Three things cannot be long hidden

“I am the alpha and the omega”

Aries and Libra – Alpha and Omega

Mary the virgin (Virgo) and Jesus the fish (Pisces)

The symbol of Libra is a simplified drawing of the setting sun, as it falls at dusk. This is also related to the origin of the letter omega in the Greek alphabet. Omega is the 24th and last letter of the Greek alphabet. In the Greek numeric system, it has a value of 800. The word literally means “great O” (ō mega, mega meaning “great”), as opposed to omicron, which means “little O” (o mikron, micron meaning “little”).

Alpha is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 1. It was derived from the Phoenician and Hebrew letter aleph Aleph – an ox (bull) or leader. The Phoenician letter is derived from an Egyptian hieroglyph depicting an ox’s head. Letters that arose from alpha include the Latin A and the Cyrillic letter А.

As the last letter of the Greek alphabet, Omega is often used to denote the last, the end, or the ultimate limit of a set, in contrast to alpha, the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In English, the noun “alpha” is used as a synonym for “beginning”, or “first” (in a series), reflecting its Greek roots.

Alpha (Α or α) and omega (Ω or ω) is a title of Christ and God in the Book of Revelation. This pair of letters are used as Christian symbols, and are often combined with the Cross, Chi-rho, or other Christian symbols.

The term Alpha and Omega comes from the phrase “I am the alpha and the omega”, an appellation of Jesus in the Book of Revelation (verses 1:8, 21:6, and 22:13). This phrase is interpreted by many Christians to mean that Jesus has existed for all eternity or that God is eternal, as in the additional phrase, “the beginning and the end”.

The ecliptic is the circular path on the celestial sphere that the Sun appears to follow over the course of a year; it is the basis of the ecliptic coordinate system. An equinox is commonly regarded as the moment the plane of Earth’s equator passes through the center of the Sun’s disk, which occurs twice each year, around 20 March and 22-23 September. In other words, it is the point in which the center of the visible sun is directly over the equator.

The equinoxes are the only times when the solar terminator (the “edge” between night and day) is perpendicular to the equator. As a result, the northern and southern hemispheres are equally illuminated. The word comes from Latin aequus, meaning “equal”, and nox, meaning “night”.

The equinoxes, along with solstices, are directly related to the seasons of the year. In the northern hemisphere, the vernal equinox (March) conventionally marks the beginning of spring in most cultures and is considered the start of the New Year, while the autumnal equinox (September) marks the beginning of autumn.

The union of Venus and Mars held greater appeal for poets and philosophers, and the couple were a frequent subject of art. The two standard sex symbols are the Mars symbol (often considered to represent a shield and spear) for male and Venus symbol (often considered to represent a bronze mirror with a handle) for female, derived from astrological symbols, denoting the classical planets Mars and Venus, respectively.

Tao or Dao is a Chinese word signifying ‘way’, ‘path’, ‘route’, ‘road’, ‘choose’, ‘key’ or sometimes more loosely ‘doctrine’, ‘principle’ or ‘holistic science’. Within the context of traditional Chinese philosophy and religion, the Tao is the intuitive knowing of “life” that cannot be grasped full-heartedly as just a concept but is known nonetheless through actual living experience of one’s everyday being.

In Chinese philosophy, yin yang (lit. “dark-bright”, “negative-positive”) describes how seemingly opposite or contrary forces may actually be complementary, interconnected, and interdependent in the natural world, and how they may give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another.

Lingam (Sanskrit word, lit. “sign, symbol or mark”; also linga, Shiva linga), is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu deity Shiva, used for worship in temples, smaller shrines, or as self-manifested natural objects. In traditional Indian society, the linga is seen as a symbol of the energy and potential of Shiva himself.

The lingam is often represented as resting on yoni (Sanskrit word, lit. “origin” or “source”, “vulva”), a symbol of Goddess Durga in Hinduism. Other aconistic representations are yoni (of Shakti) and Shaligram (of Vishnu).

In Sumerian religion, Ninḫursaĝ was a mother goddess of the mountains. She is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the “true and great lady of heaven” (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were “nourished by Ninhursag’s milk”.

Sometimes her hair is depicted in an omega shape and at times she wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders. Frequently she carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

Her symbol, resembling the Greek letter omega, has been depicted in art from approximately 3000 BC, although more generally from the early second millennium BC. It appears on some boundary stones — on the upper tier, indicating her importance.

The omega symbol is associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor, and may represent a stylized womb. The symbol appears on very early imagery from Ancient Egypt. Hathor is at times depicted on a mountain, so it may be that the two goddesses are connected.

Cybele (Phrygian: Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya “Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother”, perhaps “Mountain Mother”) is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations dated to the 6th millennium BC and identified by some as a mother goddess.

She is Phrygia’s only known goddess, and was probably its state deity. Her Phrygian cult was adopted and adapted by Greek colonists of Asia Minor and spread to mainland Greece and its more distant western colonies around the 6th century BC. In Rome, Cybele was known as Magna Mater (“Great Mother”).

Libra is the seventh astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans 180°–210° celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac, Sun transits this area on average between (northern autumnal equinox) September 23 and October 23, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun currently transits the constellation of Libra from approximately October 16 to November 17.

According to the Tropical system of astrology, the Sun enters the sign of Libra when it reaches the southern vernal equinox, which occurs around September 22. The sign of Libra is symbolized by the scales. The symbol of the scales is based on the Scales of Justice held by Themis, the Greek personification of divine law and custom. She became the inspiration for modern depictions of Lady Justice. The ruling planet of Libra is Venus.

According to the Romans in the First Century, Libra was a constellation they idolized. The moon was said to be in Libra when Rome was founded. Everything was balanced under this righteous sign. The Roman writer Manilius once said that Libra was the sign “in which the seasons are balanced”. Both the hours of the day and the hours of the night match each other. Thus why the Romans put so much trust in the “balanced sign”.

Going back to ancient Greek times, Libra the constellation between Virgo and Scorpio used to be over ruled by the constellation of Scorpio. They called the area the Latin word “chelae”, which translated to “the claws” which can help identify the individual stars that make up the full constellation of Libra, since it was so closely identified with the Scorpion constellation in the sky.

In some old descriptions the constellation of Libra is treated as the Scorpion’s claws. Libra was known as the Claws of the Scorpion in Babylonian (zibānītu (compare Arabic zubānā)). The Babylonians called this constellation MUL.GIR.TAB – the ‘Scorpion’, the signs can be literally read as ‘the (creature with) a burning sting’.

Scorpio is the eighth astrological sign in the Zodiac, originating from the constellation of Scorpius. It spans 210°–240° ecliptic longitude. Under the tropical zodiac (most commonly used in Western astrology), the sun transits this area on average from October 23 to November 21. Under the sidereal zodiac (most commonly used in Hindu astrology), the sun is in Scorpio from approximately November 16 to December 15.

In ancient times, Scorpio was associated with the planet Mars. After Pluto was discovered in 1930, it became associated with Scorpio instead. Scorpio is also associated with the Greek deity, Artemis, who is said to have created the constellation Scorpius.

Scorpio is associated with three different animals: the scorpion, the snake, and the eagle (or phoenix). The snake and eagle are related to the nearby constellations of Ophiuchus and Aquila, a constellation on the celestial equator. Its name is Latin for ‘eagle’ and it represents the bird that carried Zeus/Jupiter’s thunderbolts in Greco-Roman mythology.

Ophiuchus is a large constellation located around the celestial equator. Its name is from the Greek Ophioukhos; “serpent-bearer”, and it is commonly represented as a man grasping the snake that is represented by the constellation Serpens. Ophiuchus is one of thirteen constellations that cross the ecliptic. It has therefore been called the “13th sign of the zodiac”. However, this confuses sign with constellation.

There is no evidence of the constellation preceding the classical era, and in Babylonian astronomy, a “Sitting Gods” constellation seems to have been located in the general area of Ophiuchus. To the ancient Greeks, the constellation represented the god Apollo struggling with a huge snake that guarded the Oracle of Delphi.

However, it is proposed that Ophiuchus may in fact be remotely descended from this Babylonian constellation, representing Nirah, a serpent-god who was sometimes depicted with his upper half human but with serpents for legs.

Ishara (išḫara) is an ancient deity of unknown origin from northern modern Syria. She was associated with the underworld. Her astrological embodiment is the constellation Scorpio and she is called the mother of the Sebitti (the Seven Stars).

Ishara is a pre-Hurrian and perhaps pre-Semitic deity, later incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon. Her cult was of considerable importance in Ebla from the mid 3rd millennium. She first appeared in Ebla and was incorporated to the Hurrian pantheon from which she found her way to the Hittite pantheon.

The etymology of Ishara is unknown. In Hurrian and Semitic traditions, Išḫara is a love goddess, often identified with Ishtar. Her main epithet was belet rame, lady of love, which was also applied to Ishtar. Ishara was also worshipped within the Hurrian pantheon.

Variants of the name appear as Ašḫara (in a treaty of Naram-Sin of Akkad with Hita of Elam) and Ušḫara (in Ugarite texts). In Ebla, there were various logographic spellings involving the sign AMA “mother”. In Alalah, her name was written with the Akkadogram IŠTAR plus a phonetic complement -ra, as IŠTAR-ra.

She was invoked to heal the sick. As a goddess, Ishara could inflict severe bodily penalties to oathbreakers, in particular ascites. In this context, she came to be seen as a “goddess of medicine” whose pity was invoked in case of illness. There was even a verb, isharis- “to be afflicted by the illness of Ishara”. Ishara is the Hittite word for “treaty, binding promise”, also personified as a goddess of the oath.

Taurus (Latin for “the Bull”) is the second astrological sign in the present zodiac. It spans the 30–60th degree of the zodiac. The Sun is in the sign of Taurus from about April 20 until about May 21 (Western astrology) (Sidereal astrology).

Taurus was the first sign of the zodiac established among the ancient Mesopotamians – the constellation was listed in the MUL.APIN as GU4.AN.NA, “The Bull of Heaven” and described it as “The Bull in Front” – because it was the constellation through which the sun rose on the vernal equinox at that time.

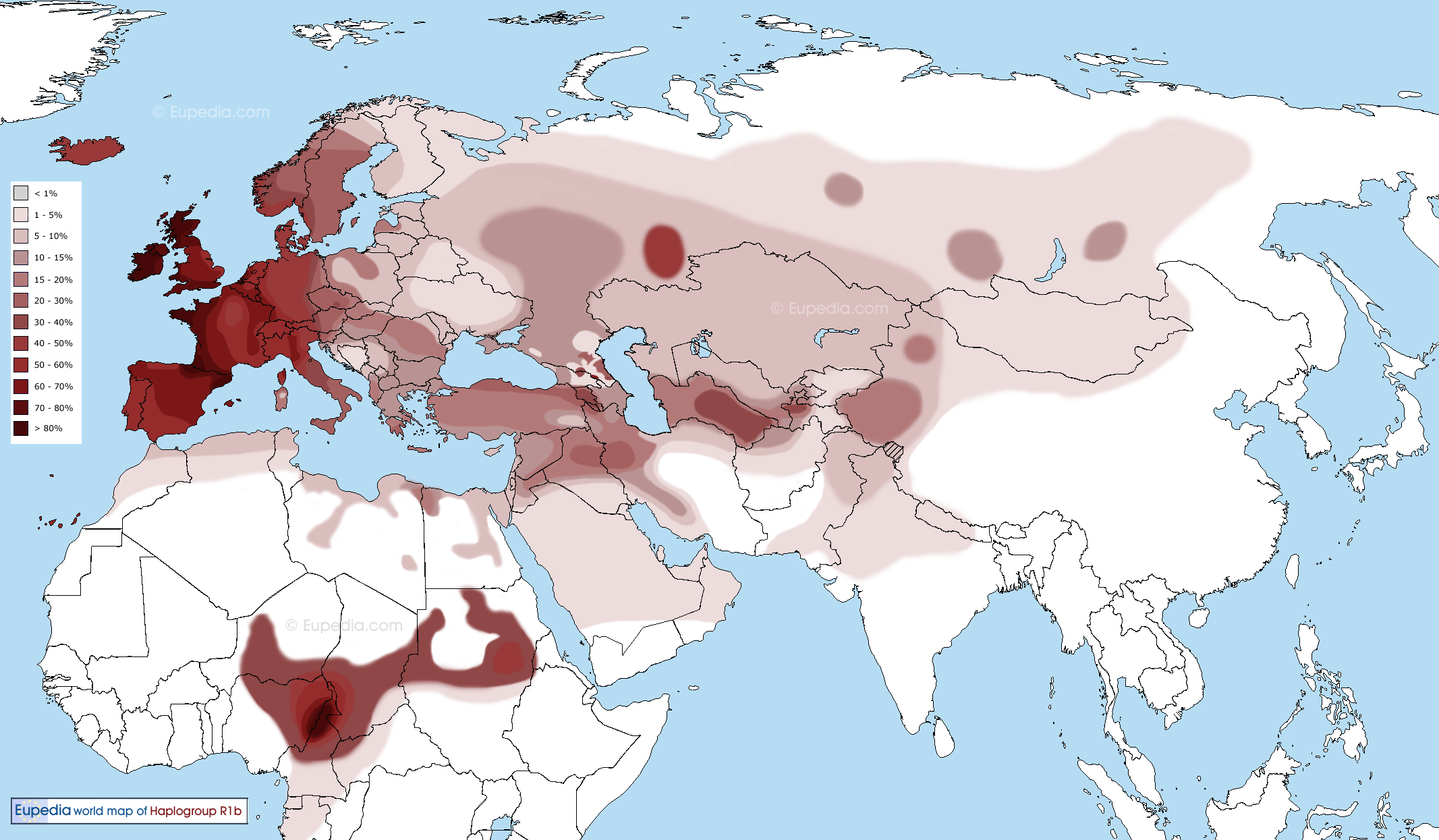

Taurus marked the point of vernal (spring) equinox in the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age, from about 4000 BC to 1700 BC. Due to the precession of the equinox, it has since passed through the neighboring constellation Aries and into the constellation Pisces (hence our current era being known as the Age of Pisces).

The Akkadian name was Alu. To the early Hebrews, Taurus was the first constellation in their zodiac and consequently it was represented by the first letter in their alphabet, Aleph. Alalu is god in Hurrian mythology. He is considered to have housed the divine family, because he was a progenitor of the gods, and possibly the father of Earth.

Alalu was a primeval deity of the Hurrian mythology. After nine years of reign, Alalu was defeated by Anu. Alaluʻs son Kumarbi also defeated Anu, biting and swallowing his genitals, hence becoming pregnant of three gods, among which Teshub who eventually defeated him. Scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

Alalu fled to the underworld. In Akkadian and Sumerian mythology, Alû is a vengeful spirit of the Utukku that goes down to the underworld Kur. In Akkadian and Sumerian mythology, it is associated with other demons like Gallu and Lilu.

The sequence alu (ᚨᛚᚢ) is found in numerous Elder Futhark runic inscriptions of Germanic Iron Age Scandinavia (and more rarely in early Anglo-Saxon England) between the 3rd and the 8th century.

The word usually appears either alone (such as on the Elgesem runestone) or as part of an apparent formula (such as on the Lindholm “amulet” from Scania, Sweden). The symbols represent the runes Ansuz, Laguz, and Uruz.

Scorpius the Scorpion

Scorpius constellation lies in the southern sky. The constellation is easy to find in the sky because it is located near the centre of the Milky Way. The Western astrological sign Scorpio differs from the astronomical constellation. Astronomically, the sun is in Scorpius for just six days, from November 23 to November 28.

The autumn skies are dominated by the enormous figure of the Scorpion. Its array of weaponry has led it to be regarded as a creature symbolising war and the martial prowess of the king. And its venomous nature further expresses the autumnal themes of death and descent to the underworld.

It contains a number of notable stars and deep sky objects, including the bright stars Antares and Shaula, the Butterfly Cluster (Messier 6), the Ptolemy Cluster (Messier 7), Cat’s Paw Nebula (NGC 6334), the Butterfly Nebula (NGC 6302), and the War and Peace Nebula (NGC 6357).

It is one of the twelve members of the zodiac, depicted as a scorpion. Taurus, Leo, Scorpio, and Aquarius occupy and define the zones of the sky that the sun would traverse on the vernal equinox, summer solstice, autumnal equinox, and winter solstice, respectively.

The eagle serves as the astrological equivalent of the scorpion, and thus, the lion, bull, man, and eagle represent the complete cycle of the year, and the four quarters of the earth. In Ezekiel commentaries, it is frequently claimed that the sign of the eagle is equivalent to the scorpion, perhaps because the constellation Aquila the Eagle is in the House of Scorpio. However, the origins of this equivalence are extremely obscure.

It is one of the zodiac constellations, first catalogued by the Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd century. It represents the scorpion and is associated with the story of Orion in Greek mythology.

In Greek mythology, the constellation Scorpius was identified with the scorpion that killed Orion, the mythical hunter. The two constellations lie opposite each other in the sky, and Orion is said to be fleeing from the scorpion as it sets just as Scorpius rises.

In one version of the myth, Orion tried to ravish the goddess Artemis and she sent the scorpion to kill him. In another version, it was the Earth that sent the scorpion after Orion had boasted that he could kill any wild beast.

In ancient Greek times, the constellation Scorpius was significantly larger and comprised of two halves, one with the scorpion’s body and the sting, and one containing the claws. The latter was called Chelae, or “claws” of the Scorpion in Babylonian (zibānītu (compare Arabic zubānā). In the first century BC, the Romans turned the claws into a separate constellation, Libra, the Scales. In some old descriptions the constellation of Libra is treated as the Scorpion’s claws.

However, Scorpius pre-dates the Greeks, and is one of the oldest constellations known. The Sumerians called it GIR-TAB, or “the scorpion,” about 5,000 years ago. The Babylonians called this constellation MUL.GIR.TAB – the ‘Scorpion’, the signs can be literally read as ‘the (creature with) a burning sting’.

One of earliest occurrences of the scorpion in culture is its inclusion, as Scorpio, in the twelve signs of the series of constellations known as the Zodiac by Babylonian astronomers during the Chaldean period.

In ancient Egypt the goddess Serket was often depicted as a scorpion, one of several goddesses who protected the Pharaoh. Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel makes notable symbolic use of scorpions in his 1930 classic L’Age d’or (The Golden Age).

Scorpion I was the first of two rulers of Upper Egypt during Naqada III. His name may refer to the scorpion goddess Serket, though evidence suggests Serket’s rise in popularity to be in the Old Kingdom, bringing doubt to whether Scorpion actually took his name from her. He was one of the first rulers of ancient Egypt.

Scorpion is believed to have lived in Thinis one or two centuries before the rule of the better-known Scorpion II of Nekhen and is presumably the first true king of Upper Egypt. To him belongs the U-j tomb found in the royal cemetery of Abydos where Thinite kings were buried.

Two of those plaques seem to name the towns Baset and Buto, showing that Scorpion’s armies had penetrated the Nile Delta. It may be that the conquests of Scorpion started the Egyptian hieroglyphic system by starting a need to keep records in writing.

Recently a 5,000-year-old graffito has been discovered in the Theban Desert Road Survey that also bears the symbols of Scorpion and depicts his victory over another protodynastic ruler (possibly Naqada’s king). The defeated king or place named in the graffito was “Bull’s Head”, a marking also found in U-j.

Scorpion II (Ancient Egyptian: possibly Selk or Weha), also known as King Scorpion, refers to the second of two kings or chieftains of that name during the Protodynastic Period of Upper Egypt. He ruled one or two centuries after Scorpion I.

The Scorpion macehead (also known as the Major Scorpion macehead) is a decorated ancient Egyptian macehead found in the main deposit in the temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis during the dig season of 1897/1898.

It measures 25 centimeters long, is made of limestone, is pear-shaped, and is attributed to the pharaoh Scorpion due to the glyph of a scorpion engraved close to the image of a king wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt. A second, smaller macehead fragment showing Scorpion wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt is referred to as the Minor Scorpion macehead.

When Scorpio was first described in Sumer, the constellation and the associated region of sky was represented by a scorpion, and this association appears to have persisted in Mesopotamian literature for the next 1500 years.

Scorpion men are featured in several Akkadian language myths, including the Enûma Elish and the Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. They were also known as aqrabuamelu or girtablilu. The Scorpion Men are described to have the head, torso, and arms of a man and the body of a scorpion.

In the religion of ancient Babylon, Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the salt sea, mating with Abzû, the god of fresh water, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation. She creates the Scorpion men in order to wage war against the younger gods for the betrayal of her mate Apsu.

They were said to be guardians of Shamash, the god of Sun truth, justice and healing. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, they stand guard outside the gates of the sun god Shamash at the mountains of Mashu. These give entrance to Kurnugi, the land of darkness. The scorpion men open the doors for Shamash as he travels out each day, and close the doors after him when he returns to the underworld at night.

The people of Mesopotamia invoked the Scorpion People as figures of powerful protection against evil and the forces of chaos. In The Epic of Gilgamesh the Scorpion couple, Scorpion Man and Scorpion Woman, guard the great Gate of the Mountain where the sun rises and are described as `terrifying’.

They also warn travellers of the danger that lies beyond their post. Their heads touch the sky, their “terror is awesome” and their “glance is death”. This meeting of Gilgameš, on his way to Ūta-napišti, with the Scorpion-folk guarding the entrance to the tunnel is described in Iškār Gilgāmeš, tablet IX, lines 47–81.

Ishara (išḫara) is an ancient deity of unknown origin from northern modern Syria. She was associated with the underworld. Her astrological embodiment is the constellation Scorpio and she is called the mother of the Sebitti (the Seven Stars).

Ishara is a pre-Hurrian and perhaps pre-Semitic deity, later incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon. Her cult was of considerable importance in Ebla from the mid 3rd millennium. She first appeared in Ebla and was incorporated to the Hurrian pantheon from which she found her way to the Hittite pantheon.

The etymology of Ishara is unknown. In Hurrian and Semitic traditions, Išḫara is a love goddess, often identified with Ishtar. Her main epithet was belet rame, lady of love, which was also applied to Ishtar. Ishara was also worshipped within the Hurrian pantheon.

Variants of the name appear as Ašḫara (in a treaty of Naram-Sin of Akkad with Hita of Elam) and Ušḫara (in Ugarite texts). In Ebla, there were various logographic spellings involving the sign AMA “mother”. In Alalah, her name was written with the Akkadogram IŠTAR plus a phonetic complement -ra, as IŠTAR-ra.

She was invoked to heal the sick. As a goddess, Ishara could inflict severe bodily penalties to oathbreakers, in particular ascites. In this context, she came to be seen as a “goddess of medicine” whose pity was invoked in case of illness. There was even a verb, isharis- “to be afflicted by the illness of Ishara”. Ishara is the Hittite word for “treaty, binding promise”, also personified as a goddess of the oath.

Sherida is one of the oldest Mesopotamian gods, attested in inscriptions from pre-Sargonic times, her name (as “Aya”) was a popular personal name during the Ur III period (21st-20th century BCE), making her among the oldest Semitic deities known in the region.

As the Sumerian pantheon formalized, Utu became the primary sun god, and Sherida was syncretized into a subordinate role as an aspect of the sun alongside other less powerful solar deities (c.f. Ninurta) and took on the role of Utu’s consort.

When the Semitic Akkadians moved into Mesopotamia, their pantheon became syncretized to the Sumerian. Inanna to Ishtar, Nanna to Sin, Utu to Shamash, etc. The minor Mesopotamian sun goddess Aya became syncretized into Sherida during this process.

The goddess Aya in this aspect appears to have had wide currency among Semitic peoples, as she is mentioned in god-lists in Ugarit and shows up in personal names in the Bible. Aya is Akkadian for “dawn”, and by the Akkadian period she was firmly associated with the rising sun and with sexual love and youth.

The Babylonians sometimes referred to her as kallatu (the bride), and as such she was known as the wife of Shamash. By the Neo-Babylonian period at the latest (and possibly much earlier), Shamash and Aya were associated with a practice known as Hasadu, which is loosely translated as a “sacred marriage.”

A room would be set aside with a bed, and on certain occasions the temple statues of Shamash and Aya would be brought together and laid on the bed to ceremonially renew their vows. This ceremony was also practiced by the cults of Marduk with Sarpanitum, Nabu with Tashmetum, and Anu with Antu.

The gods and the planets

The name “Sunday”, the day of the Sun, is derived from Hellenistic astrology, where the seven planets, known in English as Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and the Moon, each had an hour of the day assigned to them, and the planet which was regent during the first hour of any day of the week gave its name to that day.

During the 1st and 2nd century, the week of seven days was introduced into Rome from Egypt, and the Roman names of the planets were given to each successive day. Germanic peoples seem to have adopted the week as a division of time from the Romans, but they changed the Roman names into those of corresponding Teutonic deities. Hence, the dies Solis became Sunday (German, Sonntag).

The Latin name dies Martis (“day of Mars”) is equivalent to Tuesday. The Latin name dies Mercurii “day of Mercury” is equivalent to Wednesday. In Latin, thursday was known as Iovis Dies, “Jupiter’s Day”. The Romans named Saturday Sāturni diēs (“Saturn’s Day”).

Hurrian Mythology

Alalu, Anu, Kumarbi and Teshub

Kumarbi is the chief god of the Hurrians. He is the son of Anu (the sky), and father of the storm-god Teshub. He was identified by the Hurrians with Sumerian Enlil, and by the Ugaritians with El.

Kumarbi is known from a number of mythological Hittite texts, sometimes summarized under the term “Kumarbi Cycle”. These texts notably include the myth of The Kingship in Heaven (also known as the Song of Kumarbi, or the “Hittite Theogony”.

The Song of Kumarbi or Kingship in Heaven is the title given to a Hittite version of the Hurrian Kumarbi myth, dating to the 14th or 13th century BC. It is preserved in three tablets, but only a small fraction of the text is legible.

The song relates that Alalu was overthrown by Anu who was in turn overthrown by Kumarbi. When Anu tried to escape, Kumarbi bit off his genitals and spat out three new gods.

In the text Anu tells his son that he is now pregnant with the Teshub, Tigris, and Tašmišu. Upon hearing this Kumarbi spit the semen upon the ground and it became impregnated with two children. Kumarbi is cut open to deliver Tešub. Together, Anu and Teshub depose Kumarbi.

In another version of the Kingship in Heaven, the three gods, Alalu, Anu, and Kumarbi, rule heaven, each serving the one who precedes him in the nine-year reign. It is Kumarbi’s son Tešub, the Weather-God, who begins to conspire to overthrow his father.

From the first publication of the Kingship in Heaven tablets scholars have pointed out the similarities between the Hurrian creation myth and the story from Greek mythology of Uranus, Cronus, and Zeus.

The Theogony

Uranus / Caelus

The Theogony (i.e. “the genealogy or birth of the gods”) is a poem by Hesiod (8th – 7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed c. 700 BC. It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek.

Uranus (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. His name in Roman mythology was Caelus (compare caelum, the Latin word for “sky” or “the heavens”, hence English “celestial”). In Hesiod’s Theogony, Uranus is the offspring of Gaia, the earth goddess. Uranus was the brother of Pontus, the God of the sea.

One of the principal components of the Theogony is the presentation of the “Succession Myth”. It tells how Cronus overthrew Uranus, and how in turn Zeus overthrew Cronus and his fellow Titans, and how Zeus was eventually established as the final and permanent ruler of the cosmos.

Cronus / Saturn

In the Olympian creation myth, as Hesiod tells it in the Theogony, Uranus came every night to cover the earth and mate with Gaia, but he hated the children she bore him. Uranus imprisoned Gaia’s youngest children in Tartarus, deep within Earth, where they caused pain to Gaia.

Gaia shaped a great flint-bladed sickle and asked her sons to castrate Uranus. Only Cronus, youngest and most ambitious of the Titans, was willing: he ambushed his father and castrated him, casting the severed testicles into the sea. He overthrew his father and ruled during the mythological Golden Age, until he was overthrown by his own son Zeus and imprisoned in Tartarus.

Cronus was usually depicted with a harpe, scythe or a sickle, which was the instrument he used to castrate and depose Uranus, his father. In Athens, on the twelfth day of the Attic month of Hekatombaion, a festival called Kronia was held in honour of Cronus to celebrate the harvest, suggesting that, as a result of his association with the virtuous Golden Age, Cronus continued to preside as a patron of the harvest. Cronus was also identified in classical antiquity with the Roman deity Saturn.

After Uranus was deposed, Cronus re-imprisoned the Hekatonkheires and Cyclopes in Tartarus. Uranus and Gaia then prophesied that Cronus in turn was destined to be overthrown by his own son, and so the Titan attempted to avoid this fate by devouring his young.

Zeus / Jupiter

Zeus, Poseidon and Hades

Zeus, through deception by his mother Rhea, avoided this fate. When Zeus was about to be born, Rhea sought Gaia to devise a plan to save him, so that Cronus would get his retribution for his acts against Uranus and his own children.

Rhea secretly gave birth to Zeus in Crete, and handed Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, also known as the Omphalos Stone, which he promptly swallowed, thinking that it was his last child. The Romans regarded Jupiter as the equivalent of the Greek Zeus.

Zeus was raised by a nurse named Amalthea. Since Cronus ruled over the Earth, the heavens and the sea, she hid him by dangling him on a rope from a tree so he was suspended between earth, sea and sky and thus, invisible to his father.

Throughout history Zeus has used violence to get his way, or even terrorize humans. As God of the sky he has the power to hurl lightning bolts as his weapon of choice. Since lightning is quite powerful and sometimes deadly, it is a bold sign when lightning strikes because it is known that Zeus most likely threw the bolt.

Neptune was the god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune was the brother of Jupiter and Pluto; the brothers presided over the realms of Heaven, the earthly world, and the Underworld.

In Greek mythology, Hades was regarded as the oldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although the last son regurgitated by his father. He and his brothers Zeus and Poseidon defeated their father’s generation of gods, the Titans, and claimed rulership over the cosmos. Hades received the underworld, Zeus the sky, and Poseidon the sea, with the solid earth—long the province of Gaia—available to all three concurrently.

Pluto

Dis Pater / Dyeus

Pluto (Greek: Ploutōn) was the ruler of the underworld in classical mythology. The earlier name for the god was Hades, which became more common as the name of the underworld itself.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Pluto represents a more positive concept of the god who presides over the afterlife. Ploutōn was frequently conflated with Ploutos (Plutus), a god of wealth, because mineral wealth was found underground, and because as a chthonic god Pluto ruled the deep earth that contained the seeds necessary for a bountiful harvest.

The name Ploutōn came into widespread usage with the Eleusinian Mysteries, in which Pluto was venerated as a stern ruler but the loving husband of Persephone. The couple received souls in the afterlife, and are invoked together in religious inscriptions. Hades, by contrast, had few temples and religious practices associated with him, and he is portrayed as the dark and violent abductor of Persephone.

In Greek cosmogony, Pluto received the rule of the underworld in a three-way division of sovereignty over the world, with his brother Zeus ruling the Sky and his other brother Poseidon sovereign over the Sea.

Plūtō is the Latinized form of the Greek Plouton. Pluto’s Roman equivalent is Dis Pater, a Roman god of the underworld, whose name is most often taken to mean “Rich Father” and is perhaps a direct translation of Plouton.

Originally a chthonic god of riches, fertile agricultural land, and underground mineral wealth, Dis Pater was later commonly equated with the Roman deities Pluto and Orcus, becoming an underworld deity.

Dyēus (also *Dyḗus Phtḗr , alternatively spelled dyēws) is believed to have been the chief deity in the religious traditions of the prehistoric Proto-Indo-European societies. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in society.

This deity is not directly attested; rather, scholars have reconstructed this deity from the languages and cultures of later Indo-European peoples such as the Greeks, Latins, and Indo-Aryans.

According to this scholarly reconstruction, Dyeus was known as Dyeus Phter, literally “sky father” or “shining father”, as reflected in Latin Iūpiter, Diēspiter, possibly Dis Pater and deus pater, Greek Zeu pater, Sanskrit Dyàuṣpítaḥ.

As the pantheons of the individual mythologies related to the Proto-Indo-European religion evolved, attributes of Dyeus seem to have been redistributed to other deities. However, in Greek and Roman mythology, Dyeus remained the chief god.

Ares / Mars

Ares is the Greek god of war. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. The counterpart of Ares among the Roman gods is Mars, who as a father of the Roman people was given a more important and dignified place in ancient Roman religion as a guardian deity.

His love affair with Venus symbolically reconciled the two different traditions of Rome’s founding; Venus was the divine mother of the hero Aeneas, celebrated as the Trojan refugee who “founded” Rome several generations before Romulus laid out the city walls.

Although Ares was viewed primarily as a destructive and destabilizing force, Mars represented military power as a way to secure peace, and was a father (pater) of the Roman people. In the mythic genealogy and founding myths of Rome, Mars was the father of Romulus and Remus with Rhea Silvia.

Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him (Latin Martius), and in October, which began the season for military campaigning and ended the season for farming.

The spear is the instrument of Mars in the same way that Jupiter wields the lightning bolt, Neptune the trident, and Saturn the scythe or sickle. A relic or fetish called the spear of Mars was kept in a sacrarium at the Regia, the former residence of the Kings of Rome.

Like Ares who was the son of Zeus and Hera, Mars is usually considered to be the son of Jupiter and Juno. However, in a version of his birth given by Ovid, he was the son of Juno alone. Jupiter had usurped the mother’s function when he gave birth to Minerva directly from his forehead (or mind); to restore the balance, Juno sought the advice of the goddess Flora on how to do the same.

Flora obtained a magic flower (Latin flos, plural flores, a masculine word) and tested it on a heifer who became fecund at once. She then plucked a flower ritually using her thumb, touched Juno’s belly, and impregnated her. Juno withdrew to Thrace and the shore of Marmara for the birth.

The consort of Mars was Nerio or Neriene, an ancient war goddess and the personification of valor. She represents the vital force (vis), power (potentia) and majesty (maiestas) of Mars. Her name was regarded as Sabine in origin and is equivalent to Latin virtus, “manly virtue” (from vir, “man”). A source from late antiquity says that Mars and Neriene were celebrated together at a festival held on March 23. In the later Roman Empire, Neriene came to be identified with Minerva.

Hermes / Mercury

Hermes is an Olympian god in Greek religion and mythology, the son of Zeus and the Pleiad Maia, and the second youngest of the Olympian gods (Dionysus being the youngest). In the Roman adaptation of the Greek pantheon, Hermes is identified with the Roman god Mercury, who, though inherited from the Etruscans, developed many similar characteristics such as being the patron of commerce.

Mercury is a major god in Roman religion and mythology, being one of the Dii Consentes within the ancient Roman pantheon. He is the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence (and thus poetry), messages, communication (including divination), travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves; he also serves as the guide of souls to the underworld. He was considered the son of Maia, who was a daughter of the Titan Atlas, and Jupiter in Roman mythology.

Neptune, Poseidon and Heimdall

Heimdall

(D)Algiz rune – Heimdall

(D)Algiz (also Elhaz) and (T)Yr rune

In Norse mythology, Heimdall’s role is guardian and protector. He is the watcher at the gate who guards the boundaries between the worlds and who charges all those entering and leaving with caution. He is best known for his horn, but his sword is just as important as it can be used for either offence or defence, depending upon the situation.

Heimdallr also appears as Heimdalr and Heimdali. The etymology of the name is obscure, but ‘the one who illuminates the world’ has been proposed. The prefix Heim- means world, the affix -dallr is of uncertain origin, perhaps it means pole (Yggdrasil), perhaps bright – He is described as “the brightest of the gods”.

Scholars have produced various theories about the nature of the god, including his apparent relation to rams, that he may be a personification of or connected to the world tree Yggdrasil, and potential Indo-European cognates.

He was known also by two other names – Hallinskidi and Gullintanni. Heimdall was the warder of the entrance to Asgard: the rainbow bridge called Bifröst (Bifrost or Bilrost). He dwelled in his hall Himinbjörg (Himinbiorg – “Cliff of the Hills” or “Heavenly Fall”), at the edge of Asgard, near Bifröst.

Heimdall had super-sharp eyesight and hearing. He was the never-sleeping watchman, whose duties to prevent giants from entering Asgard. His sword was called Heimdall’s Head (Hofund). He also watched and possessed the horn called Gjallahorn. When Heimdall blows Gjallahorn, it would to signify and warn the other gods of the coming of Ragnarök (Ragnarok).

Heimdall was the son of the Nine Waves (nine giantesses, who were sisters; this mean that Heimdall had nine mothers). The Nine Waves were the nine daughters of Aegir. The Nine mothers are the nine waves of the ocean, pictured as “ewes”, and the Heimdall is “the ram”, the ninth wave. Heimdall’s horn is part of that image, apparently, and he is pictured as either the father of the nine waves or as the child of the nine waves, or both.

Heimdall created the three races of mankind: the serfs, the peasants, and the warriors. It is interesting to note why Heimdall fathered them, and not Odin as might be expected. Furthermore, Heimdall is in many attributes identical with Tyr. As Heimdall, the world tree reach from the sky to the underworld so do Nergal (Tyr) as a skylord, but at the same time a god of the underworld.

Algiz rune

Algiz (also Elhaz) is the name conventionally given to the “z-rune” ᛉ of the Elder Futhark runic alphabet. Its transliteration is z, understood as a phoneme of the Proto-Germanic language, the terminal *z continuing Proto-Indo-European terminal *s. Usualy a long “Z”, as in “buzz” is the pronunciation of this rune, but occasionally “R”, or even “M”, although there are other runes that represent these sounds too.

In the physical world, Algiz is a weapon of protection such as a sword, protecting with a sharp edge. In the spiritual world, Algiz represents a faith or belief in the gods or a god and that which is beyond our five physical senses.

The form of the rune resembles an outstretched hand, probably representing the hand of Tyr, which was sacrificed for the safety of the universe. Algiz represents the divine plan as set apart from individual affairs, even in spite of human concerns entirely.

Algiz (also called Elhaz) is a powerful rune, because it represents the divine might of the universe. The white elk was a symbol to the Norse of divine blessing and protection to those it graced with sight of itself.

Algiz is the rune of higher vibrations, the divine plan and higher spiritual awareness. The energy of Algiz is what makes something feel sacred as opposed to mundane. It represents the worlds of Asgard (gods of the Aesir), Ljusalfheim (The Light Elves) and Vanaheim (gods of the Vanir), all connecting and sharing energies with our world, Midgard.

The rune is a ward of protection, a shield against negativity. The urge to defend or protect others, a guardianship, that banishing or warding off of a negative presence. Opening the pathways to connection to the gods, an awakening. A sign to follow your instincts to keep hold of a position earned.

It represents your power to protect yourself and those around you. It also connotes the thrill and joy of a successful hunt. You are in a very enviable position right now, because you are able to maintain what you have built and reach your current goals.

The symbol itself could represent the upper branches of Yggdrasil, a flower opening to receive the sun (Sowilo is the next rune in the futhark after all,) the antlers of the elk (the elk-sedge), the Valkyrie and her wings, or the invoker stance common to many of the world’s priests and shamans.

It also looks like the outstreched branches of a tree or the footprint of a bird, such as a crow or raven. In a very contemporary context, the symbol could be powerfully equated to a satellite dish reaching toward the heavens and communicating with the gods and other entities throughout this and other worlds.

Algiz is the supreme rune of healing and protection. The upright position of this rune was used to denote the date of birth on Viking tombstones. The inverted form was likewise used to give the date of death.

Protection, a shield. The protective urge to shelter oneself or others. Defense, warding off of evil, shield, guardian. Connection with the gods, awakening, higher life. It can be used to channel energies appropriately. Follow your instincts. Keep hold of success or maintain a position won or earned. Algiz Reversed: or Merkstave: Hidden danger, consumption by divine forces, loss of divine link. Taboo, warning, turning away, that which repels.

When Algiz appears in a reading merkstave, it is a warning to proceed with caution and to not act rashly or hastily. You may be vulnerable to hostile influences at this time and need to concentrate on building your strength physically, emotionally and spiritually before moving forward.

Reversed, Algiz is a sign that hidden dangers lie ahead. Ill-health may be about to strike. It may also represent a warning to get a second (or third) opinion before proceeding with anything of importance (eg. signing contracts etc).

Because this specific phoneme was lost at an early time, the Elder Futhark rune underwent changes in the medieval runic alphabets. In the Anglo-Saxon futhorc it retained its shape, but it was given the sound value of Latin x.

The name of the Anglo-Saxon rune ᛉ is variously recorded as eolx, ilcs, ilix, elux, eolhx. Manuscript tradition gives its sound value as Latin x, i.e. /ks/, or alternatively as il, or yet again as “l and x”.

This is a secondary development, possibly due to runic manuscript tradition, and there is no known instance of the rune being used in an Old English inscription. In Proto-Norse and Old Norse, the Germanic *z phoneme developed into an R sound, perhaps realized as a retroflex approximant [ɻ], which is usually transcribed as ʀ.

In the earliest inscriptions, the rune invariably has its standard Ψ-shape. From the 5th century or so, the rune appears optionally in its upside-down variant which would become the standard Younger Futhark yr shape.

There are also other graphical variants; for example, the Charnay Fibula has a superposition of these two variants, resulting in an “asterisk” shape (ᛯ). The 9th-century abecedarium anguliscum in Codex Sangallensis 878 shows eolh as a peculiar shape, as it were a bindrune of the older ᛉ with the Younger Futhark ᛦ, resulting in an “asterisk” shape similar to ior ᛡ.

The shape of the rune may be derived from that a letter expressing /x/ in certain Old Italic alphabets (𐌙), which was in turn derived from the Greek letter Ψ, which had the value of /kʰ/ (rather than /ps/) in the Western Greek alphabet.

The Elder Futhark rune ᛉ is conventionally called Algiz or Elhaz, from the Common Germanic word for “elk”. However, it is suggested that the original name of the rune could have been Common Germanic *algiz (‘Algie’), meaning not “elk” but “protection, defence”.

Manuscript tradition gives its sound value as Latin x, i.e. /ks/, or alternatively as il, or yet again as “l and x”. It has benn suggested that the eolhx (etc.) may have been a corruption of helix, and that the name of the rune may be connected to the use of elux for helix to describe the constellation of Ursa major (as turning around the celestial pole).

An earlier suggestion is that the earliest value of this rune was the labiovelar /hw/, and that its name may have been hweol “wheel”. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the Elder Futhark began to be replaced by the Younger Futhark in Scandinavia. By the 8th century, the Elder Futhark was extinct, and Scandinavian runic inscriptions were exclusively written in Younger Futhark.

The sound was written in the Younger Futhark using the Yr rune ᛦ, the Algiz rune turned upside down, from about the 7th century. This phoneme eventually became indistinguishable from the regular r sound in the later stages of Old Norse, at about the 11th or 12th century.

The Yr rune ᛦ is a rune of the Younger Futhark. Its common transliteration is a small capital ʀ. The shape of the Yr rune in the Younger Futhark is the inverted shape of the Elder Futhark rune (ᛉ). Its name yr (“yew”) is taken from the name of the Elder Futhark Eihwaz rune.

In recent Futhark rune Algiz symbolize the man, which ultimately is just an extension of its meaning of “life” is linked elk, deer, an animal very important for the people of Northern Ireland and the Celtic tradition , represents the God Cernunnos, god of fertility and abundance.

Independently, the shape of the Elder Futhark Algiz rune reappears in the Younger Futhark Maðr rune ᛘ, continuing the Elder Futhark ᛗ rune *Mannaz. *Mannaz is the conventional name of the m-rune ᛗ of the Elder Futhark. It is derived from the reconstructed Common Germanic word for “man”, *mannaz.

Younger Futhark ᛘ is maðr (“man”). It took up the shape of the algiz rune ᛉ, replacing Elder Futhark ᛗ. As its sound value and form in the Elder Futhark indicate, it is derived from the letter M (𐌌) in the Old Italic alphabets, ultimately from the Greek letter Mu (μ).

Tyr

Týr is a Germanic god associated with law and heroic glory in Norse mythology, portrayed as one-handed. One handed, Tyr is worshipped as a pinnacle of righteousness, called upon for valor in battle, balance in law, and the fortitude to face the impossible.

As the cloud of war blackens the world, and fear grips the people, Tyr is stooped by the weight of expectation. With blade in hand, he takes the field. For he is Courage, honor, and justice. Tiw was equated with Mars in the interpretatio germanica. Tuesday is “Tīw’s Day” (also in Alemannic Zischtig from zîes tag), translating dies Martis.

Old Norse Týr, literally “god”, plural tívar “gods”, comes from Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz (cf. Old English Tīw, Old High German Zīo), which continues Proto-Indo-European *deiwós “celestial being, god” (cf. Welsh duw, Latin deus, Lithuanian diẽvas, Sanskrit dēvá, Avestan daēvō (false) “god”, Serbo-Croatian div giant). And *deiwós is based in *dei-, *deyā-, *dīdyā-, meaning ‘to shine’.

It is assumed that Tîwaz was overtaken in popularity and in authority by both Odin and Thor at some point during the Migration Age, as Odin shares his role as God of war. Dyēus is believed to have been the chief deity in the religious traditions of the prehistoric Proto-Indo-European societies. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in society.

Although some of the more iconic reflexes of Dyeus are storm deities, such as Zeus and Jupiter, this is thought to be a late development. The deity’s original domain was over the daylight sky, and indeed reflexes emphasise this connection to light: Tiwaz (Stem: Tiwad-) was the Luwian Sun-god.

Tiwas rune

Tiwaz is a warrior rune named after the god Tyr who is the Northern god of law and justice. It is a rune that represents the balance and justice ruled from a higher rationality. It represents the sacrifice of the individual (self) for the well-being of the whole (society).

Honor, justice, leadership and authority. Analysis, rationality. Knowing where one’s true strengths lie. Willingness to self-sacrifice. Victory and success in any competition or in legal matters.

Tiwaz Reversed or Merkstave: One’s energy and creative flow are blocked. Mental paralysis, over-analysis, over-sacrifice, injustice, imbalance. Strife, war, conflict, failure in competition. Dwindling passion, difficulties in communication, and possibly separation.

Mannaz rune

Mannus, according to the Roman writer Tacitus, was a figure in the creation myths of the Germanic tribes. According to Tacitus Mannus was the son of Tuisto and the progenitor of the three Germanic tribes Ingaevones, Herminones and Istvaeones. The names Mannus and Tuisto/Tuisco seem to have some relation to Proto-Germanic Mannaz, “man” and Tiwaz, “Tyr, the god”.

Mannaz represents the fundamental human qualities of all the men and the women: it is the common experience. The archetype of the humans, considered as the reflection of every thing in the existence, is represented by its shape which still evokes by its geometry the idea of the mutual support. Its legs, connected by Gebo’s cross, evoke a stiff shape identical to the stability acquired thanks to the solidarity.

Mannaz is the rune of the accomplished Man. The most positive human qualities are associated with Mannaz, this rune symbolizes the hope in a bigger accomplishment of Humanity and about its best qualities such as the kindness and the generosity. Mannaz also represents the social order necessary to every person to realize his or her human potential.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the god of the sea in classical mythology. In Hindu mythology it is the weapon of Shiva, known as trishula (Sanskrit for “triple-spear”). In Greek, Roman, and Hindu mythology, the trident is said to have the power of control over the ocean.

Neptune

Neptune was the god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. Salacia, the goddess of saltwater, was his wife. As his wife, Salacia bore Neptune three children, the most celebrated being Triton, whose body was half man and half fish. She is identified with the Greek goddess Amphitrite, who is the wife of Poseidon and the queen of the sea.

In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune was the brother of Jupiter and Pluto; the brothers presided over the realms of Heaven, the earthly world, and the Underworld.

Neptune was also considered the legendary progenitor god of a Latin stock, the Faliscans, who called themselves Neptunia proles. In this respect he was the equivalent of Mars, Janus, Saturn and even Jupiter among Latin tribes. Salacia would represent the virile force of Neptune.

Among ancient sources Arnobius provides important information about the theology of Neptune: he writes that according to Nigidius Figulus Neptune was considered one of the Etruscan Penates, together with Apollo, the two deities being credited with bestowing Ilium or Troy situated in the southwest mouth of the Dardanelles strait and northwest of Mount Ida with its immortal walls.

Trident

A trident is a three-pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm. The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the god of the sea in classical mythology. In Hindu mythology it is the weapon of Shiva, known as trishula (Sanskrit for “triple-spear”).

The word “trident” comes from the French word trident, which in turn comes from the Latin word tridens or tridentis: tri “three” and dentes “teeth”. Sanskrit trishula is compound of tri (“three”) + ṣūla (“thorn”). The Greek equivalent is “tríaina”, from Proto-Greek “trianja” (“threefold”).

In Greek, Roman, and Hindu mythology, the trident is said to have the power of control over the ocean. In relation to its fishing origins, the trident is associated with Poseidon, the god of the sea in Greek mythology, and his Roman counterpart Neptune. In Roman myth, Neptune also used a trident to create new bodies of water and cause earthquakes. A good example can be seen in Gian Bernini’s Neptune and Triton.

In Greek myth, Poseidon used his trident to create water sources in Greece and the horse. Poseidon, as well as being god of the sea, was also known as the “Earth Shaker” because when he struck the earth in anger he caused mighty earthquakes and he used his trident to stir up tidal waves, tsunamis and sea storms.

In Hindu legends and stories Shiva, a Hindu God who holds a trident in his hand, uses this sacred weapon to fight off negativity in the form of evil villains. The trident is also said to represent three gunas mentioned in Indian vedic philosophy namely sāttvika, rājasika, and tāmasika. The trishula of the Hindu god Shiva. A weapon of South-East Asian (particularly Thai) depiction of Hanuman, a character of Ramayana.

In religious Taoism, the trident represents the Taoist Trinity, the Three Pure Ones. In Taoist rituals, a trident bell is used to invite the presence of deities and summon spirits, as the trident signifies the highest authority of Heaven.

Paredrae

Salacia is known as the goddess of springs, ruling over the springs of highly mineralized waters. Salacia is represented as a beautiful nymph, crowned with seaweed, either enthroned beside Neptune or driving with him in a pearl shell chariot drawn by dolphins, sea-horses (hippocamps) or other fabulous creatures of the deep, and attended by Tritons and Nereids.

Venilia, in Roman mythology, is a deity associated with the winds and the sea. She and Salacia are the paredrae, entities who pair or accompany a god, of Neptune. According to Virgil and Ovid she was a nymph, the sister of Amata, and the wife of Janus (or Faunus) with whom she had three children, Turnus, Juturna, and Canens.

In the view of Dumézil, Neptune’s two paredrae Salacia and Venilia represent the overpowering and the tranquil aspects of water, both natural and domesticated: Salacia would impersonate the gushing, overbearing waters and Venilia the still or quietly flowing waters. Dumézil’s interpretation has though been varied as he also stated that the jolt implied by Salacia’s name, the attitude to be salax lustful, must underline a feature characteristic of the god.

Salacia and Venilia have been discussed by scholars both ancient and modern. Varro connects the first to salum, sea, and the second to ventus, wind. Festus writes of Salacia that she is the deity that generates the motion of the sea. While Venilia would cause the waves to come to the shore Salacia would cause their retreating towards the high sea.

Mermaid

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including the Near East, Europe, Africa and Asia.

Mermaids are sometimes associated with perilous events such as floods, storms, shipwrecks and drownings. In other folk traditions (or sometimes within the same tradition), they can be benevolent or beneficent, bestowing boons or falling in love with humans.

The word mermaid is a compound of the Old English mere (sea), and maid (a girl or young woman). The male equivalent of the mermaid is the merman, also a familiar figure in folklore and heraldry. Although traditions about and sightings of mermen are less common than those of mermaids, they are generally assumed to co-exist with their female counterparts.

Pisces is the twelfth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans 330° to 360° of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac the sun transits this area on average between February 18 and March 20, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits this area between approximately March 13 and April 13. The symbol of the fish is derived from the ichthyocentaurs, who aided Aphrodite when she was born from the sea.

Virgo is the sixth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans the 150-180th degree of the zodiac. Under the tropical zodiac, the Sun transits this area on average between August 23 and September 22, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits the constellation of Virgo from September 17 to October 17.

The constellation Virgo has multiple different origins depending on which mythology is being studied. The symbol of the maiden is based on Astraea. Pisces has been called the “dying god,” where its sign opposite in the night sky is Virgo, or, the Virgin Mary.

Most myths generally view Virgo as a virgin/maiden with heavy association with wheat. In Greek and Roman mythology they relate the constellation to Demeter, mother of Persephone, or Proserpina in Roman, the goddess of the harvest.

The first stories of mermaids appeared in ancient Assyria c. 1000 BC., in which the goddess Atargatis, the chief goddess of northern Syria in Classical Antiquity, transformed herself into a mermaid out of shame for accidentally killing her human lover.

Primarily Atargatis was a goddess of fertility, but, as the baalat (“mistress”) of her city and people, she was also responsible for their protection and well-being. As Ataratheh, doves and fish were considered sacred to her: doves as an emblem of the Love-Goddess, and fish as symbolic of the fertility and life of the waters.

Atargatis is seen as a continuation of Bronze Age goddesses. At Ugarit, cuneiform tablets attest the three great Canaanite goddesses:ʾAṭirat, described as a fecund “Lady Goddess of the Sea”, who is identified with Asherah, Anat, the war-like virgin goddess, andʿAțtart, the goddess of love.

These shared many traits with each other and may have been worshipped in conjunction or separately during 1500 years of cultural history. Cognates of Ugaritic ʿAțtart include Phoenician ʿAštart – hellenized as Astarte –, Old Testament Hebrew ʿAštoreth, and Himyaritic ʿAthtar. Compare the cognate Akkadian form Ištar.

Asherah in ancient Semitic religion, is a mother goddess who appears in a number of ancient sources. Sources from before 1200 BC almost always credit Athirat with her full title “Lady Athirat of the Sea” or as more fully translated “she who treads on the sea”. The name is understood by various translators and commentators to be from the Ugaritic root ʾaṯr “stride”, cognate with the Hebrew root ʾšr, of the same meaning.

Asherah is identified as the queen consort of the Sumerian god Anu, and Ugaritic El, the oldest deities of their respective pantheons, as well as Yahweh, the god of Israel and Judah. She is equated with the native Egyptian goddess Hathor. Among the Hittites this goddess appears as Asherdu(s) or Asertu(s), the consort of Elkunirsa (“El the Creator of Earth”).

Athirat in Akkadian texts appears as Ashratum (or, Antu), the wife of Anu, the God of Heaven. In contrast, ʿAshtart is believed to be linked to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar who is sometimes portrayed as the daughter of Anu while in Ugaritic myth, ʿAshtart is one of the daughters of El, the West Semitic counterpart of Anu.

Pisces

Neptune is the ruling planet of Pisces and is exalted in Cancer. The Pisces is the twelfth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans 330° to 360° of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac the sun transits this area on average between February 18 and March 20, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits this area between approximately March 13 and April 13. Its glyph is taken directly from Neptune’s trident, symbolizing the curve of spirit being pierced by the cross of matter.

Today, the First Point of Aries, or the vernal equinox, is in the Pisces constellation. Pisces are the mutable water sign of the zodiac. They represent emotion, intuition, imagination, escapism, romance, and impressionism. The astrological symbol shows the two fishes captured by a string, typically by the mouth or the tails. The fish are usually portrayed swimming in opposite directions; this represents the duality within the Piscean nature.

The age of Pisces began c. 1 AD and will end c. 2150 AD. With the story of the birth of Christ coinciding with this date, many Christian symbols for Christ use the astrological symbol for Pisces, the fishes.

The story of the birth of Christ is said to be a result of the spring equinox entering into the Pisces, as the Savior of the World appeared as the Fisher of Men. This parallels the entering into the Age of Pisces. Pisces has been called the “dying god,” where its sign opposite in the night sky is Virgo, or, the Virgin Mary.

Etymology

The etymology of Latin Neptunus is unclear and disputed. The ancient grammarian Varro derived the name from nuptus i.e. “covering” (opertio), with a more or less explicit allusion to the nuptiae, “marriage of Heaven and Earth”.

Among modern scholars Paul Kretschmer proposed a derivation from IE *neptu- “moist substance”. Similarly Raymond Bloch supposed it might be an adjectival form in -no from *nuptu-, meaning “he who is moist”.

Georges Dumézil though remarked words deriving root *nep- are not attested in IE languages other than Vedic and Avestan. He proposed an etymology that brings together Neptunus with Vedic and Avestan theonyms Apam Napat, Apam Napá and Old Irish theonym Nechtan, all meaning descendant of the waters.

By using the comparative approach the Indo-Iranian, Avestan and Irish figures would show common features with the Roman historicised legends about Neptune. Dumézil thence proposed to derive the nouns from IE root *nepot-, “descendant, sister’s son”.

More recently, in his lectures delivered on various occasions in the 1990s, German scholar Hubert Petersmann proposed an etymology from IE rootstem *nebh- related to clouds and fogs, plus suffix -tu denoting an abstract verbal noun, and adjectival suffix -no which refers to the domain of activity of a person or his prerogatives.

IE root *nebh-, having the original meaning of “damp, wet”, has given Sanskrit nábhah, Hittite nepis, Latin nubs, nebula, German Nebel, Slavic nebo etc. The concept would be close to that expressed in the name of Greek god Uranus, derived from IE root *hwórso-, “to water, irrigate” and *hworsó-, “the irrigator”. This etymology would be more in accord with Varro’s.

Nepet is considered a hydronymic toponym of pre Indoeuropean origin widespread in Europe and from an appellative meaning “damp wide valley, plain”, cognate with the pre-Greek word for “wooded valley”.

The god of springs

Neptune was likely associated with fresh water springs before the sea. Like Poseidon, Neptune was worshipped by the Romans also as a god of horses, under the name Neptunus Equester, a patron of horse-racing.

It has been argued that Indo-European people, having no direct knowledge of the sea as they originated from inland areas, reused the theology of a deity originally either chthonic or wielding power over inland freshwaters as the god of the sea.

This feature has been preserved particularly well in the case of Neptune who was definitely a god of springs, lakes and rivers before becoming also a god of the sea, as is testified by the numerous findings of inscriptions mentioning him in the proximity of such locations.

In the earlier times it was the god Portunus or Fortunus who was thanked for naval victories, but Neptune supplanted him in this role by at least the first century BC when Sextus Pompeius called himself “son of Neptune.”

Servius the grammarian also explicitly states Neptune is in charge of all the rivers, springs and waters. He also is the lord of horses because he worked with Minerva to make the chariot.

He may find a parallel in Irish god Nechtan, master of the well from which all the rivers of the world flow out and flow back to. Poseidon on the other hand underwent the process of becoming the main god of the sea at a much earlier time, as is shown in the Iliad.

Fertility deity and divine ancestor

Preller, Fowler, Petersmann and Takács attribute to the theology of Neptune broader significance as a god of universal worldly fertility, particularly relevant to agriculture and human reproduction. Thence they interpret Salacia as personifying lust and Venilia as related to venia, the attitude of ingraciating, attraction, connected with love and desire for reproduction.

Neptune might have been an ancient deity of the cloudy and rainy sky in company with and in opposition to Zeus/Jupiter, god of the clear bright sky. Besides Zeus/Jupiter, (rooted in IE *dei(h) to shine, who originally represented the bright daylight of fine weather sky), the ancient Indo-Europeans venerated a god of heavenly damp or wet as the generator of life.

This fact would be testified by Hittite theonyms nepišaš (D)IŠKURaš or nepišaš (D)Tarhunnaš “the lord of sky wet”, that was revered as the sovereign of Earth and men. Even though over time this function was transferred to Zeus/Jupiter who became also the sovereign of weather, reminiscences of the old function survived in literature.

The indispensability of water for its fertilizing quality and its strict connexion to reproduction is universal knowledge. The sexual and fertility significance of both Salacia and Venilia is implicated on the grounds of the context of the cults of Neptune, of Varro’s interpretation of Salacia as eager for sexual intercourse and of the connexion of Venilia with a nymph or Venus.

Similar to Caelus, he would be the father of all living beings on Earth through the fertilising power of rainwater. This hieros gamos of Neptune and Earth would be reflected in literature. The virile potency of Neptune would be represented by Salacia (derived from salax, salio in its original sense of salacious, lustful, desiring sexual intercourse, covering).

Salacia would then represent the god’s desire for intercourse with Earth, his virile generating potency manifesting itself in rainfall. While Salacia would denote the overcast sky, the other character of the god would be reflected by his other paredra Venilia, representing the clear sky dotted with clouds of good weather.

The theonym Venilia would be rooted in a not attested adjective *venilis, from IE root *ven(h) meaning to love, desire, realised in Sanskrit vánati, vanóti, he loves, Old Island. vinr friend, German Wonne, Latin Venus, venia.

The deity of the cloudy and rainy sky

Developing his understanding of the theonym as rooted in IE *nebh, it has been proposed that the god would be an ancient deity of the cloudy and rainy sky in company with and in opposition to Zeus/Jupiter, god of the clear bright sky. Similar to Caelus, he would be the father of all living beings on Earth through the fertilising power of rainwater.

This hieros gamos of Neptune and Earth would be reflected in literature, e.g. in pater Neptunus. The virile potency of Neptune would be represented by Salacia (derived from salax, salio in its original sense of salacious, lustful, desiring sexual intercourse, covering).

Salacia would then represent the god’s desire for intercourse with Earth, his virile generating potency manifesting itself in rainfall. While Salacia would denote the overcast sky, the other character of the god would be reflected by his other paredra Venilia, representing the clear sky dotted with clouds of good weather.

The theonym Venilia would be rooted in a not attested adjective *venilis, from IE root *ven(h) meaning to love, desire, realised in Sanskrit vánati, vanóti, he loves, Old Island. vinr friend, German Wonne, Latin Venus, venia. Reminiscences of this double aspect of Neptune would be “uterque Neptunus”.

In Petersmann’s conjecture, besides Zeus/Jupiter, (rooted in IE *dei(h) to shine, who originally represented the bright daylight of fine weather sky), the ancient Indo-Europeans venerated a god of heavenly damp or wet as the generator of life. This fact would be testified by Hittite theonyms nepišaš (D)IŠKURaš or nepišaš (D)Tarhunnaš “the lord of sky wet”, that was revered as the sovereign of Earth and men.

Even though over time this function was transferred to Zeus/Jupiter who became also the sovereign of weather, reminiscences of the old function survived in literature. The indispensability of water for its fertilizing quality and its strict connexion to reproduction is universal knowledge.

Hadad, Adad, Haddad (Akkadian) or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Northwest Semitic and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as “Hadda” in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad.

Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called “Pidar”, “Rapiu”, “Baal-Zephon”, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress.

Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus; the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Amun; the Rigvedic god Indra. In Akkadian, Adad is also known as Ramman (“Thunderer”) cognate with Aramaic Rimmon, which was a byname of Hadad. Ramman was formerly incorrectly taken by many scholars to be an independent Assyrian-Babylonian god later identified with the Hadad.

Though originating in northern Mesopotamia, Adad was identified by the same Sumerogram dIM that designated Iškur in the south. His worship became widespread in Mesopotamia after the First Babylonian Dynasty. A text dating from the reign of Ur-Ninurta characterizes Adad/Iškur as both threatening in his stormy rage and generally life-giving and benevolent.

The form Iškur appears in the list of gods found at Shuruppak but was of far less importance, probably partly because storms and rain were scarce in Sumer and agriculture there depended on irrigation instead. The gods Enlil and Ninurta also had storm god features that decreased Iškur’s distinctiveness. He sometimes appears as the assistant or companion of one or the other of the two.

When Enki distributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as “great radiant bull, your name is heaven” and also called son of Anu, lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.

In other texts Adad/Iškur is sometimes son of the moon god Nanna/Sin by Ningal and brother of Utu/Shamash and Inanna/Ishtar. Iškur is also sometimes described as the son of Enlil. The bull was portrayed as Adad/Iškur’s sacred animal starting in the Old Babylonian period (the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE).

Adad/Iškur’s consort (both in early Sumerian and the much later Assyrian texts) was Shala, a goddess of grain, who is also sometimes associated with the god Dagan. She was also called Gubarra in the earliest texts. The fire god Gibil (named Gerra in Akkadian) is sometimes the son of Iškur and Shala.

He is identified with the Anatolian storm-god Teshub, whom the Mitannians designated with the same Sumerogram dIM. Occasionally Adad/Iškur is identified with the god Amurru, the god of the Amorites.

Adad/Iškur presents two aspects in the hymns, incantations, and votive inscriptions. On the one hand he is the god who, through bringing on the rain in due season, causes the land to become fertile, and, on the other hand, the storms that he sends out bring havoc and destruction.

He is pictured on monuments and cylinder seals (sometimes with a horned helmet) with the lightning and the thunderbolt (sometimes in the form of a spear), and in the hymns the sombre aspects of the god on the whole predominate. His association with the sun-god, Shamash, due to the natural combination of the two deities who alternate in the control of nature, leads to imbuing him with some of the traits belonging to a solar deity.

Descriptions of Adad starting in the Kassite period and in the region of Mari emphasize his destructive, stormy character and his role as a fearsome warrior deity, in contrast to Iškur’s more peaceful and pastoral character. Shamash and Adad became in combination the gods of oracles and of divination in general.

In religious texts, Ba‘al/Hadad is the lord of the sky who governs the rain and thus the germination of plants with the power to determine fertility. He is the protector of life and growth to the agricultural people of the region. The absence of Ba‘al causes dry spells, starvation, death, and chaos.

Nechtan

The name could ultimately be derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *nepot- “descendant, sister’s son”, or, alternatively, from nebh- “damp, wet”. Another etymology suggests that Nechtan is derived from Old-Irish necht “clean, pure and white”, with a root -neg “to wash”, from IE neigᵘ̯- “to wash”.

As such, the name would be closely related mythological beings, who were dwelling near wells and springs: English neck (from Anglosaxon nicor), Swedish Näck, German Nixe and Dutch nikker, meaning “river monster, water spirit, crocodile, hippopotamus”, hence Old-Norse nykr “water spirit in the form of a horse”.

In Etruscan mythology, Nethuns was the god of wells, later expanded to all water, including the sea. According to Georges Dumézil the name Nechtan is perhaps cognate with that of the Romano-British god Nodens or the Roman god Neptunus, and the Persian and Vedic gods sharing the name Apam Napat.

In Irish mythology, the Well of Nechtan (also called the Well of Coelrind, Well of Connla, and Well of Segais) is one of a number of Otherworldly wells that are variously depicted as “The Well of Wisdom”, “The Well of Knowledge” and the source of some of the rivers of Ireland. The well is the home to the salmon of wisdom, and surrounded with hazel trees, which also signify knowledge and wisdom.

Nechtan or Nectan became a common Celtic name and a number of historical or legendary figures bear it. Nechtan was a frequent name for Pictish kings.

In Norse mythology, Mímisbrunnr (Old Norse “Mímir’s well”) is a well associated with the being Mímir, located beneath the world tree Yggdrasil. The well contains “wisdom and intelligence” and “the master of the well is called Mimir.

Mimir is full of learning because he drinks of the well from the horn Giallarhorn (Old Norse “yelling horn” or “the loud sounding horn”), a horn associated with the god Heimdallr and the wise being Mímir. Using Gjallarhorn, Heimdallr drinks from the well and thus is himself wise.

Urðarbrunnr (Old Norse “Well of Urðr”; either referring to a Germanic concept of fate—urðr—or the norn named Urðr) is a well in Norse mythology. Urðarbrunnr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

In both sources, the well lies beneath the world tree Yggdrasil, and is associated with a trio of norns (Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld). In the Prose Edda, Urðarbrunnr is cited as one of three wells existing beneath three roots of Yggdrasil that reach into three distant, different lands; the other two wells being Hvergelmir, located beneath a root in Niflheim, and Mímisbrunnr, located beneath a root near the home of the frost jötnar.

In the Poetic Edda, Urðarbrunnr is mentioned in stanzas 19 and 20 of the poem Völuspá, and stanza 111 of the poem Hávamál. In stanza 19 of Völuspá, Urðarbrunnr is described as being located beneath Yggdrasil, and that Yggdrasil, an ever-green ash-tree, is covered with white mud or loam.

Stanza 20 describes that three norns (Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld) “come from” the well, here described as a “lake”, and that this trio of norns then “set down laws, they chose lives, for the sons of men the fates of men.”

Apzu

The name “Nethuns” is likely cognate with that of the Celtic god Nechtan and the Persian and Vedic gods sharing the name Apam Napat, perhaps all based on the Proto-Indo-European word *népōts “nephew, grandson.” In the Rig Veda, Apām Napāt (Lord Varuna) is the angel of rain. Apam Napat created all existential beings.

Apām Napāt in Sanskrit mean “son of waters” and grandson of Apah and Apąm Napāt in Avestan means “Fire on Water”. Sanskrit and Avestan napāt (“grandson”) are cognate to Latin nepōs and English nephew, but the name Apām Napāt has also been compared to Etruscan Nethuns and Celtic Nechtan and Roman Neptune. Apam Napat has a golden splendour and is said to be kindled by the cosmic waters.

The Abzu or Apsu (ZU.AB; Sumerian: abzu; Akkadian: apsû), also called engur (Sumerian: engur; Akkadian: engurru – lit., ab=’water’ zu=’deep’), was the name for fresh water from underground aquifers which was given a religious fertilising quality in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology.