, the city Ur, important port in South Mesopotamia and home of the moon god Sîn.

![]()

![]()

Urbanization

Urbanization is the increasing number of people that migrate from rural to urban areas. It predominantly results in the physical growth of urban areas, be it horizontal or vertical. The United Nations projected that half of the world’s population would live in urban areas at the end of 2008. By 2050 it is predicted that 64.1% and 85.9% of the developing and developed world respectively will be urbanized.

Urbanization is closely linked to modernization, industrialization, and the sociological process of rationalization. Urbanization can describe a specific condition at a set time, i.e. the proportion of total population or area in cities or towns, or the term can describe the increase of this proportion over time. So the term urbanization can represent the level of urban development relative to overall population, or it can represent the rate at which the urban proportion is increasing.

Urbanization is not merely a modern phenomenon, but a rapid and historic transformation of human social roots on a global scale, whereby predominantly rural culture is being rapidly replaced by predominantly urban culture.

The last major change in settlement patterns was the accumulation of hunter-gatherers into villages many thousand years ago. Village culture is characterized by common bloodlines, intimate relationships, and communal behavior whereas urban culture is characterized by distant bloodlines, unfamiliar relations, and competitive behavior.

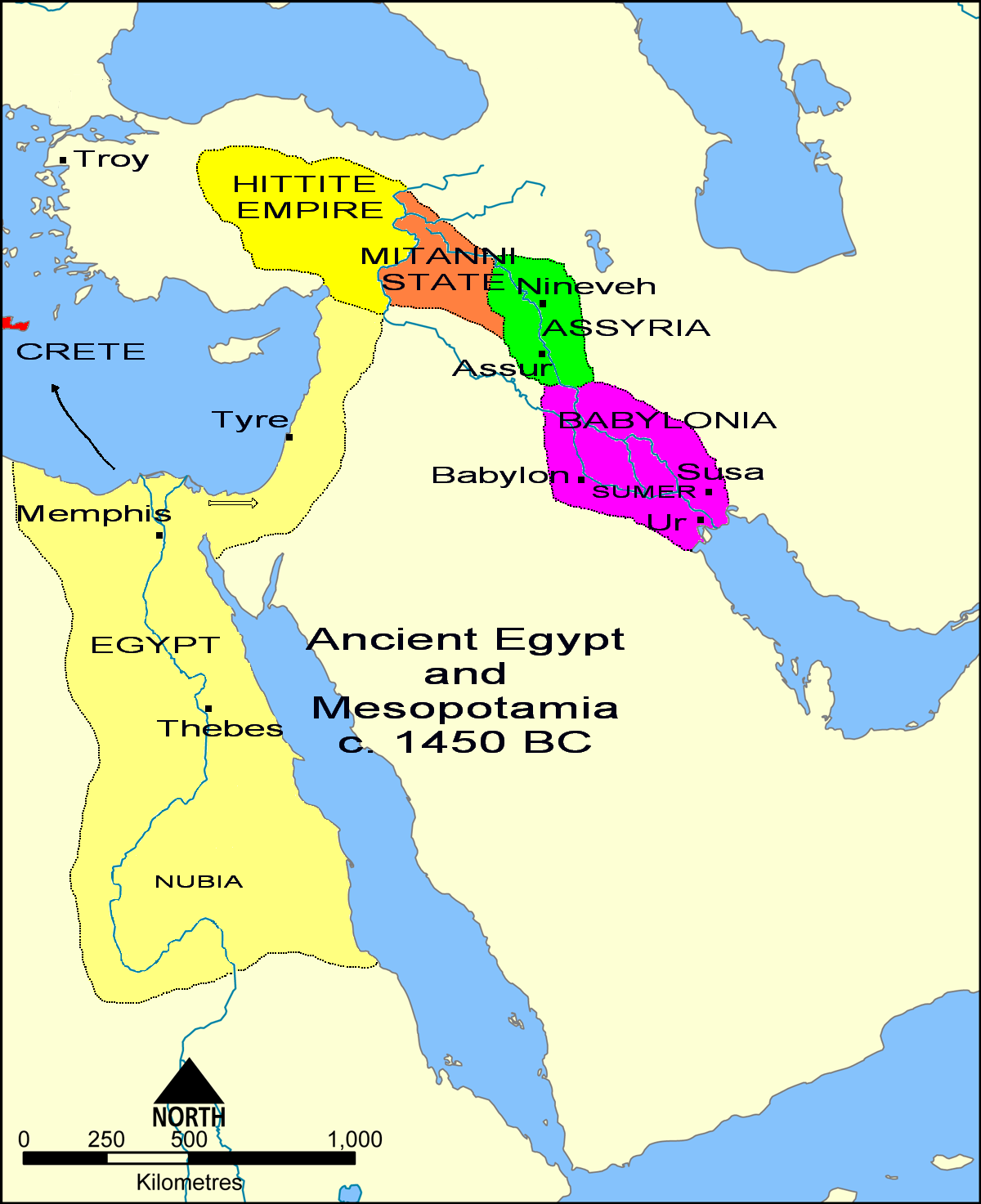

From the development of the earliest cities in Mesopotamia and Egypt until the 18th century, an equilibrium existed between the vast majority of the population who engaged in subsistence agriculture in a rural context, and small centres of populations in the towns where economic activity consisted primarily of trade at markets and manufactures on a small scale. Due to the primitive and relatively stagnant state of agriculture throughout this period the ratio of rural to urban population remained at a fixed equilibrium.

With the onset of the agricultural and industrial revolution in the late 18th century this relationship was finally broken and an unprecedented growth in urban population took place over the course of the 19th century, both through continued migration from the countryside and due to the tremendous demographic expansion that occurred at that time. In England, the urban population jumped from 17% in 1801 to 72% in 1891 (for other countries the figure was: 37% in France, 41% in Prussia and 28% in the United States).

As labourers were freed up from working the land due to higher agricultural productivity they converged on the new industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham which were experiencing a boom in commerce, trade and industry.

Growing trade around the world also allowed cereals to be imported from North America and refrigerated meat from Australasia and South America. Spatially, cities also expanded due to the development of public transport systems, which facilitated commutes of longer distances to the city centre for the working class.

Urbanization rapidly spread across the Western world and, since the 1950s, it has begun to take hold in the developing world as well. At the turn of the 20th century, just 15% of the world population lived in cities. According to the UN the year 2007 witnessed the turning point when more than 50% of the world population was living in cities, for the first time in human history.

This unprecedented movement of people is forecast to continue and intensify in the next few decades, mushrooming cities to sizes incomprehensible only a century ago. Indeed, today, in Asia the urban agglomerations of Dhaka, Karachi, Jakarta, Mumbai, Delhi, Manila, Seoul and Beijing are each already home to over 20 million people, while the Pearl River Delta, Shanghai-Suzhou and Tokyo are forecast to approach or exceed 40 million people each within the coming decade. Outside Asia, Mexico City, Sao Paulo, New York City, Lagos and Cairo are fast approaching being, or are already, home to over 20 million people.

Urartians

Urartians share mostly of their history together with the Hurrians, excepet that Urartians didn’t take part in the formation of the Hurrian Late Bronze Age kingdom of Mitanni, but continued their existence in states as Nairi (KUR.KUR Na-i-ri, also Na-‘i-ru) and later Urartu (Armenian: Urartu, Assyrian: māt Urarṭu; Babylonian: Urashtu).

The name Urartu (Armenian: Urartu, Assyrian: māt Urarṭu; Babylonian: Urashtu), corresponding to Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili – from which is derived the Armenian toponym “Van”), comes from Assyrian sources.

The Assyrian King Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BC or 1263–1234 BC) recorded a campaign in which he subdued the entire territory of “Uruatri” in 1274 BC. Uruartri itself was in the region centred around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands.

The Shalmaneser text uses the name Uratri to refer to a geographical region, not a kingdom. The Assyrian inscriptions mention Uruartri as one of the states of Nairi which he conquered and names eight “lands” contained within Urartu (which at the time of the campaign were still disunited).

Shubria, also known as Subartu, was part of the Urartu confederation. Later, there is reference to a district in the area called Arme or Urme, which some scholars have linked to the name Armenia.

Strictly speaking, Urartu is the Assyrian term for a geographical region, while “kingdom of Urartu” or “Biainili lands” are terms used in modern historiography for the Iron Age state that arose in that region. The kingdom rose to power in the mid-9th century BC, but was conquered by Media in the early 6th century BC.

That a distinction should be made between the geographical and the political entity was already pointed out by König (1955). The landscape corresponds to the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highlands.

According to archaeological data farming on the territory of Urartu began to develop since the Neolithic period, even in the 3rd millennium BC. In Urartian age agriculture was well developed and closely related to the Assyrian on the selection of cultures and ways of processing.

Hurrian & urartian

The Hurro-Urartian language family are an extinct language family of the Ancient Near East, comprising only two known languages: Hurrian and Urartian, both of which were spoken in the triangle made up of the Taurus, Caucasus and Zagros mountains, an area also known as the Armenian highland.

Hurro-Urartian is ergative, agglutinative languages, and is neither related to the Semitic nor to the Indo-European language families. I.M. Diakonoff and S. Starostin see similarities between the Hurro-Urartian languages and the Northeast Caucasian languages, and thus place it in the Alarodian family.

Urartian and Hurrian is closely related. The closeness holds especially true of the so-called Old Hurrian dialect, known above all from Hurro-Hittite bilingual texts, but the two languages must have developed quite independently from approximately 2000 BCE onwards. Although Urartian is not a direct continuation of any of the attested dialects of Hurrian, many of its features are best explained as innovative developments with respect to Hurrian as we know it from the preceding millennium.

Proponents of linguistic macrofamilies have suggested that Hurro-Urartian is part of an “Alarodian” phylum, together with Northeast Caucasian and further as “Macro-Caucasian”, but these theories are without support in mainstream linguistics.

Hurrian is a conventional name for the language of the Hurrians, a people who entered northern Mesopotamia, Syria and the southeastern parts of Anatolia from the Armenian highland around 2300 BC and had mostly vanished by 1000 BC.

Archeologists have discovered the texts of numerous spells, incantations, prophecies and letters at sites including Hattusha, Mari, Tuttul, Babylon, Ugarit and others. The earliest Hurrian text fragments consist of lists of names and places from the end of the third millennium BC. The first full texts date to the reign of king Tish-atal of Urkesh and were found on a stone tablet accompanying the Hurrian foundation pegs known as the “Urkish lions.” At the start of the second milliennium BC.

There have been various Hurrian-speaking states, of which the most prominent one was the kingdom of Mitanni kingdom in northern Mesopotamia (1450–1270 BC), and was likely spoken at least initially in Hurrian settlements in Syria. There was also a Hurrian-Akkadian creole, called Nuzi, spoken in the Mitanni provincial capital of Arrapha.

There was also a strong Hurrian influence on Hittite culture in ancient times, so many Hurrian texts are preserved from Hittite political centres. The Mitanni variety is chiefly known from the so-called “Mitanni letter” from Hurrian Tushratta to pharaoh Amenhotep III surviving in the Amarna archives. The “Old Hurrian” variety is known from some early royal inscriptions and from religious and literary texts, especially from Hittite centres.

The Hurrian of the Mitanni letter differs significantly from that used in the texts at Hattusha and other Hittite centres, as well as from earlier Hurrian texts from various locations. The non-Mitanni letter varieties, while not entirely homogeneous, are commonly subsumed under the designation Old Hurrian.

In the thirteenth century BC, invasions from the west by the Hittites and the south by the Assyrians brought the end of the Mitanni empire, which was divided between the two conquering powers. In the following century, attacks by the Sea Peoples brought a swift end to the last vestiges of the Hurrian language.

It is around this time that other languages, such as the Hittite language and the Ugaritic language also became extinct, in what is known as the Bronze Age collapse. In the texts of these languages, as well as those of Akkadian or Urartian, many Hurrian names and places can be found.

Urartian, Vannic, and (in older literature) Chaldean (Khaldian, or Haldian), is attested from the late 9th century BC to the late 7th century BC as the official written language of the state of Urartu and was probably spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu that was located in the region of Lake Van, with its capital near the site of the modern town of Van, in the Armenian Highland, modern-day Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey.

It was probably spoken by the majority of the population in the mountainous areas around Lake Van and the upper Zab valley. It must have branched off from Hurrian approximately at the beginning of second millennium BC.

It has also been proposed that two little known groups, the Nairi and the Mannae, might have been Urartian speakers, but as little is known about them, it is hard to draw any conclusions about what languages they spoke.

First attested in the 9th century BCE, Urartian ceased to be written after the fall of the Urartian state in 585 BCE, and presumably it became extinct due to the fall of Urartu. It must have been replaced by an early form of Armenian, perhaps during the period of Achaemenid Persian rule, although it is only in the fifth century CE that the first written examples of Armenian appear.

It survives in many inscriptions found in the area of the Urartu kingdom, written in the Assyrian cuneiform script. There have been claims of a separate autochthonous script of “Urartian hieroglyphs” but these remain unsubstantiated. The inscription corpus is too sparse to substantiate the hypothesis. It remains unclear whether the symbols in question form a coherent writing system, or represent just a multiplicity of uncoordinated expressions of proto-writing or ad-hoc drawings.

Urartu

Urartu, corresponding to the biblical Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili) was an Iron Age kingdom centred around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands.

Strictly speaking, Urartu is the Assyrian term for a geographical region, while “kingdom of Urartu” or “Biainili lands” are terms used in modern historiography for the Proto-Armenian (Hurro-Urartian) speaking Iron Age state that arose in that region.

That a distinction should be made between the geographical and the political entity was already pointed out by König (1955). The landscape corresponds to the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highlands.

The kingdom rose to power in the mid-9th century BC, but was conquered by Media in the early 6th century BC. The heirs of Urartu are the Armenians and their successive kingdoms.

Urartu comprised an area of approximately 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2), extending from the river Kura in the north, to the northern foothills of the Taurus Mountains in the south; and from the Euphrates in the west to the Caspian sea in the east.

At its apogee, Urartu stretched from the borders of northern Mesopotamia to the southern Caucasus, including present-day Armenia and southern Georgia as far as the river Kura.

Archaeological sites within its boundaries include Altintepe, Toprakkale, Patnos and Cavustepe. Urartu fortresses included Erebuni (present day Yerevan city), Van Fortress, Argishtihinili, Anzaf, Cavustepe and Başkale, as well as Teishebaini (Karmir Blur, Red Mound) and others.

Subartu/Hurrians

The land of Subartu (Akkadian Šubartum/Subartum/ina Šú-ba-ri, Assyrian mât Šubarri) or Subar (Sumerian Su-bir4/Subar/Šubur) is mentioned in Bronze Age literature. The name also appears as Subari in the Amarna letters, and, in the form Šbr, in Ugarit, and came to be known as the Hurrians or Subarians and their country was known as Subir, Subartu or Shubar.

Subartu was apparently a polity in Northern Mesopotamia, at the upper Tigris. Most scholars accept Subartu as an early name for Assyria proper on the Tigris, although there are various other theories placing it sometimes a little farther to the east, north or west of there. Its precise location has not been identified.

From the point of view of the Akkadian Empire, Subartu marked the northern geographical horizon, just as Martu, Elam and Sumer marked “west”, “east” and “south”, respectively.

The Sumerian mythological epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta lists the countries where the “languages are confused” as Subartu, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki (Akkad), and the Martu land (the Amorites).

Similarly, the earliest references to the “four quarters” by the kings of Akkad name Subartu as one of these quarters around Akkad, along with Martu, Elam, and Sumer. Subartu in the earliest texts seem to have been farming mountain dwellers, frequently raided for slaves.

Eannatum of Lagash was said to have smitten Subartu or Shubur, and it was listed as a province of the empire of Lugal-Anne-Mundu; in a later era Sargon of Akkad campaigned against Subar, and his grandson Naram-Sin listed Subar along with Armani (Armenians), -which has been identified with Aleppo-, among the lands under his control. Ishbi-Erra of Isin and Hammurabi also claimed victories over Subar. Aratta has been the oldest state in the Armenian Highland, particularly in the Ayrarat district. Atta means father.

A link between Subarians, who from the earliest historical periods are found not only occupying vast mountainous areas north of Babylonia but also living peacefully within Babylonia side by side with Sumerians and Akkadians, in the east and the much younger Hurrians, who appeared relatively late on the Mesopotamian scene and who played an important role in the history of the Near East in the 2nd millennium BC, in the west was established eventually with the aid of personal names — first from Babylonia and subsequently from Nuzi.

Meanwhile, extra-cuneiform connections of the Hurrians proved to include the biblical Horites as well as sundry Egyptian analogues. With this mounting evidence for the expansion of the Hurrians came also recognition of their substantial influence on other cultures — the Hittite, the Assyrian, and the Canaanite — involving such fields as political history, law and society, religion, art, and linguistics.

The “political and geographic unit” which was one thing to the Babylonians and another thing to the Assyrians. In the former instance it lay ” somewhere between the Tigris, the Zagros Mountains, and the Diyala.” At times it might stand for the whole North.

To the Assyrians, on the other hand, Subartu signified regions in the mountains to the east and north of the Tigris, yet it could extend “sometimes far west into the land of the Amorites and far east into the land of the Elamites.” It is recurring references to the “widespread Subarians ” to the west and northwest of Assyria, which is precisely the territory that figures otherwise as good Hurrian stamping ground.

The Aloridian city culture

The Aloridian urban culture was not represented by a large number of cities. Urkesh was the only Aloridian city in the third millennium BC. In the second millennium BC we know a number of Aloridian cities, such as Arrapha, Harran, Kahat, Nuzi, Taidu and Washukanni – the capital of Mitanni.

Although the site of Washukanni, alleged to be at Tell Fakhariya, is not known for certain, no tell (city mound) in the Khabur Valley much exceeds the size of 1 square kilometer (250 acres), and the majority of sites are much smaller.

The Aloridian urban culture appears to have been quite different from the centralized state administrations of Assyria and ancient Egypt. An explanation could be that the feudal organization of the Aloridian kingdoms did not allow large palace or temple estates to develop.

Aloridian settlements are distributed over three modern countries, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. The heart of the Aloridian world is dissected by the modern border between Syria and Turkey. Several sites are situated within the border zone, making access for excavations problematic.

A threat to the ancient sites are the dam many projects in the Euphrates, Tigris and Khabur valleys. Several rescue operations have already been undertaken when the construction of dams put entire river valleys under water.

The tells, or city mounds, often reveal a long occupation beginning in the Neolithic and ending in the Roman period or later. The characteristic Aloridian pottery, the Khabur ware, is helpful in determining the different strata of occupation within the mounds.

The Aloridian settlements are usually identified from the Middle Bronze Age to the end of the Late Bronze Age, with Tell Mozan (Urkesh) being the main exception.

The first major excavations of Aloridian sites in Iraq and Syria began in the 1920s and 1930s. They were led by the American archaeologist Edward Chiera at Yorghan Tepe (Nuzi), and the British archaeologist Max Mallowan at Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak.

Recent excavations and surveys in progress are conducted by American, Belgian, Danish, Dutch, French, German and Italian teams of archaeologists, with international participants, in cooperation with the Syrian Department of Antiquities.

Haplogroup R1b

It has been hypothetised that R1b people (perhaps alongside neighbouring J2 tribes) were the first to domesticate cattle in northern Mesopotamia some 10,500 years ago. R1b tribes descended from mammoth hunters, and when mammoths went extinct, they started hunting other large game such as bisons and aurochs.

With the increase of the human population in the Fertile Crescent from the beginning of the Neolithic (starting 12,000 years ago), selective hunting and culling of herds started replacing indiscriminate killing of wild animals.

The increased involvement of humans in the life of aurochs, wild boars and goats led to their progressive taming. Cattle herders probably maintained a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence, while other people in the Fertile Crescent (presumably represented by haplogroups E1b1b, G and T) settled down to cultivate the land or keep smaller domesticates.

The analysis of bovine DNA has revealed that all the taurine cattle (Bos taurus) alive today descend from a population of only 80 aurochs. The earliest evidence of cattle domestication dates from circa 8,500 BCE in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic cultures in the Taurus Mountains.

The two oldest archaeological sites showing signs of cattle domestication are the villages of Çayönü Tepesi in southeastern Turkey and Dja’de el-Mughara in northern Iraq, two sites only 250 km away from each others. This is presumably the area from which R1b lineages started expanding – or in other words the “original homeland” of R1b.

The early R1b cattle herders would have split in at least three groups. One branch (M335) remained in Anatolia, but judging from its extreme rarity today wasn’t very successful, perhaps due to the heavy competition with other Neolithic populations in Anatolia, or to the scarcity of pastures in this mountainous environment.

A second branch migrated south to the Levant, where it became the V88 branch. Some of them searched for new lands south in Africa, first in Egypt, then colonising most of northern Africa, from the Mediterranean coast to the Sahel. The third branch (P297), crossed the Caucasus into the vast Pontic-Caspian Steppe, which provided ideal grazing grounds for cattle.

They split into two factions: R1b1a1 (M73), which went east along the Caspian Sea to Central Asia, and R1b1a2 (M269), which at first remained in the North Caucasus and the Pontic Steppe between the Dnieper and the Volga.

It is not yet clear whether M73 actually migrated across the Caucasus and reached Central Asia via Kazakhstan, or if it went south through Iran and Turkmenistan. In the latter case, M73 might not be an Indo-European branch of R1b, just like V88 and M335.

R1b-M269 (the most common form in Europe) is closely associated with the diffusion of Indo-European languages, as attested by its presence in all regions of the world where Indo-European languages were spoken in ancient times, from the Atlantic coast of Europe to the Indian subcontinent, which comprised almost all Europe (except Finland, Sardinia and Bosnia-Herzegovina), Anatolia, Armenia, European Russia, southern Siberia, many pockets around Central Asia (notably in Xinjiang, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan), without forgetting Iran, Pakistan, northern India and Nepal. The history of R1b and R1a are intricately connected to each others.

Haplogroup J2

Haplogroup J2 is thought to have appeared somewhere in the Middle East towards the end of the last glaciation, between 15,000 and 22,000 years ago. Its present geographic distribution argues in favour of a Neolithic expansion from the Fertile Crescent.

This expansion probably correlated with the diffusion of domesticated of cattle and goats (starting c. 8000-9000 BCE) from the Zagros Mountains and northern Mesopotamia, rather than with the development of cereal agriculture in the Levant (which appears to be linked rather to haplogroups G2 and E1b1b).

A second expansion of J2 could have occured with the advent of metallurgy, notably copper working (from the Lower Danube valley, central Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia), and the rise of some of the oldest civilisations.

The world’s highest frequency of J2 is found among the Ingush (88% of the male lineages) and Chechen (56%) people in the Northeast Caucasus. Both belong to the Nakh ethnic group, who have inhabited that territory since at least 3000 BCE. Their language is distantly related to Dagestanian languages, but not to any other linguistic group.

However, Dagestani peoples (Dargins, Lezgins, Avars) belong predominantly to haplogroup J1 (84% among the Dargins) and almost completely lack J2 lineages.

Other high incidence of haplogroup J2 are found in many other Caucasian populations, including the Azeri (30%), the Georgians (27%), the Kumyks (25%), and the Armenians (22%).

Nevertheless, it is very unlikely that haplogroups J2 originated in the Caucasus because of the low genetic diversity in the region. Most Caucasian people belong to the same J2a4b (M67) subclade. The high local frequencies observed would rather be the result of founder effects, for instance the proliferation of chieftains and kings’s lineages through a long tradition of polygamy, a practice that the Russians have tried to suppress since their conquest of the Caucasus in the 19th century.

Outside the Caucasus, the highest frequencies of J2 are observed in Cyprus (37%), Crete (34%), northern Iraq (28%), Lebanon (26%), Turkey (24%, with peaks of 30% in the Marmara region and in central Anatolia), Greece (23%), Central Italy (23%), Sicily (23%), South Italy (21.5%), and Albania (19.5%), as well as among Jewish people (19 to 25%).

One fourth of the Vlach people (isolated communities of Romance language speakers in the Balkans) belong to J2, considerably more than the average of Macedonia and northern Greece where they live. This, combined to the fact that they speak a language descended from Latin, suggests that they could have a greater part of Roman (or at least Italian) ancestry than other ethnic groups in the Balkans.

Notwithstanding its strong presence in West Asia today, haplogroup J2 does not seem to have been one of the principal lineages associated with the rise and diffusion of cereal farming from the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia to Europe.

The region of origin of J2 is still unclear at present. It is likely that J2 men had settled over most of Anatolia, the South Caucasus and Iran by the end of the Last Glaciation 12,000 years ago.

It is possible that J2 hunter-gatherers then goat/sheep herders also lived in the Fertile Crescent during the Neolithic period, although the development of early cereal agriculture is thought to have been conducted by men belonging primarily to haplogroups E1b1b and G2a.

The first expansion of J2 into Europe probably happened during the Late Glacial and immediate postglacial periods (c. 16 to 10 kya), when Anatolian hunter-gatherers moved into the Balkans. This migration would have included J2b and E-V13 male lineages and assorted J and T maternal lineages (presumably J1c, J2a1, T1a1, T2a1b, T2b, T2e and T2f1).

This population would have occupied the modern regions of western Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria. When farmers and herders expanded from the Fertile Crescent during the Early Neolithic, they would have blended with one another before expanding towards Central Europe and Italy.

J2b seems to have split in two subclades soon after leaving Anatolia, with J2b1 being found mostly in western Anatolia and Greece, while J2b2 expanded from the Balkans to most of Europe, to Central Asia, India and back to the Middle East.

It is very likely that J2a, J1 and G2a were the three dominant male lineages the Early Bronze Age Kura-Araxes culture, which expanded from the South Caucasus to eastern Anatolia, northern Mesopotamia and the western Iran. From then on, J2 men would have definitely have represented a sizeable portion of the population of Bronze and Iron Age civilizations such as the Hurrians, the Assyrians or the Hittites.

Quite a few ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilisations flourished in territories where J2 lineages were preponderant. This is the case of the Hattians, the Hurrians, the Etruscans, the Minoans, the Greeks, the Phoenicians (and their Carthaginian offshoot), the Israelites, and to a lower extent also the Romans, the Assyrians and the Persians. All the great seafaring civilisations from the middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age were dominated by J2 men.

There is a distinct association of ancient J2 civilisations with bull worship. The oldest evidence of a cult of the bull can be traced back to Neolithic central Anatolia, notably at the sites of Çatal Höyük and Alaca Höyük. Bull depictions are omnipresent in Minoan frescos and ceramics in Crete.

Bull-masked terracotta figurines and bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus (dating back as far as the Neolithic, the first presumed expansion of J2 from West Asia). The Hattians, Sumerians, Babylonians, Canaaites, and Carthaginians all had bull deities (in contrast with Indo-European or East Asian religions).

The sacred bull of Hinduism, Nandi, present in all temples dedicated to Shiva or Parvati, does not have an Indo-European origin, but can be traced back to Indus Valley civilisation.

Minoan Crete, Hittite Anatolia, the Levant, Bactria and the Indus Valley also shared a tradition of bull leaping, the ritual of dodging the charge of a bull. It survives today in the traditional bullfighting of Andalusia in Spain and Provence in France, two regions with a high percentage of J2 lineages.

Haplogroup J1

Since the discovery of haplogroup J it has generally been recognized that it shows signs of having originated in or near West Asia. The frequency and diversity of both its major branches, J1 and J2, in that region makes them candidates as genetic markers of the spread of farming technology during the Neolithic, which is proposed to have had a major impact upon human populations.

J1 has several recognized subclades, some of which were recognized before J1 itself was recognized, for example J-M62 Y Chromosome Consortium “YCC” 2002. With one notable exception, J-P58, most of these are not common. Because of the dominance of J-P58 in J1 populations in many areas, discussion of J1’s origins requires a discussion of J-P58 at the same time.

The P58 marker which defines subgroup J-P58 is very prevalent in many areas where J1 is common, especially in parts of North Africa and throughout the Arabian Peninsula. It also makes up approximately 70% of the J1 among the Amhara of Ethiopia. Notably, it is not common among the J1 populations in the Caucasus.

Chiaroni 2009 proposed that J-P58 (that they refer to as J1e) might have first dispersed during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, “from a geographical zone, including northeast Syria, northern Iraq and eastern Turkey toward Mediterranean Anatolia, Ismaili from southern Syria, Jordan, Palestine and northern Egypt.”

They further propose that the Zarzian material culture may be ancestrals. They also propose that this movement of people may also be linked to the dispersal of Semitic languages by hunter-herders, who moved into arid areas during periods known to have had low rainfall.

Thus, while other haplogroups including J2 moved out of the area with agriculturalists, which followed the rainfall, populations carrying J1 remained with their flocks.

According to this scenario, after the initial neolithic expansion involving Semitic languages, which possibly reached as far as Yemen, a more recent dispersal occurred during the Chalcolithic or Early Bronze Age (approximately 3000–5000 BCE), and this involved the branch of Semitic which leads to the Arabic language.

The authors propose that this involved a spread of some J-P58 from the direction of Syria towards Arab populations of the Arabian Peninsula and Negev.

Hanbi

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology Hanbi or Hanpa (more commonly known in western text) was the father of Enki, Pazuzu, the king of the demons of the wind, the bearer of storms and drought, and Humbaba, also Humbaba the Terrible, a monstrous giant of immemorial age raised by Utu, the Sun.

Although Pazuzu is, himself, an evil spirit, he drives away other evil spirits, therefore protecting humans against plagues and misfortunes. Humbaba was the guardian of the Cedar Forest, where the gods lived, by the will of the god Enlil.

Enki (Eridu)

Enki (Sumerian: EN.KI(G)) is a god in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

Enki was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation (Nudimmud: nu, likeness, dim mud, make beer).

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

Enki was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. His image is a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, sometimes confused with the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40,” occasionally referred to as his “sacred number.”

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”: the Sumerian en is translated as a title equivalent to “lord”; it was originally a title given to the High Priest; ki means “earth”; but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

The main temple to Enki is in Sumerian called E-abzu (E-A), meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

Enkidu

Enkidu (EN.KI.DU3 “Enki’s creation”), earlier transliterated as Enkimdu, Eabani or Enkita, is a central figure in the Ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh. In the story the gods created a man (1/3 man and 2/3 animal) and named him Enkidu, who was created by the gods as the rival to the mighty Gilgamesh. He was formed from clay and saliva by the goddess Aruru, the goddess of creation, to rid Gilgamesh of his arrogance.

God made Adam from clay from the soil too. Both were made to do the will of the god(s), nothing more. They were both made from the same material, in the same way, for the same basic purpose. The difference is that Adam was made by a god, while Enkidu was made by a goddess. So, in the 1500 years separating these two books, women went from being respected while working as prostitutes in the temple to being the first sinner.

Enkidu had beauty and strength only matched by the king, Gilgamesh. He is a wild man, raised by animals and ignorant of human society. Gilgamesh sends out a Temple Prostitute to seduce him, Shamhat, who plays the integral role of taming the wild man Enkidu, because if she had sex with him, the other animals wouldn’t accept him, and he could be civilized.

The goddess who made Enkidu decides that the best way to make Gilgamesh follow their will is to create an equal and teach him humility. But, when the Jews create their God, his solution to the problem of humanity sinning is to “banish him from the Garden of Eden” and “he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life”.

Gilgamesh sleeps with every virgin before her husband can, and they make an equal man to teach him. Adam and Eve eat one apple and they get kicked out and God puts a guy with a freaking flaming sword there to keep them out.

In Genesis a man (Adam) is alone in a natural setting (the garden of Eden) until a woman (Eve) comes to him and does something (eats the forbidden apple) and gets them expelled. The similarities and differences in the stories show similarities and differences in beliefs over time.

She uses her attractiveness to tempt Enkidu from the wild, and his ‘wildness’, civilizing him through continued sexual intercourse. Unfortunately for Enkidu, after he enjoys Shamhat for “six days and seven nights”, his former companions, the wild animals, turn away from him in fright, at the watering hole where they congregated.

According to Adam and Eve, the first two people NEVER had sex while they were perfect. They didn’t have any kids while in the garden. It was only after they discovered sin that they discovered sex. Sex is considered evil in the bible.

The Sumerians were amazed at the power of sex to make another human. Sex was such an incredible thing to them that they even had prostitutes working in the temple to share its wonders with other people. In the story of Gilgamesh, Shamhat, the temple prostitute, is considered trustworthy enough to be entrusted with the task of teaching Enkidu how to be a civilized human.

Shamhat persuades him to follow her and join the civilized world in the city of Uruk, where Gilgamesh is king, rejecting his former life in the wild with the wild animals of the hills. Henceforth, Gilgamesh and Enkidu become the best of friends and undergo many adventures.

Enkidu embodies the wild or natural world, and though equal to Gilgamesh in strength and bearing, acts in some ways as an antithesis to the cultured, urban-bred warrior-king.

Enkidu then becomes the king’s constant companion and deeply beloved friend, accompanying him on adventures until he is stricken ill. The deep, tragic loss of Enkidu profoundly inspires in Gilgamesh a quest to escape death by obtaining godly immortality.

Ninti

Ninti, the title of Ninhursag, also means “the mother of all living”, and was a title given to the later Hurrian goddess Kheba, later known as Cybele. This is also the title given in the Bible to Eve, the Hebrew and Aramaic Ḥawwah (חוה), who was made from the rib of Adam, in a strange reflection of the Sumerian myth, in which Adam — not Enki — walks in the Garden of Paradise.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water’”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

Continuation

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael), with Ia.

Jean Bottero (1952) and others suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea, Enki’s Akkadian name, associating the Canaanite theonym Yahu, and ultimately Hebrew YHWH.

This hypothesis is dismissed by some scholars as erroneous, based on a mistaken cuneiform reading, but academic debate continues. Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic Yamm (sea), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw, or Ya’a.

Isimud

Enki was accompanied by an attendant Isimud (also Isinu; Usmû; Usumu (Akkadian), a minor god, the messenger of the god Enki in Sumerian mythology. He is readily identifiable by the fact that he possesses two faces looking in opposite directions.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is the god of beginnings and transitions, and thereby of gates, doors, doorways, passages and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces, since he looks to the future and to the past. The Romans named the month of January (Ianuarius) in his honor.

Mercury

The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki. Mercury is the ruling planet of Gemini and Virgo and is exalted in the latter; it is the only planet with rulership and exaltation both in the same sign (Virgo).

Hermes is an Olympian god in Greek religion and mythology, son of Zeus and the Pleiad Maia. He is second youngest of the Olympian gods. He is a god of transitions and boundaries.

Hermes is quick and cunning, and moved freely between the worlds of the mortal and divine, as emissary and messenger of the gods, intercessor between mortals and the divine, and conductor of souls into the afterlife. He is protector and patron of travelers, herdsmen, thieves, orators and wit, literature and poets, athletics and sports, invention and trade.

In some myths he is a trickster, and outwits other gods for his own satisfaction or the sake of humankind. His attributes and symbols include the herma, the rooster and the tortoise, purse or pouch, winged sandals, winged cap, and his main symbol is the herald’s staff, the Greek kerykeion or Latin caduceus which consisted of two snakes wrapped around a winged staff.

“Hermes” may be related to Greek ἑρμηνεύς hermeneus (“interpreter”), reflecting Hermes’s function as divine messenger. The word “hermeneutics”, the study and theory of interpretation, is derived from hermeneus.

In the Roman adaptation of the Greek pantheon Hermes is identified with the Roman god Mercury, who, though inherited from the Etruscans, developed many similar characteristics, such as being the patron of commerce.

In Roman mythology, Mercury is the messenger of the gods, noted for his speed and swiftness. Echoing this, the scorching, airless world Mercury circles the Sun on the fastest orbit of any planet.

Mercury takes only 88 days to orbit the Sun, spending about 7.33 days in each sign of the zodiac. Mercury is so close to the Sun that only a brief period exists after the Sun has set where it can be seen with the naked eye, before following the Sun beyond the horizon.

Astrologically, Mercury represents the principles of communication, mentality, thinking patterns, rationality and reasoning and adaptability and variability. Mercury governs schooling and education, the immediate environment of neighbors, siblings and cousins, transport over short distances, messages and forms of communication such as post, email and telephone, newspapers, journalism and writing, information gathering skills and physical dexterity. The 1st-century poet Manilius described Mercury as an inconstant, vivacious and curious planet.

In medicine, Mercury is associated with the nervous system, the brain, the respiratory system, the thyroid and the sense organs. It is traditionally held to be essentially cold and dry, according to its placement in the zodiac and in any aspects to other planets. It is linked to the animal spirits.

Today, Mercury is regarded as the ruler of the third and sixth houses; traditionally, it had the joy in the first house. Mercury is the messenger of the gods in mythology. It is the planet of day-to-day expression and relationships. Mercury’s action is to take things apart and put them back together again. It is an opportunistic planet, decidedly unemotional and curious.

Mercury rules over Wednesday. In Romance languages, the word for Wednesday is often similar to Mercury (miercuri in Romanian, mercredi in French, miercoles in Spanish and mercoledì in Italian). Dante Alighieri associated Mercury with the liberal art of dialectic.

In Indian astrology, Mercury is called Budha, a word related to Buddhi (“intelligence”) and represents communication. In Chinese astrology, Mercury represents Water, the fourth element, therefore symbolizing communication, intelligence and elegance.

The Chinese linkage of Mercury with Water is alien to Western astrology, but this combination shares the water themes, much of what is coined “mercurial” in Western thought, such as intellect, reason and communication.

Capricorn

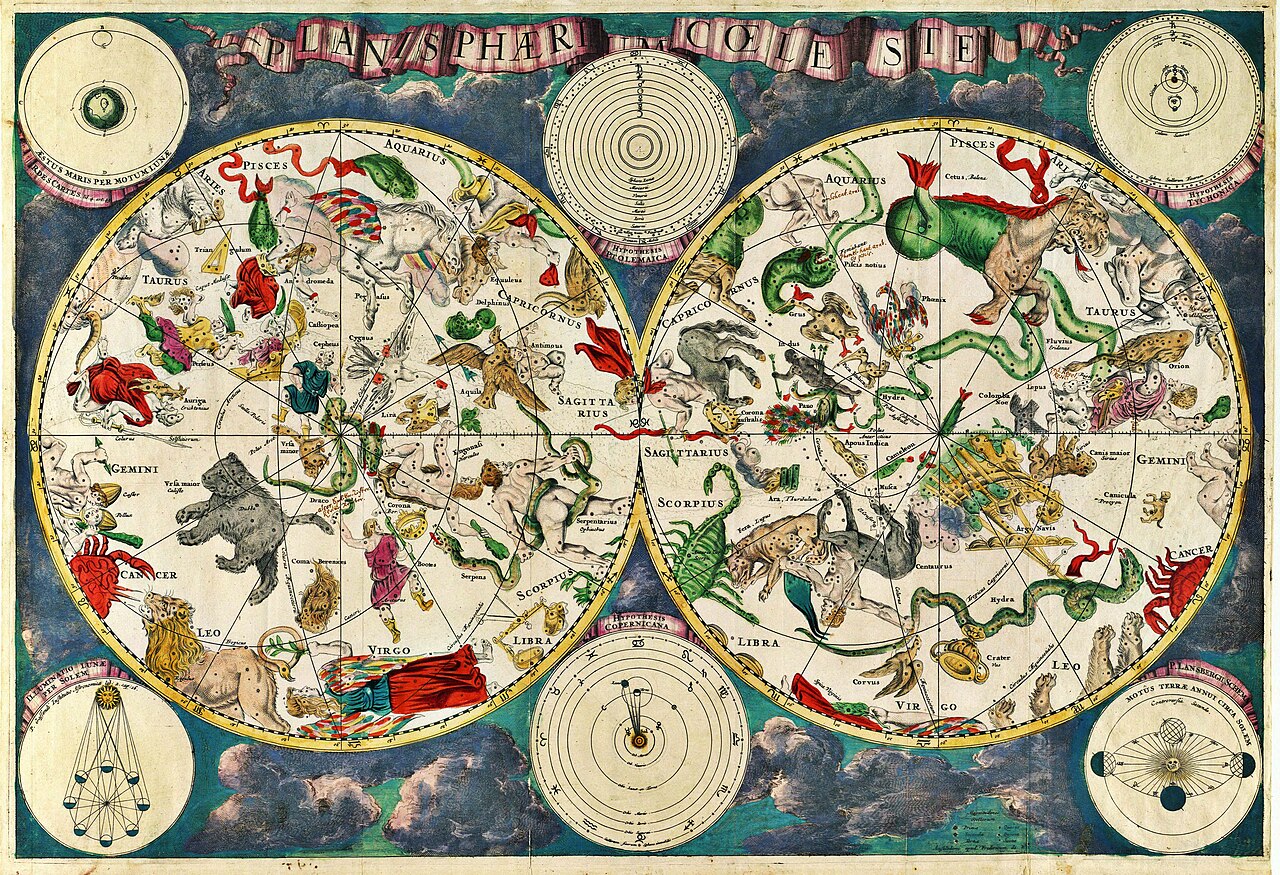

Capricorn, called by the Nakh peoples as Roofing Towers (Chechen: Neģara Bjovnaš), is the tenth astrological sign in the zodiac, originating from the constellation of Capricornus. It spans the 270–300th degree of the zodiac, corresponding to celestial longitude. In astrology, Capricorn is considered an earth sign, introvert sign, and one of the four cardinal signs.

Under the tropical zodiac, the sun transits this area from December 22 to January 19 each year, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun currently transits the constellation of Capricorn from approximately January 15 to February 14.

Capricorn-Sagittarius cusps (those born from December 21 to December 28) are considered to be slightly different from the typical Capricorn, being more outgoing, jovial and less ambitious and money orientated than the Capricorn who is not born on a cusp.

Despite its faintness, Capricornus has one of the oldest mythological associations, having been consistently represented as a hybrid of a goat and a fish since the Middle Bronze Age.

The Encyclopedia Britannica states that the figure of Capricorn derives from the half-goat, half-fish representation of the Sumerian god Enki (Sumerian: EN.KI(G)), later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology.

First attested in depictions on a cylinder-seal from around the 21st century BC, it was explicitly recorded in the Babylonian star catalogues as MULSUḪUR.MAŠ “The Goat-Fish” before 1000 BC. The constellation was a symbol of the god Ea and in the Early Bronze Age marked the winter solstice.

Due to the precession of the equinoxes the December solstice no longer takes place while the sun is in the constellation Capricornus, as it did until 130 BCE, but the astrological sign called Capricorn begins with the solstice. The solstice now takes place when the Sun is in Sagittarius.

The sun’s most southerly position, which is attained at the northern hemisphere’s winter solstice, is now called the Tropic of Capricorn, a term which also applies to the line on the Earth at which the sun is directly overhead at noon on that solstice. The Sun is now in Capricorn from late January through mid-February.

The goat’s broken horn was transformed into the cornucopia or horn of plenty. Capricornus is also sometimes identified as Pan, the god with a goat’s head, who saved himself from the monster Typhon by giving himself a fish’s tail and diving into a river.

The planet Neptune was discovered in Capricornus by German astronomer Johann Galle, near Deneb Algedi (δ Capricorni) on September 23, 1846, which is appropriate as Capricornus can be seen best from Europe at 4:00am in September.

Amalthea

In Greek mythology, the constellation is sometimes mixed with Amalthea, the goat that suckled the infant Zeus after his mother, Rhea, saved him from being devoured by his father, Cronos.

In Greek mythology, Amalthea or Amaltheia is the most-frequently mentioned foster-mother of Zeus. Her name in Greek (“tender goddess”) is clearly an epithet, signifying the presence of an earlier nurturing goddess, whom the Hellenes, whose myths we know, knew to be located in Crete, where Minoans may have called her a version of “Dikte”.

In the tradition represented by Hesiod’s Theogony, Cronus swallowed all of his children immediately after birth. The mother goddess Rhea, Zeus’ mother, deceived her brother consort Cronus by giving him a stone wrapped to look like a baby instead of Zeus.

Since she instead gave the infant Zeus to Adamanthea to nurse in a cave on a mountain in Crete, it is clear that Adamanthea is a doublet of Amalthea. In many literary references, the Greek tradition relates that in order that Cronus should not hear the wailing of the infant, Amalthea gathered about the cave the Kuretes or the Korybantes to dance, shout, and clash their spears against their shields.

“Amaltheia was placed amongst the stars as the constellation Capra—the group of stars surrounding Capella on the arm (ôlenê) of Auriga the Charioteer.” Capra simply means “she-goat” and the star-name Capella is the “little goat”, but some modern readers confuse her with the male sea-goat of the Zodiac, Capricorn, who bears no relation to Amalthea, no connection in a Greek or Latin literary source nor any ritual or inscription to join the two.

Saturn

In astrology, a planet’s domicile is the zodiac sign over which it has rulership. The planet said to be ruler of Capricorn is Saturn. Saturn is the ruling planet of Capricorn and is exalted in Libra.

Saturn is associated with Saturday, which was named after the deity Saturn. Dante Alighieri associated Saturn with the liberal art of astronomia (astrology and astronomy). Saturn the planet and Saturday are both named after the god.

In Roman mythology, Saturn is the god of agriculture, founder of civilizations and of social order, and conformity. The glyph is most often seen as scythe-like, but it is primarily known as the “crescent below the cross”, whereas Jupiter’s glyph is the “crescent above the cross”. The famous rings of the planet Saturn that enclose and surround it, reflect the idea of human limitations.

Astrologically, Saturn is associated with the principles of limitation, restrictions, boundaries, practicality and reality, crystallizing, and structures. Saturn governs ambition, career, authority and hierarchy, and conforming social structures.

It concerns a person’s sense of duty, discipline and responsibility, and their physical and emotional endurance during hardships. Saturn is also considered to represent the part of a person concerned with long-term planning.

Before the discovery of Uranus, Saturn was regarded as the ruling planet of Aquarius. Many astrologers still use Saturn as the planetary ruler of both Capricorn and Aquarius; in modern astrology it is accordingly the ruler of the tenth and eleventh houses. Traditionally, however, Saturn was associated with the first and eighth houses.

In Indian astrology, Saturn is called Shani or “Sani”, and represents career and longevity. It is also the bringer of bad luck and hardship. In Chinese astrology, Saturn is ruled by the element earth, which is warm, generous, and co-operative.

Pegasus

Pegasus is a constellation in the northern sky, named after the winged horse Pegasus, a winged horse with magical powers, in Greek mythology. It was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. Twelve star systems have been found to have exoplanets.

With an apparent magnitude varying between 2.37 and 2.45, the brightest star in Pegasus is the orange supergiant Epsilon Pegasi, also known as Enif, which marks the horse’s muzzle.

Alpha (Markab), Beta (Scheat), and Gamma (Algenib), together with Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz or Sirrah) form the large asterism known as the Square of Pegasus.

Enki was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). The Babylonian constellation IKU (field) had four stars of which three were later part of the Greek constellation Hippos (Pegasus).

Pegasus, one of the best known creatures in Greek mythology, is a winged divine stallion usually depicted as pure white in color. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as horse-god, and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa. He was the brother of Chrysaor, born at a single birthing when his mother was decapitated by Perseus.

Greco-Roman poets write about his ascent to heaven after his birth and his obeisance to Zeus, king of the gods, who instructed him to bring lightning and thunder from Olympus.

One myth regarding his powers says that his hooves dug out a spring, Hippocrene, the fountain on Mt. Helicon, which blessed those who drank its water with the ability to write poetry. Pegasus was the one who delivered Medusa’s head to Polydectes, after which he travelled to Mount Olympus in order to be the bearer of thunder and lightning for Zeus.

Eventually, he was captured by the Greek hero Bellerophon, who was asked to kill the Chimera, near the fountain Peirene with the help of Athena and Poseidon. Pegasus allows the hero to ride him to defeat a monster, the Chimera, before realizing many other exploits.

Despite this success, after the death of his children, Bellerophon asked Pegasus to take him to Mount Olympus. Though Pegasus agreed, Bellerophon falls off his back trying to reach Mount Olympus. He plummeted back to Earth after Zeus either threw a thunderbolt at him or made Pegasus buck him off.

From earliest times white horses have been mythologized as possessing exceptional properties, transcending the normal world by having wings (e.g. Pegasus from Greek mythology), or having horns (the unicorn).

As part of its legendary dimension, the white horse in myth may be depicted with seven heads (Uchaishravas) or eight feet (Sleipnir), sometimes in groups or singly. There are also white horses which are divinatory, who prophesy or warn of danger.

Personification of the water, solar myth, or shaman mount, Carl Jung and his followers have seen in Pegasus a profound symbolic esoteric in relation to the spiritual energy that allows access to the realm of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Poseidon/ Neptune

Poseidon is one of the twelve Olympian deities of the pantheon in Greek mythology. His main domain is the ocean, and he is called the “God of the Sea”. Additionally, he is referred to as “Earth-Shaker” due to his role in causing earthquakes, and has been called the “tamer of horses”. He is usually depicted as an older male with curly hair and beard.

There is some reason to believe that Poseidon, like other water gods, was originally conceived under the form of a horse. In Greek art, Poseidon rides a chariot that was pulled by a hippocampus or by horses that could ride on the sea, and sailors sometimes drowned horses as a sacrifice to Poseidon to ensure a safe voyage.

The name of the sea-god Nethuns in Etruscan was adopted in Latin for Neptune (Latin: Neptūnus) in Roman mythology; both were sea gods analogous to Poseidon.

Neptune was the Roman god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune was the brother of Jupiter and Pluto, each of them presiding over the realms of Heaven, our earthly world, and the Underworld, respectively. Salacia was his consort.

Depictions of Neptune in Roman mosaics, especially those of North Africa, are influenced by Hellenistic conventions. Neptune was likely associated with fresh water springs before the sea. Like Poseidon, Neptune was worshipped by the Romans also as a god of horses, under the name Neptunus Equester, a patron of horse-racing.

Linear B tablets show that Poseidon was venerated at Pylos and Thebes in pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece as a chief deity, but he was integrated into the Olympian gods as the brother of Zeus and Hades.

According to some folklore, he was saved by his mother Rhea, who concealed him among a flock of lambs and pretended to have given birth to a colt, which was devoured by Cronos.

There is a Homeric hymn to Poseidon, who was the protector of many Hellenic cities, although he lost the contest for Athens to Athena. According to the references from Plato in his dialogue Timaeus and Critias, the island of Atlantis was the chosen domain of Poseidon.

The earliest attested occurrence of the name, written in Linear B, is Po-se-da-o or Po-se-da-wo-ne, which correspond to Poseidaōn and Poseidawonos in Mycenean Greek; in Homeric Greek it appears as Poseidaōn; in Aeolic as Poteidaōn; and in Doric as Poteidan, Poteidaōn, and Poteidas.

A common epithet of Poseidon is Gaiēochos, “Earth-shaker,” an epithet which is also identified in Linear B tablets. Another attested word, E-ne-si-da-o-ne, recalls his later epithets Ennosidas and Ennosigaios indicating the chthonic nature of Poseidon.

The origins of the name “Poseidon” are unclear. One theory breaks it down into an element meaning “husband” or “lord” (Greek posis), from PIE *pótis) and another element meaning “earth” (da), Doric for (gē), producing something like lord or spouse of Da, i.e. of the earth; this would link him with Demeter, “Earth-mother.” Walter Burkert finds that “the second element da- remains hopelessly ambiguous” and finds a “husband of Earth” reading “quite impossible to prove.”

Another theory interprets the second element as related to the word dâwon, “water”; this would make *Posei-dawōn into the master of waters. There is also the possibility that the word has Pre-Greek origin. Plato in his dialogue Cratylus gives two alternative etymologies: either the sea restrained Poseidon when walking as a “foot-bond”, or he “knew many things”.

If surviving Linear B clay tablets can be trusted, the name po-se-da-wo-ne (“Poseidon”) occurs with greater frequency than does di-u-ja (“Zeus”). A feminine variant, po-se-de-ia, is also found, indicating a lost consort goddess, in effect a precursor of Amphitrite, a sea-goddess and wife of Poseidon. In Roman mythology, the consort of Neptune, a comparatively minor figure, was Salacia, the goddess of saltwater.

In the heavily sea-dependent Mycenaean culture, no connection between Poseidon and the sea has yet surfaced. Homer and Hesiod suggest that Poseidon became lord of the sea following the defeat of his father Kronos, when the world was divided by lot among his three sons; Zeus was given the sky, Hades the underworld, and Poseidon the sea, with the Earth and Mount Olympus belonging to all three.

Given Poseidon’s connection with horses as well as the sea, and the landlocked situation of the likely Indo-European homeland, Nobuo Komita has proposed that Poseidon was originally an aristocratic Indo-European horse-god who was then assimilated to Near Eastern aquatic deities when the basis of the Greek livelihood shifted from the land to the sea, or a god of fresh waters who was assigned a secondary role as god of the sea, where he overwhelmed the original Aegean sea deities such as Proteus and Nereus.

Conversely, Walter Burkert suggests that the Hellene cult worship of Poseidon as a horse god may be connected to the introduction of the horse and war-chariot from Anatolia to Greece around 1600 BC. In any case, the early importance of Poseidon can still be glimpsed in Homer’s Odyssey, where Poseidon rather than Zeus is the major mover of events.

Wanax

Poseidon carries frequently the title wa-na-ka (wanax) in Linear B inscriptions, as king of the underworld, and his title E-ne-si-da-o-ne in Mycenean Knossos and Pylos indicates his chthonic nature , a powerful attribute (earthquakes had accompanied the collapse of the Minoan palace-culture).

Anax is an ancient Greek word for “(tribal) king, lord, (military) leader”. It is one of the two Greek titles traditionally translated as “king”, the other being basileus. Anax is the more archaic term of the two, inherited from the Mycenaean period, and is notably used in Homeric Greek, e.g. of Agamemnon. The feminine form is anassa, “queen” (ánassa; from wánassa, itself from *wánakt-ja).

The word anax derives from the stem wanakt-, and appears in the Mycenaean language, written in Linear B script as, wa-na-ka, and in the feminine form as, wa-na-sa (later ánassa).

The digamma ϝ was pronounced /w/ and was dropped very early on, even before the adoption of the Phoenician alphabet, by eastern Greek dialects (e.g. Ionian); other dialects retained the digamma until well after the classical era.

The word Anax in the Iliad refers to Agamemnon (i.e. “leader of men”) and to Priam, high kings who exercise overlordship over other, presumably lesser, kings. This possible hierarchy of one “anax” exercising power over several local “basileis” probably hints to a proto-feudal political organization of Bronze Age Greece.

The Linear B adjective, wa-na-ka-te-ro (wanákteros), “of the [household of] the king, royal”, and the Greek word ἀνάκτορον, anáktoron, “royal [dwelling], palace” are derived from anax.

Anax is also a ceremonial epithet of the god Zeus (“Zeus Anax”) in his capacity as overlord of the Universe, including the rest of the gods. The meaning of basileus as “king” in Classical Greece is due to a shift in terminology during the Greek Dark Ages.

In Mycenaean times, a *gʷasileus appears to be a lower-ranking official (in one instance a chief of a professional guild), while in Homer, Anax is already an archaic title, most suited to legendary heroes and gods rather than for contemporary kings.

The Greek title has been compared to Sanskrit vanij, a word for “merchant”, but in the Rigveda once used as a title of Indra. The word could then be from Proto-Indo-European *wen-ag’-, roughly “bringer of spoils” (compare the etymology of lord, “giver of bread”).

The word is found as an element in such names as Hipponax (“king of horses”), Anaxagoras (“king of the agora”), Pleistoanax (“king of the multitude”), Anaximander (“king of the estate”), Anaximenes (“enduring king”), Astyanax (“high king”, “overlord of the city”) Anaktoria (“royal [woman]“), Iphiánassa (“mighty queen”), and many others.

The archaic plural Ánakes (“Kings”) was a common reference to the Dioscuri or Heavenly Twins, Castor and Polydeuces, whose temple was usually called the Anakeion and their yearly religious festival the Anákeia.

The words ánax and ánassa are occasionally used in Modern Greek as a deferential to royalty, whereas the word anáktoro[n] and its derivatives are commonly used with regard to palaces.

Anakes

Anakes were ancestral spirits worshipped for their government or religious service in Attica and/or Argos. Titles corresponded to their function on Earth, such as “Son of Zeus.” The clearest symbol of their existence, in Greek Mythology, was the wolf.

Anak/ Anakim

Anak is a well-known figure in the Hebrew Bible in the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites who, according to the Book of Numbers, was a forefather of the Anakim (Heb. Anakim) who have been considered “strong and tall,” they were also said to have been a mixed race of giant people, descendants of the Nephilim (Numbers 13:33).

The use of the word “nephilim” in this verse describes a crossbreed of God’s sons and the daughters of man, as cited in (Genesis 6:1-2) and (Genesis 6:4). The text states that Anak was a Rephaite (Deuteronomy 2:11) and a son of Arba (Joshua 15:13). Etymologically, Anak means [long] neck.

Anakim are a race of giants descended from Anak mentioned in the Tanakh. They dwelt in the south of the land of Canaan, near Hebron (Gen. 23:2; Josh. 15:13). According to Genesis 14:5-6, they inhabited the region afterwards known as Edom and Moab in the days of Abraham. Their name may come from a Hebrew root meaning “strength” or “stature”.

Their formidable appearance, as described by the Twelve Spies sent to search the land, filled the Israelites with terror. The Israelites seem to have identified them with the Nephilim, the giants (Genesis 6:4, Numbers 13:33) of the antediluvian age.

Joshua finally expelled them from the land, excepting a remnant that found a refuge in the cities of Gaza, Gath, and Ashdod (Joshua 11:22). The Philistine giants whom David encountered (2 Samuel 21:15-22) were descendants of the Anakim.

Anak could be related to the Sumerian god Enki. Robert Graves, considering the relationship between the Anakites and Philistia (Joshua 11:21, Jeremiah 47:5), identifies the Anakim with the Greek title Anax, the giant ruler of the Anactorians in Greek mythology.

Nephilim

The Nephilim were offspring of the “sons of God” and the “daughters of men” before the Deluge according to Genesis 6:4; the name is also used in reference to giants who inhabited Canaan at the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan according to Numbers 13:33. A similar biblical Hebrew word with different vowel-sounds is used in Ezekiel 32:27 to refer to dead Philistine warriors.

The Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon gives the meaning of Nephilim as “giants.” Many suggested interpretations are based on the assumption that the word is a derivative of Hebrew verbal root n-ph-l “fall.” Robert Baker Girdlestone argued the word comes from the Hiphil causative stem, implying that the Nephilim are to be perceived as “those that cause others to fall down.” Adam Clarke took it as a perfect participle, “fallen,” “apostates.”

Ronald Hendel states that it is a passive form “ones who have fallen,” equivalent grammatically to paqid “one who is appointed” (i.e., overseer), asir, “one who is bound,” (i.e., prisoner) etc. According to the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon, the basic etymology of the word Nephilim is “dub[ious],” and various suggested interpretations are “all very precarious.”

The majority of ancient biblical versions, including the Septuagint, Theodotion, Latin Vulgate, Samaritan Targum, Targum Onkelos and Targum Neofiti, interpret the word to mean “giants.” Symmachus translates it as “the violent ones” and Aquila’s translation has been interpreted to mean either “the fallen ones” or “the ones falling [upon their enemies].”

Philistines

The Philistines were a people described in the Hebrew Bible. The Hebrew term “pelistim” occurs 286 times in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew bible (of which 152 times in Samuel 1), whereas in the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible, the equivalent term phylistiim occurs only 12 times, with the remaining 269 references instead using the term “allophylos” (“of another tribe”).

According to Joshua 13:3 and 1 Samuel 6:17, the land of the Philistines (or Allophyloi), called Philistia, was a Pentapolis in south-western Levant comprised the five city-states of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath, from Wadi Gaza in the south to the Yarqon River in the north, but with no fixed border to the east. The Bible portrays them at one period of time as among the Kingdom of Israel’s most dangerous enemies.

The origins of the Philistines are not clear and is the subject of considerable speculation. Biblical scholars have connected the Philistines to other biblical groups such as Caphtorim and the Cherethites and Pelethites, which have both been identified with Crete, and leading to the tradition of an Aegean origin, although this theory has been disputed.

Since 1822, scholars have connected the Biblical Philistines with the Egyptian “Peleset” inscriptions, and since 1873, they have both been connected with the Aegean “Pelasgians”. Whilst the evidence for these connections is etymological and has been disputed, this identification is held by the majority of egyptologists and biblical archaeologists.

Biblical archaeology has focused on identifying archaeological evidence for the Philistines. According to Israel Finkelstein, archaeological research to date has been unable to corroborate a mass settlement of Philistines during the Ramesses III era.

Archaeological references in Egyptian texts, and later in Assyrian texts, to “Peleset” or “Palashtu” appear from c.1150 BCE, just as archaeological references to “Kinaḫḫu” or “Ka-na-na” (Canaan) come to an end.

Apkallu

The Apkallu (Akkadian) or Abgal, (Sumerian), from Sumerian AB.GAL.LU (Ab=water, Gal=Great Lu=Man), meaning sage, are seven Sumerian sages, demigods who are said to have been created by the god Enki to establish culture and give civilization to mankind. They served as priests of Enki and as advisors or sages to the earliest kings of Sumer before the flood. They are credited with giving mankind the Me (moral code), the crafts, and the arts. They were seen as fish-like men who emerged from the sweet water Abzu, and are commonly represented as having the lower torso of a fish, or dressed as a fish.

According to the myth, human beings were initially unaware of the benefits of culture and civilization. The god Enki sent from Dilmun, amphibious half-fish, half-human creatures who emerged from the oceans to live with the early human beings and teach them the arts and other aspects of civilization such as writing, law, temple and city building and agriculture. These creatures are known as the Apkallu. The Apkallu remained with human beings after teaching them the ways of civilization, and served as advisors to the kings.

The Apkallus are referred to in several Sumerian myths in cuneiform literature. They are first referred to in the Erra Epic by the character of Marduk who asks “Where are the Seven Sages of the Apsu, the pure puradu fish, who just as their lord Ea, have been endowed with sublime wisdom?” According to the Temple Hymn of Ku’ara, all seven sages are said to have originally belonged to the city of Eridu.

However, the names and order of appearance of these seven sages are varied in different sources. They are also referred to in the incantation series Bit Meseri’s third tablet. In non-cuneiform sources, they find references in the writings of Berossus, the 3rd century BC, Babylonian priest of Bel Marduk.

Berossus describes the appearance from the Persian Gulf of the first of these sages Oannes and describes him as a monster with two heads, the body of a fish and human feet. He then relates that more of these monsters followed. The seven sages are also referred to in an exorcistic text where they are described as bearing the likeness of carps.

These seven were each advisers for seven different kings and therefore result in two different lists, one of kings and one of Apkallu. Neither the sages nor the kings in these lists were genealogically related however.

Apkallu and human beings were presumably capable of conjugal relationships since after the flood, the myth states that four Apkallu appeared. These were part human and part Apkallu, and included Nungalpirriggaldim, Pirriggalnungal, Pirriggalabsu, and Lu-nana who was only two-thirds Apkallu.

Adapa

The apkallu were seven legendary culture heroes from before the Flood, of human descent, but possessing extraordinary wisdom from the gods, and one of the seven apkallu, Adapa, either the first or the last of the Mesopotamian seven sages, was therefore called “son of EA”, despite his human origin.

Adapa was a mythical figure who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BCE), in fragmentary tablets from Tell el-Amarna, and from Assur, of the late second millennium BCE.

Mesopotamian myth tells of seven antediluvian sages, who were sent by Ea, the wise god of Eridu, to bring the arts of civilisation to humankind. The first of these, Adapa, also known as Uan, the name given as Oannes by Berossus, introduced the practice of the correct rites of religious observance as priest of the E’Apsu temple, at Eridu.

Adapa was a mortal man from a godly lineage, a son of Ea (Enki in Sumerian), the god of wisdom and of the ancient city of Eridu, who brought the arts of civilization to that city (from Dilmun, according to some versions). He is often identified as advisor to the mythical first (antediluvian) king of Eridu, Alulim. In addition to his advisory duties, he served as a priest and exorcist, and upon his death took his place among the Seven Sages or Apkallū.

Adapa broke the wings of Ninlil the South Wind, who had overturned his fishing boat, and was called to account before Anu. Ea, his patron god, warned him to apologize humbly for his actions, but not to partake of food or drink while he was in heaven, as it would be the food of death. Anu, impressed by Adapa’s sincerity, offered instead the food of immortality, but Adapa heeded Ea’s advice, refused, and thus missed the chance for immortality that would have been his.

Vague parallels can be drawn to the story of Genesis, where Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden by Yahweh, after they ate from the Tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thus gaining death. Parallels are also apparent (to an even greater degree) with the story of Persephone visiting Hades, who was warned to take nothing from that kingdom.

Stephanie Galley writes “From Erra and Ishum we know that all the sages were banished … because they angered the gods, and went back to the Apsu, where Ea lived, and … the story … ended with Adapa’s banishment” p. 182.

The sages are described in Mesopotamian literature as ‘pure parādu-fish, probably carp, whose bones are found associated with the earliest shrine, and still kept as a holy duty in the precincts of Near Eastern mosques and monasteries.

Adapa as a fisherman was iconographically portrayed as a fish-man composite. The word Abgallu, sage (Ab = water, Gal = great, Lu = man, Sumerian) survived into Nabatean times, around the 1st century, as apkallum, used to describe the profession of a certain kind of priest.

Oannes was the name given by the Babylonian writer Berossus in the 3rd century BCE to a mythical being who taught mankind wisdom. Berossus describes Oannes as having the body of a fish but underneath the figure of a man. He is described as dwelling in the Persian Gulf, and rising out of the waters in the daytime and furnishing mankind instruction in writing, the arts and the various sciences.

The name “Oannes” was once conjectured to be derived from that of the ancient Babylonian god Ea, but it is now known that the name is the Greek form of the Babylonian Uanna (or Uan) a name used for Adapa in texts from the Library of Ashurbanipal. The Assyrian texts attempt to connect the word to the Akkadian for a craftsman ummanu but this is merely a pun.

Haya/Nidaba

Haya’s functions are two-fold: he appears to have served as a door-keeper but was also associated with the scribal arts, and may have had an association with grain. In the god-list AN = dA-nu-um preserved on manuscripts of the first millennium he is mentioned together with dlugal-[ki-sá-a], a divinity associated with door-keepers. Already in the Ur III period Haya had received offerings together with offerings to the “gate”. This was presumably because of the location of one of his shrines.

At least from the Old Babylonian period on he is known as the spouse of the grain-goddess Nidaba/Nissaba (Ops), the Sumerian goddess of grain and writing, patron deity of the city Ereš (Uruk), who is also the patroness of the scribal art.

The intricate connection between agriculture and accounting/writing implied that it was not long before Nidaba became the goddess of writing. From then on her main role was to be the patron of scribes. She was eventually replaced in that function by the god Nabu.

In a debate between Nidaba and Grain, Nidaba is syncretised with Ereškigal (Lua), whose name translates as “Lady of the Great Earth”, “Mistress of the Underworld”. Unlike her consort Nergal, Ereškigal has a distinctly dual association with death. This is reminiscent of the contradictive nature of her sister Inanna/Ištar, who simultaneously represents opposing aspects such as male and female; love and war. In Ereškigal’s case, she is the goddess of death but also associated with birth; regarded both as mother(-earth) and a virgin.

Ereškigal is the sister of Ištar and mother of the goddess Nungal. Namtar, Ereškigal’s minister, is also her son by Enlil; and Ninazu, her son by Gugal-ana. The latter is the first husband of Ereškigal, who in later tradition has Nergal as consort. Bēlet-ṣēri appears as the official scribe for Ereškigal in the Epic of Gilgameš.

With few exceptions Ereškigal had no cult in Mesopotamia and as a result, rarely encountered outside literature. Inscriptions, however, attest to temples of Ereškigal in Kutha, Assur and Umma.

Nidaba is also identified with the goddess of grain Ašnan, and with Nanibgal/Nidaba-ursag/Geme-Dukuga, the throne bearer of Ninlil and wife of Ennugi, throne bearer of Enlil. The Sumerian tale of the Curse of Agade lists Nidaba as belonging to the elite of the great gods.

Nidaba’s spouse is Haya and together they have a daughter, Sud/Ninlil. Traditions vary regarding the genealogy of Nidaba. She appears on separate occasions as the daughter of Enlil, of Uraš, of Ea, and of Anu. Two myths describe the marriage of Sud/Ninlil with Enlil. This implies that Nidaba could be at once the daughter and the mother-in-law of Enlil.

Nidaba is also the sister of Ninsumun, the mother of Gilgameš. Nidaba is frequently mentioned together with the goddess Nanibgal who also appears as an epithet of Nidaba, although most god lists treat her as a distinct goddess.