Draco and Hydra

“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”

A story about the feminine and the masculine powers

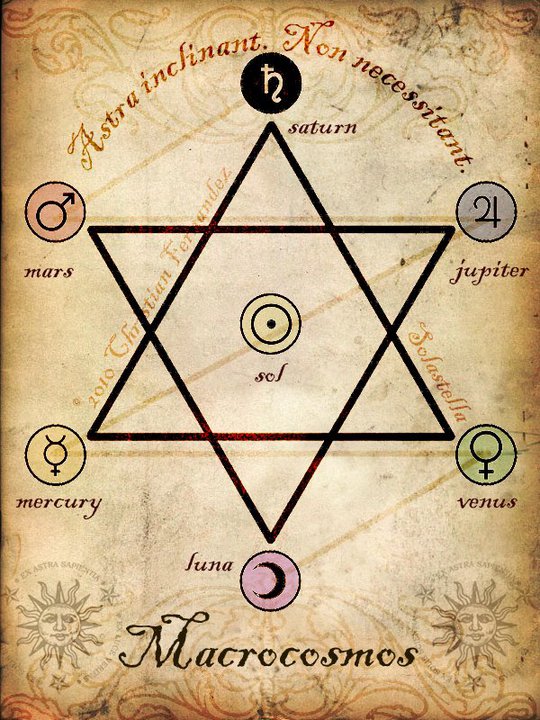

The Sun god that became Mars-Apollo-Pluto (Mars-Sky- Sun) – Pluto is also associated with Tuesday, alongside Mars.

The Sun goddess that became Venus-Neptune (Venus-Earth-Moon) – Neptune also represents the day of Friday, alongside Venus.

In the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively.

An equinox is the moment in which the plane of Earth’s equator passes through the center of the Sun, which occurs twice each year, around 20 March and 23 September.

–

The Equinoxes – Aries-Pisces / Libra-Virgo

Aries (meaning “ram”) is the first astrological sign in the zodiac, spanning the first 30 degrees of celestial longitude (0°≤ λ <30°). Under the tropical zodiac, the Sun transits this sign mostly between March 21 and April 19 each year.

The symbol of the ram is based on the Chrysomallus, the flying ram that provided the Golden Fleece. The fleece is a symbol of authority and kingship.

Libra is the seventh astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans the 180–210th degree of the zodiac, between 180 and 207.25 degree of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac, Sun transits this area on average between (northern autumnal equinox) September 23 and October 22, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun currently transits the constellation of Libra from approximately October 16 to November 17.

The symbol of the scales is based on the Scales of Justice held by Themis, the Greek personification of divine law and custom. She became the inspiration for modern depictions of Lady Justice. The ruling planet of Libra is Venus.

–

The center of the world

Ekur (É.KUR) is a Sumerian term meaning “mountain house”. It is the assembly of the gods in the Garden of the gods, parallel in Greek mythology to Mount Olympus and was the most revered and sacred building of ancient Sumer.

In mythology, the Ekur was the centre of the earth and location where heaven and earth were united. It is also known as Duranki and one of its structures is known as the Kiur (“great place”).

Enamtila, a Sumerian term meaning “house of life” or possibly “house of creation”, has also been suggested by Piotr Michalowski to be a part of the Ekur.

A hymn to Nanna illustrates the close relationship between temples, houses and mountains. “In your house on high, in your beloved house, I will come to live, O Nanna, up above in your cedar perfumed mountain”.

The Ekur was seen as a place of judgement and the place from which Enlil’s divine laws are issued. The ethics and moral values of the site are extolled in myths, which Samuel Noah Kramer suggested would have made it the most ethically-oriented in the entire ancient Near East.

Its rituals are also described as: “banquets and feasts are celebrated from sunrise to sunset” with “festivals, overflowing with milk and cream, are alluring of plan and full of rejoicing”.

The priests of the Ekur festivities are described with en being the high priest, lagar as his associate, mues the leader of incantations and prayers, and guda the priest responsible for decoration. Sacrifices and food offerings were brought by the king, described as “faithful shepherd” or “noble farmer”.

An omphalos is a religious stone artifact, or baetylus. In Greek, the word omphalos means “navel”. In Greek lore, Zeus sent two eagles across the world to meet at its center, the “navel” of the world.

The omphalos was not only an object of Hellenic religious symbolism and world centrality; it was also considered an object of power. Its symbolic references included the uterus, the phallus, and a cup of red wine representing royal blood lines.

Yoni the term ‘yoni’ in Sanskrit means ‘a place of origin’ in general. Brahma-yoni, for example, is Brahmn or the Absolute as the source of creation, representing the goddess Shakti in Hinduism.

Within Shaivism, the sect dedicated to the god Shiva, the yoni symbolises his consort. “Among the Hindus, ShivLing is worshipped as a symbol of the God Shiva” representing him the supreme, formless and omnipresent God.

–

The golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the Works and Days of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first.

Those living in the first Age were ruled by Kronos, after the finish of the first age was the Silver, then the Bronze, after this the Heroic age, with the fifth and current age being Iron.

By extension “Golden Age” denotes a period of primordial peace, harmony, stability, and prosperity. During this age peace and harmony prevailed, people did not have to work to feed themselves, for the earth provided food in abundance.

They lived to a very old age with a youthful appearance, eventually dying peacefully, with spirits living on as “guardians”. Plato in Cratylus recounts the golden race of humans who came first. He clarifies that Hesiod did not mean literally made of gold, but good and noble.

There are analogous concepts in the religious and philosophical traditions of the South Asian subcontinent. For example, the Vedic or ancient Hindu culture saw history as cyclical, composed of yugas with alternating Dark and Golden Ages.

The Kali yuga (Iron Age), Dwapara yuga (Bronze Age), Treta yuga (Silver Age) and Satya yuga (Golden Age) correspond to the four Greek ages. Similar beliefs occur in the ancient Middle East and throughout the ancient world, as well.

In classical Greek mythology the Golden Age was presided over by the leading Titan Cronus. In some version of the myth Astraea also ruled. She lived with men until the end of the Silver Age, but in the Bronze Age, when men became violent and greedy, fled to the stars, where she appears as the constellation Virgo, holding the scales of Justice, or Libra.

European pastoral literary tradition often depicted nymphs and shepherds as living a life of rustic innocence and peace, set in Arcadia, a region of Greece that was the abode and center of worship of their tutelary deity, goat-footed Pan, who dwelt among them.

–

Dingir is a Sumerian word for “god.” Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript “D” as in e.g. DInanna.

The cuneiform sign by itself was originally an ideogram for the Sumerian word an (“sky” or “heaven”); its use was then extended to a logogram for the word diĝir (“god” or goddess) and the supreme deity of the Sumerian pantheon An, and a phonogram for the syllable /an/.

Akkadian took over all these uses and added to them a logographic reading for the native ilum and from that a syllabic reading of /il/. In Hittite orthography, the syllabic value of the sign was again only an.

The concept of “divinity” in Sumerian is closely associated with the heavens, as is evident from the fact that the cuneiform sign doubles as the ideogram for “sky”, and that its original shape is the picture of a star. The original association of “divinity” is thus with “bright” or “shining” hierophanies in the sky.

Anu (Akkadian: DAN, Anu‹m›; Sumerian: AN, from an “sky, heaven”) is the earliest attested sky-father deity. In Sumerian religion, he was also “King of the Gods”, “Lord of the Constellations, Spirits and Demons”, and “Supreme Ruler of the Kingdom of Heaven”, where Anu himself wandered the highest Heavenly Regions.

He was believed to have the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and to have created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the Royal Tiara.

When Enlil rose to equal or surpass An in authority, the functions of the two deities came to some extent to overlap. An was also sometimes equated with Amurru, and, in Seleucid Uruk, with Enmešara and Dumuzi.

Tammuz (Sumerian: Dumuzid (DUMU.ZI(D), “faithful or true son”) is a Sumerian god of food and vegetation. Recent discoveries reconfirm him as an annual life-death-rebirth deity.

The Levantine (“lord”) Adonis, who was drawn into the Greek pantheon, was considered by Joseph Campbell among others to be another counterpart of Tammuz. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is built over a cave that was originally a shrine to Adonis-Tammuz.

Enmesarra, or Enmešarra, in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology is an underworld god of the law. Described as a Sun god, protector of flocks and vegetation, and therefore he has been equated with Nergal. On the other hand, he has been described as an ancestor of Enlil, and it has been claimed that Enlil slew him.

Over time Nergal developed from a war god to a god of the underworld. In the mythology, this occurred when Enlil and Ninlil gave him the underworld. In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal and Allatu/Ereshkigal.

Because he was a god of fire, the desert, and the Underworld and also a god from ancient paganism, later Christian writers sometimes identified Nergal as a demon and even identified him with Satan. According to Collin de Plancy and Johann Weyer, Nergal was depicted as the chief of Hell’s “secret police”, and worked as “an honorary spy in the service of Beelzebub”.

The Luwians originally worshipped the old Proto-Indo-European Sun god Tiwaz. The name of the Proto-Anatolian Sun god can be reconstructed as *Diuod-, which derives from the Proto-Indo-European word *dei- (“shine”, “glow”). This name is cognate with the Greek Zeus, Latin Jupiter, and Norse Tyr.

While Tiwaz (and the related Palaic god Tiyaz) retained a promenant role in the pantheon, the Hittite cognate deity, Šiwat (de) was largely eclipsed by the Sun goddess of Arinna, becoming a god of the day, especially the day of death.

The Sun goddess of Arinna is the chief goddess and wife of the weather god Tarḫunna in Hittite mythology. She protected the Hittite kingdom and was called the “Queen of all lands.” Her cult centre was the sacred city of Arinna. In addition to the Sun goddess of Arinna, the Hittites also worshipped the Sun goddess of the Earth and the Sun god of Heaven.

The Sun goddess of the Earth (Hittite: taknaš dUTU, Luwian: tiyamaššiš Tiwaz) was the Hittite goddess of the underworld. Her Hurrian equivalent was Allani (de) and her Sumerian/Akkadian equivalent was Ereshkigal, both of which had a marked influence on the Hittite goddess from an early date. In the Neo-Hittite period, the Hattian underworld god, Lelwani was also syncretised with her.

In Hittite texts she is referred to as the “Queen of the Underworld”. The Sun goddess of the Earth, as a personification of the chthonic aspects of the Sun, had the task of opening the doors to the Underworld. She was also the source of all evil, impurity, and sickness on Earth. She is mostly attested in curses, oaths, and purification rituals.

In the late Babylonian astral-theological system Nergal is related to the planet Mars. As a fiery god of destruction and war, Nergal doubtless seemed an appropriate choice for the red planet, and he was equated by the Greeks to the war-god Ares (Latin Mars)—hence the current name of the planet.

Amongst the Hurrians and later Hittites Nergal was known as Aplu, a name derived from the Akkadian Apal Enlil, (Apal being the construct state of Aplu) meaning “the son of Enlil”. Aplu may be related with Apaliunas who is considered to be the Hittite reflex of *Apeljōn, an early form of the name Apollo.

Aplu was a Hurrian deity of the plague — bringing it, or, if propitiated, protecting from it — and resembles Apollo Smintheus, “mouse-Apollo” Aplu, it is suggested, comes from the Akkadian Aplu Enlil, meaning “the son of Enlil”, a title that was given to the god Nergal, who was linked to Shamash, Babylonian god of the sun.

Utu (Akkadian rendition of Sumerian dUD “Sun”, Assyro-Babylonian Shamash “Sun”) is the Sun god in Sumerian mythology, the son of the moon god Nanna and the goddess Ningal. Utu is the god of the sun, justice, application of law, and the lord of truth.

Shamash (Akkadian: Šamaš dUD) was the solar deity in ancient Semitic religion, corresponding to the Sumerian god Utu. Shamash was also the god of justice in Babylonia and Assyria.

Dyēus is believed to have been the chief deity in the religious traditions of the prehistoric Proto-Indo-European societies. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in society. In his aspect as a father god, his consort would have been Pltwih Méhter, “earth mother”.

This deity is not directly attested; rather, scholars have reconstructed this deity from the languages and cultures of later Indo-European peoples such as the Greeks, Latins, and Indo-Aryans.

According to this scholarly reconstruction, Dyeus was addressed as Dyeu Ph2ter, literally “sky father” or “shining father”, as reflected in Latin Iūpiter, Diēspiter, possibly Dis Pater and deus pater, Greek Zeu pater, Sanskrit Dyàuṣpítaḥ.

As the pantheons of the individual mythologies related to the Proto-Indo-European religion evolved, attributes of Dyeus seem to have been redistributed to other deities.

In Greek and Roman mythology, Dyeus remained the chief god; however, in Vedic mythology, the etymological continuant of Dyeus became a very abstract god, and his original attributes and dominance over other gods appear to have been transferred to gods such as Agni or Indra.

Rooted in the related but distinct Indo-European word *deiwos is the Latin word for deity, deus. The Latin word is also continued in English divine, “deity”, and the original Germanic word remains visible in “Tuesday” (“Day of Tīwaz”) and Old Norse tívar, which may be continued in the toponym Tiveden (“Wood of the Gods”, or of Týr).

Although some of the more iconic reflexes of Dyeus are storm deities, such as Zeus and Jupiter, this is thought to be a late development exclusive to mediterranean traditions, probably derived from syncretism with canaanite deities and Perkwunos.

The deity’s original domain was over the daylight sky, and indeed reflexes emphasise this connection to light: Istanu (Tiyaz) is a solar deity (though this name may actually refer to a female sun goddess), Helios is often referred to as the “eye of Zeus”, in Romanian paganism the Sun is similarly called “God’s eye” and in Indo-Iranian tradition Surya/Hvare-khshaeta is similarly associated with Ahura Mazda.

Even in Roman tradition, Jupiter often is only associated with diurnal lightning at most, while Summanus is a deity responsible for nocturnal lightning or storms as a whole.

The Luwians originally worshipped the old Proto-Indo-European Sun god Tiwaz. Tiwaz was the descendant of the male Sun god of the Indo-European religion, Dyeus. The name of the Proto-Anatolian Sun god can be reconstructed as *Diuod-, which derives from the Proto-Indo-European word *dei- (“shine”, “glow”).

In Bronze Age texts, Tiwaz is often referred to as “Father” (cuneiform Luwian: tatis Tiwaz) and once as “Great Tiwaz” (cuneiform Luwian: urazza- dUTU-az), and invoked along with the “Father gods” (cuneiform Luwian: tatinzi maššaninzi). His Bronze Age epithet, “Tiwaz of the Oath” (cuneiform Luwian: ḫirutalla- dUTU-az), indicates that he was an oath-god.

Ushas, Sanskrit for “dawn”, is a Vedic deity, and consequently a Hindu deity as well. Ushas is an exalted goddess in the Rig Veda but less prominent in post-Rigvedic texts. She is often spoken of in the plural, “the Dawns.”

She is portrayed as warding off evil spirits of the night, and as a beautifully adorned young woman riding in a golden chariot on her path across the sky. Due to her color she is often identified with the reddish cows, and both are released by Indra from the Vala cave at the beginning of time.

In one recent Hindu interpretation, Sri Aurobindo in his Secret of the Veda, described Ushas as “the medium of the awakening, the activity and the growth of the other gods.

She is the first condition of the Vedic realisation. By her increasing illumination the whole nature of man is clarified; through her [mankind] arrives at the Truth, through her he enjoys [Truth’s] beatitude.”

Sanskrit uṣas is an s-stem, i.e. the genitive case is uṣásas. Ushas is derived from the goddess *h₂ausos-, one of the most important goddesses of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion.

Hausos- is the personification of dawn as a beautiful young woman. Her name is reconstructed as Hausōs or Ausōs (PIE *h₂éwsōs, an s-stem), besides numerous epithets.

Her cognates in other Indo-European pantheons include the Greek goddess Eos, the Roman goddess Aurora, the Lithuanian goddess Austrine, and the English goddess Ēostre, whose name is probably the root of the modern English word “Easter.”

The name *héwsōs is derived from a root *h₂ews- “to shine”, thus translating to “the shining one”. Both the English word east and the Latin auster “south” are from a root cognate adjective *hews-t(e)ro-. Also cognate is aurum “gold”, from *hews-o-m.

Besides the name most amenable to reconstruction, *h₂éwsōs, a number of epithets of the dawn goddess may be reconstructed with some certainty. Among these is *wénh₁os (also an s-stem), whence Sanskrit vanas “loveliness; desire”, used of Uṣas in the Rigveda, and the Latin name Venus and the Norse Vanir.

The name indicates that the goddess was imagined as a beautiful nubile woman, who also had aspects of a love goddess. The love goddess aspect was separated from the personification of dawn in a number of traditions, including Roman Venus vs. Aurora, and Greek Aphrodite vs. Eos.

The name of Aphrodite may still preserve her role as a dawn goddess, etymologized as “she who shines from the foam [ocean]” (from aphros “foam” and deato “to shine”).

J.P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams (1997) have also proposed an etymology based on the connection with the Indo-European dawn goddess, from *h₂ebʰor- “very” and *dʰey- “to shine”. Other epithets include Erigone “early-born” in Greek.

The Italic goddess Mater Matuta “Mother Morning” has been connected to Aurora by Roman authors (Lucretius, Priscianus). Her festival, the Matralia, fell on 11 June, beginning at dawn.

The dawn goddess was also the goddess of spring, involved in the mythology of the Indo-European new year, where the dawn goddess is liberated from imprisonment by a god (reflected in the Rigveda as Indra, in Greek mythology as Dionysus and Cronus).

The abduction and imprisonment of the dawn goddess, and her liberation by a heroic god slaying the dragon who imprisons her, is a central myth of Indo-European religion, reflected in numerous traditions. Most notably, it is the central myth of the Rigveda, a collection of hymns surrounding the Soma rituals dedicated to Indra in the new year celebrations of the early Indo-Aryans.

Aya (or Aja) in Akkadian mythology was a mother goddess, consort of the sun god Shamash. She developed from the Sumerian goddess Sherida, consort of Utu.

Sherida is one of the oldest Mesopotamian gods, attested in inscriptions from pre-Sargonic times, her name (as “Aya”) was a popular personal name during the Ur III period (21st-20th century BCE), making her among the oldest Semitic deities known in the region.

As the Sumerian pantheon formalized, Utu became the primary sun god, and Sherida was syncretized into a subordinate role as an aspect of the sun alongside other less powerful solar deities (c.f. Ninurta) and took on the role of Utu’s consort.

When the Semitic Akkadians moved into Mesopotamia, their pantheon became syncretized to the Sumerian. Inanna to Ishtar, Nanna to Sin, Utu to Shamash, etc. The minor Mesopotamian sun goddess Aya became syncretized into Sherida during this process.

The goddess Aya in this aspect appears to have had wide currency among Semitic peoples, as she is mentioned in god-lists in Ugarit and shows up in personal names in the Bible (Gen 36:24, 2 Sam 3:7, 1 Chr 7:28).

Aya is Akkadian for “dawn”, and by the Akkadian period she was firmly associated with the rising sun and with sexual love and youth. The Babylonians sometimes referred to her as kallatu (the bride), and as such she was known as the wife of Shamash. In fact, she was worshiped as part of a separate-but-attached cult in Shamash’s e-babbar temples in Larsa and Sippar.

By the Neo-Babylonian period at the latest (and possibly much earlier), Shamash and Aya were associated with a practice known as Hasadu, which is loosely translated as a “sacred marriage.”

A room would be set aside with a bed, and on certain occasions the temple statues of Shamash and Aya would be brought together and laid on the bed to ceremonially renew their vows. This ceremony was also practiced by the cults of Marduk with Sarpanitum, Nabu with Tashmetum, and Anu with Antu.

Ishara (išḫara) is an ancient deity of unknown origin from northern modern Syria. She first appeared in Ebla and was incorporated to the Hurrian pantheon from which she found her way to the Hittite pantheon.

The etymology of Ishara is unknown. However, Ishara is the Hittite word for “treaty, binding promise”, also personified as a goddess of the oath. In Hurrian and Semitic traditions, Išḫara is a love goddess, often identified with Ishtar. In Alalah, her name was written with the Akkadogram IŠTAR plus a phonetic complement -ra, as IŠTAR-ra.

Variants of the name appear as Ašḫara (in a treaty of Naram-Sin of Akkad with Hita of Elam) and Ušḫara (in Ugarite texts). In Ebla, there were various logographic spellings involving the sign AMA “mother”.

Ishara is a pre-Hurrian and perhaps pre-Semitic deities, later incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon. From the Hurrian Pantheon, Ishara entered the Hittite pantheon and had her main shrine in Kizzuwatna.

“Ishara first appears in the pre-Sargonic texts from Ebla and then as a goddess of love in Old Akkadian potency-incantations (Biggs). Her main epithet was belet rame, lady of love, which was also applied to Ishtar.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet II, col. v.28) it says: ‘For Ishara the bed is made’ and in Atra-hasis (I 301-304) she is called upon to bless the couple on the honeymoon.”

Ishara was also worshipped within the Hurrian pantheon. She was associated with the underworld. Her astrological embodiment is the constellation Scorpio and she is called the mother of the Sebitti (the Seven Stars).

While she was considered to belong to the entourage of Ishtar, she was invoked to heal the sick (Lebrun). As a goddess, Ishara could inflict severe bodily penalties to oathbreakers.

In this context, she came to be seen as a “goddess of medicine” whose pity was invoked in case of illness. There was even a verb, isharis- “to be afflicted by the illness of Ishara”.

Ama-gi is a Sumerian word. It has been translated as “freedom”, as well as “manumission”, “exemption from debts or obligations”, and “the restoration of persons and property to their original status” including the remission of debts. Other interpretations include a “reversion to a previous state” and release from debt, slavery, taxation or punishment.

The word originates from the noun ama “mother” (sometimes with the enclitic dative case marker ar), and the present participle gi4 “return, restore, put back”, thus literally meaning “returning to mother”.

Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer has identified it as the first known written reference to the concept of freedom. Referring to its literal meaning “return to the mother”, he wrote in 1963 that “we still do not know why this figure of speech came to be used for “freedom.””

The earliest known usage of the word was in the reforms of Urukagina. By the Third Dynasty of Ur, it was used as a legal term for the manumission of individuals. It is related to the Akkadian word anduraāru(m), meaning “freedom”, “exemption” and “release from (debt) slavery”.

*Mitra is the reconstructed Proto-Indo-Iranian name of an Indo-Iranian divinity from which the names and some characteristics of Rigvedic Mitrá and Avestan Mithra derive.

Both Vedic Mitra and Avestan Mithra derive from an Indo-Iranian common noun *mitra-, generally reconstructed to have meant “covenant, treaty, agreement, promise.”

This meaning is preserved in Avestan miθra “covenant.” In Sanskrit and modern Indo-Aryan languages, mitra means “friend,” one of the aspects of bonding and alliance.

In Zoroastrianism, Mithra is a member of the trinity of ahuras, protectors of asha/arta (Sanskrit ऋतम् ṛtaṃ “that which is properly/excellently joined; order, rule; truth” or “[that which is] right”.

Mithra’s standard appellation is “of wide pastures” suggesting omnipresence. Mithra is “truth-speaking, … with a thousand ears, … with ten thousand eyes, high, with full knowledge, strong, sleepless, and ever awake.”

As preserver of covenants, Mithra is also protector and keeper of all aspects of interpersonal relationships, such as friendship and love. Related to his position as protector of truth, Mithra is a judge (ratu), ensuring that individuals who break promises or are not righteous (artavan) are not admitted to paradise.

As also in Indo-Iranian tradition, Mithra is associated with (the divinity of) the sun but originally distinct from it. Mithra is closely associated with the feminine yazata Aredvi Sura Anahita, the hypostasis of knowledge.

In the Vedic religion, Ṛta is the principle of natural order which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it. In the hymns of the Vedas, Ṛta is described as that which is ultimately responsible for the proper functioning of the natural, moral and sacrificial orders.

Asha is the Avestan language term for a concept of cardinal importance to Zoroastrian theology and doctrine. Its Old Persian equivalent is arta-. In Middle Iranian languages the term appears as ard-.

In the moral sphere, aša/arta represents what has been called “the decisive confessional concept of Zoroastrianism.” The opposite of Avestan aša is druj, “lie.” The significance of the term is complex, with a highly nuanced range of meaning. It is commonly summarized in accord with its contextual implications of ‘truth’ and ‘right(eousness)’, ‘order’ and ‘right working’.

The word is also the proper name of the divinity Asha, the Amesha Spenta that is the hypostasis or “genius” of “Truth” or “Righteousness”. In the Younger Avesta, this figure is more commonly referred to as Asha Vahishta (Aša Vahišta, Arta Vahišta), “Best Truth”.

Maat or Ma’at refers to both the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice, and the personification of these concepts as a goddess regulating the stars, seasons, and the actions of both mortals and the deities, who set the order of the universe from chaos at the moment of creation.

Her ideological counterpart was Isfet, an ancient Egyptian term from Egyptian mythology meaning “injustice”, “chaos”, or “violence”; as a verb, “to do evil”, used in philosophy, which was built on a religious, social and political affected dualism.

Astraea, Astrea or Astria (“star-maiden” or “starry night”), in ancient Greek religion, was a daughter of Astraeus and Eos. She was the virgin goddess of innocence and purity and is always associated with the Greek goddess of justice, Dike (daughter of Zeus and Themis and the personification of just judgement).

Astraea, the celestial virgin, was the last of the immortals to live with humans during the Golden Age, one of the old Greek religion’s five deteriorating Ages of Man.

According to Ovid, Astraea abandoned the earth during the Iron Age. Fleeing from the new wickedness of humanity, she ascended to heaven to become the constellation Virgo. The nearby constellation Libra reflected her symbolic association with Dike, who in Latin culture as Justitia is said to preside over the constellation.

According to legend, Astraea will one day come back to Earth, bringing with her the return of the utopian Golden Age of which she was the ambassador.

Filed under: Uncategorized

On the development of the Sun and the Thunder god

The Sun / Lion

Anu (Akkadian: DAN, Anu‹m›; Sumerian: AN, from an “sky, heaven”) is the earliest attested sky-father deity. In Sumerian religion, he was also “King of the Gods”, “Lord of the Constellations, Spirits and Demons”, and “Supreme Ruler of the Kingdom of Heaven”, where Anu himself wandered the highest Heavenly Regions.

He was believed to have the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and to have created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the Royal Tiara. In the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively.

When Enlil rose to equal or surpass An in authority, the functions of the two deities came to some extent to overlap. An was also sometimes equated with Amurru, and, in Seleucid Uruk, with Enmešara and Dumuzi.

Enmesarra, or Enmešarra, in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology is an underworld god of the law. Described as a Sun god, protector of flocks and vegetation, and therefore he has been equated with Nergal. On the other hand, he has been described as an ancestor of Enlil, and it has been claimed that Enlil slew him.

The Bull

Nanna / Sin had a beard made of lapis lazuli and rode on a winged bull. The bull was one of his symbols, through his father, Enlil, “Bull of Heaven”, along with the crescent and the tripod (which may be a lamp-stand).

On cylinder seals, he is represented as an old man with a flowing beard and the crescent symbol. In the astral-theological system he is represented by the number 30 and the moon. This number probably refers to the average number of days (correctly around 29.53) in a lunar month, as measured between successive new moons.

He was also the father of Ishkur, also known as (H)Adad, the storm and rain god in the Northwest Semitic and ancient Mesopotamian religions. Adad was also called “Pidar”, “Rapiu”, “Baal-Zephon”, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram dIM.

The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Set; the Rigvedic god Indra; the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus.

Enki – Capricorn

Enkidu / Adapa

Enki is a god in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

He was the deity of crafts (gašam); mischief; water, seawater, lakewater (a, aba, ab), intelligence (gestú, literally “ear”) and creation (Nudimmud: nu, likeness, dim mud, make beer).

He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki.

Enki was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. His image was a double-helix snake, or the Caduceus, sometimes confused with the Rod of Asclepius used to symbolize medicine. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity dressed in the skin of a carp.

Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40,” occasionally referred to as his “sacred number.”

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”. The Sumerian En is translated as a title equivalent to “lord” and was originally a title given to the High Priest. Ki means “earth”, but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root *hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water.” In Sumerian E-A or E-abzu (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”) has been suggested that was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

It has also been suggested that the original non-anthropomorphic divinity at Eridu was not Enki but Abzu. The emergence of Enki as the divine lover of Ninhursag, and the divine battle between the younger Igigi divinities and Abzu, saw the Abzu, the underground waters of the Aquifer, becoming the place in which the foundations of the temple were built.

On the Adda Seal, Enki is depicted with two streams of water flowing into each of his shoulders: one the Tigris, the other the Euphrates. Alongside him are two trees, symbolizing the male and female aspects of nature. He is shown wearing a flounced skirt and a cone-shaped hat. An eagle descends from above to land upon his outstretched right arm. This portrayal reflects Enki’s role as the god of water, life, and replenishment.

Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground.

Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water'”. This may be a reference to Enki’s hieros gamos or sacred marriage with Ki/Ninhursag (the Earth).

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

His symbols included a goat and a fish, which later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, recognised as the Zodiacal constellation Capricornus. He was accompanied by an attendant Isimud. He was also associated with the planet Mercury in the Sumerian astrological system.

Capricorn is the tenth astrological sign in the zodiac, originating from the constellation of Capricornus. It spans the 270–300th degree of the zodiac, corresponding to celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac, the sun transits this area from December 22 to January 19 each year, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits the constellation of Capricorn from approximately January 16 to February 16.

In astrology, Capricorn is considered an earth sign, negative sign, and one of the four cardinal signs. Capricorn is said to be ruled by the planet Saturn. Its symbol is based on the Sumerians’ primordial god of wisdom and waters, Enki with the head and upper body of a mountain goat, and the lower body and tail of a fish.

The mountain goat part of the symbol depicts ambition, resolute, intelligence, curiosity, but also steadiness, and ability to thrive in inhospitable environments while the fish represents passion, spirituality, intuition, and connection with the soul.

Aries (meaning “ram”) is the first astrological sign in the zodiac, spanning the first 30 degrees of celestial longitude (0°≤ λ <30°). Pisces is the twelfth astrological sign in the Zodiac, originating from the Pisces constellation. It spans the 330° to 360° of the zodiac, between 332.75° and 360° of celestial longitude.

Under the tropical zodiac the sun transits this area on average between February 19 and March 20, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits this area between approximately March 13 and April 13. Inanna was associated with the eastern fish of the last of the zodiacal constellations, Pisces. Her consort Dumuzi was associated with the contiguous first constellation, Aries.

Isimud (also Isinu; Usmû; Usumu (Akkadian)) is a minor god, the messenger of the god, Enki, in Sumerian mythology. In ancient Sumerian artwork, Isimud is easily identifiable due to the fact that he is always depicted with two faces facing in opposite directions in a way that is similar to the ancient Roman god, Janus.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces, since he looks to the future and to the past.

It is conventionally thought that the month of January is named for Janus (Ianuarius), but according to ancient Roman farmers’ almanacs Juno was the tutelary deity of the month. At the kalends of each month the rex sacrorum and the pontifex minor offered a sacrifice to Janus in the curia Calabra, while the regina offered a sow or a she lamb to Juno.

Juno is an ancient Roman goddess, the protector and special counselor of the state. She is a daughter of Saturn and sister (but also the wife) of the chief god Jupiter and the mother of Mars and Vulcan. Juno also looked after the women of Rome.

Her Greek equivalent was Hera. Her Etruscan counterpart was Uni. As the patron goddess of Rome and the Roman Empire, Juno was called Regina (“Queen”) and, together with Jupiter and Minerva, was worshipped as a triad on the Capitol (Juno Capitolina) in Rome.

Juno’s own warlike aspect among the Romans is apparent in her attire. She often appeared sitting pictured with a peacock armed and wearing a goatskin cloak. The traditional depiction of this warlike aspect was assimilated from the Greek goddess Athena, whose goatskin was called the ‘aegis’.

The name Juno was also once thought to be connected to Iove (Jove), originally as Diuno and Diove from *Diovona. At the beginning of the 20th century, a derivation was proposed from iuven- (as in Latin iuvenis, “youth”), through a syncopated form iūn- (as in iūnix, “heifer”, and iūnior, “younger”). This etymology became widely accepted after it was endorsed by Georg Wissowa.

Iuuen- is related to Latin aevum and Greek aion (αιών) through a common Indo-European root referring to a concept of vital energy or “fertile time”. The iuvenis is he who has the fullness of vital force. In some inscriptions Jupiter himself is called Iuuntus, and one of the epithets of Jupiter is Ioviste, a superlative form of iuuen- meaning “the youngest”.

Janus presided over the beginning and ending of conflict, and hence war and peace. The doors of his temple were open in time of war, and closed to mark the peace. As a god of transitions, he had functions pertaining to birth and to journeys and exchange, and in his association with Portunus, a similar harbor and gateway god, he was concerned with travelling, trading and shipping.

In accord with his fundamental character of being the Beginner Janus was considered by Romans the first king of Latium, sometimes along with Camese. He would have received hospitably god Saturn, who, expelled from Heaven by Jupiter, arrived on a ship to the Janiculum.

The liminal character of Janus is though present in the association to the Saturnalia of December, reflecting the strict relationship between the two gods Janus and Saturn and the rather blurred distinction of their stories and symbols.

The Romans regarded Saturn as the original and autochthonous ruler of the Capitolium, and the first king of Latium or even the whole of Italy. At the same time, there was a tradition that Saturn had been an immigrant deity, received by Janus after he was usurped by his son Jupiter (Zeus) and expelled from Greece.

His contradictions—a foreigner with one of Rome’s oldest sanctuaries, and a god of liberation who is kept in fetters most of the year—indicate Saturn’s capacity for obliterating social distinctions.

Roman mythology of the Golden Age of Saturn’s reign differed from the Greek tradition. He arrived in Italy “dethroned and fugitive”, but brought agriculture and civilization and became a king. As the Augustan poet Vergil described it:

“[H]e gathered together the unruly race [of fauns and nymphs] scattered over mountain heights, and gave them laws … . Under his reign were the golden ages men tell of: in such perfect peace he ruled the nations.”

The Winter solstice was thought to occur on 25 December. January 1 was new year day: the day was consecrated to Janus since it was the first of the new year and of the month (kalends) of Janus: the feria had an augural character as Romans believed the beginning of anything was an omen for the whole. Thus on that day it was customary to exchange cheerful words of good wishes.

For the same reason everybody devoted a short time to his usual business, exchanged dates, figs and honey as a token of well wishing and made gifts of coins called strenae. Cakes made of spelt (far) and salt were offered to the god and burnt on the altar. Ovid states that in most ancient times there were no animal sacrifices and gods were propitiated with offerings of spelt and pure salt.

This libum was named ianual and it was probably correspondent to the summanal offered the day before the Summer solstice to god Summanus, which however was sweet being made with flour, honey and milk.

Isimud is featured in the legend of “Inanna and Enki” in which he is the one who greets Inanna upon her arrival to the E-Abzu temple in Eridu. He also is the one who informs Enki that the mes have been stolen. In the myth, Isimud also serves as a messenger, telling Inanna to return the mes to Enki or face the consequences.

In the legend, Isimud plays a similar role to Ninshubur, Inanna’s sukkal. Ninshubur (also known as Ninshubar, Nincubura or Ninšubur) was the sukkal or second-in-command of the goddess Inanna in Sumerian mythology.

Ninshubur, however, was not merely Inanna’s servant. She was also a goddess in her own right and her name can be translated from ancient Sumerian as “Queen of the East.” Much like Iris or Hermes in later Greek mythology, Ninshubur served as a messenger to the other gods.

Ninshubur accompanied Inanna as a vassal and friend throughout Inanna’s many exploits. She helped Inanna fight Enki’s demons after Inanna’s theft of the sacred me. Later, when Inanna became trapped in the Underworld, it was Ninshubur who pleaded with Enki for her mistress’s release.

Ancient Sumerian calcite-alabaster figurine of a male worshipper from sometime between 2500 B.C. and 2250 B.C. The inscription on his right arm states that he is praying to Ninshubur. In the same way that Inanna was associated with the planet Venus, Ninshubur was associated with Mercury, possibly because Venus and Mercury appear together in the sky.

Ninshubur was an important figure in ancient Sumerian mythology and she played an integral role in several myths involving her mistress, the goddess, Inanna. In the Sumerian myth of “Inanna and Enki,” Ninshubur is described as the one who rescues Inanna from the monsters that Enki has sent after her. In this myth, Ninshubur plays a similar role to Isimud, who acts as Enki’s messenger to Inanna.

In the Sumerian myth of Inanna’s descent into the Netherworld, Ninshubur is described as the one who pleads with all of the gods in an effort to persuade them to rescue Inanna from the Netherworld.

In later Akkadian mythology, Ninshubur was syncretized with the male messenger deity Papsukkal, the messenger god in the Akkadian pantheon. He is identified in late Akkadian texts and is known chiefly from the Hellenistic period. His consort is Amasagnul, an Akkadian fertility goddess, and he acts as both messenger and gatekeeper for the rest of the pantheon.

A sanctuary, the E-akkil is identified from the Mesopotamian site of Mkish. Papsukkal was syncretized with Ninshubur, the messenger of the goddess Inanna. Papsukkal was the regent of the tenth month in the Babylonian calendar.

Mercury is a major Roman god, being one of the Dii Consentes within the ancient Roman pantheon. He is the patron god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence (and thus poetry), messages/communication (including divination), travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves; he is also the guide of souls to the underworld. He was considered the son of Maia and Jupiter in Roman mythology.

His name is possibly related to the Latin word merx (“merchandise”; cf. merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages); another possible connection is the Proto-Indo-European root merĝ- for “boundary, border” (cf. Old English “mearc”, Old Norse “mark” and Latin “margō”) and Greek οὖρος (by analogy of Arctūrus), as the “keeper of boundaries,” referring to his role as bridge between the upper and lower worlds.

In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms; both gods share characteristics with the Greek god Hermes. He is often depicted holding the caduceus in his left hand. Similar to his Greek equivalent (Hermes) he was awarded the caduceus by Apollo who handed him a magic wand, which later turned into the caduceus.

Mercury rules over Wednesday. In Romance languages, the word for Wednesday is often similar to Mercury (miercuri in Romanian, mercredi in French, miercoles in Spanish and mercoledì in Italian). Uranus is also associated with Wednesday, alongside Mercury (since Uranus is in the higher octave of Mercury).

The name Wednesday continues Middle English Wednesdei. The name is a calque of the Latin dies Mercurii “day of Mercury”, reflecting the fact that the Germanic god Woden (Wodanaz or Odin) during the Roman era was interpreted as “Germanic Mercury”.

Old English still had wōdnesdæg, which would be continued as *Wodnesday (but Old Frisian has an attested wednesdei). By the early 13th century, the i-mutated form was introduced unetymologically.

The development

–

Enlil (“Lord of the Storm”) is the god of wind, air, earth, and storms. It was the name of a chief deity listed and written about in Mesopotamian religion. In Sumerian religion, Ninlil (“lady of the open field” or “Lady of the Wind”), also called Sud, in Assyrian called Mulliltu, is the consort goddess of Enlil.

Her parentage is variously described. Most commonly she is called the daughter of Haia (god of stores) and Nunbarsegunu (or Ninshebargunnu [a goddess of barley] or Nisaba). Another Akkadian source says she is the daughter of Anu (a.k.a. An) and Antu (Sumerian Ki). Other sources call her a daughter of Anu and Nammu.

She lived in Dilmun with her family. Impregnated by her husband Enlil, who lie with her by the water, she conceived a boy, Nanna/Suen, the future moon god. As punishment Enlil was dispatched to the underworld kingdom of Ereshkigal, where Ninlil joined him.

Enlil impregnated her disguised as the gatekeeper, where upon she gave birth to their son Nergal, god of death. In a similar manner she conceived the underworld god Ninazu when Enlil impregnated her disguised as the man of the river of the nether world, a man-devouring river.

Later Enlil disguised himself as the man of the boat, impregnating her with a fourth deity Enbilulu, god of rivers and canals. All of these act as substitutes for Nanna/Suen to ascend. In some texts Ninlil is also the mother of Ninurta, the heroic god who slew Asag the demon with his mace, Sharur.

After her death, she became the goddess of the wind, like Enlil. She may be the Goddess of the South Wind referred to in the story of Adapa, as her husband Enlil was associated with northerly winter storms. As “Lady Wind” she may be associated with the figure of the Akkadian demon “Lil-itu”, thought to have been the origin of the Hebrew Lilith legend.

Sin or Nanna (Sumerian: DŠEŠ.KI, DNANNA) was the god of the moon in the Mesopotamian mythology of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia. Nanna is a Sumerian deity, the son of Enlil and Ninlil, and became identified with Semitic Sin. The original meaning of the name Nanna is unknown. He was also the father of Ishkur.

The earliest spelling found in Ur and Uruk is DLAK.NA (where NA is to be understood as a phonetic complement). The name of Ur, spelled LAK-32.UNUGKI=URIMKI, is itself derived from the theonym, and means “the abode (UNUG) of Nanna (LAK)”.

The pre-classical sign LAK-32 later collapses with ŠEŠ (the ideogram for “brother”), and the classical Sumerian spelling is DŠEŠ.KI, with the phonetic reading na-an-na. The technical term for the crescent moon could also refer to the deity, DU.SAKAR. Later, the name is spelled logographically as DNANNA.

The Semitic moon god Su’en/Sin is in origin a separate deity from Sumerian Nanna, but from the Akkadian Empire period the two undergo syncretization and are identified. The occasional Assyrian spelling of DNANNA-ar DSu’en-e is due to association with Akkadian na-an-na-ru “illuminator, lamp”, an epitheton of the moon god. The name of the Assyrian moon god Su’en/Sîn is usually spelled as DEN.ZU, or simply with the numeral 30, DXXX.

He is commonly designated as En-zu, which means “lord of wisdom”. During the period (c.2600-2400 BC) that Ur exercised a large measure of supremacy over the Euphrates valley, Sin was naturally regarded as the head of the pantheon.

It is to this period that we must trace such designations of Sin as “father of the gods”, “chief of the gods”, “creator of all things”, and the like. The “wisdom” personified by the moon-god is likewise an expression of the science of astronomy or the practice of astrology, in which the observation of the moon’s phases is an important factor.

His wife was Ningal (“Great Lady”), who bore him Utu/Shamash (“Sun”) and Inanna/Ishtar (the goddess of the planet Venus). The tendency to centralize the powers of the universe leads to the establishment of the doctrine of a triad consisting of Sin/Nanna and his children.

Sin had a beard made of lapis lazuli and rode on a winged bull. The bull was one of his symbols, through his father, Enlil, “Bull of Heaven”, along with the crescent and the tripod (which may be a lamp-stand). On cylinder seals, he is represented as an old man with a flowing beard and the crescent symbol.

In the astral-theological system he is represented by the number 30 and the moon. This number probably refers to the average number of days (correctly around 29.53) in a lunar month, as measured between successive new moons.

An important Sumerian text (“Enlil and Ninlil”) tells of the descent of Enlil and Ninlil, pregnant with Nanna/Sin, into the underworld. There, three “substitutions” are given to allow the ascent of Nanna/Sin. The story shows some similarities to the text known as “The Descent of Inanna”.

Shamash (Akkadian: Šamaš dUD) was the solar deity in ancient Semitic religion, corresponding to the Sumerian god Utu. Shamash was also the god of justice in Babylonia and Assyria.

Both in early and in late inscriptions Shamash is designated as the “offspring of Nannar”; i.e. of the Moon-god, and in an enumeration of the pantheon, Sin generally takes precedence of Shamash. The consort of Shamash was known as Aya. She is, however, rarely mentioned in the inscriptions except in combination with Shamash. She developed from the Sumerian goddess Sherida, consort of Utu.

Sherida is one of the oldest Mesopotamian gods. Attested in inscriptions from pre-Sargonic times her name (as “Aya”) was a popular personal name during the Ur III period (21st-20th century BCE), making her among the oldest Semitic deities known in the region.

As the Sumerian pantheon formalized, Utu became the primary sun god, and Sherida was syncretized into a subordinate role as an aspect of the sun alongside other less powerful solar deities (c.f. Ninurta) and took on the role of Utu’s consort.

When the Semitic Akkadians moved into Mesopotamia, their pantheon became syncretized to the Sumerian. Inanna to Ishtar, Nanna to Sin, Utu to Shamash, etc. The minor Mesopotamian sun goddess Aya became syncretized into Sherida during this process.

Aya is Akkadian for “dawn”, and by the Akkadian period she was firmly associated with the rising sun and with sexual love and youth. The Babylonians sometimes referred to her as kallatu (the bride), and as such she was known as the wife of Shamash. In fact, she was worshiped as part of a separate-but-attached cult in Shamash’s e-babbar temples in Larsa and Sippar.

By the Neo-Babylonian period at the latest (and possibly much earlier), Shamash and Aya were associated with a practice known as Hasadu, which is loosely translated as a “sacred marriage.” A room would be set aside with a bed, and on certain occasions the temple statues of Shamash and Aya would be brought together and laid on the bed to ceremonially renew their vows.

According to the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica the Shamash cults at Sippar and Larsa so overshadowed local Sun-deities elsewhere as to lead to an absorption of the minor deities by the predominating one, in the systematized pantheon these minor Sun-gods become attendants that do his service. In the wake of such syncretism Shamash was usually viewed as the Sun-god in general.

Such are Bunene, spoken of as his chariot driver and whose consort is Atgi-makh, Kettu (“justice”) and Mesharu (“right”), who were then introduced as attendants of Shamash. Other Sun-deities such as Ninurta and Nergal, the patron deities of other important centers, retained their independent existences as certain phases of the Sun, with Ninurta becoming the Sun-god of the morning and spring time and Nergal the Sun-god of the noon and the summer solstice.

Together with Nannar–Sin and Ishtar, Shamash completes another triad by the side of Anu, Enlil and Ea. The three powers Sin, Shamash and Ishtar symbolized three great forces of nature: the Moon, the Sun, and the life-giving force of the earth, respectively.

At times instead of Ishtar we find Adad, the storm-god, associated with Sin and Shamash, and it may be that these two sets of triads represent the doctrines of two different schools of theological thought in Babylonia that were subsequently harmonized by the recognition of a group consisting of all four deities.

Another reference to Shamash is the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. When Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel to slay Humbaba, each morning they pray and make libation to shamash in the direction of the rising Sun for safe travels.

Gilgamesh receives dreams from Shamash, which Enkidu then interprets, and at their battle with Humbaba, it is Shamash’s favor for Gilgamesh that enables them to defeat the monster. Shamash gifted to the hero Gilgamesh three weapons (the axe of mighty heroes, a great sword with a blade that weighs six score pounds and a hilt of thirty pounds and the bow of Anshan).

The attribute most commonly associated with Shamash is justice. Just as the Sun disperses darkness, so Shamash brings wrong and injustice to light. Several centuries before Hammurabi, Ur-Engur of the Ur dynasty (c. 2600 BC) declared that he rendered decisions “according to the just laws of Shamash.”

It was a logical consequence of this conception of the Sun-god that he was regarded also as the one who released the sufferer from the grasp of the demons. The sick man, therefore, appeals to Shamash as the god who can be depended upon to help those who are suffering unjustly.

Shamash is frequently associated with the lion, both in mythology and artistic depictions. In the ancient Canaanite religion, a “son of Baal Shamash”, is known for slaying a lion (the son himself possibly an aspect of the god), and Shamash himself is depicted as a lion in religious iconography.

In Assyro-Babylonian ecclesiastical art the great lion-headed colossi serving as guardians to the temples and palaces seem to symbolise Nergal, just as the bull-headed colossi probably typify Ninurta.

Over time Nergal developed from a war god to a god of the underworld. In the mythology, this occurred when Enlil and Ninlil gave him the underworld. In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal and Allatu/Ereshkigal.

In the religion of ancient Babylon, Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the salt sea, mating with Abzû, the god of fresh water, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation. Depicted as a woman, she represents the beauty of the feminine, depicted as the glistening one. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.

It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos, the first in which Tiamat is a creator goddess, through a “Sacred marriage” between salt and fresh water, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second “Chaoskampf” Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.

Tiamat possessed the Tablet of Destinies and in the primordial battle she gave them to Kingu, the deity she had chosen as her lover and the leader of her host, and who was also one of her children.

The deities gathered in terror, but Anu, replaced later, first by Enlil and, then by Ninurta, and then, in the late version which has survived after the First Dynasty of Babylon, by Marduk, the son of Ea.

First extracting a promise that he would be revered as “king of the gods”, overcame her, armed with the arrows of the winds, a net, a club, and an invincible spear.

Akitu or Akitum (Sumerian: ezen á.ki.tum, akiti-šekinku, á.ki.ti.še.gur.ku, lit. “the barley-cutting”, akiti-šununum, lit. “barley-sowing”; Akkadian: akitu or rêš-šattim, “head of the year”) was a spring festival in ancient Mesopotamia.

The name is from the Sumerian for “barley”, originally marking two festivals celebrating the beginning of each of the two half-years of the Sumerian calendar, marking the sowing of barley in autumn and the cutting of barley in spring. In Babylonian religion it came to be dedicated to Marduk’s victory over Tiamat.

In Mesopotamian religion, Ninurta (“lord of barley”) was a god of law, scribes, farming, and hunting. In Lagash he was identified with the city god Ningirsu. In the early days of Assyriology, the name was often transliterated Ninib or Ninip and he was sometimes analyzed as a solar deity.

Ninurta often appears holding a bow and arrow, a sickle sword, or a mace; the mace, named Sharur, is capable of speech and can take the form of a winged lion, possibly representing an archetype for the later Shedu.

In Nippur, Ninurta was worshiped as part of a triad of deities including his father, Enlil and his mother, Ninlil. In variant mythology, his mother is said to be the harvest goddess Ninhursag. The consort of Ninurta was Ugallu in Nippur and Bau when he was called Ningirsu.

In another legend, Ninurta battles a birdlike monster called Imdugud or Anzû; a Babylonian version relates how the monster steals the Tablet of Destinies—believed to contain the details of fate and the future—from Enlil. Ninurta slays each of the monsters later known as the “Slain Heroes”.

Eventually, Ninurta kills Anzû and returns the Tablet of Destinies to his father Enlil. There are many parallels with both and the story of Marduk, who slew Tiamat and delivered the Tablets of Destiny from Kingu to his father Enki.

Hadad, Adad, Haddad (Akkadian) or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Northwest Semitic and ancient Mesopotamian religions. It was attested in Ebla as “Hadda” in c. 2500 BC. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia, where he became known as the Akkadian or Assyrian-Babylonian god Adad by the Amorites.

Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram dIM. Hadad was also called “Pidar”, “Rapiu”, “Baal-Zephon”, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress.

Hadad was equated with the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Set; the Rigvedic god Indra; the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus.

The Sun goddess of Arinna is the chief goddess and wife of the weather god Tarḫunna in Hittite mythology. She protected the Hittite kingdom and was called the “Queen of all lands.” Her cult centre was the sacred city of Arinna. Tarḫunna or Tarḫuna was the Hittite weather god. He was also referred to as the “Weather god of Heaven” or the “Lord of the Land of Hatti”.

As weather god, Tarḫunna was responsible for the various manifestations of the weather, especially thunder, lightening, rain, clouds, and storms. He ruled over the heavens and the mountains. Thus it was Tarḫunna who decided whether there would be fertile fields and good harvests, or drought and famine and he was treated by the Hittites as the ruler of the gods.

Tarḫunna legitimised the position of the Hittite king, who ruled the land of Hatti in the name of the gods. He watched over the kingdom and the other institutions of the state, but also borders and roads.

As a result of his identification with the Hurrian god Teššup, Tarḫunna is also the partner of Ḫepat (who is syncretised with the Sun goddess of Arinna) and the father of the god Šarruma and the goddesses Allanzu and Kunzišalli.

The god had cognates in most other ancient Anatolian languages. In Hattian, he was called Taru; in Luwian, Tarḫunz (Cuneiform: Tarḫu(wa)nt(a)-, Hieroglyphic: DEUS TONITRUS); in Palaic, Zaparwa; in Lycian, Trqqas/Trqqiz; and in Carian, Trquδe. In the wider Mesopotamian sphere, he was associated with Hadad and Teššup.

The Luwian god Tarḫunz worshipped by the Iron Age Neo-Hittite states was closely related to Tarḫunna, Personal names referring to Tarḫunz, like “Trokondas”, are attested into Roman times.

The Sun goddess of Arinna was originally of Hattian origin and was worshipped by the Hattians at Eštan. The name Ištanu is the Hittite form of the Hattian name Eštan and refers to the Sun goddess of Arinna. One of her Hattian epithets was Wurunšemu (“Mother of the land”).

Earlier scholarship understood Ištanu as the name of the male Sun god of the Heavens, but more recent scholarship has held that the name is only used to refer to the Sun goddess of Arinna. Volker Haas (de), however, still distinguishes between a male Ištanu representing the day-star and a female Wurunšemu who is the Sun goddess of Arinna and spends her nights in the underworld.

From the Hittite Old Kingdom, the Sun goddess of Arinna legitimised the authority of the king, in conjunction with the weather god Tarḫunna. The land belonged to the two deities and the established the king, who would refer to the Sun goddess as “Mother”.

The Hittite Sun Goddess of Arinna identified with Hurrian Goddess Hebat (Eba, Eva). Ḫepat, also transcribed, Khepat, was the mother goddess of the Hurrians, known as “the mother of all living”. She is also a Queen of the deities.

It is thought that Hebat may have had a Southern Mesopotamian origin, being the deification of Kubaba, the founder and first ruler of the Third Dynasty of Kish. In the Hurrian language Ḫepa is the most likely pronunciation of the name of the goddess.

In modern literature the sound /h/ in cuneiform sometimes is transliterated as kh. The name may be transliterated in different versions – Khepat with the feminine ending -t is primarily the Syrian and Ugaritic version.

Hebat is married to Teshub and is the mother of Sarruma and Alanzu, as well mother-in-law of the daughter of the dragon Illuyanka. The mother goddess is likely to have had a later counterpart in the Phrygian goddess Cybele.

Teshub (also written Teshup or Tešup; cuneiform dIM; hieroglyphic Luwian (DEUS) TONITRUS, read as Tarhunzas) was the Hurrian god of sky and storm. Taru was the name of a similar Hattic Storm God, whose mythology and worship as a primary deity continued and evolved through descendant Luwian and Hittite cultures.

In these two, Taru was known as Tarhun / Tarhunt- / Tarhuwant- / Tarhunta, names derived from the Anatolian root *tarh “to defeat, conquer”. Taru/Tarhun/Tarhunt was ultimately assimilated into and identified with the Hurrian Teshub around the time of the religious reforms of Muwatalli II, ruler of the Hittite New Kingdom in the early 13th century BCE.

Jupiter is associated with Thursday, and in Romance languages, the name for Thursday often comes from Jupiter (e.g., joi in Romanian, jeudi in French, jueves in Spanish, and giovedì in Italian). In Norse mythology, Thor is a hammer-wielding god associated with thunder, lightning, storms, oak trees, strength, the protection of mankind and also hallowing and fertility.

The cognate deity in wider Germanic mythology and paganism was known in Old English as Þunor and in Old High German as Donar (runic þonar), stemming from a Common Germanic *Þunraz (meaning “thunder”).

These reforms can generally be categorized as an official incorporation of Hurrian deities into the Hittite pantheon, with a smaller number of important Hurrian gods (like Teshub) being explicitly identified with preexisting major Hittite deities (like Taru). Teshub reappears in the post-Hurrian cultural successor kingdom of Urartu as Tesheba, one of their chief gods; in Urartian art he is depicted standing on a bull.

The Hurrian myth of Teshub’s origin—he was conceived when the god Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his father Anu’s genitals, similarly to the Greek story of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus, which is recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony. Teshub’s brothers are Aranzah (personification of the river Tigris), Ullikummi (stone giant) and Tashmishu.

In the Hurrian schema, Teshub was paired with Hebat the mother goddess; in the Hittite, with the sun goddess Arinniti of Arinna—a cultus of great antiquity which has similarities with the venerated bulls and mothers at Çatalhöyük in the Neolithic era. His son was called Sarruma, the mountain god.

Teshub is depicted holding a triple thunderbolt and a weapon, usually an axe (often double-headed) or mace. The sacred bull common throughout Anatolia was his signature animal, represented by his horned crown or by his steeds Seri and Hurri, who drew his chariot or carried him on their backs.

According to Hittite myths, one of Teshub’s greatest acts was the slaying of the dragon Illuyanka. Myths also exist of his conflict with the sea creature (possibly a snake or serpent) Hedammu.

Puruli (EZEN Puruliyas) was a Hattian spring festival, held at Nerik, dedicated to the earth goddess Hannahanna (Hebat), who is married to a new king. The central ritual of the Puruli festival is dedicated to the destruction of the dragon Illuyanka by the storm god Teshub. The corresponding Assyrian festival is the Akitu of the Enuma Elish. Also compared are the Canaanite Poem of Baal and Psalms 93 and 29.

In addition to the Sun goddess of Arinna, the Hittites also worshipped the Sun goddess of the Earth and the Sun god of Heaven, a Hittite solar deity. He was the second-most worshipped solar deity of the Hittites, after the Sun goddess of Arinna. The Sun god of Heaven was identified with the Hurrian solar deity, Šimige.

From the time of Tudḫaliya III, the Sun god of Heaven was the protector of the Hittite king, indicated by a winged solar disc on the royal seals, and was the god of the kingdom par excellence. From the time of Suppiluliuma I (and probably earlier), the Sun god of Heaven played an important role as the foremost oath god in interstate treaties.

The Sun goddess of the Earth (Hittite: taknaš dUTU, Luwian: tiyamaššiš Tiwaz) was the Hittite goddess of the underworld. The Sun goddess of the Earth, as a personification of the chthonic aspects of the Sun, had the task of opening the doors to the Underworld. She was also the source of all evil, impurity, and sickness on Earth.

In Hittite texts she is referred to as the “Queen of the Underworld” and possesses a palace with a vizier and servants. Her Hurrian equivalent was Allani and her Sumero-Akkadian equivalent was Ereshkigal, both of which had a marked influence on the Hittite goddess from an early date. In the Neo-Hittite period, the Hattian underworld god, Lelwani was also syncretised with her.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Article 0

Dyēus (also *Dyḗus Phtḗr) is believed to have been the chief deity in the religious traditions of the prehistoric Proto-Indo-European societies. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in society. In his aspect as a father god, his consort would have been Pltwih Méhter, “earth mother”.

The Luwians originally worshipped the old Proto-Indo-European Sun god Tiwaz. Tiwaz was the descendant of the male Sun god of the Indo-European religion, Dyeus, who was superseded among the Hittites by the Hattian Sun goddess of Arinna.

In Bronze Age texts, Tiwaz is often referred to as “Father” and once as “Great Tiwaz”, and invoked along with the “Father gods”. His Bronze Age epithet, “Tiwaz of the Oath”, indicates that he was an oath-god.

The Sun goddess of Arinna is the chief goddess and wife of the weather god Tarḫunna in Hittite mythology. She protected the Hittite kingdom and was called the “Queen of all lands.” Her cult centre was the sacred city of Arinna.

In addition to the Sun goddess of Arinna, the Hittites also worshipped the Sun goddess of the Earth and the Sun god of Heaven. The Sun god of Heaven was identified with the Hurrian solar deity, Šimige (de).

While Tiwaz (and the related Palaic god Tiyaz) retained a promenant role in the pantheon, the Hittite cognate deity, Šiwat (de) was largely eclipsed by the Sun goddess of Arinna, becoming a god of the day, especially the day of death.

The Sun goddess of the Earth (Hittite: taknaš dUTU, Luwian: tiyamaššiš Tiwaz) was the Hittite goddess of the underworld. Her Hurrian equivalent was Allani (de) and her Sumerian/Akkadian equivalent was Ereshkigal, both of which had a marked influence on the Hittite goddess from an early date. In the Neo-Hittite period, the Hattian underworld god, Lelwani was also syncretised with her.

In the Hittite and Hurrian religions the Sun goddess of the Earth played an important role in the death cult and was understood to be the ruler of the world of the dead. For the Luwians there is a Bronze Age source which refers to the “Sun god of the Earth” (cuneiform Luwian: tiyamašši- dU-za): “If he is alive, may Tiwaz release him, if he is dead, may the Sun god of the Earth release him”.

Distinguishing the various solar deities in the texts is difficult since most are simply written with the Sumerogram dUTU (Solar deity). As a result, the interpretation of the solar deities remains a subject of debate.

An (Sumerian: AN, from an “sky, heaven”; Akkadian: ANU, Anu‹m›) is the earliest attested sky-father deity. In Sumerian, the designation “An” was used interchangeably with “the heavens” so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted.

The doctrine once established remained an inherent part of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion and led to the more or less complete disassociation of the three gods constituting the triad from their original local limitations.

An intermediate step between Anu viewed as the local deity of Uruk, Enlil as the god of Nippur, and Ea as the god of Eridu is represented by the prominence which each one of the centres associated with the three deities in question must have acquired, and which led to each one absorbing the qualities of other gods so as to give them a controlling position in an organized pantheon.

In the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively.

In Sumerian religion, he was also “King of the Gods”, “Lord of the Constellations, Spirits and Demons”, and “Supreme Ruler of the Kingdom of Heaven”, where Anu himself wandered the highest Heavenly Regions.

He was believed to have the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and to have created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the Royal Tiara. His attendant and vizier was the god Ilabrat.

Ilabrat appears on the clay tablets which contain the legend of “Adapa and the food of life” which seems to explain the origin of death. Adapa, who has earned wisdom but not eternal life, is a son of and temple priest for Ea (Enki) in Eridu, and performs rituals with bread and water.

While Adapa is fishing in a calm sea, suddenly the South Wind rises up and overturns his boat, throwing him into the water. This reference to the ‘South Wind’ may refer to Ninlil, wife of Enlil, who was identified as goddess of the South Wind.

Adapa is enraged, and proceeds to break the ‘wings’ of the South Wind, so for seven days she can not blow the freshness of the sea on the warm earth. Adapa is summoned before the court of Anu in the heavens, and his father Ea advises him not to eat or drink anything placed before him, because he fears that this will be the food and water of death.

Anu, however, is impressed with Adapa and instead offers him the food and water of (eternal) life. However, Adapa follows the advice of Ea, and politely refuses to take any food or drink. This food and water of life offered by Anu would have made Adapa and his descendants immortal.

The Akkadians inherited An as the god of heavens from the Sumerian as Anu-, and in Akkadian cuneiform, the DINGIR character may refer either to Anum or to the Akkadian word for god, ilu-, and consequently had two phonetic values an and il. Hittite cuneiform as adapted from the Old Assyrian kept the an value but abandoned il.

Enlil (Sumerian: dEN.LÍL, “Lord of the Storm”) is the god of wind, air, earth, and storms. It was the name of a chief deity listed and written about in Sumerian religion, and later in Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian), Hittite, Canaanite, and other Mesopotamian clay and stone tablets. Enlil was assimilated to the north “Pole of the Ecliptic”. His sacred number name was 50.

When Enlil rose to equal or surpass An in authority, the functions of the two deities came to some extent to overlap. An was also sometimes equated with Amurru, and, in Seleucid Uruk, with Enmešara and Dumuzi.

Tammuz (Sumerian: Dumuzid (DUMU.ZI(D), “faithful or true son”) is a Sumerian god of food and vegetation, also worshiped in the later Mesopotamian states. Recent discoveries reconfirm him as an annual life-death-rebirth deity.

Enmesarra, or Enmešarra, in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology is an underworld god of the law. Described as a Sun god, protector of flocks and vegetation, and therefore he has been equated with Nergal. On the other hand, he has been described as an ancestor of Enlil, and it has been claimed that Enlil slew him.

Nergal seems to be in part a solar deity, sometimes identified with Shamash, but only representative of a certain phase of the sun. Portrayed in hymns and myths as a god of war and pestilence, Nergal seems to represent the sun of noontime and of the summer solstice that brings destruction, high summer being the dead season in the Mesopotamian annual cycle. He has also been called “the king of sunset”.

Shamash (Akkadian: Šamaš dUD) was the solar deity in ancient Semitic religion, corresponding to the Sumerian god Utu. Shamash was also the god of justice in Babylonia and Assyria.

Both in early and in late inscriptions Shamash is designated as the “offspring of Nannar”; i.e. of the Moon-god, and in an enumeration of the pantheon, Sin generally takes precedence of Shamash.

According to the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica the Shamash cults at Sippar and Larsa so overshadowed local Sun-deities elsewhere as to lead to an absorption of the minor deities by the predominating one. In the wake of such syncretism Shamash was usually viewed as the Sun-god in general.

In the systematized pantheon these minor Sun-gods become attendants that do his service. Such are Bunene, spoken of as his chariot driver and whose consort is Atgi-makh, Kettu (“justice”) and Mesharu (“right”), who were then introduced as attendants of Shamash.

Other Sun-deities such as Ninurta and Nergal, the patron deities of other important centers, retained their independent existences as certain phases of the Sun, with Ninurta becoming the Sun-god of the morning and spring time and Nergal the Sun-god of the noon and the summer solstice.

Over time Nergal developed from a war god to a god of the underworld. In the mythology, this occurred when Enlil and Ninlil gave him the underworld. In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal and Allatu/Ereshkigal.

Because he was a god of fire, the desert, and the Underworld and also a god from ancient paganism, later Christian writers sometimes identified Nergal as a demon and even identified him with Satan. According to Collin de Plancy and Johann Weyer, Nergal was depicted as the chief of Hell’s “secret police”, and worked as “an honorary spy in the service of Beelzebub”.